The Reptile and Amphibian Fauna Found at Quail Ridge Reserve Is a Relatively

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evidence of Lingual-Luring by an Aquatic Snake

Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 34 No. 1 pp 67-74, 2000 Copyright 2000 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Evidence of Lingual-luring by an Aquatic Snake HARTWELL H. WELSH, JR. AND AMY J. LIND Pacific Southwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 1700 Bayview Dr., Arcata, California 95521, USA. E-mail: hwelsh/[email protected] ABSTRACT.-We describe and quantify the components of an unusual snake behavior used to attract fish prey: lingual-luring. Our earlier research on the foraging behavior of the Pacific Coast aquatic garter snake (Thamnophis atratus) indicated that adults are active foragers, feeding primarily on aquatic Pacific giant salamanders (Dicamptodon tenebrosus) in streambed substrates. Juvenile snakes, however, use primarily ambush tactics to capture larval anurans and juvenile salmonids along stream margins, behaviors that include the lingual-luring described here. We found that lingual-luring differed from typical chemosensory tongue-flicking by the position of the snake, contact of the tongue with the water surface, and the length of time the tongue was extended. Luring snakes are in ambush position and extend and hold their tongues out rigid, with the tongue-tips quivering on the water surface, apparently mimicking insects in order to draw young fish within striking range. This behavior is a novel adaptation of the tongue-vomeronasal system by a visually-oriented predator. The luring of prey by snakes has been asso- luring function (Mushinsky, 1987; Ford and ciated primarily with the use of the tail, a be- Burghardt, 1993). However, Lillywhite and Hen- havior termed caudal luring (e.g., Neill, 1960; derson (1993) noted the occurrence of a pro- Greene and Campbell, 1972; Heatwole and Dav- longed extension of the tongue observed in vine ison, 1976; Jackson and Martin, 1980; Schuett et snakes (e.g., Kennedy, 1965; Henderson and al., 1984; Chizar et al., 1990). -

The Plant Press the ARIZONA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY

The Plant Press THE ARIZONA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY Volume 36, Number 1 Summer 2013 In this Issue: Plants of the Madrean Archipelago 1-4 Floras in the Madrean Archipelago Conference 5-8 Abstracts of Botanical Papers Presented in the Madrean Archipelago Conference Southwest Coralbean (Erythrina flabelliformis). Plus 11-19 Conservation Priority Floras in the Madrean Archipelago Setting for Arizona G1 Conference and G2 Plant Species: A Regional Assessment by Thomas R. Van Devender1. Photos courtesy the author. & Our Regular Features Today the term ‘bioblitz’ is popular, meaning an intensive effort in a short period to document the diversity of animals and plants in an area. The first bioblitz in the southwestern 2 President’s Note United States was the 1848-1855 survey of the new boundary between the United States and Mexico after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848 ended the Mexican-American War. 8 Who’s Who at AZNPS The border between El Paso, Texas and the Colorado River in Arizona was surveyed in 1855- 9 & 17 Book Reviews 1856, following the Gadsden Purchase in 1853. Besides surveying and marking the border with monuments, these were expeditions that made extensive animal and plant collections, 10 Spotlight on a Native often by U.S. Army physicians. Botanists John M. Bigelow (Charphochaete bigelovii), Charles Plant C. Parry (Agave parryi), Arthur C. V. Schott (Stephanomeria schotti), Edmund K. Smith (Rhamnus smithii), George Thurber (Stenocereus thurberi), and Charles Wright (Cheilanthes wrightii) made the first systematic plant collection in the Arizona-Sonora borderlands. ©2013 Arizona Native Plant In 1892-94, Edgar A. Mearns collected 30,000 animal and plant specimens on the second Society. -

