Downloadable, We Encourage Everyone to Try It Or to Apply It to Their Own University Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

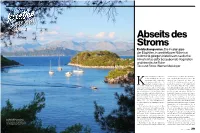

Abseits Des Stroms Entdeckungsreise

KROATIEN SPEZIAL • ELAPHITEN Abseits des Stroms Entdeckungsreise. Die Inselgruppe der Elaphiten, in unmittelbarer Nähe von Dubrovnik gelegen, bietet kaum nautische Infrastruktur, dafür bezaubernde Vegetation und himmlische Ruhe Text und Fotos: Werner Meisinger aee und Kuchen in Korčula. scheidenen Infrastruktur für den Touris- In den Lokalen auf der Fes- mus. Auch für den Bootstourismus. Be- tungsmauer gibt es attraktive scheiden im Vergleich zu dem, was Gelegenheiten dafür. Die Cafés nörd lich der Elaphiten geboten wird. In und Bars sind auf jeden Ge- den Buchten und Häfen Mitteldalmatiens Kschmack eingestellt. Neben der klassischen – von Šolta, Brač, Hvar, Korčula – stecken Cappuccino-Croissant-Palette serviert man die Yachten dicht an dicht, an die Bojen der auch Smoothies und Fruchttörtchen, haus- eigens angelegten Felder werden sie gele- gemachte Säfte und schicke Müslis. Alles gentlich paarweise verordnet. Die Marinas garniert mit Blick aufs Meer. Da bleibt der und Häfen begehren fantastische Gagen Gast im Schatten der Pinien gern eine Zeit für geringste bis gar keine Dienstleis- lang sitzen und beobachtet das Treiben auf tungen. Auch rund Mljet ist noch eine dem Wasser. Während eines solchen Früh- Menge los. Von dort Richtung Osten und stücks kann man mehr Schie vorüber Süden herrscht aber radikale Verkehrsver- gondeln sehen als in den Elaphiten in ei- dünnung. In den Elaphiten gibt es keine ner Woche. Marina und keine bewirtschafteten Bojen. Die Elaphiten sind der südöstliche Fort- Die nächstgelegene Charterbasis ist Dubrov- satz der berühmten Sehnsuchtsdestinati- nik, wo nicht gerade die stärksten Flotten onen vor der kroatischen Küste, zu denen der Bootsverleih-Industrie stationiert sind. es Jahr für Jahr an die vier Millionen Besu- Die Elaphiten liegen also abseits des Stroms, cher zieht. -

Turizam Na Hrvatskim I Njemačkim Otocima

Turizam na hrvatskim i njemačkim otocima Tolj, Andro Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zadar / Sveučilište u Zadru Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:162:985822 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-25 Repository / Repozitorij: University of Zadar Institutional Repository of evaluation works Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za turizam i komunikacijske znanosti Jednopredmetni preddiplomski studij Kulture i turizma Andro Tolj Turizam na hrvatskim i njemačkim otocima Završni rad Zadar, 2016. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za turizam i komunikacijske znanosti Jednopredmetni preddiplomski studij Kulture i turizma Turizam na hrvatskim i njemačkim otocima Završni rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Andro Tolj Mr. sc., Tomislav Krpan Zadar, 2016. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Andro Tolj, ovime izjavljujem da je moj završni rad pod naslovom Turizam na hrvatskim i njemačkim otocima rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga -

