Download Proceedings 2 Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 a New Global Tide of Rising Social Protest? the Early Twenty-First Century in World Historical Perspective

A New Global Tide of Rising Social Protest? The Early Twenty-first Century in World Historical Perspective Sahan Savas Karatasli, Johns Hopkins University Sefika Kumral, Johns Hopkins University Beverly Silver, Johns Hopkins University Contact Information: Beverly J. Silver Department of Sociology The Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD 21218 [email protected] 410-516-7635 Paper presented at the Eastern Sociological Society Annual Meeting (as part of Mini-conference on Globalization in Uncertain Times) Baltimore, MD, February 22-25, 2018 (Session 216: February 24, noon-1:30 pm) 1 A New Global Tide of Rising Social Protest? The Early Twenty-first Century in World Historical Perspective I. The Problem and Its Significance A (Puzzling) Resurgence of Labor and Social Unrest: During the past three decades, there had been an almost complete consensus in the social science literature that labor movements worldwide were in a severe (many argued 'terminal') crisis (see for example, Sewell 1993; Zolberg 1995; Castells 1997; Gorz 2001). In a similar vein, the dominant position in the social movement literature was that "class" had become largely irrelevant as an organizing principle for collective action and social movement organization (see, e.g., Larana et al 1994; Pakulski and Waters 1996; for a critique see Rosenhek and Shalev 2014). In the past several years, however, there has been a growing chorus among sociologists pointing to the resurgence of labor protest in various parts of the world (see for example, Milkman 2006, Chun 2009, Silver and Zhang 2009, Agarwala 2013, Zhang 2015, Ness 2015). Likewise, beginning around 2010, major newspapers were suddenly filled with reports of labor unrest around the world, after a two decade lull in such reports (Silver 2003, 126; Silver 2014). -

Focaal Forums - Virtual Issue

FOCAAL FORUMS - VIRTUAL ISSUE Managing Editor: Luisa Steur, University of Copenhagen Editors: Don Kalb, Central European University and Utrecht University Christopher Krupa, University of Toronto Mathijs Pelkmans, London School of Economics Oscar Salemink, University of Copenhagen Gavin Smith, University of Toronto Oane Visser, Institute of Social Studies, The Hague A regular feature of Focaal is its Forum section. The Forum features assertive, provocative, and idiosyncratic forms of writing and publishing that do not fit the usual format or style of a research-based article in a regular anthropology journal. Forum contributions can be stand-alone pieces or come in the form of theme-focused collection or discussion. Introducing: www.FocaalBlog.com, which aims to accelerate and intensify anthropological conversations beyond what a regular academic journal can do, and to make them more widely, globally, and swiftly available. _________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Number 69: Mavericks Mavericks: Harvey, Graeber, and the reunification of anarchism and Marxism in world anthropology by Don Kalb II. Number 66: Forging the Urban Commons Transformative cities: A response to Narotzky, Collins, and Bertho by Ida Susser and Stéphane Tonnelat What kind of commons are the urban commons? by Susana Narotzky The urban public sector as commons: Response to Susser and Tonnelat by Jane Collins Urban commons and urban struggles by Alain Bertho Transformative cities: The three urban commons by Ida Susser and Stéphane Tonnelat III. Number 62: What makes our projects anthropological? Civilizational analysis for beginners by Chris Hann IV. Number 61: Wal-Mart, American consumer citizenship, and the 2008 recession Wal-Mart, American consumer citizenship, and the 2008 recession by Jane Collins V. -

