Frontiers of Embedded Muslim Communities in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoirs on the History, Folk-Lore, and Distribution of The

' *. 'fftOPE!. , / . PEIHCETGIT \ rstC, juiv 1 THEOLOGICAL iilttTlKV'ki ' • ** ~V ' • Dive , I) S 4-30 Sect; £46 — .v-..2 SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/memoirsonhistory02elli ; MEMOIRS ON THE HISTORY, FOLK-LORE, AND DISTRIBUTION RACESOF THE OF THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES OF INDIA BEING AN AMPLIFIED EDITION OF THE ORIGINAL SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF INDIAN TERMS, BY THE J.ATE SIR HENRY M. ELLIOT, OF THE HON. EAST INDIA COMPANY’S BENGAL CIVIL SEBVICB. EDITED REVISED, AND RE-ARRANGED , BY JOHN BEAMES, M.R.A.S., BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE ; MEMBER OP THE GERMAN ORIENTAL SOCIETY, OP THE ASIATIC SOCIETIES OP PARIS AND BENGAL, AND OF THE PHILOLOGICAL SOCIBTY OP LONDON. IN TWO VOLUMES. YOL. II. LONDON: TRUBNER & CO., 8 and 60, PATERNOSTER ROWV MDCCCLXIX. [.All rights reserved STEPHEN AUSTIN, PRINTER, HERTFORD. ; *> »vv . SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. PART III. REVENUE AND OFFICIAL TERMS. [Under this head are included—1. All words in use in the revenue offices both of the past and present governments 2. Words descriptive of tenures, divisions of crops, fiscal accounts, like 3. and the ; Some articles relating to ancient territorial divisions, whether obsolete or still existing, with one or two geographical notices, which fall more appro- priately under this head than any other. —B.] Abkar, jlLT A distiller, a vendor of spirituous liquors. Abkari, or the tax on spirituous liquors, is noticed in the Glossary. With the initial a unaccented, Abkar means agriculture. Adabandi, The fixing a period for the performance of a contract or pay- ment of instalments. -

5.4 Southern Kingdoms and the Delhi Sultanate

Political Formations UNIT 5 DECCAN KINGDOMS* Structure 5.0 Objectives 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Geographical Setting of the Deccan 5.3 The Four Kingdoms 5.3.1 The Yadavas and the Kakatiyas 5.3.2 The Pandyas and the Hoysalas 5.3.3 Conflict Between the Four Kingdoms 5.4 Southern Kingdoms and the Delhi Sultanate 5.4.1 First Phase: Alauddin Khalji’s Invasion of South 5.4.2 Second Phase 5.5 Administration and Economy 5.5.1 Administration 5.5.2 Economy 5.6 Rise of Independent Kingdoms 5.7 Rise of the Bahmani Power 5.8 Conquest and Consolidation of the Bahmani Power 5.8.1 First Phase: 1347-1422 5.8.2 Second Phase: 1422-1538 5.9 Conflict Between the Afaqis and the Dakhnis and their Relations with the King 5.10 Central and Provincial Administration under the Bahmani Kingdom 5.11 Army Organization under the Bahmani Kingdom 5.12 Economy 5.13 Society and Culture 5.14 Summary 5.15 Keywords 5.16 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 5.17 Suggested Readings 5.18 Instructional Video Recommendations 5.0 OBJECTIVES After going through this Unit, you should be able to: * Prof. Ahmad Raza Khan and Prof. Abha Singh, School of Social Sciences, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi. The present Unit is taken from IGNOU Course 110 EHI-03: India: From 8th to 15th Century, Block 7, Units 26 & 28. • assess the geographical influences on the polity and economy of the Deccan, Deccan Kingdoms • understand the political set-up in South India, • examine the conflicts among the Southern kingdoms, • evaluate the relations of the Southern kingdoms with the Delhi Sultanate, • know their administration and economy, • understand the emergence of new independent kingdoms in the South, • appraise the political formation and its nature in Deccan and South India, • understand the emergence of the Bahmani kingdom, • analyze the conflict between the old Dakhni nobility and the newcomers (the Afaqis) and how it ultimately led to the decline of the Bahmani Sultanate, and • evaluate the administrative structure under the Bahmanis. -