Hrvatski Jadranski Otoci, Otočići I Hridi

Hrvatski jadranski otoci, otočići i hridi Sika od Mondefusta, Palagruţa Mjerenja obale istoĉnog Jadrana imaju povijest; svi autori navode prvi cjelovitiji popis otoka kontraadmirala austougarske mornarice Sobieczkog (Pula, 1911.). Glavni suvremeni izvor dugo je bio odliĉni i dosad još uvijek najsustavniji pregled za cijelu jugoslavensku obalu iz godine 1955. [1955].1 Na osnovi istraţivanja skupine autora, koji su ponovo izmjerili opsege i površine hrvatskih otoka i otoĉića većih od 0,01 km2 [2004],2 u Ministarstvu mora, prometa i infrastrukture je zatim 2007. godine objavljena opseţna nova graĊa, koju sad moramo smatrati referentnom [2007].3 No, i taj pregled je manjkav, ponajprije stoga jer je namijenjen specifiĉnom administrativnom korištenju, a ne »statistici«. Drugi problem svih novijih popisa, barem onih objavljenih, jest taj da ne navode sve najmanje otoĉiće i hridi, iako ulaze u konaĉne brojke.4 Brojka 1244, koja je sada najĉešće u optjecaju, uopće nije dokumentirana.5 Osnovni izvor za naš popis je, dakle, [2007], i u graniĉnim primjerima [2004]. U napomenama ispod tablica navedena su odstupanja od tog izvora. U sljedećem koraku pregled je dopunjen podacima iz [1955], opet s obrazloţenjima ispod crte. U trećem koraku ukljuĉeno je još nekoliko dodatnih podataka s obrazloţenjem.6 1 Ante Irić, Razvedenost obale i otoka Jugoslavije. Hidrografski institut JRM, Split, 1955. 2 T. Duplanĉić Leder, T. Ujević, M. Ĉala, Coastline lengths and areas of islands in the Croatian part of the Adriatic sea determined from the topographic maps at the scale of 1:25.000. Geoadria, 9/1, Zadar, 2004. 3 Republika Hrvatska, Ministarstvo mora, prometa i infrastrukture, Drţavni program zaštite i korištenja malih, povremeno nastanjenih i nenastanjenih otoka i okolnog mora (nacrt prijedloga), Zagreb, 30.8.2007.; objavljeno na internetskoj stranici Ministarstva. -

Sustainable Financing Review for Croatia Protected Areas

The World Bank Sustainable Financing Review for Croatia Protected Areas October 2009 www.erm.com Delivering sustainable solutions in a more competitive world The World Bank /PROFOR Sustainable Financing Review for Croatia Protected Areas October 2009 Prepared by: James Spurgeon (ERM Ltd), Nick Marchesi (Pescares), Zrinca Mesic (Oikon) and Lee Thomas (Independent). For and on behalf of Environmental Resources Management Approved by: Eamonn Barrett Signed: Position: Partner Date: 27 October 2009 This report has been prepared by Environmental Resources Management the trading name of Environmental Resources Management Limited, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. Environmental Resources Management Limited Incorporated in the United Kingdom with registration number 1014622 Registered Office: 8 Cavendish Square, London, W1G 0ER CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 AIMS 2 1.3 APPROACH 2 1.4 STRUCTURE OF REPORT 3 1.5 WHAT DO WE MEAN BY SUSTAINABLE FINANCE 3 2 PA FINANCING IN CROATIA 5 2.1 CATEGORIES OF PROTECTED -

