Urban Alternatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fællesrådenes Adresser

Fællesrådenes adresser Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail Kirkebakken 23 Beder-Malling-Ajstrup Fællesråd Jørgen Friis Bak [email protected] 8330 Beder Langelinie 69 Borum-Lyngby Fællesråd Peter Poulsen Borum 8471 Sabro [email protected] Holger Lyngklip Hoffmannsvej 1 Brabrand-Årslev Fællesråd [email protected] Strøm 8220 Brabrand Møllevangs Allé 167A Christiansbjerg Fællesråd Mette K. Hagensen [email protected] 8200 Aarhus N Jeppe Spure Hans Broges Gade 5, 2. Frederiksbjerg og Langenæs Fællesråd [email protected] Nielsen 8000 Aarhus C Hastruptoften 17 Fællesrådet Hjortshøj Landsbyforum Bjarne S. Bendtsen [email protected] 8530 Hjortshøj Poul Møller Blegdammen 7, st. Fællesrådet for Mølleparken-Vesterbro [email protected] Andersen 8000 Aarhus C [email protected] Fællesrådet for Møllevangen-Fuglebakken- Svenning B. Stendalsvej 13, 1.th. Frydenlund-Charlottenhøj Madsen 8210 Aarhus V Fællesrådet for Aarhus Ø og de bynære Jan Schrøder Helga Pedersens Gade 17, [email protected] havnearealer Christiansen 7. 2, 8000 Aarhus C Gudrunsvej 76, 7. th. Gellerup Fællesråd Helle Hansen [email protected] 8220 Brabrand Jakob Gade Øster Kringelvej 30 B Gl. Egå Fællesråd [email protected] Thomadsen 8250 Egå Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail [email protected] Nyvangsvej 9 Harlev Fællesråd Arne Nielsen 8462 Harlev Herredsvej 10 Hasle Fællesråd Klaus Bendixen [email protected] 8210 Aarhus Jens Maibom Lyseng Allé 17 Holme-Højbjerg-Skåde Fællesråd [email protected] -

Socialdemokratiet I Viby Medlemsblad, Nr

Socialdemokratiet i Viby Medlemsblad, nr. 1, februar 2018 1 Socialdemokratiet i Viby Side Forside, Foråret er på vej 1 Indholdsfortegnelse og kolofon 2 Leder, formandens spalte, Ilse Klinke 3 Organisatorisk generalforsamling, indkaldelse, dagsorden, forretnings- 4-5 orden Bestyrelsesmøderne i Viby Partiforening, Ilse Klinke 5 Borgermøde om Viby Syd, referat, Ilse Klinke 6 Tak for indsatsen, Camilla Fabricius 7 Hvad skal der ske de næste fire år, Ango W inther 8-9 Min hektiske valgkamp, Ali Nuur 9 Nytårsbriefing 2018, Jacob Bundsgaard 10-11-23 Det nye regionsråd er påbegyndt arbejdet, Anders Kühnau 12 Frivillighedsåret, Flemming Knudsen 13 Konstitueringen i det nye regionsråd, Flemming Knudsen 13-9 Fremtidsforsker: Tilsandede veje vil gå ud over byens vækst, Jyllands- 14-15 Posten Vækst og jobvækst i Aarhus, Jan Beyer Schmidt-Sørensen 16 Socialdokratiets asyl-udspil, Socialdemokratiets hjemmeside 17-19 En god folkeskole for alle børn, Annette Lind 20-21 Velfærd først - ikke råd til skattelettelser, Jesper Petersen 22 Oversigt over bestyrelsen m. fl. 23 Kalender 24 Viby Partiforening udgiver medlemsbladet 3-4 gange årligt. De indsendte indlæg er ikke nødvendigvis udtryk for redaktionens holdninger. Redaktionen forbeholder sig ret til at forkorte indlæg, ligesom den forbeholder sig ret til at afvise eller udsætte indlæg til tryk- ning i et senere medlemsblad. Uden redaktionens samtykke må medlemsbladet, dele af bladet eller artikler og fotos ikke gengives. Til næste medlemsblad er der deadline ultimo maj 2018. Indlæg og artikler modtages til Ilse Klinkes mailadresse [email protected] - Håndskrevne indlæg er også velkomne og sendes til Ilse Klinke, Søndervangen 51.2. tv, 8260 Viby J. Redaktionen af dette nr.: Ilse Klinke (redaktør, korrektur, div. -

