Overall Theme…………………………………………………………………………1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feb-2021-2.Pdf

INSIGHTSIAS SIMPLYFYING IAS EXAM PREPARATION INSIGHTSIAS SIMPLIFYING IAS EXAM PREPARATION February2021 Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCpoccbCX9GEIwaiIe4HLjwA Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/insightsonindia/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/vinaygb Email: [email protected] www.insightsonindia.com 1 INSIGHTS IAS www.insightsonindia.com INSIGHTS IAS [email protected] Table of Contents INSIGHTS into EDITORIAL 3.Can a ‘bad bank’ solve the growing NPA GENERAL STUDIES II 4 crisis? 52 1.Hitting the right notes with the health budget 4 4.Make peace with nature now 57 2.Boosting confidence: On need for efficient 5.The problem of ageing dams 60 use of COVID-19 vaccine stocks 8 6.Troubled mountains: On Uttarakhand 3.A proper transfer policy needed 12 glacier disaster 64 4.Navigating the storm: On the Fifteenth 7.Towards sustainable growth 68 Finance Commission 15 8.New questions: On COVID-19 infecting one- 5.Indian investments and BITs 18 fifth of Indian population 71 6.Belated, but bold: On Nirmala’s 9.Being petroleum-independent 75 disinvestment policy 22 10.The pros and cons of hydrogen as an 7.Collection of DNA samples will lead to alternative fuel 79 misuse 26 11.Why India is opening up the Geo-spatial 8.A normal budget for abnormal times 30 sector 81 9.Water Governance: Challenges and the 12.Disinformation is a cybersecurity threat Way Forward 34 85 10.Why did the Myanmar military stage a 13.Nanophotonics: Hyderabad scientists coup? 39 manipulate tiny crystals 90 GENERAL STUDIES IV 94 GENERAL STUDIES III 44 1.Mahatma Gandhi’s core values should 1.Economic Survey predicts 11% growth in inspire youth today 94 fiscal 2022 44 ESSAYS 100 2.Revise the text of the Budget speech 47 www.insightsonindia.com 2 INSIGHTS IAS www.insightsonindia.com INSIGHTS IAS [email protected] INSIGHTS into EDITORIAL GENERAL STUDIES II 1.Hitting the right notes with the health budget Context: Health care has taken centre stage due to an unfortunate novel coronavirus pandemic that has devastated lives and livelihoods across the globe. -

India: Airport Security Screening for Passengers Departing on International Flights Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 14 April 2009 IND103120.E India: Airport security screening for passengers departing on international flights Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa In 27 April 2009 correspondence, the Security Manager of Air India in Toronto stated the following in regard to airport security screening for passengers departing on international flights: … when the passenger approaches the check-in counter, his/her travel documents, such as passport, visa, ticket, etc. are checked by an airline check-in agent to verify the genuineness of the [documents] prior to the issuance of a boarding card. After obtaining the boarding card, the passenger goes through immigration checks where his/her passport/visa is thoroughly screened and their biographical data are stored into the computer by the government immigration officials. And, at this stage the passenger's data is matched with the suspected criminal databank. The Security Manager also stated that these screening procedures are generally similar at all airports (27 April 2009). The Bengaluru International Airport [Bangalore] website has a "security and passport control" section for international flight passengers that states that passengers, after acquiring their boarding pass, must proceed to the emigration check area where they are to complete "Visa formalities," after which they can proceed to the "international security control area," and then to the departure area (n.d.). Specific information on the security screening procedures within the emigration check area or the international security control area is not available on this airport website. -

Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure Under Threat of Audit∗

Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit∗ Thomas P. Lyon†and John W. Maxwell‡ May 23, 2007 Abstract We present an economic model of greenwash, in which a firm strategi- cally discloses environmental information and a non-governmental organi- zation (NGO) may audit and penalize the firm for failing to fully disclose its environmental impacts. We show that disclosures increase when the likelihood of good environmental performance is lower. Firms with in- termediate levels of environmental performance are more likely to engage in greenwash. Under certain conditions, NGO punishment of greenwash induces the firm to become less rather than more forthcoming about its environmental performance. We also show that complementarities with NGO auditing may justify public policies encouraging firms to adopt en- vironmental management systems. 1Introduction The most notable environmental trend in recent years has been the shift away from traditional regulation and towards voluntary programs by government and industry. Thousands of firms participate in the Environmental Protec- tion Agency’s partnership programs, and many others participate in industry- led environmental programs such as those of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the Chicago Climate Exchange, and the American Chemistry Council’s “Responsible Care” program.1 However, there is growing scholarly concern that these programs fail to deliver meaningful environmental ∗We would like to thank Mike Baye, Rick Harbaugh, Charlie Kolstad, John Morgan, Michael Rauh, and participants in seminars at the American Economic Association meetings, Canadian Resource and Environmental Economics meetings, Dartmouth, Indiana University, Northwestern, UC Berkeley, UC Santa Barbara and University of Florida for their helpful comments. -

Campaigners' Guide to Financial Markets

The Campaigners’ Guide to Financial Markets THETHE CAMPCAMPAIGNERS’AIGNERS’ GUIDEGUIDE TTOO FINFINANCIALANCIAL MARKETSMARKETS Effff ective Lobbying of Companies and Financial Institutions Nicholas Hildyard Mark Mansley 1 The Campaigners’ Guide to Financial Markets 2 The Campaigners’ Guide to Financial Markets Contents Preface – 7 Acknowledgements – 9 1. FINANCIAL MARKETS - A NEW POLITICAL SPACE – 11 A world transformed – 12 The impacts of globalisation – 14 The growing power of the private sector – 16 The shifting space for change – 17 Lobbying the markets – 18 The power of the market – Markets as “neutral ground” – NGO strengths: market weaknesses – Increasing consumer awareness – Globalisation and increased corporate vulnerability – The rise of ethical shareholding – Changing institutional cultures – New regulatory measures – A willingness to change? The limits of market activism – 33 Is a financial campaign appropriate? – 33 Boxes The increasing economic power of the private sector – 13 What are financial markets? – 14 Changing the framework: From Seattle to Prague – 18 Project finance – 20 Consumer and shareholder activism – 23 A bank besieged: Consumer power against bigotry – 25 Huntingdon Life Sciences: Naming and shaming – 27 First do no harm – 30 The impact of shareholder activism – the US experience (by Michelle Chan-Fishel) – 33 Put your own house in order – 34 Internal review – 33 2. UNDERSTANDING THE MARKETS – PSYCHOLOGY,,, ARGUMENTS AND OPENINGS – 37 Using the mentality of the market to your advantage – 38 Exposing the risks – 39 Key pressure points and how to use them – 41 Management quality – Business strategy – Financial risk: company analysis / project analysis – Non–financial risks – Political risks – Legal risks – Environmental risks – Reputational risks Matching the pressure points to the financial player – 54 Boxes Reading the balance sheet – 40 ABB – Moving out of dams – 43 Three Gorges: Bond issues challenged – 47 3. -

Study on Airport Ownership and Management and the Ground Handling Market in Selected Non-European Union (EU) Countries

Study on airport DG MOVE, European ownership and Commission management and the ground handling market in selected non-EU countries Final Report Our ref: 22907301 June 2016 Client ref: MOVE/E1/SER/2015- 247-3 Study on airport DG MOVE, European ownership and Commission management and the ground handling market in selected non-EU countries Final Report Our ref: 22907301 June 2016 Client ref: MOVE/E1/SER/2015- 247-3 Prepared by: Prepared for: Steer Davies Gleave DG MOVE, European Commission 28-32 Upper Ground DM 28 - 0/110 London SE1 9PD Avenue de Bourget, 1 B-1049 Brussels (Evere) Belgium +44 20 7910 5000 www.steerdaviesgleave.com Steer Davies Gleave has prepared this material for DG MOVE, European Commission. This material may only be used within the context and scope for which Steer Davies Gleave has prepared it and may not be relied upon in part or whole by any third party or be used for any other purpose. Any person choosing to use any part of this material without the express and written permission of Steer Davies Gleave shall be deemed to confirm their agreement to indemnify Steer Davies Gleave for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Steer Davies Gleave has prepared this material using professional practices and procedures using information available to it at the time and as such any new information could alter the validity of the results and conclusions made. The information and views set out in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Commission. -

