Dreadlocks Editor: Mohit Prasad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Exploratory Study on Origin of AI: Journey Through the Ancient Indian Texts & Other Technological Descriptions, Its Past, Present & Future

An Exploratory Study On Origin Of AI: Journey Through The Ancient Indian Texts & Other Technological Descriptions, Its Past, Present & Future Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry (TOJQI) Volume 12, Issue 7, July 2021: 6527- 6555 Research Article An Exploratory Study On Origin Of AI: Journey Through The Ancient Indian Texts & Other Technological Descriptions, Its Past, Present & Future Mrinmoy Roy PhD Scholar Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, Punjab Abstract For the modern world and our present civilization the invention of the first programmable digital computer taken place in the 1940s, a machine based on mathematical reasoning, this knowledge & ideas inspired few scientists to seriously think of building Artificial Intelligence. The modern world also knows that a British Polymath, Alan Turing in the year 1950, suggested the concept of decision science, artificial intelligence and machines solving the real world problems. The first commercial, digital & programmable robot was made by Geroge Devol in 1954, the field of AI research was founded at a workshop held on the campus of Dartmouth College during the summer of 1956. But modern world is not aware of the origin of Artificial Intelligence (AI) began back in 8000 to 11000 years, with myths, stories and rumors of artificial beings endowed with intelligence or consciousness by ancient Rishis of India. The seeds of modern AI were planted by classical philosophers who attempted to describe the process of human thinking as the mechanical manipulation of symbols. This work culminated through Knowledge and ideas on many of the technological advancement that we are witnessing today had already been articulated in holy books of Hinduism like The Ramayana, The Mahabharata, The Bhagawatgeeta, The Vedas & Upanishads which were believed to be written 5000 to 8000 years ago (3000 BC – 6000 BC). -

Ethnography of Ontong Java and Tasman Islands with Remarks Re: the Marqueen and Abgarris Islands

PACIFIC STUDIES Vol. 9, No. 3 July 1986 ETHNOGRAPHY OF ONTONG JAVA AND TASMAN ISLANDS WITH REMARKS RE: THE MARQUEEN AND ABGARRIS ISLANDS by R. Parkinson Translated by Rose S. Hartmann, M.D. Introduced and Annotated by Richard Feinberg Kent State University INTRODUCTION The Polynesian outliers for years have held a special place in Oceanic studies. They have figured prominently in discussions of Polynesian set- tlement from Thilenius (1902), Churchill (1911), and Rivers (1914) to Bayard (1976) and Kirch and Yen (1982). Scattered strategically through territory generally regarded as either Melanesian or Microne- sian, they illustrate to varying degrees a merging of elements from the three great Oceanic culture areas—thus potentially illuminating pro- cesses of cultural diffusion. And as small bits of land, remote from urban and administrative centers, they have only relatively recently experienced the sustained European contact that many decades earlier wreaked havoc with most islands of the “Polynesian Triangle.” The last of these characteristics has made the outliers particularly attractive to scholars interested in glimpsing Polynesian cultures and societies that have been but minimally influenced by Western ideas and Pacific Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3—July 1986 1 2 Pacific Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3—July 1986 accoutrements. For example, Tikopia and Anuta in the eastern Solo- mons are exceptional in having maintained their traditional social structures, including their hereditary chieftainships, almost entirely intact. And Papua New Guinea’s three Polynesian outliers—Nukuria, Nukumanu, and Takuu—may be the only Polynesian islands that still systematically prohibit Christian missionary activities while proudly maintaining important elements of their old religions. -