Oktober 2014 | Nr. 5 | 15. Årgang UDLEJERFORENINGEN AARHUS

Nyhedsbrev Oktober 2014 | nr. 5 | 15. årgang 4-5 | Overdragelse af lejemål 7-9 | Energisparepakken 14-15 | Åbyen - en By i Byen uden istandsættelse Luftsteg og vindfrikadeller? UDLEJERFORENINGEN AARHUS - VI VARETAGER DINE INTERESSER Kursusoversigt Nyhedsbrev Oktober 2014 | nr. 5 | 15. årgang Udlejerforeningen Aarhus’ kurser er en Nr. Titel Underviser Dato Filial af Danske Udlejeres kursusvirk- 4 Generationsskifte Hans Nielsen og Søren Lyager 20.10.14 somhed. 5 Forbrugsregnskaber Louise Kaczor, Søren Lyager og Techem 27.10.14 KURSUSBEVIS TIL LYKKE! 6 Bedre lejekontrakter Erik Aagaard Poulsen 03.11.14 Efter vore kurser udstedes deltagerbe- 7 Vedligehold og forbedringer Hans A. Nielsen og Jan Mehlsen 10.11.14 viser til alle som ønsker det. Advokater Byrådet har indgået en ny aftale om kommunens budget. 8 Lejens størrelse og regulering Søren Lyager og Louise Kaczor 17.11.14 og revisorer vil således kunne lade vore 9 Småhusejendomme Erik Aagaard Poulsen 24.11.14 kurser indgå i deres faglige forpligtel- Hvorfor siger vi som udlejerorganisation så til lykke med det? 4-5 | Overdragelse af lejemål 7-9 | Energisparepakken 14-15 | Åbyen - en By i Byen ser til kursusdeltagelse. Alle kurser er uden istandsættelse Luftsteg og vindfrikadeller? INFORMATION på 3 lektioner og giver 3 kursuspoint. Jo - Aarhus Kommune halter langt bagefter andre kommuner, når det gælder UDLEJERFORENINGEN AARHUS - VI VARETAGER DINE INTERESSER Max. deltagerantal til alle kurser: 50. AFBUD erhvervsvenlighed. Mange organisationer, os selv inklusiv, har fremført forskellige Aftenkurser starter kl. 19.00 og slutter senest kl. 22.00. Har du tilmeldt dig et kursus og senere Forsiden: Banegårdspladsen i Aarhus Festuge synspunkter og holdninger på områder, hvor der virkelig er brug for forbedringer. -

Social Capital in Gellerup

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Journal of social inclusion. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Espvall, M., Laursen, L. (2014) Social capital in Gellerup. Journal of social inclusion, 5(1): 19-42 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:miun:diva-23812 Social capital in Gellerup ___________________________________________ Line Hille Laursen Psychiatric Research Unit West Denmark Majen Espvall Mid-Sweden University Abstract This paper examines the characteristics of two types of social capital; bridging and bonding social capital among the residents inside and outside a marginalized local community in relation to five demographic features of age, gender, geographical origin and years of residence in the community and in Denmark. The data were collected through a questionnaire, conducted in the largest marginalized high-rise community in Denmark, Gellerup, which is about to undergo an extensive community renewal plan. The study showed that residents in Gellerup had access to bonding and bridging social capital inside and outside Gellerup. Nevertheless, the character of the social capital varied considerably depending on age, geographical origin and years lived in Gellerup. Young residents and people who had lived for many years in Gellerup had more social capital than their counterparts. Furthermore, residents from Arab countries had more bonding relations inside Gellerup, while residents from Northern Europe had more bonding relations outside Gellerup. Keywords: Social capital, marginalized communities, Denmark, bonding social capital, bridging social capital Journal of Social Inclusion, 5(1), 2014 Journal of Social Inclusion, 5(1), 2014 Introduction During the 1960s and 1970s, communities of large-scale high-rise housing estates were built in many countries to meet the after-war housing shortage. -