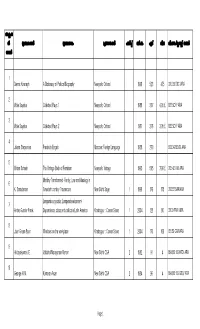

V. Aravindakshan 2.Xlsx

അക്സഷ ന് ഗര്ന്ഥകാരന് ഗര്ന്ഥനാമം പര്സാധകന് പതിപ്പ് വര്ഷംഏട്വിലവിഷയം/കല്ാസ്സ് നമ്പര് നമ്പര് 1 Dennis Kavnagh A Dictionary of Political Biography Newyork: Oxford 1998 523 475 320.092 DIC /ARA 2 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 1 Newyork: Oxford 1988 307 4.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 3 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 2 Newyork: Oxford 1987 276 3.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 4 Jelena Stepanova Frederick Engels Moscow: Foreign Language 1958 270 923.343 ENG/ ARA 5 Miriam Schneir The Vintage Book of Feminism Newyork: Vintage 1995 505 7.99 £ 305.42 VIN/ ARA 6 Matriliny Transformed -Family, Law and Ideology in K. Saradamoni Twenteth century Travancore New Delhi: Sage 1 1999 176 175 306.83 SAR/ARA 7 Lumpenbourgeoisle: Lumpendevelopment- Andre Gunder Frank Dependence, class and politics in Latin America Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 128 80 320.9 FRA/ ARA 8 Joan Green Baun Windows on the workplace Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 170 100 651.59 GRA/ARA 9 Hridayakumari. E. Vallathol Narayanan Menon New Delhi: CSA 2 1982 91 4 894.812 109 HRD/ ARA 10 George. K.M. Kumaran Asan New Delhi: CSA 2 1984 96 4 894.812 109 GEO/ ARA Page 1 11 Tharakan. K.M. M.P. Paul New Delhi: CSA 1 1985 96 4 894.812 109 THA/ ARA 12 335.43 AJI/ARA Ajit Roy Euro-Communism' An Analytical story Calcutta: Pearl 88 10 13 801.951 MAC/ARA Archi Bald Macleish Poetry and Experience Australia: Penguin Books 1960 187 Alien Homage' -Edward Thompson and 14 891.4414 THO/ARA E.P. Thompson Rabindranath Tagore New Delhi : Oxford 2 1998 175 275 15 894.812309 VIS/ARA R.Viswanathan Pottekkatt New Delhi: CSA 1 1998 60 5 16 891.73 CHE/ARA A.P. -

Nimatullahi Sufism and Deccan Bahmani Sultanate

Volume : 4 | Issue : 6 | June 2015 ISSN - 2250-1991 Research Paper Commerce Nimatullahi Sufism and Deccan Bahmani Sultanate Seyed Mohammad Ph.D. in Sufism and Islamic Mysticism University of Religions and Hadi Torabi Denominations, Qom, Iran The presentresearch paper is aimed to determine the relationship between the Nimatullahi Shiite Sufi dervishes and Bahmani Shiite Sultanate of Deccan which undoubtedly is one of the key factors help to explain the spread of Sufism followed by growth of Shi’ism in South India and in Indian sub-continent. This relationship wasmutual andin addition to Sufism, the Bahmani Sultanate has also benefited from it. Furthermore, the researcher made effortto determine and to discuss the influential factors on this relation and its fruitful results. Moreover, a brief reference to the history of Muslims in India which ABSTRACT seems necessary is presented. KEYWORDS Nimatullahi Sufism, Deccan Bahmani Sultanate, Shiite Muslim, India Introduction: are attributable the presence of Iranian Ascetics in Kalkot and Islamic culture has entered in two ways and in different eras Kollam Ports. (Battuta 575) However, one of the major and in the Indian subcontinent. One of them was the gradual ar- important factors that influence the development of Sufism in rival of the Muslims aroundeighth century in the region and the subcontinent was the Shiite rule of Bahmani Sultanate in perhaps the Muslim merchants came from southern and west- Deccan which is discussed briefly in this research paper. ern Coast of Malabar and Cambaya Bay in India who spread Islamic culture in Gujarat and the Deccan regions and they can Discussion: be considered asthe pioneers of this movement. -

