The OECD Guidelines and Other Corporate Responsibility Instruments: a Comparison”, OECD Working Papers on International Investment, 2001/05, OECD Publishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate America, the Sullivan Principles, and the Anti-Apartheid Struggle

Black Power in the Boardroom: Corporate America, the Sullivan Principles, and the Anti-Apartheid Struggle JESSICA ANN LEVY This article traces the history of General Motors’ first black director, Leon Sullivan, and his involvement with the Sullivan Principles, a corporate code of conduct for U.S. companies doing business in Apartheid South Africa. Building on and furthering the postwar civil rights and anti-colonial struggles, the international anti-apartheid movement brought together students, union workers, and religious leaders in an effort to draw attention to the horrors of Apartheid in South Africa. Whereas many left-leaning activists advocated sanctions and divestment, others, Sullivan among them, helped lead the way in drafting an alternative strategy for American business, one focused on corporate-sponsored black empowerment. Moving beyond both narrow criticisms of Sullivan as a “sellout” and corporate propaganda touting the benefits of the Sullivan Prin- ciples, this work draws on corporate and “movement” records to reveal the complex negotiations between white and black executives as they worked to situate themselves in relation to anti-racist movements in the Unites States and South Africa. In doing so, it furthermore reveals the links between modern corporate social responsibility and the fight for Black Power within the corporation. © The Author 2019. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Business History Conference. doi:10.1017/eso.2019.32 Published online August 2, 2019 JESSICA ANN LEVY is a postdoctoral research associate in the Department of History and the Corruption Laboratory for Ethics, Accountability, and the Rule of Law (CLEAR) at the University of Virginia. -

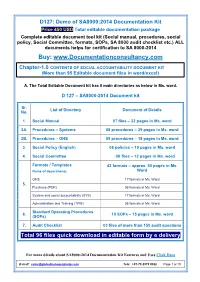

SA 8000:2014 Documents with Manual, Procedures, Audit Checklist

D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Chapter-1.0 CONTENTS OF SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY DOCUMENT KIT (More than 95 Editable document files in word/excel) A. The Total Editable Document kit has 8 main directories as below in Ms. word. D 127 – SA8000-2014 Document kit Sr. List of Directory Document of Details No. 1. Social Manual 07 files – 22 pages in Ms. word 2A. Procedures – Systems 08 procedures – 29 pages in Ms. word 2B. Procedures – OHS 09 procedures – 18 pages in Ms. word 3. Social Policy (English) 08 policies – 10 pages in Ms. word 4. Social Committee 08 files – 12 pages in Ms. word Formats / Templates 43 formats – approx. 50 pages in Ms. Name of departments Word OHS 17 formats in Ms. Word 5. Purchase (PUR) 05 formats in Ms. Word System and social accountability (SYS) 17 formats in Ms. Word Administration and Training (TRG) 05 formats in Ms. Word Standard Operating Procedures 6. 10 SOPs – 15 pages in Ms. word (SOPs) 7. Audit Checklist 03 files of more than 150 audit questions Total 96 files quick download in editable form by e delivery For more détails about SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Features and Uses Click Here E-mail: [email protected] Tele: +91-79-2979 5322 Page 1 of 10 D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Part: B. -

Suggestions from Social Accountability International

Suggestions from Social Accountability International (SAI) on the work agenda of the UN Working Group on Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises Social Accountability International (SAI) is a non-governmental, international, multi-stakeholder organization dedicated to improving workplaces and communities by developing and implementing socially responsible standards. SAI recognizes the value of the UN Working Group’s mandate to promote respect for human rights by business of all sizes, as the implementation of core labour standards in company supply chains is central to SAI’s own work. SAI notes that the UN Working Group emphasizes in its invitation for proposals from relevant actors and stakeholders, the importance it places not only on promoting the Guiding Principles but also and especially on their effective implementation….resulting in improved outcomes . SAI would support this as key and, therefore, has teamed up with the Netherlands-based ICCO (Interchurch Organization for Development) to produce a Handbook on How To Respect Human Rights in the International Supply Chain to assist leading companies in the practical implementation of the Ruggie recommendations. SAI will also be offering classes and training to support use of the Handbook. SAI will target the Handbook not just at companies based in Western economies but also at those in emerging countries such as Brazil and India that have a growing influence on the world’s economy and whose burgeoning base of small and medium companies are moving forward in both readiness, capacity and interest in managing their impact on human rights. SAI has long term relationships working with businesses in India and Brazil, where national companies have earned SA8000 certification and where training has been provided on implementing human rights at work to numerous businesses of all sizes. -