Proforma Faktura 5

Razvrstavanje otoka u skupine (Članak 2. Zakona o otocima /Narodne novine N 34/99, 149/99, 32/02, 33/06/) „Otoci se glede demografskog stanja i gospodarske razvijenosti razvrstavaju u dvije skupine. U prvoj skupini su sljedeći otoci i otočići: – nedovoljno razvijeni i nerazvijeni: Unije, Susak, Srakane Vele, Srakane Male, Ilovik, Goli, Sv. Grgur, Premuda, Silba, Olib, Škarda, Ist, Molat, Dugi otok, Zverinac, Sestrunj, Rivanj, Rava, Iž, Ošljak, Babac, Vrgada, Prvić (šibensko otočje), Zlarin, Krapanj, Kaprije, Žirje, Veli i Mali Drvenik, Vis, Biševo, Lastovo, Mljet, Šipan, Lopud, Koločep i Lokrum; – mali, povremeno nastanjeni i nenastanjeni: otočići pred Porečom: Frižital, Perila, Reverol, Sv. Nikola, Veliki Školj; otočići pred Vrsarom: Cavata, Figarolica, Galiner, Galopun, Gusti Školj, Kuvrsada, Lakal, Lunga, Salamun, Sv. Juraj, Školjić, Tovarjež, Tuf; otočići pred Rovinjem: Banjol, Figarola, Figarolica, Gustinja, Kolona, Mala Sestrica, Maškin, Pisulj, Pulari, Sturag, Sv. Katarina, Sv. Andrija, Sv. Ivan, Vela Sestrica, Veštar; brijunski otočići: Galija, Gaz, Grunj, Kotež, Krasnica, Mali Brijun, Pusti, Obljak, Supin, Sv. Jerolim, Sv. Marko, Veli Brijun, Vrsar; otočići pred Pulom: Andrija, Fenoliga, Frašker, Fraškerić, Katarina, Uljanik, Veruda; otočići u medulinskom zaljevu: Bodulaš, Ceja, Fenera, Levan, Levanić, Pomerski školjić, Premanturski školjić, Šekovac, Trumbuja; okolni otočići otoka Cresa: Kormati, Mali Ćutin, Mali Plavnik, Veli Ćutin, Visoki, Zeča; okolni otočići otoka Krka: Galun, Košljun, Plavnik, Prvić, Sv. Marko, Školjić, Zečevo; okolni otočići otoka Lošinja: Karbarus, Koludarc, Kozjak, Male Orjule, Mali Osir, Mišnjak, Murtar, Oruda, Palacol, Samuncel, Sv. Petar, Trasorka, Vele Srakane, Male Srakane, Vele Orjule, Veli Osir, Zabodaski; otočići u Vinodolskom i Velebitskom kanalu te Novigradskom i Karinskom moru: Lisac, Mali Ražanac, Mišjak, Sv. Anton, Sv. -

Matematički Fakultet Biološki Odsjek Problemi

SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU PRIRODOSLOVNO – MATEMATIČKI FAKULTET BIOLOŠKI ODSJEK PROBLEMI ZAŠTITE ZAŠTIĆENIH MORSKIH PODRUČJA U JADRANSKOM MORU PROBLEMS OF PROTECTING THE CONSERVED SEA AREAS IN THE ADRIATIC SEA SEMINARSKI RAD Nikola Malešević Preddiplomski studij biologije (Undergraduate Study of Biology) Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Petar Kružić Zagreb, 2012. Sadržaj 1. Uvod....................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Nacionalni parkovi ................................................................................................................. 3 2.1. Brijuni.................................................................................................................................. 3 2.1.1. Mjere i problemi zaštite.................................................................................................... 4 2.2. Kornati................................................................................................................................. 5 2.2.1 Mjere i problemi zaštite..................................................................................................... 7 2.3. Mljet .................................................................................................................................... 9 2.3.1. Mjere i problemi zaštite.................................................................................................. 10 3. Parkovi prirode.................................................................................................................... -

The Spa and Seaside Resort in the Development of Euro- Mediterranean Travel and Tourism – the Case of Brijuni Islands