Testmuligheder I Aarhus Kommune

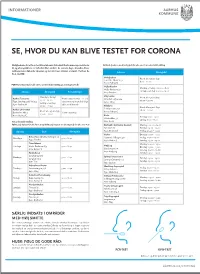

INFORMATIONER SE, HVOR DU KAN BLIVE TESTET FOR CORONA Mulighederne for at få en test bliver løbende forbedret. Der kommer nye teststeder Kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år uden tidsbestilling til, og åbningstiderne er forbedret flere steder i de seneste dage. Desuden bliver testkapaciteten løbende tilpasset og sat ind, hvor smitten er størst. Her kan du Adresse Åbningstid få et overblik: Nobelparken Åbent alle ugens dage Jens Chr. Skous Vej 2 8.00 – 20.00 8000 Aarhus C PCR-Test (I halsen) for alle over 2 år med tidsbestilling på coronaprover.dk Vejlby-Risskov Mandag – fredag: 06.00 – 18.00 Vejlby Centervej 51 Lørdag – søndag: 09.00 – 19.00 Adresse Åbningstid Bemærkninger 8240 Risskov Mandag – fredag: Viby Hallen Aarhus Testcenter Handicapparkering er på Åbent alle ugens dage 07.00 – 21.00 Skanderborgvej 224 Tyge Søndergaards Vej 953 testcentret og man skal følge 08.00 – 20.00 Lørdag – søndag: 8260 Viby J 8200 Aarhus N skiltene til kørende 08.00 – 21.00 Filmbyen Åbent alle ugens dage Aarhus Universitet Filmbyen Studie 1 Åbent alle ugens dage 08.00 – 20.00 Bartholins Allé 3 Handicapvenlig 8000 Aarhus C 09.00 – 16.00 8000 Aarhus C Beder Torsdag: 11:00 - 19:00 Kirkebakken 58 Lørdag: 11:00 - 17:00 Test uden tidsbestilling. 8330 Beder PCR test (i halsen for alle fra 2 år og kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år. Brabrand - Det Gamle Gasværk Mandag: 09.00 – 19.00 Byleddet 2C Tirsdag: 09.00 – 19.00 Ugedag Sted Åbningstid 8220 Brabrand Fredag: 09.00 – 19.00 Harlev Onsdag: 09:00 - 19:00 Beboerhuset Vest’n, Nyringen 1A Mandage 9.00 - 16.30. -

Liné RINGTVED Thordarson Sculpture

LINÉ RINGTVED THORDARSON SCULPTURE "SENSITIVITY, FRAGILITY AND STRENGTH" "Paradise tales. Liné’s new sculptures exude erotic feelings which blossom and open up. Eroticism has been a permanent feature of Liné’s works from the beginning, but it has grown in scale and expression, almost with a desire to meet the audience in an uplifting and liberating way. The sensuality has been released and has become a way of expression, which means that Liné progressively frees herself from the art historical models that have accompanied her, and instead sets up her own independent merge: Goddesses in paradise tales from the garden of sensuality. As the poet Pia Tafdrup has called it, 'a spring tide of happiness'." Erik Meistrup. Art critic and Culture editor "Joy" varnished bronze 28 cm H X "In the gallery I immediately noticed Liné’s sculpture "expectation", the figure's sensual passion seemed overwhelming from all angles. I had to take a closer look at it, bought it and brought it home. It reveals still more about more nuanced modes, perhaps a loneliness, not irreparable as it is metamorphosed into protest, will and energy in a wild vibrating power of expression. Behind lies a longing (and Longing, is what I call it myself) for something that may or may not exist – in the past or in the future. What "expectation" expresses is existential and commond to all mankind." Johan Bender. Historian and Author "Expectation" bronze 41 cm L "Zephora" (The one who is admired by many) bronze 62 cm "The virtuosity, the tecnical superiority with which she masters -