A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 by Peter T

A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 By Peter T. Humphrey A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor James Q. Davies, Chair Professor Nicholas de Monchaux Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Nicholas Mathew Spring 2021 Abstract A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 by Peter T. Humphrey Doctor of Philosophy in Music and the Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor James Q. Davies, Chair This dissertation argues that a cinematic approach to music recording developed during the 1950s, modeling the recording process of movie producers in post-production studios. This approach to recorded sound constructed an imaginary listener consisting of a blank perceptual space, whose sonic-auditory experience could be controlled through electroacoustic devices. This history provides an audiovisual genealogy for electroacoustic sound that challenges histories of recording that have privileged Thomas Edison’s 1877 phonograph and the recording industry it generated. It is elucidated through a consideration of the use of electroacoustic technologies for music that centered in Hollywood and drew upon sound recording practices from the movie industry. This consideration is undertaken through research in three technologies that underwent significant development in the 1950s: the recording studio, the mixing board, and the synthesizer. The 1956 Capitol Records Studio in Hollywood was the first purpose-built recording studio to be modelled on sound stages from the neighboring film lots. The mixing board was the paradigmatic tool of the recording studio, a central interface from which to direct and shape sound. -

Avhandling-340-Fagerlid-Materie.Pdf (1.290Mb)

The Stage is all the World, and the Players are mere Men and Women Performance Poetry in Postcolonial Paris Cicilie Fagerlid Dissertation submitted for the partial fulfilment of the Ph.D. degree, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Oslo, January 2012 © Cicilie Fagerlid, 2012 Series of dissertations submitted to the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Oslo No. 340 ISSN 1504-3991 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. Cover: Inger Sandved Anfinsen. Printed in Norway: AIT Oslo AS. Produced in co-operation with Unipub, Oslo. The thesis is produced by Unipub merely in connection with the thesis defence. Kindly direct all inquiries regarding the thesis to the copyright holder or the unit which grants the doctorate. &#" From the very beginning, this research project has taken place in a strange zone between life and death, regeneration and destruction. It has been carried out in warm memory of Anita Jarl and her little son Julian whose sudden death, less than a week before I took up the long awaited and long wished for PhD position, brought a sadness into my life that I had not yet known, and in memory of Professor Eduardo Archetti who fell seriously ill at the same time. The exuberant guardian father at the Department of Social Anthropology in Oslo was meant to be my supervisor. I am forever grateful for the advice that he found time to give me, and even more for having the opportunity to experience – the last years of his career and the first years of mine – the personal and professional warmth that he radiated. -

UWM Libraries Digital Collections

Concert review: pg 13 David Byrne returns to Milwaukee uwMrOSl The Student-Run Independent Newspaper at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee The potential presidencies of V Obama and McCain compared Controversy over News pg 5 bookstore sweatshop allegations RunUp the Runway showcases local fashion designers Robert Spencer, founder of Jihad Watch, speaking Thursday evening in at MAM Bolton Hall. Post photo by Alana Soehartono Concert Reviews: Spencer lecture lacked Minus the Bear Mountain Goats outbursts, interruptions Man Man David Byrne Extensive Freedom Center is a conserva SDS claims stem from Bookstore, SDS approached the tive organization founded by UWM's refusal to join Brand Standards Committee security prevents Horowitz, who was the subject fringe pg 7 with a request that UWM reject of a controversial visit to UWM DSP program their support of two groups used Horowitz repeat this past spring. to assure all logo sale items are Prior to entering the lecture Women's soccer By Cordelia Ellis manufactured in a sweatshop By Jo Rey Lopez and Kevin Lessmiller hail, attendees had to endure an Special to The Post free environment with equal airport-like security screening, breaks season worker rights. With enough security to complete with a walk-through goal record The UW-Milwaukee Students SDS requested that UWM join quell a small riot, conservative metal detector, bag and purse for a Democratic Society (SDS) the Designated Supplier Program speaker Robert Spencer took the search, followed by another recently launched an anti-sweat (DSP), a proposed new system by stage in UW-Milwaukee's Bolton screening by a handheld metal "Kicks for Hoops" shop campaign, which claims WRC. -

(Khartoum, Soudan) Et Caño De Loro (Carthagène, Colombie). Histoire, Localité Et Politique Dans Une Perspective D’Anthropologie Urbaine Comparée