THE SPA AND SEASIDE RESORT IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF EURO- MEDITERRANEAN TRAVEL AND TOURISM – THE CASE OF BRIJUNI ISLANDS NATAŠA UROŠEVIĆ | 53 | Juraj Dobrila University of Pula, Croatia The paper will offer a new perspective in elaboration of key phases of the tourism development on the Brijuni Islands, by analysing their important function as an élite Mediterranean spa and seaside resort in a transnational framework. The author will show how cultural practices and patterns of tourist behav- iour, characteristic for European early spa and seaside resorts, spread throughout Mediterranean during the 19th and early 20th century. Similar to an established network of European spas, transnational cultural transfers and common features characterized also a Euro-Mediterranean network of climatic seaside resorts. Many of them developed on the place of an- cient spas and aristocratic residences, such as the first modern élite resorts in Italy and France. We can follow a similar process in the Adriatic, where first climatic spas patronized by royalty attracted a fashionable clientele. The author explored and com- pared some of the well-known island aristocratic residences, such as the Isle of Wight, the Hyėres Islands, Capri, Mallorca, Corfu and Brijuni. The conducted research indicated that the beginnings of modern tourism in the Adriatic followed existing patterns of the European leading spa and seaside resorts. The main contribution of this paper would be in linking revitalisa- tion of unique cultural heritage with a local tourist tradition as a model for sustainable development. Key words: Mediterranean, tourism, European spa, seaside re- sort, Adriatic, Brijuni Volume 13 | 2020 | Number 1 Nataša Urošević INTRODUCTION In the history of European travel and tourism, the Mediterranean has a central position, as a contact zone characterized by intense transnational mobility and intercultural encounters: „It is where the continents of Europe, Africa and Asia meet and where North faces South in an asymmetrical relationship. -

Kartogramski Prikaz Malih, Povremeno Nastanjenih I Nenastanjenih Otoka

DRŽAVNI PROGRAM ZAŠTITE I KORIŠTENJA MALIH, POVREMENO NASTANJENIH I NENASTANJENIH OTOKA I OKOLNOG MORA II PREGLED, POLOŽAJ I RASPORED MALIH, POVREMENO NASTANJENIH I NENASTANJENIH OTOKA I OTOČIĆA 1. ISTARSKA ŽUPANIJA 1.1. Grad Poreč površina opseg naziv MPNNOo vrsta IOO [m2] [m] Altijež “hrid“ 6.271 310 1101 Regata “hrid“ 4.352 279 1102 Sv.Nikola otočić 124.281 2.105 1103 U akvatoriju Grada Poreča nalaze se 3 otoka i/li otočića iz kategorije MPNNOo. Veličinom se izdvaja Sv.Nikola, smješten na zapadnoj strani akvatorija gradske luke Poreča, koji se intenzivno turistički koristi (hotelijerstvo-ugostiteljstvo). U istom akvatoriju je još 6 manjih nadmorskih tvorba (hridi različitog oblika i veličine): Barbaran (2.636m2 ), Butaceja (1.031m2 ), Karbula (1.7.22m2 ), Safarel (1.788 m2 ), Žontuja (2.409 m2 ) i Žontujić (963 m2 ). Kartogram akvatorija: 1:100.000 1.2. Općina Funtana površina opseg naziv MPNNOo vrsta IOO [m2] [m] Gusti Školj mali otočić 12.673 404 1201 Fržital/Frižital mali otočić 16.650 681 1202 Školjić “hrid“ 8.707 369 1203 Tovarjež “hrid“ 7.741 330 1204 Tuf “hrid“ 8.732 387 1205 Veli Školj otočić 59.600 909 1206 U akvatoriju Općine Funtana nalazi se 6 otoka i/li otočića iz kategorije MPNNOo.Veličinom se donekle izdvaja Veli Školj, smješten malo zapadno od Grgetovog rta. U istom akvatoriju su još 3 manje nadmorske Kartogram akvatorija: 1:100.000 tvorbe (hridi različitog oblika i veličine): Bili školj (1.784 m2 ), Orada (1.520 m2 ) i Reverol/Revenol (1.300 m2 ). 1.3. Općina Vrsar površina opseg naziv MPNNOo vrsta IOO [m2] [m] Cavata “hrid“ 8.031 410 1301 Galiner “hrid“ 5.371 264 1302 Lakal “hrid“ 5.123 264 1303 Lunga mali otočić 29.923 826 1304 Kuvrsada/Koversada otočić 67.477 990 1305 Salamun v. -

