The Spatial Distribution of Manufacturing Industries: an Analysis of Central Java

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Situation Update Response to COVID-19 in Indonesia As of 18 January 2021

Situation Update Response to COVID-19 in Indonesia As of 18 January 2021 As of 18 January, the Indonesian Government has announced 917,015 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in all 34 provinces in Indonesia, with 144,798 active cases, 26,282 deaths, and 745,935 people that have recovered from the illness. The government has also reported 77,579 suspected cases. The number of confirmed daily positive cases of COVID-19 in Indonesia reached a new high during four consecutive days on 13-16 January since the first positive coronavirus case was announced by the Government in early March 2020. Total daily numbers were 11,278 confirmed cases on 13 January, 11,557 cases on 14 January, 12,818 cases on 15 January, and 14,224 cases on 16 January. The Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) has declared the COVID-19 Vaccine by Sinovac as halal. The declaration was stipulated in a fatwa that was issued on 8 January. On 11 January, the Food and Drug Administration (BPOM) issued the emergency use authorization for the vaccine. Following these two decisions, the COVID-19 vaccination program in Indonesia began on 13 January, with the President of the Republic of Indonesia being first to be vaccinated. To control the increase in the number of cases of COVID-19, the Government has imposed restrictions on community activities from January 11 to 25. The restrictions are carried out for areas in Java and Bali that meet predetermined parameters, namely rates of deaths, recovered cases, active cases and hospitals occupancy. The regions are determined by the governors in seven provinces: 1. -

Daftar Rumah Sakit Lini Se-Jateng

DAFTAR RUMAH SAKIT LINI SE-JATENG RUMAH SAKIT LINI I NO NAMA RUMAH SAKIT ALAMAT RUMAH SAKIT NO TELP RUMAH SAKIT 1 3 5 6 1. Direktur RSUP Kariadi Semarang Jl. Dr. Sutomo No. 16 (024) 8413476 Semarang 2. Direktur RSUD Dr. Soeradji Tirtonegoro Jl. KRT dr Soeradji Klaten Tirtonegoro No. 1 Tegalyoso, (024) 321020 Klaten 57424 3. Direktur RS Paru Dr. Ario Wiryawan Jl. Hasanudin No. 806, Mangunsari, Kec. Sidomukti (0298) 326130 Salatiga 50721 4. Direktur RSUD Kraton Kabupaten Jl. Veteran No. 31 Pekalongan Pekalongan, Kota Pekalongan (0285) 423225 51117 5. Direktur RSUD Dr. Soesilo Slawi Jl. DR. Soetomo No. 63, Slawi Kabupaten Tegal Kulon Kec. Slawi Tegal 52419 (0283) 491016 6. Plt. Direktur RSUD Dr. H. Soewondo Jl. Laut No. 21 Kendal 51311 (0294) 381433 Kendal 7. Plt. Direktur RSUD Tidar Kota Jl. Tidar No. 30A, Kemirirejo, Magelang Kec. Magelang Tengah Kota (0293) 362463 Magelang 56125 8. Direktur RSUD Moewardi Surakarta Bu Jl. Kolonel Sutarto Kec. (0271) 634634 Jebres Kota Surakarta 57126 9. Direktur RSUD Banyumas Jl. Rumah Sakit No. 1, Karangpucung, Kejawar, Kec. (0281) 796182 Banyumas Kab. Banyumas 53192 10. Direktur RSUD Dr.Loek Monohadi Jl. Dr. Lukmonohadi No. 19, Kudus Cobowo, Ploso, Kec. Jati Kab. (0291) 444001 Kudus 59348 11. Direktur RSUD Prov. Dr. Margono Jl Dr. Gumbreg No 1 Soekarjo Kebuntebu Berkoh Kec. (0281) 632708 Purwokerto Sel. Kab Banyumas 12. Direktur RSUD KRMT Wongsonegoro Jl Fatmawati no 1 Kota Semarang Mangunharjo kec. Tembalang kota Semarang 50272 (024) 6711500 NO NAMA RUMAH SAKIT ALAMAT RUMAH SAKIT NO TELP RUMAH SAKIT 1 3 5 6 13. Plt. -

“Together Picket”: Community Activities in Dengue Source Reduction in Purwokerto City, Central Java, Indonesia

