The Rebuilding of Memory Through Architecture: Case Studies of Leipzig and Dresden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

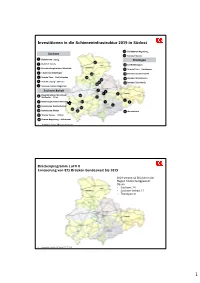

Investitionen in Die Schieneninfrastruktur 2019 in Südost

Investitionen in die Schieneninfrastruktur 2019 in Südost 14 Bahnknoten Magdeburg Sachsen 15 Bahnhof Stendal 1 Bahnknoten Leipzig Thüringen 15 2 Bahnhof Taucha 16 ESTW Meiningen Dresden Hauptbahnhof Mittelhalle 3 17 Strecke Erfurt – Nordhausen 4 Chemnitzer Bahnbogen 14 18 Bahnhof Sondershausen 5 Strecke Pirna – Bad Schandau 13 19 Bahnhof Wernshausen 10 6 Strecke Leipzig – Dresden 12 20 Bahnhof Zella-Mehlis 11 7 Sachsen-Franken-Magistrale 9 Sachsen-Anhalt 2 1 6 Baumaßnahmen Merseburg/ 8 18 Weißenfels – Erfurt 8 3 9 Halle Hauptbahnhof Westseite 17 7 5 4 10 Bahnknoten Dessau/Roßlau 16 19 11 Bahnknoten Köthen 20 21 Werratalbahn 12 Strecke Dessau – Köthen 13 Strecke Magdeburg – Halberstadt 1 Ausgewählte Projekte DB Südost | 21.02.2019 Brückenprogramm LuFV II Erneuerung von 875 Brücken bundesweit bis 2019 2019 werden 44 Brücken in der Region Südost fertiggestellt. Davon • Sachsen: 24 • Sachsen-Anhalt: 12 • Thüringen: 8 2 Ausgewählte Projekte DB Südost | 21.02.2019 1 Bahnknoten Leipzig (1/2) Projektinhalt Ausblick 2019 . Einbindung der Strecken in den Knoten Leipzig von . Fertigstellung und Inbetriebnahme der Zugbildungs- Leipzig Messe bis Leipzig Hauptbahnhof und Behandlungsanlage mit Verbesserung der Anbindung ICE-Werk an den Leipziger Hauptbahnhof . Erneuerung von Brücken im Stadtgebiet Leipzig (Parthe, Rackwitzer Straße, Essener Straße) . Fertigstellung Umbau der Eisenbahnüberführung . Erneuerung der Fernverkehrsbahnsteige 10 bis 15 Essener Straße (teilweise bis auf 410 m Länge) . Erhöhung Ein- und Ausfahrgeschwindigkeit in 2 Gleisen auf 160 km/h zwischen Mockau und . Neuer Haltepunkt Essener Straße Wiederitzsch . Neubau von 14 km Gleis, 80 Weichen, 5,2 km Schallschutzwänden, ca. 50 km Oberleitung . Neubau und Inbetriebnahme eines Elektronischen Stellwerks in Leipzig-Mockau . Neubau der Zugbildungs- und Behandlungsanlage Leipzig-Nord mit verbesserter Anbindung des ICE- Werks an den Leipziger Hauptbahnhof . -

Faktenblatt 5 Jahre S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland Und City-Tunnel