Smagen Af Æbler I Aarhus Som PDF-Fil

SMAGEN AF ÆBLER I AARHUS Smag på Aarhus, Aarhus Kommune, september 2017, revideret 2020 Foto: Anne Louise Madsen (s. 17), Cecilie Lambertsen & Stine Stampe Johansen (s. 18-27) og Aarhus Kommune www.smagpaaaarhus.dk Indhold 5 Æbler i det offentlige rum 6 Find de gode æblesteder i Aarhus 8 Spiseæbler på store gamle træer Æblehaven i Lystrup, Tilst Bypark, Marienlystparken, Frederiksbjerg Bypark, Engdalgårdsparken, Holme Bypark, Sletvej Æbleskov, Ryparken, parken ved Vil- helmsborg, Lerbjergparken, Langenæsparken, Vejlby Torv, Bomgårdshaven i Mårslet og Donbækhuse i Mindeparken 10 Spiseæbler - nye æblesteder Egå Marina, Harlev Æblelund, Vorrevangsparken, Vår- kærparken, Østerby Mose, Æblelunden Skejby, Veste- reng Æblelund, Skovvejens Æblelund, Viby Torv, Chr. Kiers Plads, Lisbjerg Skov, True Skov, Solbjerg Skov, Åbo Skov, Lillehammervej Legeplads 13 Skovæbler og vilde æbler Brabrandstien, Moesgård Strand, Gellerup skov 14 Viden om æbler 16 Modningsskema 17 Opskrifter 3 Skovvejens Æblelund Vil du også plante og passe frugttræer i dit lokalområde, så find inspiration på www.smagpaaaarhus.dk og skriv til [email protected] 4 Æbletræer i det offentlige rum Du må gerne spise æbler af træer, der står på de offentlige arealer, det vil sige langs stier, i parker og i skovene. Flere steder i Aarhus er der rigtig Aarhusianerne har også taget gode spiseæbler i parker og grønne skovlen i egen hånd – og med områder. Det er blandt andet tid- støtte fra Smag på Aarhus – plan- ligere æbleplantager eller æble- tet frugttræer i deres lokalområder haver fra gamle gårde, der på til glæde for fællesskabet. Ved grund af byudviklingen er blevet at påvirke de nære omgivelser er købt af kommunen. -

Nyt Fra Din Grundejerforening

Nyt fra din grundejerforening Medlemsblad for Aabyhøj Grundejerforening 25. årgang - april/maj 2014 FORMANDENS INDLÆG Udgiver: Forsidebillede : Årets vigtigste begivenhed indtil nu har som af Åby Park skrider godt frem. For enden Aabyhøj Grundejerforening Daugaard Pedersen A/S sædvanlig været afholdelse af den årlige af Parken – i nord såvel som i syd – er generalforsamling, som fandt sted tirsdag, der opsat informationsplancher, hvor Grafisk produktion: Antal: Trykt i 370 ekspl. by pernille granath den 18. marts 2014. Andetsteds i bladet er man kan se, hvad der kommer til at ske. www.pernillegranath.dk Ansvarshavende redaktør: der en fyldig omtale af Generalforsamlingen. Hvis man vil være opdateret på, hvad Preben Sørensen Generalforsamlingen blev i år noget af et til- forskønnelsen/renoveringen indebærer Aabyhøj Grundejerforening løbsstykke – ca. 55 var mødt frem. Måske har vil det være en god idé at lægge vejen Foreningen er en upolitisk grundejerforening, der er talerør for grundejere bosiddende i det også haft en effekt, at Elværkets status forbi parken i den nærmeste fremtid. postdistrikt 8230 Åbyhøj. og fremtid var kommet i fokus denne aften. Etableringsår Det er dejligt at kunne registrere, at der igen- Jeg vil opfordre alle til fortsat at engagere 1924 nem de seneste 2-3 år har været et stadigt sig i byens udvikling, og give sin mening Kontakt: stigende fremmøde. Vi tolker det som en til kende uanset om man er positivt stemt Personlig henvendelse: Rettes til Formanden markant opbakning til de tiltag, bestyrelsen over for de mange planer, eller har en mere Hjemmeside: www.aabyhojgrundejerforening.dk har stået bag igennem de seneste år, og på kritisk holdning desangående. -