Case Study 7 “Together Picket”: Community Activities in Dengue Source Reduction in Purwokerto City, Central Java, Indonesia Rita Kusriastuti*#, Thomas Suroso* Sustriayu Nalim** and Wibowo Kusumadi*** *Directorate General Communicable Disease Control and Environmental Health, Ministry of Health, Jalan Percetakan Negara No. 29, Jakarta, 10560, Indonesia **Vector Control Research Unit, Ngawen, Salatiga, Central Java, Indonesia ***Hospital Elisabeth, Purwokerto, Central Java, Indonesia Abstract This paper looks at how dengue prevention and control in Indonesia has evolved from a vertical, government-controlled programme to a more horizontal, community-based approach. The authors illustrate how social mobilization has improved Aedes source reduction by drawing upon recent experiences in Purwokerto City, Central Java. Keywords: Dengue, prevention and control, community-based, social mobilization, source reduction, Indonesia. Country setting and humidity favour mosquito populations with a peak in mosquito abundance in the rainy background season. The major dengue vector in urban The Indonesian archipelago consists of five areas is Aedes aegypti but Aedes albopticus large islands – Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan, is also present. The majority of houses in Sulawesi, and Papua – and thousands of Indonesia have a cement water container smaller islands. Approximately 60% of located in the bathroom to store water for Indonesia’s 210 million people live on Java bathing, and a smaller container in the island. There are 370 ethnic groups with 67 water closet (WC). Water containers made languages, but Bahasa Indonesia unites all from clay or plastic barrels/jars are also kept citizens. The national economy is based on in the kitchen for cooking or drinking agriculture and industrial production of the purposes. -

Walikota Salatiga Provinsi Jawa Tengah

1 WALIKOTA SALATIGA PROVINSI JAWA TENGAH PERATURAN DAERAH KOTA SALATIGA NOMOR TENTANG RENCANA DETAIL TATA RUANG BWP PK, I, II, III DAN IV KOTA SALATIGA TAHUN 2017-2030 DENGAN RAHMAT TUHAN YANG MAHA ESA WALIKOTA SALATIGA, Menimbang : bahwa untuk melaksanakan ketentuan Pasal 17 Peraturan Daerah Kota Salatiga Nomor 4 Tahun 2011 tentang Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Kota Salatiga Tahun 2010- 2030 perlu menetapkan Peraturan Daerah tentang Rencana Detail Tata Ruang BWP PK, I, II, III dan IV Kota Salatiga Tahun 2017-2030; Mengingat : 1. Pasal 18 ayat (6) Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1945; 2. Undang-Undang Nomor 17 Tahun 1950 tentang Pembentukan Daerah-daerah Kota Kecil dalam Lingkungan Propinsi Jawa Timur, Jawa Tengah dan Jawa Barat; 3. Undang-Undang Nomor 26 Tahun 2007 tentang Penataan Ruang (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2007 Nomor 68, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 4725); 4. Undang-Undang Nomor 12 Tahun 2011 tentang Pembentukan Peraturan Perundang-undangan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2011 Nomor 82, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5234); 5. Undang-Undang Nomor 23 Tahun 2014 tentang Pemerintahan Daerah (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2014 Nomor 244, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5587), sebagaimana telah diubah beberapa kali terakhir dengan Undang-Undang Nomor 9 Tahun 2015 tentang 2 Perubahan Kedua atas Undang-Undang Nomor 23 Tahun 2014 tentang Pemerintahan Daerah (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2015 Nomor 58, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5679); 6. Peraturan Pemerintah Nomor 69 Tahun 1992 tentang Perubahan Batas Wilayah Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Salatiga dan Kabupaten Daerah Tingkat II Semarang (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1992 Nomor 114, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 3500); 7. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 06:19:11PM Via Free Access 904 Chapter Nineteen

CHAPTER NINETEEN CHINESE CHRISTIAN COMMUNITIES IN INDONESIA Chinese Christians are found all over the vast Indonesian archipelago: from strongly Muslim Aceh in the west to the mixed Muslim-Christian society of the Moluccas, in the outspoken Protestant Minahasa as well as in dominant Catholic Flores. In this chapter we will mostly concentrate on the distinct Chinese Protestant churches of Java, with additional notes about the pres- ence of Catholic Chinese in Java. For areas outside Java we add comparative notes, stressing the discrepancy between the Chinese majority communities of West Indonesia as diff erent from the much smaller groups in East Indonesia. Christianity in Indonesia has only in a few places (West Kalimantan, the islands of the Riau archipelago) a dominant Chinese face, but in most regions where the Christians are a minority, the Chinese are a signifi cant segment of this community. Th is also has strengthened the idea of Christians in Indonesia as somewhat richer than the average Indonesian, because of the larger number of rich people among the Chinese in general and also among the Christian Chinese. Although a Chinese ethnic identity cannot be concealed, and ethnic- ity remains a very important factor in Indonesian society, there never was a development towards a truly contextual Chinese Christianity because church leaders did not like to stress this identity. Javanese Chinese: from integration into a Muslim society to the preservation of an distinct culture Relations of trade and partly also of religion have for a very long time been established between China and Indonesia. In the cultural and religious fi eld Indonesia has been the receiver (as was also the case with infl uence from India and the Middle East). -