From Corporate Responsibility to Corporate Accountability

Hastings Business Law Journal Volume 16 Number 1 Winter 2020 Article 3 Winter 2020 From Corporate Responsibility to Corporate Accountability Min Yan Daoning Zhang Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_business_law_journal Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Min Yan and Daoning Zhang, From Corporate Responsibility to Corporate Accountability, 16 Hastings Bus. L.J. 43 (2020). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_business_law_journal/vol16/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Business Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 - YAN _ZHANG - V9 - KC - 10.27.19.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 11/15/2019 11:11 AM From Corporate Responsibility to Corporate Accountability Min Yan* and Daoning Zhang** I. INTRODUCTION The concept of corporate responsibility or corporate social responsibility (“CSR”) keeps evolving since it appeared. The emphasis was first placed on business people’s social conscience rather than on the company itself, which was well reflected by Howard Bowen’s landmark book, Social Responsibilities of the Businessman.1 Then CSR was defined as responsibilities to society, which extends beyond economic and legal obligations by corporations.2 Since then, corporate responsibility is thought to begin where the law ends. 3 In other words, the concept of social responsibility largely excludes legal obedience from the concept of social responsibility. An analysis of 37 of the most used definitions of CSR also shows “voluntary” as one of the most common dimensions.4 Put differently, corporate responsibility reflects the belief that corporations have duties beyond generating profits for their shareholders. -

Corporate Governance and Responsibility Foundations of Market Integrity

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Spotlight OECD principles Corporate governance and responsibility Foundations of market integrity Bill Witherell, Head, OECD Directorate for Financial, Fiscal and Enterprise Affairs © Getty Images Good governance goes he recent spate of US corporate investment assessments followed by a sharp beyond common sense. It is failures and breakdowns in truthful market correction that spelt the end for a key part of the contract Taccounting has undermined people’s thousands of high-tech wannabes. Still, it is faith in financial reporting, corporate difficult to disentangle the negative effects that underpins economic leadership, and the integrity of markets the these two parallel developments have had on growth in a market economy world over. The fact that the wave of the confidence of investors. scandals has come hot on the heels of a and public faith in that collapse in the high-tech bubble has a sharp With the bursting of the high-tech bubble, system. The OECD ironic flavour. Both events have their roots in share values were written down and venture Principles of Corporate the heady days of stock market exuberance, capitalists took a bruising, as did many when anything was possible, from creating shareholders. That is the downside of Governance and Guidelines multibillion dollar companies with little committing resources to investments with a for Multinational more than an idea, an investment angel and high risk/high reward profile. But in the cases Enterprises are two a lot of faith, to believing that markets would of corporate misbehaviour, the public, buy any yarn a group of fast-talking employees and pensioners were deliberately essential instruments for executives could spin, even if to cover up misled. -

Regulating Corporations

PROVISIONAL EDITION Regulating Corporations A Resource Guide Désirée Abrahams* Geneva • December 2004 * Désirée Abrahams prepared this report during 2003 and early 2004, when she was a Research Assistant at the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) in Geneva, Switzerland. The author would like to thank Peter Utting, Kate Ives and Anita Tombez for their research and editorial support. The report was prepared under the UNRISD project “Promoting Corporate Social and Environmental Responsibility in Developing Countries: The Potential and Limits of Voluntary Initiatives”, which is partly funded by the MacArthur Foundation. This edition may be subject to minor modifications and copy-editing prior to formal publication. The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) is an autonomous agency engaging in multidisciplinary research on the social dimensions of contemporary problems affecting development. Its work is guided by the conviction that, for effective development policies to be formulated, an understanding of the social and political context is crucial. The Institute attempts to provide governments, development agencies, grassroots organizations and scholars with a better understanding of how development policies and processes of economic, social and environmental change affect different social groups. Working through an extensive network of national research centres, UNRISD aims to promote original research and strengthen research capacity in developing countries. Current research programmes include: Civil Society and Social Movements; Democracy, Governance and Human Rights; Identities, Conflict and Cohesion; Social Policy and Development; and Technology, Business and Society. A list of the Institute’s free and priced publications can be obtained by contacting: UNRISD Reference Centre Palais des Nations 1211 Geneva 10 Switzerland Tel +41 (0)22 917 3020 Fax +41 (0)22 917 0650 [email protected] www.unrisd.org Copyright © United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. -