Université de Paris 8 École doctorale de Sciences Sociales – 401 Laboratoire Architecture, Ville, Urbanisme et Environnement UMR 7218 THESE DE DOCTORAT Discipline : Anthropologie Ethnographies de la gestion de l’eau à Tuti (Khartoum, Soudan) et Caño de Loro (Carthagène, Colombie). Histoire, localité et politique dans une perspective d’anthropologie urbaine comparée. Luisa ARANGO Thèse dirigée par Barbara CASCIARRI Soutenue le 27 novembre 2015 Jury : Habib AYEB, Maître de Conférences en Géographie (HDR) à l’Université Paris 8. Alain BERTHO, Professeur d’Anthropologie à l’Université Paris 8. David BLANCHON, Professeur de Géographie à l’Université Paris Ouest-Nanterre. Barbara CASCIARRI, Maître de Conférences en Anthropologie (HDR) à l’Université Paris 8. Eric DENIS, Géographe, Directeur de recherche au CNRS. Aline HEMOND, Professeure d’Anthropologie à l’Université de Picardie Jules Verne. Mauro VAN AKEN, Professeur d’Anthropologie à l’Université de Milano-Bicocca. A la mémoire de mon ami Miguel Felipe Morelos Castillo (1917-2008) A su picó “El Gran Pepe” à ses enfants et petits enfants. 2 Remerciements Si le présent travail est le résultat d’un long cheminement intellectuel, ce parcours, avec ces joies et ses dangers, ses certitudes et ses doutes, n’aurait pu aboutir sans le soutien et l’amitié de nombreuses personnes. Je tiens à leur exprimer ma plus sincère gratitude. Je voudrais d’abord remercier les personnes qui sont au centre de cette recherche : les habitants de Caño de Loro et de Tuti qui m’ont accueillie et orientée avec patience – et souvent avec beaucoup d’humour – sur les chemins fluides de l’eau et de son partage. -

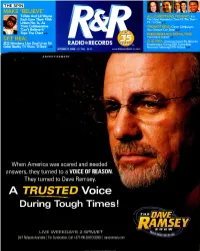

A TRUSTED Voice

THE SPIN MAKE 'BELIEVE' T Pain And LiI Wayne A MAS FORMAT: It's Each Earn Their Fifth The Most Wonderful Time Of The Year - Urban No. ls, As Til -'s Over Their Collaborative PROMOTIONS: Clever Campaigns 'Can't Believe It' You Station Can Steal Tops The Chart PERFORMANCE ROYALTIES: The Global Ir,pact GET ; THE PPM: Concerns Raised By Minority 302 Members Live Dual Lives On RADIO & RECORDS Broadcasters During R &R Conve -rtion Cable Reality TV Show 'Z Rock' Resonate Following PPM Rollout OCTOBER 17, 2008 NO. 1784 $6.EO www.RadioandRecc -c s.com ADVERTISEMENT When America was scared and needed nswers, they turned to a VOICE OF REASON. They turned to Dave Ramsey. A TRUSTED Voice During Tough Times! 7 /THEDAVÊ7 C AN'S HOW Ey LIVE WEEKDAYS 2-5PM/ET 0?e%% aáens caller aller cal\e 24/7 Re-eeds Ava lable For Syndication, Call 1- 877 -410 -DAVE (32g3) daveramsey.com www.americanradiohistory.com National media appearances When America was scared and needed focused on the economic crisis: answers, they turned to a voice Your World with Neil Cavuto (5x) of reason. They turned to Dave Ramsey. Fox Business' Happy Hour (3x) The O'Reilly Factor Fox Business with Dagen McDowell and Brian Sullivan Fox Business with Stuart Varney (5x) Fox Business' Bulls & Bears (2x) America's Nightly Scoreboard (2x) Larry King Live (3x) Fox & Friends (7x) Geraldo at Large (2x) Good Morning America (3x) Nightline The Early Show Huckabee The Morning Show with Mike and Juliet (3x) Money for Breakfast Glenn Beck Rick & Bubba (3x) The Phil Valentine Show and serving our local affiliates: WGST Atlanta - Randy Cook KTRH Houston - Michael Berry KEX Portland - The Morning Update with Paul Linnman WWTN Nashville - Ralph Bristol KTRH Houston - Morning News with Lana Hughes and J.P. -