Gender Negotiations Among Indians in Trinidad 1917-1947 :I¥

Gender Negotiations among Indians in Trinidad 1917-1947 :I¥ | v. I :'l* ^! [l$|l Yakoob and Zalayhar (Ayoob and Zuleikha Mohammed) Gender Negotiations among Indians in Trinidad 1917-1947 Patricia Mohammed Head and Senior Lecturer Centre for Gender and Development Studies University of the West Indies rit in association with Institute of Social Studies © Institute of Social Studies 2002 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2002 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. Martin's Press LLC Scholarly and Reference Division and Palgrave Publishers Ltd (formerly Macmillan Press Ltd). ISBN 0-333-96278-8 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Cataloguing-in-publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

White Rann – Kalo Dungar Day Tour

Tour Code : AKSR0142 Tour Type : FIT Package 1800 233 9008 MATA NO MADH – WHITE www.akshartours.com RANN – KALO DUNGAR DAY TOUR 0 Nights / 1 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW 1Country 3Cities 1Days 3Activities Accomodation Meal NO ACCOMODATION NO MEALS Highlights Visa & Taxes Accommodation on double sharing Breakfast and dinner at hotel 5 % GST Extra Transfer and sightseeing by pvt vehicle as per program Applicable hotel taxes SIGHTSEEINGS OVERVIEW - Mata no madh - Kalo dungar - White rann SIGHTSEEINGS Kalo Dungar - Dattatreya Temple Kalo Dungar Alias Black Hill Is The Highest Point Of The Kutch Region, Offering The Bird's-Eye View Of The Great Rann Of Kutch. At Only 462 Meters, The Hill Itself Is An Easy Climb And Can Be Reached By Either Hopping In Private Taxi Or Gujarat Tourism Buses. Dattatreya Temple, A 400-Year-Old Shrine Sacred To Lord Dattatreya Is Noticeable On The Top Of The Hill. Many Fables And Tales Are Associated With The History Of The Kalo Dungar, One Of Them Say That Dattatreya, The Three-Headed Incarnation Of Lord Brahma, Lord Vishnu And Lord Shiva In The Same Body, Stopped At This Hill While Walking On The Earth. On The Hills, He Noticed Many Hungry Jackals And Offered Them His Body To Eat. When Jackals Started Eating Dattatreya's Body, His Body Automatically Regenerated. The Practice Of Feeding Jackals Is Still Practiced By The People. Priest Of The Temple Prepares Food And Serve It To Jackals Each Morning And Evening, After The Aarti (Hindu Religious Ritual Of Worship). There Is A Bhojnalaya Too That Brings People From All Walks Of Life To Eat A Meal Together, Free Of Cost. -

A Historical Transition of Banjara Community in India with Special Reference to South India Nagaveni T

Research Journal of Recent Sciences _________________________________________________ ISSN 2277-2502 Vol. 4(ISC-2014), 11-15 (2015) Res. J. Recent. Sci. A Historical Transition of Banjara Community in India with Special Reference to South India Nagaveni T. Department of History, Government First Grade College, Kuvempunagar, Mysore-570 023, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in, www.isca.me Received 13 rd November 2014, revised 9th March 2015, accepted 25 th March 2015 Abstract An incisive insight into the literature on Banjara Community clearly indicates that ample literature has been produced by the Western and Indian scholars. Yet the treatment of the problem is exponential. Deep delve into the process of historical transition of the Banjara Community enables us to focus on various controversial issues and complexities of historical significance. Issues like Semantics, Historicity, Location, Ethnicity, Categorization, Caste-clan, Dichotomy and the community’s identity continued to gravitate the attention of the scholars and researchers alike. Lack of unanimity among the scholars and policy makers on these contentious issues has added perplexity to the puzzle. Ambiguous explanations given by the community historians have further complicated the clear-cut understanding of the process of historical transition. The antiquity of this Banjara Community is traceable to Harappa and Mohenjodaro. Its influence continued to spread and retain its relevance down the centuries to shape and reshape the course of history. There is a speculation about the group of Banjaras who mere concentrated outside India and called as Roma Gypsy, where their social history is not yet clear but proved to be of Indian Origin. This paper however strives to focus on historical transition within the context of India from 13 th Century A.D. -