Faktenblatt 5 Jahre S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland und City-Tunnel Leipzig (Leipzig, 13. Dezember 2018) Vor fünf Jahren begann für den Wirtschaftsraum Leipzig/Halle und dessen Umland eine neue Ära des Nahverkehrs: Mit der Fertigstellung des rund vier Kilometer langen Leipziger City-Tunnels nahm am 15. Dezember 2013 die S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland ihren Betrieb auf. Nachdem das Tunnelprojekt am 26. Juni 1996 startete, am 19. Mai 2000 der Planfeststellungsbeschluss vorlag, am 23. Mai 2003 die Bau- und Finanzierungsvereinbarung sowie der Projektvertrag unterzeichnet werden konnten, erfolgte am 9. Juli 2003 der offizielle erste Spatenstich. Nachdem die notwendigen Baufelder freigemacht und im Streckenverlauf zahlreiche Leitungen umverlegt wurden, rollten im Februar 2005 die ersten Bagger an, um beispielsweise das Untergrundmessehaus für die künftige Station Leipzig Markt abzureißen, die Tunneldecke am Vorplatz des Leipziger Hauptbahnhofs zu montieren sowie die Baugrube am Bayerischen Bahnhof auszuheben. Die Verschiebung des Portikus geschah dort am 10. April 2006 unter großer Anteilnahme der Bevölkerung und erregte überregionales Medieninteresse. Auf den Namen „Leonie“ wurde am 11. Januar 2007 die Tunnelbohrmaschine getauft, die sich vom 15. Januar 2007 bis zum 10. März 2008 für die künftige Oströhre durch den Leipziger Untergrund bohrte. Für die Weströhre machte sich „Leonie“ am 9. Mai 2009 wiederum vom Bayerischen Bahnhof auf den Weg zum Leipziger Hauptbahnhof, den sie am 31. Oktober 2009 erreichte. Nun konnte die bahntechnische Ausrüstung des Tunnels mit Gleisen, Weichen, Oberleitung sowie Signal-, Sicherungs- und Brandschutztechnik erfolgen. Auch die vier unterirdischen Stationen Leipzig Hauptbahnhof (tief), Leipzig Markt, Leipzig Wilhelm-Leuschner-Platz und Leipzig Bayerischer Bahnhof wurden entsprechend der Vorgaben der Architekten errichtet und technisch ausgerüstet. -

Folgende Stores Sind Auch Weiterhin Für

FOLGENDE STORES SIND AUCH WEITERHIN FÜR EUCH GEÖFFNET! BERLIN BERLIN BAHNHOF ALEXANDERPLATZ: Mo bis Fr 6:00 - 22:00 Uhr / Sa & So 7:00 - 22:00 Uhr BERLIN BRANDENBURGER TOR: Mo bis So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN BAHNHOF SPANDAU: Mo bis Fr 6:00 - 21:00 Uhr Sa 7:00 - 21:00 Uhr / So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN BAHNHOF FRIEDRICHSTRASSE: Mo bis Fr 6:00 - 21:00 Uhr Sa 7:00 - 21:00 Uhr / So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN GESUNDBRUNNEN CENTER: Mo bis Sa 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr So GESCHLOSSEN BERLIN HAUPTBAHNHOF: Mo bis So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN HERMANNPLATZ: Mo bis Fr 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr Sa 9:00 - 20:00 Uhr / So 10:00 - 20:00 Uhr BERLIN KAISERDAMM: Mo bis Fr 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr Sa 9:00 - 20:00 Uhr / So 10:00 - 20:00 Uhr BERLIN OSTBAHNHOF: Mo bis Fr 7:00 - 21:00 Uhr / Sa & So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN RATHAUSPASSAGEN: Mo bis So 8:00 - 22:00 Uhr BERLIN RING CENTER: Mo bis Sa 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr / So 10:00 - 18:00 Uhr BERLIN SONY CENTER: Mo bis So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN WILMERSDORFER: Mo bis Sa 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr / So 10:00 - 18:00 Uhr BERLIN ZOOM: Mo bis So 7:00 - 22:00 Uhr / Sa & So 8:00 - 22:00 Uhr LEIPZIG LEIPZIG HAUPTBAHNHOF: Mo bis So 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr LEIPZIG NOVA EVENTIS: Mo bis Sa 11:00 - 18:00 Uhr So GESCHLOSSEN LEIPZIG PAUNSDORF: Mo bis So 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr So GESCHLOSSEN 1/5 NRW BOCHUM RHEIN-RUHR PARK: Mo bis Fr 10:00 - 20:00 Uhr Sa 9:00 - 20:00 Uhr So GESCHLOSSEN BONN POSTSTRASSE: Mo bis Sa 7:00 - 22:00 Uhr So 9:00 - 22:00 Uhr DORTMUND HAUPTBAHNHOF: Mo bis Fr 6:00 - 22:00 Uhr Sa & So 8:00 - 22:00 Uhr DORTMUND WESTENHELLWEG: Mo bis So 10:00 - 20:00 Uhr DÜSSELDORF HAUPTBAHNHOF: -