Kumari Kandam – Mother Land Volume :1 Issue: 1

KUMARI KANDAM – MOTHER LAND VOLUME :1 ISSUE: 1 KUMARI KANDAM Mother Land September 2018 Contents 1. Message from Shri Rejith Kumar – Mayura Simhasanam 2. Lion Mayura Royal Kingdom 3. Shri Rejith Kumar – A Divine Instrument of Muruga Peruman 4. Significance of Kumari Kandam in the New Muruga Yugam 5. Murugan Adiargal – Kachiappa Sivachariar 6. LMRK News – August 2018 7. Devotee Experiences 8. Upcoming Events 9. From Editor’s Desk © Lion Mayura Royal Kingdom - 1 - September 2018 KUMARI KANDAM – MOTHER LAND VOLUME :1 ISSUE: 1 MESSAGE FROM SHRI REJITH KUMAR- MAYURA SIMHASANAM Namaste to all! Lion Mayura Royal Kingdom (LMRK) is the name of our organisation. The specialty of this organization is that it has been created and is run by Muruga Peruman Himself. The Muruga Yugam has begun. A very important step has been taken. Muruga Peruman has started this organisation to last for many thousands of years. The significance of the Muruga Yugam is as follows: SHRI REJITH KUMAR • Muruga worship will increase all over the world. • It is the age of the Siddhars. The power of Siddhar science will be known and many people will come forward to research this. • World will come to know about the advance knowledge and the greatness of the Tamil civilization. The fame of Tamil civilization will rise again. And it is for this very purpose, this organisation LMRK has been started. The first and most important task, through the grace of Muruga Peruman is the pradishta of the Mayura Simhasanam at Wales. The pradishta is to happen on the 14th of November 2018 at ‘Thanthondri Anjaneyar Temple’ at Wales (Zero time zone). -

Solar Moon of Intention • Noos-Letter of the Foundation for the Law of Time

Solar Moon of Intention • Noos-letter of the Foundation for the Law of Time • Issue #34 Sign up! • Unsubscribe • Change your address Trouble viewing? Click here to view online • Share! Welcome to the Solar Jaguar Moon Edition of the Noos-letter Welcome to the Solar Jaguar Moon of Intention, the ninth moon of the Planetary Service Wavespell. "Do not underestimate the power of your own clear mind thought and actions. Through the synchronic codes of the Law of Time, we are all activating the noosphere, an invisible action to pay off in the manifestation of the Rainbow Bridge." –Valum Votan We have now entered the third of seven Mystic Moons – the Moon of the Yellow Solar Seed. Yellow Solar Seed, Kin 204, is the galactic signature of the great Russian diplomat, scientist, visionary artist and peace worker, Nicholas Roerich, who shares his solar birthday (Gregorian October 9) with John Lennon. Roerich and his wife, Helena, went to Central Asia in the 1920s in search for Shambhala, the enlightened society. The Roerich's returned from their journey with the Banner of Peace, which has since been adopted by the World Thirteen Moon Calendar Change Peace Movement as one of its official standards. Song of Shambhala - by Nicholas Roerich Shambhala is the fulfillment of the prophecies of Kalachakra, the wheel of time. The Kalachakra ends in the Kali yuga, the dark age of ignorance and destruction of the Earth because humans are living in artificial time. 1987 fulfilled the cycle of prophecies of Kalachakra and Quetzalcoatl (Harmonic Convergence). 2012 signaled the closing of the cycle and the phasing out of a particular galactic beam, 5,125 years in diameter. -

Governance and Leadership

Dr. Vaishnavanghri Sevaka Das, Ph.D. Director, Bhaktivedanta College of Vedic Education Affiliated to ISKCON, Navi Mumbai 1 Governance and Leadership Governance “the action or manner of governing a state, organization, etc. for enhancing prosperity and sustenance” Leadership “the state or position of being a leader for ensuring the good Governance” 2 Four Yugas and Yuga Chakra Our Position (Fixed) Kali Yuga Dwapara Yuga 4,32,000 Years 8,64,000 Years 10% 20% 1 Yuga Chakra 43,20,000 Years 40% 30% Satya Yuga Treta Yuga 17,28,000 Years 12,96,000 Years 1000 Rotations of the Yuga Chakra = 1 Day of Brahma Ji 1000 Rotations of the Yuga Chakra = 1 Night of Brahma Ji 3 Concept of Four Quotients Spiritually Intellectually Strong Sharp Physically Mentally Fit Balanced 4 Test Your Understanding of the Four Quotients • Rakesh is getting ready for his final semester exam. Because of his night out he is weak and tensed. • Rakesh’s father Rajaram came from morning jogging with heavy sweating and comforted his son with inspirational words. • Rakesh’s mother Shanti did special prayers to Lord Ganesha for all success to her son but she is also very tensed. • Rakesh’s sister Rakhi gave best wishes to him and put a tilak. She reminded him of his strengths and also warned him of weakness of getting nervous. • Rakesh got onto his bike and started speeding towards his college. He is tensed as his thoughts were also speeding on top gear. • Rakesh stopped on the road when he saw his classmate Abhay with whom he never spoke. -