Dowry Death in Assam: a Sociological Analysis

MSSV JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES VOL. 1 N0. 2 [ISSN 2455-7706] DOWRY DEATH IN ASSAM: A SOCIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS Rubaiya Muzib Alumnus, Department of Sociology Mahapurusha Srimanta Sankaradeva Viswavidyalaya Abstract - Dowry is a transfer of parental property at the marriage of a daughter. The word ‘Dowry’ means the property and money that a bride brings to her husband’s house at the time of her marriage. It is a practice which is widespread in the Indian society. Assam is a state of North East India where different ethnic groups are living together and the problem of dowry is evident in this state. In the last few years’ dowry death is regular news of Assam. The dowry is given as a gift or as compensation. This paper tries to analyze the main societal impacts on ancient Indian society, analyzing the influence of the ancient text of Manu, pre- colonial, post-Aryan, and post-British thought. Through this practice of dowry many women lost their lives and bride burning is becoming a serious issue of Assam. To remove the evil effects of dowry, The Dowry Prohibition Act, in force since 1st July 1961, was passed with the purpose of prohibiting the demanding, giving and taking of dowry. But there are many people who are still unaware about this fact. In considering the evil effects of dowry; this paper is an attempt to study dowry death in Assam. In addition, this paper focuses on the laws related to dowry. This study has been conducted on the basis of secondary sources. The paper continues to analyse the problem of dowry in Assam today, and attempts to measure its current effects and implications on the state and its people. -

Perspectives of Caste Census: Why It Is Needed Today?

Perspectives of Caste Census: Why it is needed today? By Premendra Priyadarshi1 Up to 1931, the Census of India included caste too. This practice was abandoned in 1941 because of protests by the nationalists, and also because it was considered worthless, misleading and a waste of time and energy. Column for religion was continued till 2001 census. Thereafter it was felt to be divisive and abandoned from 2011 census. Yet recently, there have been demands in political establishment for and against the caste census and the Union Government seems to be succumbing to pressures. It is desirable that we examine the perspectives of caste census. Why caste abandoned from census in 1941 The most important reason for abandonment of caste census was the ‗worthlessness‘ of the whole exercise because of inconsistency in caste names, which were not fixed and varied between districts, and with time, high incidence of unreliability of individuals‘ statement about caste etc. The Census Commissioner of India for 1931, J.H. Hutton noted, ―Sorting for caste is really worthless unless nomenclature is sufficiently fixed to render the resulting totals close and reliable approximations. Had caste terminology the stability of religious returns, caste sorting might be worthwhile. With the fluidity of current appellations it is certainly not… 227,000 Ambattans have become 10,000, Navithan, Nai, Nai Brahman, Navutiyan, Pariyari claim about 140,000—all terms unrecorded or untabulated in 1921.‖1 Only explanation for this could be that most of the Ambattans of 1921 changed into some other caste. Similarly, the number of Marathas in Central Provinces and Berar increased from 93,901 in 1911, to 206,144 in 1921.2 This more than 110% increase in number can be explained by the mass mobilization of Kunbis (Kurmi-s) to Marathas during the period. -

Rethinking Majlis' Politics: Pre-1948 Muslim Concerns in Hyderabad State

Rethinking Majlis’ politics: Pre-1948 Muslim concerns in Hyderabad State M. A. Moid and A. Suneetha Anveshi Research Centre for Women’s Studies, Hyderabad In the historiography of Hyderabad State, pre-1948 Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (Majlis) figures as a separatist, communal and fanatical political formation. For the nationalist, Hindu and left politics in this region, Majlis has long stood for the ‘other’, wherein concerns articu- lated by it get discredited. In this article, we argue that there is a need to rethink the Majlis’ political perspective and its articulation of Muslim concerns by placing them in the context of the momentous political developments in the first half of the twentieth century. Caught between the imminent decline of the Asaf Jahi kingdom and the arrival of democratic politics, the Majlis saw the necessity of popular will but also the dangers of majoritarianism during such transitions and fought against the threat of imminent minoritisation of Muslims in the Hyderabad State. This article draws on the Urdu writings on the Majlis and Bahadur Yar Jung’s speeches that have been rarely used in Telugu or English writings on this period. Keywords: Muslim politics in Hyderabad State, Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen, Deccani nationalism, Bahadur Yar Jung, democratic politics in Hyderabad State Introduction Writing the history or discussing the politics of Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (Majlis, hereafter) of the 1940s is beset with problems of perspective that arise out of that very history. Between 1930 and 1948, Hyderabad State underwent complex and rapid changes: a shift in the communal profile of the state, which led to the polarisation of Hindus and Muslims; the transformation of local struggles for civil liberties and political reforms into a nationalist struggle, backed by the Indian army in the border districts from 1947; the peasant revolt against the feudal hierarchy in rural Telangana and its armed struggle against the Nizam’s government; and most Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Gita Ramaswamy, Shefali Jha, R. -