Environmental Protection in the Information Age

ARTICLES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION IN THE INFORMATION AGE DANIEL C. ESTy* Information gaps and uncertaintieslie at the heart of many persistentpollution and natural resource management problems. This article develops a taxonomy of these gaps and argues that the emerging technologies of the Information Age will create new gap-filling options and thus expand the range of environmental protection strategies. Remote sensing technologies, modern telecommunications systems, the Internet, and computers all promise to make it much easier to identify harms, track pollution flows and resource consumption, and measure the resulting impacts. These developments will make possible a new structure of institutionalresponses to environmental problems including a more robust market in environmental prop- erty rights, expanded use of economic incentives and market-based regulatorystrat- egies, improved command-and-control regulation, and redefined social norms of environmental stewardship. Likewise, the degree to which policies are designed to promote information generation will determine whether and how quickly new insti- tutional approaches emerge. While some potential downsides to Information Age environmental protection remain, the promise of a more refined, individually tai- lored, and precise approach to pollution control and natural resourcemanagement looks to be significant. INTRODUCTION ................................................. 117 I. DEFINING THE ROLE OF INFORMATION IN THE ENVIRONMENTAL REALM ............................... 121 A. Information -

Csr Statements: Incentives and Enforcement in the Wake of the Business Roundtable’S Statement on Corporate Purpose

CSR STATEMENTS: INCENTIVES AND ENFORCEMENT IN THE WAKE OF THE BUSINESS ROUNDTABLE’S STATEMENT ON CORPORATE PURPOSE Arielle Sigel* ABSTRACT Corporate social responsibility (“CSR”) statements—voluntary statements made by a corporation to improve its practices in three broad areas: environmental, social, and governance (“ESG”)—are increasingly expected from companies. Both consumers and investors are interested in whether companies are making efforts at social responsibility. In 2019, the Business Roundtable’s statement focused on CSR, emphasizing corporations’ commitment to stakeholders as well as shareholders. This statement signaled a broader shift away from for-profit companies’ profitability focus, and other prominent industry figures, such as BlackRock’s Larry Fink, continue to voice similar sentiments. The business judgment rule and related corporate law doctrines and cases, such as Dodge v. Ford, provide directors with a great deal of deference—within limits, of course—to make decisions that do not fulfill their primary duty of profit maximization. While CSR statements help companies by providing brand recognition, meeting consumer demand, and creating social good, these companies’ decisions to pursue CSR goals do not always align directly with maximizing profits. This creates a rift between directors’ and companies’ legal obligations and the trend of CSR and stakeholder theory. This Note seeks to close this rift by exploring the incentives behind CSR statements and explaining how directors can fulfill their duties by linking CSR statements to profits. In doing so, it concludes that CSR is a proper corporate purpose. CSR statements, with certain conditions placed on them, benefit both companies and society. If companies get to reap the reputational and financial benefits from making CSR statements, then companies must make good faith efforts to achieve their stated goals. -

Objectives, Features and Impacts New Economic Policy of India Was Launched in the Year 1991 Under the Leadership of P