Reptile and Amphibian List RUSS 2009 UPDATE

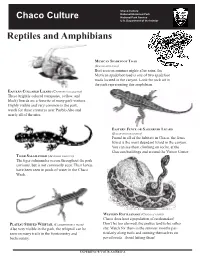

National CHistoricalhaco Culture Park National ParkNational Service Historical Park Chaco Culture U.S. DepartmentNational of Park the Interior Service U.S. Department of the Interior Reptiles and Amphibians MEXICAN SPADEFOOT TOAD (SPEA MULTIPLICATA) Best seen on summer nights after rains, the Mexican spadefoot toad is one of two spadefoot toads located in the canyon. Look for rock art in the park representing this amphibian. EASTERN COLLARED LIZARD (CROTAPHYTUS COLLARIS) These brightly colored (turquoise, yellow, and black) lizards are a favorite of many park visitors. Highly visible and very common in the park, watch for these creatures near Pueblo Alto and nearly all of the sites. EASTERN FENCE OR SAGEBRUSH LIZARD (SCELOPORUS GRACIOSUS) Found in all of the habitats in Chaco, the fence lizard is the most abundant lizard in the canyon. You can see them climbing on rocks, at the Chacoan buildings and around the Visitor Center. TIGER SALAMANDER (ABYSTOMA TIGRINUM) The tiger salamander occurs throughout the park environs, but is not commonly seen. Their larvae have been seen in pools of water in the Chaco Wash. WESTERN RATTLESNAKE (CROTALUS VIRIDIS) Chaco does host a population of rattlesnakes! PLATEAU STRIPED WHIPTAIL (CNEMIDOPHORUS VALOR) Don’t be too alarmed, the snakes tend to be rather Also very visible in the park, the whiptail can be shy. Watch for them in the summer months par- seen on many trails in the frontcountry and ticularly along trails and sunning themselves on backcountry. paved roads. Avoid hitting them! EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA Amphibian and Reptile List Chaco Culture National Historical Park is home to a wide variety of amphibians and reptiles. -

Multi-National Conservation of Alligator Lizards

MULTI-NATIONAL CONSERVATION OF ALLIGATOR LIZARDS: APPLIED SOCIOECOLOGICAL LESSONS FROM A FLAGSHIP GROUP by ADAM G. CLAUSE (Under the Direction of John Maerz) ABSTRACT The Anthropocene is defined by unprecedented human influence on the biosphere. Integrative conservation recognizes this inextricable coupling of human and natural systems, and mobilizes multiple epistemologies to seek equitable, enduring solutions to complex socioecological issues. Although a central motivation of global conservation practice is to protect at-risk species, such organisms may be the subject of competing social perspectives that can impede robust interventions. Furthermore, imperiled species are often chronically understudied, which prevents the immediate application of data-driven quantitative modeling approaches in conservation decision making. Instead, real-world management goals are regularly prioritized on the basis of expert opinion. Here, I explore how an organismal natural history perspective, when grounded in a critique of established human judgements, can help resolve socioecological conflicts and contextualize perceived threats related to threatened species conservation and policy development. To achieve this, I leverage a multi-national system anchored by a diverse, enigmatic, and often endangered New World clade: alligator lizards. Using a threat analysis and status assessment, I show that one recent petition to list a California alligator lizard, Elgaria panamintina, under the US Endangered Species Act often contradicts the best available science. -

3.4 Biological Resources for the Purpose of This EIR, Biological Resources Comprise Vegetation, Wildlife, Natural Communities, and Wetlands and Other Waters

Impact Analysis Alameda County Community Development Agency Biological Resources 3.4 Biological Resources For the purpose of this EIR, biological resources comprise vegetation, wildlife, natural communities, and wetlands and other waters. Potential biological resource impacts associated with the program and the two individual projects are analyzed. Potential impacts are described quantitatively and qualitatively in Section 3.4.2, Environmental Impacts. This section also identifies specific and detailed measures to avoid, minimize, or compensate for potentially significant impacts on biological resources, where necessary. 3.4.1 Existing Conditions Regulatory Setting Federal Endangered Species Act Pursuant to the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), USFWS and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) have authority over projects that may result in take of a species listed as threatened or endangered under the act. Take is defined under the ESA, in part, as killing, harming, or harassing. Under federal regulations, take is further defined to include habitat modification or degradation that results, or is reasonably expected to result, in death or injury to wildlife by significantly impairing essential behavioral patterns, including breeding, feeding, or sheltering. If a likelihood exists that a project would result in take of a federally listed species, either an incidental take permit, under Section 10(a) of the ESA, or a federal interagency consultation, under Section 7 of the ESA, is required. Several federally listed species—vernal pool fairy shrimp (Branchinecta lynchi), longhorn fairy shrimp (Branchinecta longiantenna), vernal pool tadpole shrimp (Lepidurus packardi), California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense), California red‐legged frog (Rana draytonii), Alameda whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus), and San Joaquin kit fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica)—have the potential to be affected by activities associated with the Golden Hills and Patterson Pass projects as well as subsequent repowering projects. -

EUROPEAN WALL LIZARDS (Podarcis Muralis)