Studia Honoraria Archaeologica

Studia honoraria archaeologica Zbornik radova u prigodi 65. rođendana prof. dr. sc. Mirjane Sanader Studia honoraria archaeologica Studia ISBN: 978-953-175-809-3 konacan prijedlog korica studia.indd 1 15.2.2021. 12:59:32 Studia honoraria archaeologica Zbornik radova u prigodi 65. rođendana prof. dr. sc. Mirjane Sanader Studia honoraria archaeologica Nakladnik Filozofski fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, Arheološki zavod Odsjeka za arheologiju FF press Za nakladnika Miljenko Šimpraga, o. d. dekana Uredili Domagoj Tončinić Iva Kaić Vinka Matijević Mirna Vukov Recenzenti Bruna Kuntić-Makvić Boris Olujić Ana Pavlović Grafičko oblikovanje i računalni slog Boris Bui, FF press Autor crteža kasnocarske grobnice sa stelama i nalazima iz Vojnića na koricama Krešimir Rončević Autor fotografije prof. dr. sc. M. Sanader Željko Livnjak Tisak Keschoffset, Zagreb-Lučko Naklada 300 kom. Dissertationes et Monographiae 9 Urednik serije: Krešimir Filipec Prihvaćeno na Vijeću Arheološkog zavoda 22. 05. 2019. ISBN 978-953-175-809-3 CIP zapis dostupan je u računalnome katalogu Nacionalne i sveučilišne knjižnice u Zagrebu pod brojem 001085692. Objavljivanje ove knjige financijski su poduprli Ministarstvo znanosti i obrazovanja Republike Hrvatske i Grad Zagreb Studia honoraria archaeologica Zbornik radova u prigodi 65. rođendana prof. dr. sc. Mirjane Sanader Uredili Domagoj Tončinić, Iva Kaić, Vinka Matijević, Mirna Vukov Zagreb, 2020. SADRŽAJ Domagoj TONČINIĆ , Mirjana Sanader i Odsjek za arheologiju Filozofskog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu . 9 Iva KAIĆ, Bibliografija znanstvenih i stručnih radova prof. dr. sc. Mirjane Sanader od 1985. do 2020. godine . .13 Martina BLeČIĆ Kavur & Boris Kavur, Live long and prosper! Rhyta as a symbol of wealth and infinity . 31 Klara BURŠIĆ-MatijAŠIĆ, Toponimi gradine i kašteliri u vremenu i prostoru . -

Brionski Katalog Kamnolomov Katalog Brijunskih

EVROPSKO TERITORIALNO SODELOVANJE EUROPSKA TERITORIJALNA SURADNJA KATALOG BRIJUNSKIH KAMENOLOMA BRIONSKI KATALOG KAMNOLOMOV CATALOGUE OF BRIJUNI QUARRIES Izdavač / Založnik / Published by Javna ustanova Nacionalni park „Brijuni“ Za izdavača / Za založnika / For the publisher Sandro Dujmović Autori / Avtorji / Authors Mira Pavletić Snežana Smolić Lektura / Lektoriranje / Revision Tjaša Kranjec i Alenka Prelec (slovenski jezik) Prijevod / Prevodi / Translation Lena Puhar O’Grady i Paul O’Grady (hrvatski/engleski) Snježana Karinja (hrvatski/slovenski) Fotografije i slikovni prilozi / Fotografijo in slikovni prispevki / Photography and visual material Marko Vrdoljak, Marion Murail, Drago Šoštarić, Fotodokumentacija - NP Brijuni, Zbirka razglednica - NP Brijuni, Zbirka karata – NP Brijuni, Zbirka umjetnina – NP Brijuni Grafičko oblikovanje / Grafično oblikovanje / Graphic design Organizacija d.o.o., Pula Adresa uredništva / Editorial Address Javna ustanova Nacionalni park „Brijuni“, Fažana, Brionska 10 Tisak / Tisk / Printed by Intergrafika, Zagreb Naklada / Izvodi / Print run 500 ISBN 978-953-7264-07-9 Pula, 2015. Ova publikacija nastala je uz pomoć Europske unije. / Ta publikacija je nastala s pomočjo Evropske unije. / This publication was created with the help of the European Union. CIP - Katalogizacija u publikaciji Sveučilišna knjižnica u Puli UDK 622.271.2(497.5)(210.7 Brijuni)(083.82) PAVLETIĆ, Mira Katalog brijunskih kamenoloma = Brionski katalog kamnolomov = Catalogue of Brijuni quarries / <autori, avtorji, authors Mira Pavletić, -