From Aleppo to Dresden with Love Stefan Roch

FROM ALEPPO TO DRESDEN WITH LOVE SEEKING COMPASSION IN A CITY STRUGGLING WITH ITS OWN IDENTITY FEBRUARY 2017 STEFAN ROCH The installation in Dresden (Source: Zeit Online) 1 FROM ALEPPO TO DRESDEN WITH LOVE SEEKING COMPASSION IN A CITY STRUGGLING WITH ITS OWN IDENTITY INTRODUCTION The barricades in Aleppo (Source: The Daily Mail) Three Buses in Dresden One of the most enduring images of the conflict in Aleppo is a photograph of three buses lifted upright to stop government snipers firing on civilians across the frontline. The picture, taken in 2015, shows the barricade that cut a road once connect- ing two central neighborhoods. It was the ultimate symbol of closure. What used to connect people—buses that once took Aleppians from their homes to their jobs—was turned into a towering wall to hold apart two sides committed to nothing less than the extinction of the other. The wall of buses was a haunting image of civil war and the terrible price civilians have paid. For Manaf Halbouni, a German-Syrian artist, the buses represented the desire for dignity, understanding and community that Syrians sought. To remind people of the need for tolerance and discussion, he installed a replica of the barricade in Dresden’s most hallowed public space, the Neumarkt. Aleppo and Dresden, two cities that have become by-words for de- struction and the terrible price of war, are now linked by a challenging and thought-provoking work of art. To those unaware of Dresden’s deeply conflicted identity, it may be surprising that the installation, which Halbouni called Monument, has sparked large-scale protests and opposition. -

Discover Leipzig by Sustainable Transport

WWW.GERMAN-SUSTAINABLE-MOBILITY.DE Discover Leipzig by Sustainable Transport THE SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT GUIDE GERMANY The German Partnership for Sustainable Mobility (GPSM) The German Partnership for Sustainable Mobility (GPSM) serves as a guide for sustainable mobility and green logistics solutions from Germany. As a platform for exchanging knowledge, expertise and experiences, GPSM supports the transformation towards sustainability worldwide. It serves as a network of information from academia, businesses, civil society and associations. The GPSM supports the implementation of sustainable mobility and green logistics solutions in a comprehensive manner. In cooperation with various stakeholders from economic, scientific and societal backgrounds, the broad range of possible concepts, measures and technologies in the transport sector can be explored and prepared for implementation. The GPSM is a reliable and inspiring network that offers access to expert knowledge, as well as networking formats. The GPSM is comprised of more than 140 reputable stakeholders in Germany. The GPSM is part of Germany’s aspiration to be a trailblazer in progressive climate policy, and in follow-up to the Rio+20 process, to lead other international forums on sustainable development as well as in European integration. Integrity and respect are core principles of our partnership values and mission. The transferability of concepts and ideas hinges upon respecting local and regional diversity, skillsets and experien- ces, as well as acknowledging their unique constraints. www.german-sustainable-mobility.de Discover Leipzig by Sustainable Transport Discover Leipzig 3 ABOUT THE AUTHORS: Mathias Merforth Mathias Merforth is a transport economist working for the Transport Policy Advisory Services team at GIZ in Germany since 2013. -