8 PAPER 1 'Mass Housing and the Emergence of the 'Concrete Slum

PAPER 1 ‘Mass Housing and the Emergence of the ‘Concrete Slum’ in Denmark in the 1970s & 1980s’ by Mikkel Høghøj (School of Culture and Society, Aarhus University, Denmark) Abstract However, in a Danish context studies of how and why modernist mass housing developed from By investigating how modernist mass housing being emblematic of urban modernity in the 1950s was turned into both an ‘object of criticism’ and and 1960s to serving as a prime marker of societal an ‘object of study’ in the 1970s and early 1980s crisis in the 1970s and 1980s are surprisingly few – Denmark, this articles seeks to bring new perspec- especially when considering how contested these tives to the early history of Danish mass housing. places are today. The present article addresses Even though the rejection of urban modernism this research gap by examining two ways in which constitutes a well-established feld of research Danish mass housing was reappraised during internationally, surprisingly few scholars have so the 190s and 0s ore specifcall, analse far investigated how this played out in a Danish how modernist mass housing transformed as a context. This article addresses this research gap particular type of ‘place’ in Danish society by being by analysing how mass housing was portrayed turned into both an ‘object of criticism’ and an and re-evaluated as a ‘place’ in Danish mass ‘object of study’. Yet, in order to explain this trans- media and popular culture as well as within social formation, certain characteristics of the planning scientifc research from the 190s to the mid- and construction of Danish mass housing in the 1980s. -

Materialebeskrivelse Bygning C

MATERIALEBESKRIVELSE CERES PARK C CERES BYEN 46-50 8000 AARHUS C 58 EJERLEJLIGHEDER Ydermur m.v.: Designa indkalder alle købere, der har købt lejlighed inden d. 1. april Ceres Park opføres som et elementhus med bærende vægge i beton. 2018, til en gennemgang af køkkenprojektet, hvis man ønsker det. Ovenpå elementer monteres hul dækelementer. Udvendige facader Det vil være muligt at vælge alternative overflader og indretning opmures som traditionelt murværk i gule sten. Der udføres relieffelter af elementerne. Det bemærkes, at position for hvidevarer skal fast- i murværk i større felter, hvor mursten forskydes ved opmuringen. holdes af hensyn til installationer. Ekstrakøb faktureres direkte fra Fuge er gyldenbrun/grå i bakkesand. Murværk går til terræn, hvor der Designa Erhverv A/S. Efter d. 1. april 2018 vil alle køkkener blive afsluttes med sokkelklinke. Sålbænke i vinduerne er hvid beton. monteret med hvide elementer. I facaden isættes vinduer i træ/alu system. Vinduerne er med træ indvendigt og aluminium udvendigt. Indvendigt er vinduesrammer Hårde hvidevarer: fra fabrikken malet i hvid standardfarve. Udvendigt er vinduerne Der leveres følgende hvidevarer fra Siemens: flaskegrønne (Dog er tilbagetrukne vinduer på altaner hvide). Indbygningsovn ...................... HB578ACS0S Tag: Kogesektion induktion ............... EH631BEB1E Tage er flade, som beklædes med sort tagpap. Tagfladen foran Køle-/fryseskab integrerbar.......... KI87VVF30 tagterrasser beklædes med sedum (sedumplanter, mosser og urter). Opvaskemaskine integrerbar ........ SN636X04CE Kondenstørretumbler ................ WT45RVB8DN Indvendige vægge: Vaskemaskine ....................... WM14N1B8DN Bagmur udføres i betonelementer, som spartles og males hvid på filt. Indvendige gipsskeletvægge, letklinkebeton og gipsforsatsvægge Opmærksomheden henledes på, at hvidevarenumre skifter hyppigt spartles og males hvide på filt. og der vil ved indflytning antageligt være nye numre for tilsvarende modeller. -