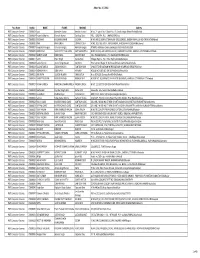

To View the List of Candidates Who Applied Earlier Under Adv No. 2/2014

Advt. No. 2 / 2014 Post Name RegNo NAME FNAME MNAME Address PGT Computer Science 70000003 Jyoti Narender Kumar Neelam Kumari H.No. 21 Ward. No. 6 Barak No. 15 Gandhi Nagar RohtakRohtakRohtak PGT Computer Science 70000004 Priyanka Sharma Ramesh Kumar Sandhya Devi VILL. - DHUKRA, P.O. - JAMALSIRSASirsa PGT Computer Science 70000005 POONAM KRISHAN KUMAR SUSHILA H.NO-248/2, NEAR JOT RAM JAIN GIRLS SCHOOL, BABRA MOHALLA, ROHTAKROHTAKRohtak PGT Computer Science 70000006 AMIT MAN SINGH SOMVATI DEVI H.NO. 109, GALI NO. 4, VIKAS NAGAR, PHOOSGARH ROADKARNALKarnal PGT Computer Science 70000007 meenakshi kangra billu ram kangra kamlesh kangra #734/31 mahadev colony siwan gate kaithalkaithalKaithal PGT Computer Science 70000008 KIRTI RANA SHRI SATYA PAUL RANA SMT SHAKUNTLA RANA NIWAS, #23 SATSANG VIHAR , NEAR EKTA CHOWK, AMBALA CANTTAMBALAAmbala PGT Computer Science 70000010 MANJIT SINGH RAMNIWAS RAJPATI DEVI VILL NAURANGABAD P.O BAMLABHIWANIBhiwani PGT Computer Science 70000011 Sumit Prem Singh Sunita Devi Village- Baghru, P.O.- Tihar BaghruSonipatSonepat PGT Computer Science 70000012 Kavita Kumari Anand Singh Gusain Surji Devi Hno 3,Anand Nagar-'B',Boh road,Ambala CanttambalaAmbala PGT Computer Science 70000013 SALONI TANEJA ATAM PARKASH SANTOSH RANI 4 MILE STONE BAJEKAN MORE BAJEKAN HISAR ROAD SIRSASIRSASirsa PGT Computer Science 70000014 MONIKA NATH SOM NATH AVINASH HOUSE NO-1387 SECTOR-26PANCHKULAPanchkula PGT Computer Science 70000015 ANUPRIYA SURESH KUMAR SHAKUNTLA H.no 50-A/29, Chankya PuriROHTAKRohtak PGT Computer Science 70000016 SANDEEP KUMAR RAJINDER SINGH NIRMLA DEVI HOUSE NO. 38,SARSWATI VIHAR VPO SINGAWALA AMBALA CITYAMBALA CITYAmbala PGT Computer Science 70000017 RICHA KUKREJA RAMESH KUMAR KUKREJA PREM KUKREJA H.NO. 113 SECTOR 20 HUDA KAITHALKAITHALKaithal PGT Computer Science 70000018 Sneha Bahl Rajinder Singh Bahl Rama Bahl House No. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The Social Structure and Organization of A Pakhto Speaking Community in Afghanistan. Evans-Von Krbek, Jerey Hewitt Pollitt How to cite: Evans-Von Krbek, Jerey Hewitt Pollitt (1977) The Social Structure and Organization of A Pakhto Speaking Community in Afghanistan., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1866/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE SOCIAL STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION OF A PAKHTO SPEAKING COMMUNITY IN AFGHANISTAN Ph. D. Thesis, 1977 Jeffrey H. P. Evans-von Krbek Department of Anthropology University of Durham The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. ABSTRACT The Safi of Afghaniya, one of the tribal sections of the Safi Pakhtuns (Pathans) of Afghanistan, constitute the subject of study in the thesis.