Die Größte Bahnbaustelle Deutschlands Aus- Und Neubaustrecke Nürnberg–Berlin

Die größte Bahnbaustelle Deutschlands Aus- und Neubaustrecke Nürnberg–Berlin Verkehrsprojekt Deutsche Einheit Nr. 8 Nürnberg–Berlin Von der Europäischen Union kofinanziert Einzelne Projekte wurden kofinanziert durch: Operationelles Programm Verkehr EFRE Bund 2007–2013 Transeuropäisches Verkehrsnetz (TEN-V) EUropÄISCHE UNION Bundesministerium für Verkehr und Investition in ihre Zukunft digitale Infrastruktur Europäischer Fonds für regionale Entwicklung Das Ziel 2017: Berlin–München in vier Stunden Fahrzeiten: Schnellzug Berlin–München Bald können Hochgeschwindigkeitszüge auf der gesamten Bahn vor Baubeginn ca. 7:10 neuen Strecke fahren – mit bis zu 300 km/h. Sie bringen Menschen zwischen Berlin und München in Rekordzeiten Bahn 2011 ca. 6:00 von City zu City. Der Zug wird zur echten Alternative zum Auto und Flugzeug. Bahn 2018 ca. 4:00 Das Verkehrsprojekt Deutsche Einheit Nr. 8 (VDE 8), die Auto Verbindung zwischen Nürnberg und Berlin, strebt auf seine komplette Fertigstellung zu. Ende 2015 ist die Neubau Flugzeug* *Vergleich Innenstadt–Innenstadt strecke Erfurt–Leipzig/Halle eröffnet worden, 2017 werden alle neuen Trassen zwischen Nürnberg und Berlin fertig sein. Das ZehnMilliardenProjekt wurde 1991 von der Bundes regierung beschlossen, um die Verkehrsanbindung zwischen Ost und West, zwischen Nord und Süd zu verbessern. Es ist gleichzeitig ein Lückenschluss im deutschen Schnell bahnnetz. Darüber hinaus werden auf der Trasse auch Güterzüge fahren. Die Strecke eröffnet viele Möglichkei ten, hochmoderne Verkehrskonzepte umzusetzen – der Beginn einer neuen Ära des Bahnreisens. Seit Dezember 2015 hat die Inbetriebnahme der Neubau strecke Erfurt–Leipzig/Halle (VDE 8.2) das Tempo im Ost WestVerkehr bereits deutlich erhöht Reisende zwischen Dresden und Frankfurt sind nun eine Stunde schneller am Ziel. -

Investitionsbedarf Für Das Bundesschienenwegenetz Aus

Investitionsbedarf für das Bundes- schienenwegenetz aus Sicht der Nutzer Achte VDV-Maßnahmenliste Ergebnisse der achten Unternehmensbefragung des Verbandes Deutscher Verkehrsunternehmen (VDV) unter Mitarbeit der Bun- desarbeitsgemeinschaft der Aufgabenträger im SPNV (BAG-SPNV) © Patrick Poendl | fotolia Impressum Verband Deutscher Verkehrsunternehmen e. V. (VDV) Kamekestraße 37–39 · 50672 Köln T 0221 57979-0 · F 0221 57979-8000 [email protected] · www.vdv.de Ansprechpartner Steffen Kerth T 0221 57979-172 F 0221 57979-8172 [email protected] Einführung Zum achten Mal in jeweils zweijährigem Abstand hat der Verband Deutscher Verkehrsunterneh- men (VDV) im Spätsommer 2016 die Eisenbahnverkehrsunternehmen sowie – mit Unterstützung der Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft der Aufgabenträger im SPNV – die Verbünde und Aufgabenträ- ger nach dem aus ihrer jeweils spezifischen Sicht bestehenden Investitionsbedarf im Bundes- schienenwegenetz befragt. Die Ergebnisse bieten wie in den Vorjahren einen konkreten Über- blick über die aus Sicht der Nutzer der Schienenwege bestehenden Probleme sowie über die da- rauf bezogenen investiven Lösungsvorschläge. Die VDV-Maßnahmenliste hat sich in den vergangenen Jahren immer mehr zu einem Erfolgsmo- dell für alle Beteiligten entwickelt. Für die Nutzer, weil ihnen ein Instrument geboten wird, das dabei hilft, die infrastrukturell bedingten Restriktionen im Netz genau dort – namentlich bei der DB Netz AG und beim Bund – zu adressieren, wo die Entscheidungen über die Verwendung der verfügbaren Investitionsmittel getroffen werden. Für die DB Netz AG, weil sie sehr konkrete In- formationen über die Bedürfnisse des Marktes und dessen Vorstellungen zur Beseitigung von Schwachstellen und zur Weiterentwicklung des Netzes erhält. Für den Bund, weil er als wesentli- cher Financier der Eisenbahninfrastruktur erfährt, ob die Strukturen der öffentlichen Netzfinan- zierung – Finanzierungsinstrumente, Mittelverwendung, Finanzierungslinie – den Anforderun- gen der Eisenbahnen und ihrer Kunden und damit auch seinen eigenen verkehrspolitischen Ziel- setzungen gerecht werden. -