Corporate Behaviour

CORPORATE BEHAVIOUR Sustainability Focus Report 2016 As a major international company in a controversial sector, we are focused on creating shared value for our business and society, while continuing to work to address the health impacts of our products. A strategic approach to sustainability Our sustainability agenda focuses on the three key areas which have the greatest significance to our business and our stakeholders. Harm Sustainable Corporate Reduction Agriculture and Behaviour We are committed Farmer Livelihoods We are committed to researching, We are committed to operating to the developing and to working to enable highest standards of commercialising less prosperous livelihoods corporate conduct risky alternatives to for all farmers who and transparency. regular cigarettes. supply our tobacco leaf. Performance across all three areas can be found in our annual Sustainability Summary report. In addition, we periodically produce individual focus reports on each area. At the end of 2014, we published two reports covering Harm Reduction and Sustainable Agriculture and Farmer Livelihoods. This 2016 report covers Corporate Behaviour which underpins every area of our business. In this report 02 MARKETING RESPONSIBLY 03 CONTRIBUTING TO COMMUNITIES 04 STRENGTHENING OUR APPROACH TO HUMAN RIGHTS 06 PROMOTING STANDARDS FOR VAPOUR PRODUCTS 08 SAFEGUARDING OUR PEOPLE 09 COLLABORATING TO TACKLE THE ILLEGAL TOBACCO TRADE 10 REDUCING OUR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS 12 UPHOLDING HIGH STANDARDS OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE www.bat.com/sustainability OPERATING TO THE HIGHEST STANDARDS OF CORPORATE CONDUCT Sustainability is one of the key pillars of This is reflected through the many industry-leading our Group strategy and I see it as crucial practices we have in place, such as our approaches to our long-term success. -

The Role of Moral Disengagement in Supply Chain Management Research

http://www.diva-portal.org Postprint This is the accepted version of a paper published in European Business Review. This paper has been peer-reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof-corrections or journal pagination. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Eriksson, D. (2016) The role of moral disengagement in supply chain management research. European Business Review, 28(3): 274-284 https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-05-2015-0047 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:hj:diva-34076 The Role of Moral Disengagement in Supply Chain Management Research Paper Type: Conceptual Structured abstract Purpose: To elucidate the role of moral disengagement in supply chain management (SCM) research, and challenges if the theory is to be used outside of its limitations. Design/methodology/approach: Conceptual paper based on how Bandura has developed and used moral disengagement. Findings: Moral disengagement can be used in SCM research. The theory is not to be applied to the supply chain itself, but SCM can be seen as the environment that is part of a reciprocal exchange that shapes human behavior. Research limitations/implications: The paper suggests a new theory to better understand business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and sustainability in SCM. Further, the paper outlines how the theory should be used, and some challenges that still remain. Practical implications: Originality/value: SCM researchers are given support on how to transfer a theory from psychology to SCM, which could help to progress several areas of the research field. -

Organizational Stakeholders, Management, and Ethics

PAR T I The Organization and Its Environment Organizational Stakeholders, CHAPTER Management, and Ethics 2 Learning Objectives Business and service organizations exist to create valued goods and services that people need or desire. Organizations may have either a profit or nonprofit orientation for the creation of these goods or services. But who decides which particular goods and services an organization should provide, and how do you divide the value that an organization creates among different groups of people such as management, employees, customers, shareholders, and other stakeholders? If people primarily behave self-interestedly, what mecha- nisms or procedures govern the way an organization uses its resources, and what is to stop the different groups within the organization from trying to maximize their own share of the value created, possibly at the detriment or expense of others? At a time when the issue of corporate ethics and management dishonesty and greed has come under intense scrutiny, these questions must be addressed before the issue of design- ing an organization to increase its effectiveness can be investigated. After studying this chapter you should be able to: 1. Identify the various stakeholder groups and their 4. Describe the agency problem that exists in all interests or claims on an organization, its activi- authority relationships and the various mecha- ties, and its created value. nisms, such as the board of directors and 2. Understand the choices and problems inherent stock options, that can be used to align man- in apportioning and distributing the value an agerial behaviour with organizational goals or organization creates. to help control illegal and unethical managerial behaviour. -