INVASIVE SPECIES ALERT! EUROPEAN WALL LIZARDS (Podarcis muralis) NATIVE RANGE European Wall Lizards are native to southern Belgium and Germany, south to northern Spain, and east to Turkey. The European Wall Lizards in B.C. are thought to be native to Italy. DESCRIPTION European Wall Lizards... Have a long, slender, flattened body Photo: Gavin Hanke Can grow to be 63 mm in length (snout to base of tail) Can have a tail 1.5 times the length of body Have small, bead-like scales on back and sides PRIMARY IMPACT: Have 6 rows of large rectangular scales on belly region Have long fingers and toes European Wall Do not have skin folds on back and sides of body Lizards may impact Are variable in colour, ranging from brown to grey to green May have black-blue spots on the flank (especially males) native species Adults usually have prominent flecks of green on the back, intensely through competition coloured over the shoulders and predation. WHY SHOULD WE CARE? European Wall Lizards... Can gather in large densities, which can potentially impact native DID YOU KNOW? species and ecosystems that are not adapted to their presence If a European Wall Lizard is Could compete for food and shelter with B.C.’s native Northern captured, it will drop its tail to Alligator Lizard (Elgaria coerulea) or endangered Sharp-Tailed Snake (Contia tenuis) escape. The tail keeps wiggling for a few minutes in order to LOOKALIKES distract the predator, giving European Wall Lizards can be confused with native Northern Alligator Lizards the lizard a chance to escape. -

Bio 308-Course Guide

COURSE GUIDE BIO 308 BIOGEOGRAPHY Course Team Dr. Kelechi L. Njoku (Course Developer/Writer) Professor A. Adebanjo (Programme Leader)- NOUN Abiodun E. Adams (Course Coordinator)-NOUN NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island Lagos Abuja Office No. 5 Dar es Salaam Street Off Aminu Kano Crescent Wuse II, Abuja e-mail: [email protected] URL: www.nou.edu.ng Published by National Open University of Nigeria Printed 2013 ISBN: 978-058-434-X All Rights Reserved Printed by: ii BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ……………………………………......................... iv What you will Learn from this Course …………………............ iv Course Aims ……………………………………………............ iv Course Objectives …………………………………………....... iv Working through this Course …………………………….......... v Course Materials ………………………………………….......... v Study Units ………………………………………………......... v Textbooks and References ………………………………........... vi Assessment ……………………………………………….......... vi End of Course Examination and Grading..................................... vi Course Marking Scheme................................................................ vii Presentation Schedule.................................................................... vii Tutor-Marked Assignment ……………………………….......... vii Tutors and Tutorials....................................................................... viii iii BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE INTRODUCTION BIO 308: Biogeography is a one-semester, 2 credit- hour course in Biology. It is a 300 level, second semester undergraduate course offered to students admitted in the School of Science and Technology, School of Education who are offering Biology or related programmes. The course guide tells you briefly what the course is all about, what course materials you will be using and how you can work your way through these materials. It gives you some guidance on your Tutor- Marked Assignments. There are Self-Assessment Exercises within the body of a unit and/or at the end of each unit. -

Fish and Wildlife

Appendix B Upper Middle Mainstem Columbia River Subbasin Fish and Wildlife Table 2 Wildlife species occurrence by focal habitat type in the UMM Subbasin, WA. -

Northern Alligator Lizard Elgaria Coerulea (Weigmann,1828) Natural History Summary by Kate Durost

NORTHERN ALLIGATOR LIZARD ELGARIA COERULEA (WEIGMANN,1828) NATURAL HISTORY SUMMARY BY KATE DUROST Classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Reptilia Order: Squamata Family: Anguidae Genus: Elgaria Species: E. coerulea Description The Northern Alligator Lizard (Elgaria coerulea) ranges in color from gray, olive, and rust, to greenish or bluish dorsally with heavy blotching or barring in a dusky color. Its eyes are completely dark or dark around the pupils. There are dark stripes between the scale rows on the belly, though they can sometimes be absent. Dorsal scales are usually in 16 rows. Four subspecies have been described: E. c. coerulea, E. c. shastensis, E. c. principis, and E. c. palmeri, with E. c. principis, or the Northwestern Alligator Lizard being the one most likely to be found in Washington. The Northwestern Alligator Lizard tends to be small – less than 4 in long, with a broad dorsal stripe of tan, olive, golden brown, or gray and contrasting dusky sides. The dorsal scales are weakly keeled in 14 rows with the temporal scales also being weakly keeled (Stebbins 2003). Distribution The Northern Alligator Lizard is found along the western coast of North America. Elgaria coeruela principis has the largest range of any of the subspecies, ranging from southern Oregon to British Columbia, Canada while the others are concentrated in California (CaliforniaHerps 2017). Elgaria coerulea’s range map is available at Hammerson 2007. Diet The Northern Alligator Lizard primarily eats a variety of small invertebrates like ticks, spiders, centipedes, slugs, millipedes, snails, and worms as well as any of their larvae. It will also eat small lizards and small mammals and occasionally feed on bird eggs and young birds (CaliforniaHerps, 2017; Stebbins 2003). -