Dresden Guide Activities Activities

DRESDEN GUIDE ACTIVITIES ACTIVITIES Dresden Frauenkirche / Dresdner Frauenkirche New Market / Neumarkt A E The trademark sight of Dresden. This impressive church was re-opened A tribute to human persistence. The area was wiped out during World War only a few years ago after being destroyed during World War II firebomb- II, than re-built in socialist realist style. Only some 20 years ago was the ing. square restored to its pre-war look. An der Frauenkirche 5, 01067 Dresden, Germany Neumarkt, 01067 Dresden, Germany GPS: N51.05197, E13.74160 GPS: N51.05111, E13.74091 Phone: +49 351 656 06 100 Procession of Princes / Fürstenzug F An impressive mural, more than 100 meters long made out of 25,000 Zwinger porcelain tiles depicting the lineage of Saxony princes. A must-see. B The impressive Baroque palace built as a part of a former fort is a Augustusstraße, 01067 Dresden, Germany must-see. It hosts the Old Masters' Gallery among others. GPS: N51.05256, E13.73918 Theaterplatz 1, 01067 Dresden, Germany GPS: N51.05208, E13.73456 Semper Opera House / Semperoper Phone: G +49 351 4914601 A majestic opera house boasting a quality ensemble. A must-see for opera fans, but not only them. The building is worth a visit for its sheer beauty. Theaterplatz 2, 01067 Dresden, Germany Dresden Castle / Residenzschloss C GPS: N51.05422, E13.73553 You will find layers upon layers of different architectural styles on this fasci- Phone: nating palace – the former residence of the Saxon kings. +49 351 49110 Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden, Germany GPS: N51.05275, E13.73722 Brühl's Terrace / Brühlsche Terrasse Phone: H +49 351 46676610 A popular promenade located on the bank of Elbe nicknamed the “Balcony of Europe”. -