When Did Kali Yuga Start, How Long Is/Was It, and When Will It (Or Did It) End?

When did Kali Yuga start, how long is/was it, and when will it (or did it) end? In the book The Holy Science (1894) Sri Yukteswar clarified that a complete Yuga Cycle takes 24,000 years, and is comprised of an ascending cycle of 12,000 years when virtue gradually increases and a descending cycle of another 12,000 years, in which virtue gradually decreases (See the above figure). Hence, after we complete a 12,000-year descending cycle from Satya Yuga -> Kali Yuga, the sequence reverses itself, and an ascending cycle of 12,000 years begins which goes from Kali Yuga -> Satya Yuga. Yukteswar states that, “Each of these periods of 12,000 years brings a complete change, both externally in the material world, and internally in the intellectual or electric world, and is called one of the Daiva Yugas or Electric Couple.” Unfortunately, the start and end dates as well as the duration of the ages are not agreed upon, and Sri Yukteswar (who I have deep faith in) is one of many individuals that have laid out differing dates, times, and structures. “In spite of the elaborate theological framework of the Yuga Cycle, the start and end dates of the Kali Yuga remain shrouded in mystery. The popularly accepted date for the beginning of the Kali Yuga is 3102 BCE, thirty-five years after the conclusion of the battle of the Mahabharata.” This quote is taken from a well-researched article, “The End of the Kali Yuga in 2025: Unravelling the Mysteries of the Yuga Cycle in the New Dawn online magazine which can be found HERE. -

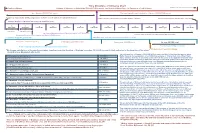

Time Structure of Universe Chart

Time Structure of Universe Chart Creation of Universe Lifespan of Universe - 1 Maha Kalpa (311.040 Trillion years, One Breath of Maha-Visnu - An Expansion of Lord Krishna) Complete destruction of Universe Age of Universe: 155.52197 Trillion years Time remaining until complete destruction of Universe: 155.51803 Trillion years At beginning of Brahma's day, all living beings become manifest from the unmanifest state (Bhagavad-Gita 8.18) 1st day of Brahma in his 51st year (current time position of Brahma) When night falls, all living beings become unmanifest 1 Kalpa (Daytime of Brahma, 12 hours)=4.32 Billion years 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas 1 Manvantara 306.72 Million years Age of current Manvantara and current Manu (Vaivasvata): 120.533 Million years Time remaining for current day of Brahma: 2.347051 Billion years Between each Manvantara there is a juncture (sandhya) of 1.728 Million years 1 Chaturyuga (4 yugas)=4.32 Million years 28th Chaturyuga of the 7th manvantara (current time position) Satya-yuga (1.728 million years) Treta-yuga (1.296 million years) Dvapara-yuga (864,000 years) Kali-yuga (432,000 years) Time remaining for Kali-yuga: 427,000 years At end of each yuga and at the start of a new yuga, there is a juncture period 5000 years (current time position in Kali-yuga) "By human calculation, a thousand ages taken together form the duration of Brahma's one day [4.32 billion years]. -