Introduction: Interpreting the Global Economy Through Local Anger

IRSH (), pp. – doi:./S © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Introduction: Interpreting the Global Economy through Local Anger L EYLA D AKHLI Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Centre Marc Bloch Friedrichstraße Berlin, Germany E-mail: [email protected] V INCENT B ONNECASE Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Institut des mondes africains cours des Humanités Aubervilliers, France E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: During the s and s, violent events occurred in the streets of many African and Middle Eastern countries. Each event had its own logic and saw the inter- vention of actors with differing profiles. What they had in common was that they all took place in the context of the implementation of a neoliberal political economy. The anger these policies aroused was first expressed by people who were not necessarily rebelling against the adjustments themselves, or against the underlying ideologies or the institutions that imposed them, but rather against their practical manifestations in everyday life. This special issue invites reflections on these revolts and what they teach us about the neoliberal turn in Africa and the Middle East. The echoes between the present and the recent past are as important for the genesis of this work as they are for those that read it. -

Une Discographie De Robert Wyatt

Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Discographie au 1er mars 2021 ARCHIVE 1 Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Ce présent document PDF est une copie au 1er mars 2021 de la rubrique « Discographie » du site dédié à Robert Wyatt disco-robertwyatt.com. Il est mis à la libre disposition de tous ceux qui souhaitent conserver une trace de ce travail sur leur propre ordinateur. Ce fichier sera périodiquement mis à jour pour tenir compte des nouvelles entrées. La rubrique « Interviews et articles » fera également l’objet d’une prochaine archive au format PDF. _________________________________________________________________ La photo de couverture est d’Alessandro Achilli et l’illustration d’Alfreda Benge. HOME INDEX POCHETTES ABECEDAIRE Les années Before | Soft Machine | Matching Mole | Solo | With Friends | Samples | Compilations | V.A. | Bootlegs | Reprises | The Wilde Flowers - Impotence (69) [H. Hopper/R. Wyatt] - Robert Wyatt - drums and - Those Words They Say (66) voice [H. Hopper] - Memories (66) [H. Hopper] - Hugh Hopper - bass guitar - Don't Try To Change Me (65) - Pye Hastings - guitar [H. Hopper + G. Flight & R. Wyatt - Brian Hopper guitar, voice, (words - second and third verses)] alto saxophone - Parchman Farm (65) [B. White] - Richard Coughlan - drums - Almost Grown (65) [C. Berry] - Graham Flight - voice - She's Gone (65) [K. Ayers] - Richard Sinclair - guitar - Slow Walkin' Talk (65) [B. Hopper] - Kevin Ayers - voice - He's Bad For You (65) [R. Wyatt] > Zoom - Dave Lawrence - voice, guitar, - It's What I Feel (A Certain Kind) (65) bass guitar [H. Hopper] - Bob Gilleson - drums - Memories (Instrumental) (66) - Mike Ratledge - piano, organ, [H. Hopper] flute. - Never Leave Me (66) [H. -

Levasseur10phd.Pdf

ESSAI DE LECTURE «DEMOCRATIQUE» DES REPRESENTATIONS CULTURELLES DES GRANDS ENSEMBLES FRANÇAIS: UNE «ARCHIVE» DE LA CITE DES QUATRE-MILLE A LA COURNEUVE (1962-2002) One volume and one archive by BRUNO LEVASSEUR A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of French Studies College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ii Résumé: Cette thèse s’assigne comme objectif primordial d’examiner l’évolution des évocations culturelles et théoriques des grands ensembles français et de montrer, par une approche multidisciplinaire combinant histoire, philosophie, sociologie et culture, les enjeux d’une lecture «démocratique» des représentations des cités au sein de la France contemporaine. Partant du postulat selon lequel la circulation des discours sur les marginalités a été façonnée, policée et relayée par les grands supports de communication affiliés à la culture de masse, cette étude vise à soumettre un examen décentré de la dynamique relationnelle entre les cités périphériques et la communauté nationale durant ces dernières décennies. Nous proposons que le concept de «démocratie» informé par le travail philosophique de Jacques Rancière permet un examen original des modes de représentations des périphéries au sein de la culture populaire de ces quarante dernières années. -