UNIT IV INDUSTRIAL POLICY SINCE 1991 New Economic Policy of 1991: Objectives, Features and Impacts New Economic Policy of India was launched in the year 1991 under the leadership of P. V. Narasimha Rao. This policy opened the door of the India Economy for the global exposure for the first time. In this New Economic Policy P. V. Narasimha Rao government reduced the import duties, opened reserved sector for the private players, and devalued the Indian currency to increase the export. This is also known as the LPG Model of growth. (Liberalization, Privatisation and Globalisation). New Economic Policy refers to economic liberalisation or relaxation in the import tariffs, deregulation of markets or opening the markets for private and foreign players, and reduction of taxes to expand the economic wings of the country. Manmohan Singh is considered to be the father of New Economic Policy (NEP) of India. Manmohan Singh introduced the NEP on July 24, 1991. The main objectives behind the launching of the New Economic policy (NEP) in 1991 by the union Finance Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh are stated as follows: a. The main objective was to plunge Indian Economy in to the arena of ‘Globalization and to give it a new thrust on market orientation. b. The NEP intended to bring down the rate of inflation. c. It intended to move towards higher economic growth rate and to build sufficient foreign exchange reserves. d. It wanted to achieve economic stabilization and to convert the economy into a market economy by removing all kinds of un-necessary restrictions. e. -

Greenwash + 10 the UN's Global Compact, Corporate Accountability

GreenwashGreenwash ++ 1010 The UN’s Global Compact, Corporate Accountability and the Johannesburg Earth Summit January 2002 Greenwash + 10 The UN’s Global Compact, Corporate Accountability and the Johannesburg Earth Summit Table of Contents Executive Summary and Recommendations........................................1 The Road from Rio..............................................................................2 Global Compact: Theory and Reality ..................................................2 Greenwash and Bluewash Definitions ................................................3 The Global Compact’s Contradictions ................................................4 Bluewash ............................................................................................6 Abstracts of Six Studies of Global Compact Violations........................7 The Business Action for Sustainable Development..............................9 Deep Greenwash ................................................................................9 Shell’s Greenwash—Responsibility without Accountability ..............10 Classic Greenwash ............................................................................10 Shell’s Greenwash Award ..................................................................11 Toward Corporate Accountability—A Framework Convention ........12 The More Things Change..................................................................13 Text of Letter to Secretary General Kofi Annan ................................14 Notes ..........................................................................................15-16 -

'Airports Authority of India (Aai)' Committee on Public

1 'AIRPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA (AAI)' MINISTRY OF CIVIL AVIATION COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC UNDERTAKINGS (2020-21) FIRST REPORT (SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA) LOK SABHA SERCRTARIAT NEW DELHI FIRST REPORT COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC UNDERTAKINGS (2020-21) (SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA) AIRPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CIVIL AVIATION Presented to Lok Sabha on 29.01.2021 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 29.01.2021 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI January, 2021/ Magha, 1942 (Saka ) ii CONTENTS Page (i) COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (2020-21) (vi) (ii) COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (2019-20) (vii) (iii) INTRODUCTION (viii) (iv) ACRONYMS (ix) REPORT PART-I Chapter-I Introduction (i) Brief history of Indian Aviation 1 (ii) Airport Authority of India 1 (iii) Board of Directors 2 (iv) Organization structure 3 (v) Agencies operating at airports 3 (vi) Memorandum of Understanding 4 Chapter-II Physical Performance of AAI 5 (i) Airports managed by AAI 5 (ii) Volume of Air Traffic at Airports 6 (iii) Future Growth in Air Traffic 7 (iv) Cargo growth 9 (v) Creation of Civil Aviation infrastructure 10 (vi) Runway expansion project at Udaipur Airport 11 Chapter-III Financial Performance 12 (i) Revenue from Aeronautical and Non-Aeronautical Services 12 and Other Sources (ii) Profit and Loss Account 13 (iii) Joint Ventures – DIAL and MIAL 17 (iv) Measures taken to improve the functions and profitability 26 Chapter-IV Organisational Matters 28 (i) Granting of Navratna Status to AAI 28 (ii) Human Resource Management 31 (iii) Pilots training facilities 33 (iv) ATC Training facilities 34 (v) -