P0004760 Flyer Knoten Leipzi

Sperrungen im Knoten Leipzig 9. September (22.00 Uhr)– 28. September (18.30 Uhr) Umleitungen Zugausfälle Fahrzeitenänderungen Inhalt 03–05 Einführungstext + Erläuterungen zu den 4 Phasen 06–07 1. Karte; gültig vom 10. Sept., 6.30 Uhr bis 20. Sept., 8 Uhr 08–09 2. Karte; gültig vom 20. Sept., 8 Uhr bis 24. Sept., 8 Uhr 10–11 3. Karte; gültig vom 24. Sept., 8 Uhr bis 28. Sept., 18.30 Uhr 12 Ersatzhaltestellen Lagepläne 14 Lageplan Bad Dürrenberg 15 Lageplan Borsdorf 16 Lageplan Großkorbetha 17 Lageplan Großlehna 18 Lageplan Kötzschau 19 Lageplan Leipzig-Connewitz 20 Lageplan Leipzig/Halle Flughafen 21 Lageplan Leipzig Hbf 22 Lageplan Leipzig-Heiterblick 23 Lageplan Leipzig-Leutzsch 24 Lageplan Leipzig-Liebertwolkwitz 25 Lageplan Leipzig Messe 26 Lageplan Leipzig-Miltitz 27 Lageplan Leipzig Nord 28 Lageplan Leipzig-Paunsdorf 29 Lageplan Leipzig-Rückmarsdorf 30 Lageplan Leipzig-Stötteritz 31 Lageplan Leipzig-Thekla 32 Lageplan Markranstädt 33 Lageplan Rackwitz 34 Lageplan Schkeuditz 35 Lageplan Taucha 36 Impressum 2 24. September (8 Uhr) – 28. September (18.30 Uhr) Von/nach Eilenburg, Torgau, Hoyerswerda: Umleitung ab Leipzig-Heiterblick nach Leipzig-Stötteritz. In Leipzig-Stötteritz werden die Züge der weiter als nach Leipzig Miltitzer Allee geführt. Die Züge in/aus Richtung Wurzen beginnen/enden in Leipzig Hbf oben. Leipzig-Heiterblick – Leipzig Hbf: Ersatzverkehr mit Bus Leipzig-Stötteritz – Leipzig-Paunsdorf: Ersatzverkehr mit Bus Umleitung über Schkeuditz; Ersatzverkehr mit Bus Schkeuditz – Leipzig/Halle Flughafen Ausfall Leipzig/Halle Flughafen – Leipzig-Connewitz; Ersatzverkehr mit Bus Schkeuditz – Leipzig/Halle Flughafen Leipzig Messe – Leipzig Hbf – Leipzig-Stötteritz: Ausfall bis 9. Dezember RE 10 Leipzig Hbf – Taucha: Ersatzverkehr mit Bus Sehr geehrte Reisende, für die schnellen Ein- und Ausfahrten der Züge wurde das Bahnhofsvorfeld des Leipziger Hauptbahnhofes aufwändig umgebaut. -

Folgende Stores Sind Auch Weiterhin Für Euch Geöffnet!

FOLGENDE STORES SIND AUCH WEITERHIN FÜR EUCH GEÖFFNET! BERLIN BERLIN BAHNHOF ALEXANDERPLATZ: Mo bis Fr 6:00 - 22:00 Uhr Sa und So 7:00 - 22:00 Uhr BERLIN BRANDENBURGER TOR: Mo bis So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN BAHNHOF SPANDAU: Mo bis Fr 6:00 - 21:00 Uhr Sa 7:00 - 21:00 Uhr / So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN BAHNHOF FRIEDRICHSTRASSE: Mo bis Fr 6:00 - 21:00 Uhr Sa 7:00 - 21:00 Uhr / So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN GESUNDBRUNNEN CENTER: Mo bis Sa 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr SONNTAG GESCHLOSSEN BERLIN HAUPTBAHNHOF: Mo bis So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN HERMANNPLATZ: Mo bis Fr 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr Sa 9:00 - 20:00 Uhr / So 10:00 - 20:00 Uhr BERLIN KAISERDAMM: Mo bis Fr 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr Sa 9:00 - 20:00 Uhr / So 10:00 - 20:00 Uhr BERLIN OSTBAHNHOF: Mo bis Fr 7:00 - 21:00 Uhr / Sa & So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN RATHAUSPASSAGEN: Mo bis So 8:00 - 22:00 Uhr BERLIN RING CENTER: Mo bis Sa 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr / So 10:00 - 18:00 Uhr BERLIN SONY CENTER: Mo bis So 8:00 - 21:00 Uhr BERLIN WILMERSDORFER: Mo bis Sa 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr / So 10:00 - 18:00 Uhr BERLIN ZOOM: Mo bis So 7:00 - 22:00 Uhr / Sa & So 8:00 - 22:00 Uhr LEIPZIG LEIPZIG HAUPTBAHNHOF: Mo bis So 8:00 - 20:00 Uhr 1/5 NRW BONN POSTSTRASSE: Mo bis Sa 7:00 - 22:00 Uhr So 9:00 - 22:00 Uhr DORTMUND HAUPTBAHNHOF: Mo bis Fr 6:00 - 22:00 Uhr Sa & So 8:00 - 22:00 Uhr DORTMUND WESTENHELLWEG: Mo bis So 10:00 - 20:00 Uhr DÜSSELDORF HAUPTBAHNHOF: Mo bis Fr 6:00 - 22:00 Uhr Sa & So 7:00 - 22:00 Uhr ESSEN HAUPTBAHNHOF: Mo bis Fr 6:00 - 22:00 Uhr Sa & So 7:00 - 22:00 Uhr KÖLN HAUPTBAHNHOF: Mo bis So 7:00 - 22:00 Uhr KÖLN HOHE STRASSE: Mo bis So -