Taricha Rivularis) in California Presents Conservation Challenges Author(S): Sean B

Discovery of a New, Disjunct Population of a Narrowly Distributed Salamander (Taricha rivularis) in California Presents Conservation Challenges Author(s): Sean B. Reilly, Daniel M. Portik, Michelle S. Koo, and David B. Wake Source: Journal of Herpetology, 48(3):371-379. 2014. Published By: The Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1670/13-066 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1670/13-066 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 48, No. 3, 371–379, 2014 Copyright 2014 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Discovery of a New, Disjunct Population of a Narrowly Distributed Salamander (Taricha rivularis) in California Presents Conservation Challenges 1 SEAN B. REILLY, DANIEL M. PORTIK,MICHELLE S. KOO, AND DAVID B. WAKE Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, 3101 Valley Life Sciences Building, Berkeley, California 94720 USA ABSTRACT. -

Expanded Description of a Chinese Endemic Snake Opisthotropis Cheni (Serpentes: Colubridae: Natricinae)

Asian Herpetological Research 2010, 1(1): 57-60 DOI: 10.3724/SP.J.1245.2010.00057 Expanded Description of a Chinese Endemic Snake Opisthotropis cheni (Serpentes: Colubridae: Natricinae) LI Cao1, LIU Qin1 and GUO Peng 1, 2* 1 Department of Life Sciences and Food Engineering, Yibin University, Yibin 644000, Sichuan, China 2 Chendgu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan, China Abstract Based on seven newly-collected specimens, we provide an expanded description for the rare Chinese snake Opisthotropis cheni. The new specimens are consistent with the type series in scale counts and body dimensions. How- ever, two individuals lack yellow cross-bands that are apparent in the type specimens. A key to the ten Chinese species of Opisthotropis is provided. Keywords snake, Opisthotropis cheni, morphology, China 1. Introduction 070140, 071041, 071046-071050) (Table 1), collected from the Nanling National Nature Reserve in Ruyuan The genus Opisthotropis Gǘnther (1872) is comprised of County, Guangdong Province, China (Figure 1), were 17 currently recognized species, and is widely distributed morphologically examined in this work. The specimens in eastern, southern, and southeastern Asia (Uetz, 2010). were preserved in 8% formalin for initial fixation, and Members of this genus are all small aquatic snakes, later transferred to 75% ethanol. All specimens were de- mainly inhabiting rapidly flowing streams or small rivers. posited at Yibin University (YBU), Sichuan Province, Ten species of Opisthotropis occur in China (Zhao, China. 2006). Snout-vent length (SVL) and tail length (TL) were Zhao (1999) described Opisthotropis cheni based on measured using a meter ruler to the nearest millimeter, four specimens collected from Mt. -

USGS DDS-43, Status of Terrestrial Vertebrates

DAVID M. GRABER National Biological Service Sequoia and Kings Canyon Field Station Three Rivers, California 25 Status of Terrestrial Vertebrates ABSTRACT The terrestrial vertebrate wildlife of the Sierra Nevada is represented INTRODUCTION by about 401 regularly occurring species, including three local extir- There are approximately 401 species of terrestrial vertebrates pations in the 20th century. The mountain range includes about two- that use the Sierra Nevada now or in recent times according thirds of the bird and mammal species and about half the reptiles to the California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System and amphibians in the State of California. This is principally because (CWHR) (California Department of Fish and Game 1994) (ap- of its great extent, and because its foothill woodlands and chaparral, pendix 25.1). Of these, thirteen are essentially restricted to mid-elevation forests, and alpine vegetation reflect, in structure and the Sierra in California (one of these is an alien; i.e. not native function if not species, habitats found elsewhere in the State. About to the Sierra Nevada); 278 (eight aliens) include the Sierra in 17% of the Sierran vertebrate species are considered at risk by state their principal range; and another 110 (six aliens) use the Si- or federal agencies; this figure is only slightly more than half the spe- erra as a minor portion of their range. Included in the 401 are cies at risk for the state as a whole. This relative security is a function 232 species of birds; 112 species of mammals; thirty-two spe- of the smaller proportion of Sierran habitats that have been exten- cies of reptiles; and twenty-five species of amphibians (ap- sively modified.