The Calendars of India

The Calendars of India By Vinod K. Mishra, Ph.D. 1 Preface. 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Basic Astronomy behind the Calendars 8 2.1 Different Kinds of Days 8 2.2 Different Kinds of Months 9 2.2.1 Synodic Month 9 2.2.2 Sidereal Month 11 2.2.3 Anomalistic Month 12 2.2.4 Draconic Month 13 2.2.5 Tropical Month 15 2.2.6 Other Lunar Periodicities 15 2.3 Different Kinds of Years 16 2.3.1 Lunar Year 17 2.3.2 Tropical Year 18 2.3.3 Siderial Year 19 2.3.4 Anomalistic Year 19 2.4 Precession of Equinoxes 19 2.5 Nutation 21 2.6 Planetary Motions 22 3. Types of Calendars 22 3.1 Lunar Calendar: Structure 23 3.2 Lunar Calendar: Example 24 3.3 Solar Calendar: Structure 26 3.4 Solar Calendar: Examples 27 3.4.1 Julian Calendar 27 3.4.2 Gregorian Calendar 28 3.4.3 Pre-Islamic Egyptian Calendar 30 3.4.4 Iranian Calendar 31 3.5 Lunisolar calendars: Structure 32 3.5.1 Method of Cycles 32 3.5.2 Improvements over Metonic Cycle 34 3.5.3 A Mathematical Model for Intercalation 34 3.5.3 Intercalation in India 35 3.6 Lunisolar Calendars: Examples 36 3.6.1 Chinese Lunisolar Year 36 3.6.2 Pre-Christian Greek Lunisolar Year 37 3.6.3 Jewish Lunisolar Year 38 3.7 Non-Astronomical Calendars 38 4. Indian Calendars 42 4.1 Traditional (Siderial Solar) 42 4.2 National Reformed (Tropical Solar) 49 4.3 The Nānakshāhī Calendar (Tropical Solar) 51 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year 52 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year (vaisnava) 58 5. -

Notornis June 04.Indd

Notornis, 2004, Vol. 51: 91-102 91 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. 2003 Birds of the northern atolls of the North Solomons Province of Papua New Guinea DON W. HADDEN P.O. Box 6054, Christchurch 8030, New Zealand [email protected] Abstract The North Solomons Province of Papua New Guinea consists of two main islands, Bougainville and Buka as well as several atolls to the north and east. The avifauna on five atolls, Nissan, Nuguria, Tulun, Takuu and Nukumanu, was recorded during visits in 2001. A bird list for each atoll group was compiled, incorporating previously published observations, and the local language names of birds recorded. Hadden, D.W. 2004. Birds of the northern atolls of the North Solomons Province of Papua New Guinea. Notornis 51(2): 91-102 Keywords bird-lists; Nissan; Nuguria; Tulun; Takuu; Nukumanu; Papua New Guinea; avifauna INTRODUCTION Grade 6 students had to be taken by Nukumanu North of Buka Island, in the North Solomons students. Over two days an examiner supervised Province of Papua New Guinea lie several small the exams and then the ship was able to return. atolls including Nissan (4º30’S 154º12’E), Nuguria, A third purpose of the voyage was to provide food also known as Fead (3º20’S 154º40’E), Tulun, also aid for the Tulun people. Possibly because of rising known as Carterets or Kilinailau (4º46’S 155º02’E), sea levels, the gardens of the Tulun atolls are now Takuu, also known as Tauu or Mortlocks (4º45’S too saline to grow vegetables. The atolls’ District 157ºE), and Nukumanu, also known as Tasmans Manager based in Buka is actively searching for (4º34’S 159º24’E). -

VII the Eastern Islands (Nuguria, Tauu and Nukumanu)