Annual Report of AAI 2017-18

Hkkjrh; foekuiÙku izkf/dj.k AIRPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA rd Annual Report 23 2 0 1 7 - 1 8 Hon'ble Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi flagging off the first UDAN Flight under Regional Connectivity Scheme (RCS) on Shimla - Delhi sector at Jubbarhati, Shimla Airport. Shri Suresh Prabhu, Union Minister of Civil Aviation, addressing the "Civil Aviation Research Organisation" (CARO) event at Hyderabad C O N T E N T S Highlights 2017-18 02 About AAI 08 General Information 10 Brief Profile of Board Members, Chief Vigilance Officer and KMP 11 Board's Report 14 Corporate Governance Report 23 Management Discussion & Analysis (MD&A) 27 Annexure 3 to Board's Report 52 Annual Report on CSR Activities 57 Sustainability Report 67 Financial Statements of AAI & Auditor's Report thereon 70 Financial Statements of CHIAL & Auditor's Report thereon 110 Financial Statements of AAICLAS Company Ltd. & Auditor's Report thereon 148 Surat Airport Hkkjrh; foekuiÙku izkf/dj.k AIRPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA Signing of MoU between AAI and the French Civil Aviation Authority to further the active technical cooperation programme between India and France. S T Signing of MoU H between AAI and G I Uttarakhand Civil Aviation L Development Authority for the Development of H Aviation Sector G in Uttarakhand. I H Signing of MoU between AAI and Honeywell technology Solutions Lab Pvt. Ltd. in the field of aviation technologies, systems and procedures. 02 23rd Annual Report 2017-18 Hkkjrh; foekuiÙku izkf/dj.k AIRPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA Signing of MoU between AAI and Government of Haryana for development of civil aviation infrastructure in the State. -

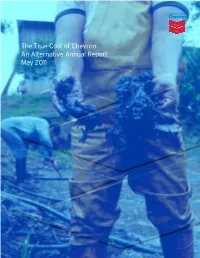

The True Cost of Chevron an Alternative Annual Report May 2011 the True Cost of Chevron: an Alternative Annual Report May 2011

The True Cost of Chevron An Alternative Annual Report May 2011 The True Cost of Chevron: An Alternative Annual Report May 2011 Introduction . 1 III . Around the World . 23 I . Chevron Corporate, Political and Economic Overview . 2. Angola . 23. Elias Mateus Isaac & Albertina Delgado, Open Society Map of Global Operations and Corporate Basics . .2 Initiative for Southern Africa, Angola The State of Chevron . .3 Australia . 25 Dr . Jill StJohn, The Wilderness Society of Western Australia; Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange Teri Shore, Turtle Island Restoration Project Chevron Banks on a Profitable Political Agenda . .4 Burma (Myanmar) . .27 Tyson Slocum, Public Citizen Naing Htoo, Paul Donowitz, Matthew Smith & Marra Silencing Local Communities, Disenfranchising Shareholders . .5 Guttenplan, EarthRights International Paul Donowitz, EarthRights International Canada . 29 Resisting Transparency: An Industry Leader . 6. Chevron in Alberta . 29 Isabel Munilla, Publish What You Pay United States; Eriel Tchwkwie Deranger & Brant Olson, Rainforest Paul Donowitz, EarthRights International Action Network Chevron’s Ever-Declining Alternative Energy Commitment . .7 Chevron in the Beaufort Sea . 31 Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange Andrea Harden-Donahue, Council of Canadians China . .32 II . The United States . 8 Wen Bo, Pacific Environment Colombia . 34 Chevron’s U .S . Coal Operations . 8. Debora Barros Fince, Organizacion Wayuu Munsurat, Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange with support from Alex Sierra, Global Exchange volunteer Alaska . .9 Ecuador . 36 Bob Shavelson & Tom Evans, Cook Inletkeeper Han Shan, Amazon Watch, with support from California . 11. Ginger Cassady, Rainforest Action Network Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange Indonesia . 39 Richmond Refinery . 13 Pius Ginting, WALHI-Friends of the Earth Indonesia Nile Malloy & Jessica Tovar, Communities for a Better Iraq .