Extensions of Remarks Hon. Harold T. Johnson

January 6, 1969 '.EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 247 REPORT OF TELLERS of the United States, as delivered to the 2228, New Senate Office Building, before Mr. CURTIS. Mr. President, on behalf President of the Senate, is as follows: the Committee on the Judiciary, on John of the tellers on the part of the Senate, The whole number of electors ap N. Mitchell, of New York, Attorney Gen I wish to report on the counting of the pointed to vote for Vice President of the eral-designate. vote for President and Vice President. United States is 538, of which a majority At the indicated time and place per The state of the vote for President of is 270. sons interested in the hearing may make the United States, as delivered to the SPIRO T. AGNEW, of the State of Mary such representations as may be pertinent. President of the Senate, is as follows: land, has received for Vice President of The whole number of electors ap the United States 301 votes. EDMUND s. MUSKIE, of the State of ADJOURNMENT UNTIL THURSDAY, pointed to vote for President of the JANUARY 9, 1969 United States is 538, of which a majority Maine, has received 191 votes. Curtis E. LeMay, of the State of Cali Mr. KENNEDY. Mr. President, if there is 270. fornia, has received 46 votes. is no further business to come before the Richard M. Nixon, of the State of New Senate, I move, in accordance with the York, has received for President of the previous order, that the Senate stand in United States 301 votes. -

2008/08/02 Tears of Rain / Charlie Haden & Pat Metheny

2008/08/02 Tears of Rain / Charlie Haden & Pat Metheny Beyond The Missouri Sky Doina, Parov's Daichevo / Tony McManus unreleased track Hard Love / Martin Simpson Live Go To The Mardi Gras / Jon Cleary Live - Mo' Hippa Buzz Buzz Buzz / The Hollywood Flames The Doo Wop Box Harlem Shuffle / Bob & Earl Land of 1000 Dances Walking In Memphis / Marc Cohn Marc Cohn Let Me Be Your Witness / Marc Cohn Join The Parade Astral Weeks / Van Morrison Astral Weeks The Way Young Lovers Do / Van Morrison Astral Weeks Come Running / Van Morrison Moondance Crazy Love / Van Morrison Moondance Domino / Van Morrison His Band And The Street Choir If I Ever Needed Someone / Van Morrison His Band And The Street Choir Johnny Cash / Ry Cooder I, Flathead 5000 Country Music Songs / Ry Cooder I, Flathead Sliding Home / Cindy Cashdollar Slide Show 2008/08/09 I Wanna Dance With Somebody / David Byrne Live from Austin TX Them Changes / King Curtis Aretha Franklin & KIng Curtis Live at Fillmore West - Don't Fight The Feeling Com' By H'Yere-Good Lord / Nina Simone It Is Finished Funkier Than A Mosquito's Tweeter / Nina Simone It Is Finished I Smell Trouble / Ike & Tina Turner Soul To Soul In The Midnight Hour / Wilson Pickett A Man And A Half Bring It On Home To Me~Nothing Can Change This Love / Sam Cooke live at Harlem Square Club - 1963 Louisiana / John Boutte live at Jazz Fest 2007 Mother, Mother / Allen Toussaint live at Jazz Fest 2007 Engingilaye & Te Dikalo / Richard Bona Bona Makes You Sweat - Live That's What A Little Dream Can Do / Amos Garrett Off The Floor Live! Inori / Pat Metheny w.