Final Report on Elements of Work Plan

Ref. Ares(2017)3520569 - 12/07/2017 TEN-T Core Network Corridors Scandinavian-Mediterranean Corridor 2nd Phase Final Report on the Elements of the Work Plan Final version: 12.07.2017 12 July 2017 1 Study on Scandinavian-Mediterranean TEN-T Core Network Corridor 2nd Phase (2015-2017) Final Report on the Elements of the Work Plan Information on the current version: The draft final version of the final report on the elements of the Work Plan was submitted to the EC by 22.05.2017 for comment and approval so that a final version could be prepared and submitted by 06.06.2017. That version has been improved with respect to spelling and homogeneity resulting in a version delivered on 30.06.2017. The present version of the report is the final final version submitted on 12.07.2017. Disclaimer The information and views set out in the present Report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for any potential use which may be made of the information contained herein. 12 July 2017 2 Study on Scandinavian-Mediterranean TEN-T Core Network Corridor 2nd Phase (2015-2017) Final Report on the Elements of the Work Plan Table of contents 1 Executive summary ............................................................................... 13 1.1 Characteristics and alignment of the ScanMed Corridor .............................. 13 1.2 Traffic demand and forecast .................................................................. -

Media, Reconstruction, and the Future of Germany's Architectural Past

McFarland: Attack of the Cyberzombies: Media, Reconstruction, and the Future of… Attack of the Cyberzombies: Media, Reconstruction, and the Future of Germany’s Architectural Past TRANSIT vol. 10, no. 2 Rob McFarland Go to any blockbuster film this season, and you are sure to see some city in peril. Supervillains seem to prefer urban settings for their conquests, at least that is where the superheroes always seem to meet them for a final battle. As the ultimate public space, cities serve as the place where we ritually overcome aliens, comets, volcanoes, earthquakes, and many other real or imagined threats to civilization as we know it. And, as the films 28 Days Later, I am Legend, World War Z and countless video games have made clear, there is no place like a city for a zombie invasion, driven by whatever biohazard thrives on high concentrations of humans. Like the superheroes in the megaplex cinemas, contemporary architects have eagerly attacked the latest hypothetical challenge to the carefully engineered urban environment. Since 2010, the “Zombie Safe House Competition” has invited architects to design buildings that keep urban inhabitants safe from lurching, brain-hungry zombies intent on driving humanity to extinction (“N.A.”). Good design is more than a silver bullet: we can avoid monsters and destruction altogether if we put our trust in well-conceived architecture. Architects and architectural critics not only keep us safe from biohazards, but also from other species of walking dead that might arise in the urban landscape. In his 2013 article in Der Spiegel titled “S.P.O.N.—Der Kritiker: Aufstand der Zombies,” Georg Diez warns that zombies are in the process of taking over Berlin.