THE EASTERN ISLANDS (NUGURIA, TAUU AND NUKUMANU) VII The Eastern Islands (Nuguria, Tauu and Nukumanu) ast of the large Melanesian islands extends a For years the population has been in the process Elong chain of small islands, mostly raised of dying out. The current number is about fifteen. coral reefs or atolls, belonging geographically to In 1902 alone, sixteen died, particularly as a result Melanesia, but occupying a quite special position of influenza. The natives’ physical resistance seems ethnographically. to be very low, and it will not be many more years Three of these small atolls, Nuguria, Tauu and before none of the present population exists. In Nukumanu, have been annexed by the German 1885 when I first visited this small group I esti- protectorate. A fourth group, Liueniua or Ong mated the population to be at least 160 people. tong Java, by far the most significant, was Ger - Tauu, pronounced Tau’u’u (Mortlock or Mar- man for a time but then by treaty passed into queen Islands; Dr Thilenius names it incorrectly as English hands. Taguu), is likewise an atoll structure. It lies at ap- Although the three German groups are of no proximately 157ºE longitude and 4º50’S latitude, great interest commercially and probably never and the total land area of the islands is no greater will be, ethnographically they are of no small im- than 200 hectares. The distance from Nuguria is portance because in spite of being in a Melanesian about 150 nautical miles. The nearest point in the neighbourhood, they are inhabited by Polynesians. -

Promoting Human Security and Minimizing Conflict Associated with Forced Migration in the Pacific Region

PACIFIC RESEARCH PROJect PROMOTING HUMAN SECURITY AND MINIMIZING CONFLICT ASSOCIATED WITH FORCED MIGRATION IN THE PACIFIC REGION Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat United Nations University Institute on Globalization, Culture and Mobility United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security CORENDEA, Cosmin · BELLO, Valeria · and BRYAR, Timothy POLICY BRIEF SEPTEMBER 2015 PROMOTING HUMAN SECURITY AND MINIMIZING CONFLICT ASSOCIATED WITH FORCED MIGRATION IN THE PACIFIC REGION THE PACIFIC IN WITH FORCED MIGRATION ASSOCIATED AND MINIMIZING CONFLICT HUMAN SECURITY PROMOTING 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research team would like to express their thanks to Ms. Andie Fong-Toy -Acting Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat- and to Prof. Parvati Nair -Director of UNU-GCM- for supporting the research activities of Table of contents the Pacific research project. The research team is also extremely thankful to Prof. Jacob Rhyner –Vice Rector of the United Nations University in Europe PURPOSE OF THIS DOCUMENT ......................................................................................... 05 and Director of UNU-EHS- for his crucial collaboration and to all the persons SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................07 from the United Nations University and the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, along with all the Peoples and Institutions and Organizations in the Pacific, ABBREVIATIONS AND AcRONYMS .................................................................................. -

Genealogy and the Vedic Timescale Sai Venkatesh

Genealogy and the Vedic Timescale Sai Venkatesh The Renowned Astronomer and Cosmologist Carl Sagan once said “The Hindu religion is the only one of the world’s great faiths dedicated to the idea that the Cosmos itself undergoes an immense, indeed an infinite, number of deaths and rebirths. It is the only religion in which the time scales correspond to those of modern scientific cosmology. Its cycles run from our ordinary day and night to a day and night of Brahma, 8.64 billion years long. Longer than the age of the Earth or the Sun and about half the time since the Big Bang”. True enough, Vedic Wisdom beautifully encompasses all facets of nature uncovered only recently by modern science - quantum mechanics, chaos theory, particle physics, big bang, cosmology, dark matter and dark energy, genetic code and an ultimate theory of everything emergent from mathematical symmetry and perfection bridging algebra and geometry through the largest possible Exceptionally Simple Lie Group Structure, the E8. The previous articles have dealt with explaining these aspects of the universe all the way from before the Big Bang until present day life on earth. The corresponding perspectives in Vedic wisdom have also been outlined, in most cases where these universal concepts are alluded to deities such as Adityas, Vasus, Rudras, Ashvinis and so on. (viXra:1808.0371, viXra:1808.0528, viXra:1809.0099) Building on this, the focus of the present article is the Vedic Timescale, and how they map to current understanding of science. In decreasing order of duration one may consider the Vedic Timescales as Mahapralaya, Pralaya, Kalpas, Manvantaras and finally Yugas.