Sullivan-Type Principles for U.S. Multinationals in Emerging

"SULLIVAN-TYPE" PRINCIPLES FOR U.S. MULTINATIONALS IN EMERGING ECONOMIES RICHARD T. DE GEORGE* 1. INTRODUCTION The high rate of crime in Russia and the prominence of the Russian Mafia are well known and publicized in the West. President Yeltsin has called crime, which is choking the emerging market economy, Russia's biggest problem.' An article in U.S. News & World Report describes Russia as "a vast bazaar in which the easiest way to get rich is to steal."2 The government has shown itself ineffective in combating crime and in establishing a rule of law. Consequently, many ordinary Russians, who are experiencing a decline in their standard of living,3 are more ambivalent about the march towards capitalism than they were in 1991. Many Western businesses are understandably reluctant to enter an area in which corruption is rampant and the future uncertain. However, the reasons behind the present conditions are too often inadequately understood. As a result, the remedy and the appropriate role of Western companies in the developing market of countries of the former Soviet Union are not clearly * Richard T. De George is University Distinguished Professor of Philosophy, of Russian and East European Studies, and of Business Administration, and Director of the International Center for Ethics in Business at the University of Kansas. His books include The New Marxism; Soviet Ethics and Morality; Business Ethics; and Competing with Integrity in International Business. 1 He has frequently called fighting crime his top priority. See Jack F. Matlock, Russia: The Power of the Mob, NY REVIEW OF BOOKS, July 13, 1995, at 12, 13; see also Julie Corwin et al., The Looting of Russia, U.S. -

Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure Under Threat of Audit∗

Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit∗ Thomas P. Lyon†and John W. Maxwell‡ May 23, 2007 Abstract We present an economic model of greenwash, in which a firm strategi- cally discloses environmental information and a non-governmental organi- zation (NGO) may audit and penalize the firm for failing to fully disclose its environmental impacts. We show that disclosures increase when the likelihood of good environmental performance is lower. Firms with in- termediate levels of environmental performance are more likely to engage in greenwash. Under certain conditions, NGO punishment of greenwash induces the firm to become less rather than more forthcoming about its environmental performance. We also show that complementarities with NGO auditing may justify public policies encouraging firms to adopt en- vironmental management systems. 1Introduction The most notable environmental trend in recent years has been the shift away from traditional regulation and towards voluntary programs by government and industry. Thousands of firms participate in the Environmental Protec- tion Agency’s partnership programs, and many others participate in industry- led environmental programs such as those of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the Chicago Climate Exchange, and the American Chemistry Council’s “Responsible Care” program.1 However, there is growing scholarly concern that these programs fail to deliver meaningful environmental ∗We would like to thank Mike Baye, Rick Harbaugh, Charlie Kolstad, John Morgan, Michael Rauh, and participants in seminars at the American Economic Association meetings, Canadian Resource and Environmental Economics meetings, Dartmouth, Indiana University, Northwestern, UC Berkeley, UC Santa Barbara and University of Florida for their helpful comments. -

Campaigners' Guide to Financial Markets

The Campaigners’ Guide to Financial Markets THETHE CAMPCAMPAIGNERS’AIGNERS’ GUIDEGUIDE TTOO FINFINANCIALANCIAL MARKETSMARKETS Effff ective Lobbying of Companies and Financial Institutions Nicholas Hildyard Mark Mansley 1 The Campaigners’ Guide to Financial Markets 2 The Campaigners’ Guide to Financial Markets Contents Preface – 7 Acknowledgements – 9 1. FINANCIAL MARKETS - A NEW POLITICAL SPACE – 11 A world transformed – 12 The impacts of globalisation – 14 The growing power of the private sector – 16 The shifting space for change – 17 Lobbying the markets – 18 The power of the market – Markets as “neutral ground” – NGO strengths: market weaknesses – Increasing consumer awareness – Globalisation and increased corporate vulnerability – The rise of ethical shareholding – Changing institutional cultures – New regulatory measures – A willingness to change? The limits of market activism – 33 Is a financial campaign appropriate? – 33 Boxes The increasing economic power of the private sector – 13 What are financial markets? – 14 Changing the framework: From Seattle to Prague – 18 Project finance – 20 Consumer and shareholder activism – 23 A bank besieged: Consumer power against bigotry – 25 Huntingdon Life Sciences: Naming and shaming – 27 First do no harm – 30 The impact of shareholder activism – the US experience (by Michelle Chan-Fishel) – 33 Put your own house in order – 34 Internal review – 33 2. UNDERSTANDING THE MARKETS – PSYCHOLOGY,,, ARGUMENTS AND OPENINGS – 37 Using the mentality of the market to your advantage – 38 Exposing the risks – 39 Key pressure points and how to use them – 41 Management quality – Business strategy – Financial risk: company analysis / project analysis – Non–financial risks – Political risks – Legal risks – Environmental risks – Reputational risks Matching the pressure points to the financial player – 54 Boxes Reading the balance sheet – 40 ABB – Moving out of dams – 43 Three Gorges: Bond issues challenged – 47 3.