Årbog 2018·2019

ÅRBOG 2018·2019 · INSTITUT FOR ODONTOLOGI & ORAL SUNDHED · TANDLÆGER · SIDE 1. semester · Hold A 1 1. semester · Hold B 3 1. semester · Hold C 5 1. semester · Hold D 7 1. semester · Hold E 9 3. semester · Hold A 11 3. semester · Hold B 13 3. semester · Hold C 15 3. semester · Hold D 17 5. semester · Hold A 19 5. semester · Hold B 21 5. semester · Hold C 23 5. semester · Hold D 25 7. semester · Hold A 27 7. semester · Hold B 29 7. semester · Hold C 31 7. semester · Hold D 33 9. semester · Hold A 35 9. semester · Hold B 37 9. semester · Hold C 39 9. semester · Hold D 41 Tandlæger · 1. semester · Hold A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Side #1 af #42 Nr. Navn Telefonnummer Adresse 1 Linea Thygesen Nors 31666933 Nørre Allé 28, 1.2, 8000 Aarhus 2 Mia Ngoc Hoang 26224599 Gøteborg Allé 5N, 1.33, 8200 Aarhus N 3 Pernille Jensen 4 Sofie Brøgger Lippert 29891306 Holmetoften 26, 8270 Højbjerg 5 Manizheh Yousefi 42205985 6 Rüveyda Yüce 42771234 Vestervænget 6a 1.tv., 7800 Skive 7 Markus Eriksen 21190850 Vintervej 16a th 8210 Aarhus V 8 Howraz 9 Sofia Röwekamp 23691903 Borresøvej 37, st th, Iwersen 8240 Risskov 10 Anna Kristine 30647405 Åboulevarden 51, 5 tv Haugaard Nielsen 8000 Aarhus C 11 Karoline Arnsted Lystbæk 24277477 Vilhelm Becks Vej 77, 2. tv, 8260 Viby J 12 Emely Marie Schiller 93972512 Thit Jensens gade 10 st, tv, 8000 Aarhus C 13 Johanne Holm Madsen 14 Johanne Nilsson Side #2 af #42 Tandlæger · 1. -

Urban Youth and Outdoor Spa

Architecture, Design and Conservation Danish Portal for Artistic and Scientific Research Aarhus School of Architecture // Design School Kolding // Royal Danish Academy Urban Youth & Outdoor Space in Gellerup Nielsen, Tom; Terkelsen, Katrine Duus ; Schneidermann, Nanna ; Pedersen, Leo ; Hoehne, Stefan ; Thelle, Mikkel ; Bürk, Thomas ; Nielsen, Morten Publication date: 2015 Link to publication Citation for pulished version (APA): Nielsen, T., Terkelsen, K. D., Schneidermann, N., Pedersen, L., Hoehne, S., Thelle, M., Bürk, T., & Nielsen, M. (2015). Urban Youth & Outdoor Space in Gellerup: URO LAB REPORT #1. Aarhus Universitet. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 Urban Youth & Outdoor Space in Gellerup URO LAB 1 REPORT #1 0 3 INTRODUCTION : 4 Urban orders and the