ADRIATIC SEA PILOT Volume II

HRVATSKI HIDROGRAFSKI INSTITUT ADRIATIC SEA PILOT Volume II SUMMARY OF CORRECTIONS APRIL 2020 SUMMARY OF CORRECTIONS Summary of Corrections is an integral part of publication Adriatic Sea Pilot, Volume II (Sedmovraće to Rt Oštra). It includes all corrections in force up to and including NTM 3/2020, and cancels all previous Summaries of Corrections. Authorised distributors should enclose this Summary of Corrections with the above mentioned publication. 2 ADRIATIC SEA PILOT VOLUME II (Sedmovraće to Rt Oštra) 10 - 7/11 IMPORTANT NOTICES AND MARITIME REGULATIONS: Navigation in Kanal Sv. Ante Title NAVIGATION IN KANAL SV. ANTE, Replace by: NAVIGATION IN THE PASSAGE TO ŠIBENIK HARBOUR p. 42 27 - 6/19 IMPORTANT NOTICES AND MARITIME REGULATIONS: NAVIGATION IN THE PASSAGE TO ŠIBENIK HARBOUR, amending Ordinance In the text of Ordinance, amend Channel 71 to Channel 9. p. 42 11 - 7/11 IMPORTANT NOTICES AND MARITIME REGULATIONS, Navigation in Pašmanski Tjesnac: speed For: Vessels over 50 GT, except hydrofoil boats and air-cushion vessels, may transit Pašmanski Tjesnac at a speed not exceeding 10 kn: (...) Read: Ships, yachts or boats may transit Pašmanski Tjesnac at a speed not exceeding 10 kn: (...) p. 43 29 - 3/12 NAVIGATION IN MALI ŽDRELAC PASSAGE: cancellation Entire text entitled NAVIGATION IN MALI ŽDRELAC PASSAGE is cancelled. p. 43 12 - 7/11 IMPORTANT NOTICES AND MARITIME REGULATIONS, Navigation on the Neretva river: draught and length of vessels For: The river is normally navigable by vessels drawing not more than 4.5 m. Read: The river is normally navigable by vessels with a draught not exceeding 4.5 m and a length of up to 80 metres. -

Marine Protection Area ... Now What?!

Marine Protection Area ... Now What?! Yellow buoy - marine protection area Marine Protected Areas ... Meet & Greet with Dolphins ... Now What?! What For? To observe dolphins, the Whale Watcher rules apply to all: A protected area does not mean that the visit is z Established protected areas show that biodiver- prohibited. sity is increasing there. z Approaching dolphins always sideways or from behind—NEVER from the front! On the contrary - but with special attention! z They also have a positive impact on neighbo- In order to protect sensitive habitats and their ring areas, as living beings z Reduce from 300 meters to max. 5-6 kn. inhabitants, there are a variety of rules and measu- tend to migrate to nearby z Keep stable course and a distance of at least 50 rements must be observed. habitats meters to the dolphins. The animals feel safer and stay longer! If you obey them even outside the protected areas z Consider that sustainable we can act positively to protect the entire sea! fisheries can help to ensure z Never cross the path of an individual or never the survival of fish stocks split a group, otherwise they will feel hunted and change their course Please note: and fisheries z If there are other boats in the area, avoid that the z Natural landscapes z Restrictions on cruising, anchoring and stay for remain, dolphins feel surrounded (100m distance at least) sport boats recover and can be explored by interested parties z For mothers and their young keep a distance of z Use of designated buoys in bays with sea grass 100 meters at least z Anchor better on sand and silt, the anchor is z Do not feed—this will affect the natural diet of safer and seagrass meadows are spared dolphins.