57 Tahun 2005 Tentang Penetapan Tarif Batas Atas Dan Batas Bawah Angkutan Penumpang Antar Kota Dalam Propinsi Dengan Mobil Bus Umum Kelas Ekonomi Di Jalan;

PERATURAN GUBERNUR JAWA TENGAH NOMOR : 57 TAHUN 2005 TENTANG PENETAPAN TARIF BATAS ATAS DAN TARIF BATAS BAWAH ANGKUTAN PENUMPANG ANTAR KOTA DALAM PROPINSI DENGAN MOBIL BUS UMUM KELAS EKONOMI DI PROPINSI JAWA TENGAH GUBERNUR JAWA TENGAH, y. Menimbang : a. bahwa tarif penyelenggaraan Angkutan Antar Kota Dalam Propinsi Dengan Mobil Bus Umum Kelas Ekonomi sebagaimana ditetapkan dengan Keputusan Gubernur Jawa Tengah Nomor 550 / 12 / 2005 tanggal 1 Maret 2005 tentang Penetapan Tarif Batas Atas Dan Batas Bawah Angkutan Penumpang Antar Kota Dalam Propinsi Kelas Ekonomi Di Jalan Dengan Mobil Bus Umum Di Propinsi JawaTengah sudah tidak sesuai lagi dengan perkembangan keadaan; b. bahwa berdasarkan pertimbangan sebagaimana dimaksud huruf a dan sesuai Peraturan Presiden Nomor 55 Tahun 2005 tentang Harga Eceran Bahan Bakar Minyak dan Peraturan Menteri Perhubungan Nomor KM. 59 Tahun 2005 tentang Tarif Dasar Batas Atas dan Batas Bawah Angkutan Penumpang Antar Kota Antar Propinsi Kelas Ekonomi Di Jalan Dengan Mobil Bus Umum, perlu menetapkan Peraturan Gubernur tentang Penetapan Tarif Batas Atas Dan Tarif Batas Bawah Angkutan Penumpang Antar Kota Dalam Propinsi Dengan Mobil Bus Umum Kelas Ekonomi Di Propinsi Jawa Tengah; Mengingat : 1. Undang-Undang Nomor 10 Tahun 1950 tentang Pembentukan Propinsi JawaTengah; 2. Undang-Undang Nomor 14 Tahun 1992 tentang Lalu Lintas dan Angkutan Jalan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1992 Nomor 49, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 3480); 2 3. Undang-Undang Nomor 32 Tahun 2004 tentang Pemerintahan Daerah (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2004 Nomor 125, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 4437) sebagaimana telah diubah dengan Peraturan Pemerintah Penganti Undang-Undang Nomor 3 Tahun 2005 tentang Perubahan Atas Undang-Undang Nomor 32 Tahun 2004 tentang Pemerintahan Daerah (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2005 Nomor 38, Tanmbahan Lembaran Republik Indobnesia Nomor 4493); 4. -

Potensi Dan Pengembangan Kampung Etnik Arab Sebagai Aset Wisata Di Kota Surakarta

Potensi dan pengembangan kampung etnik Arab sebagai aset wisata di kota Surakarta LAPORAN TUGAS AKHIR Diajukan Untuk Memenuhi sebagian Persyaratan Memperoleh Gelar Ahli Madya Pada Program Study Diploma III Usaha Perjalanan Wisata Oleh: Fajar Endang Hastuti NIM C 9405020 FAKULTAS SASTRA DAN SENI RUPA UNIVERSITAS SEBELAS MARET SURAKARTA 2008 HALAMAN PENGESAHAN PEMBIMBING Judul Laporan Tugas Akhir : POTENSI DAN PENGEMBANGAN KAMPUNG ETNIK ARAB SEBAGAI ASET WISATA DI KOTA SURAKARTA Nama Mahasiswa : Fajar Endang Hastuti NIM : C 9405020 MENYETUJUI Disetujui Tanggal: Disetujui Tanggal: Pembimbing I Pembimbing II Dra. Sri Wahyuningsih, M. Hum Drs. Tundjung Wahadi Sutirto, M. Si LEMBAR PENSESAHAN UJIAN Judul Tugas Akhir : POTENSI DAN PENGEMBANGAN KAMPUNG ETNIK ARAB SEBAGAI ASET WISATA DI KOTA SURAKARTA Nama : Fajar Endang Hastuti NIM : C 9405020 Tanggal Ujian : 28 Juli 2008 DITERIMA DAN DISETUJUI OLEH PANITIA PENGUJI TUGAS AKHIR D III USAHA PERJALANAN WISATA FAKULTAS SASTRA DAN SENI RUPA Drs. Suharyana, M. Pd (…………………..) Ketua Ummi Yulianti, M.Hum (…………………..) Sekretaris Dra. Sri Wahyuningsih, M. Hum (…………………..) Penguji I Drs. Tundjung Wahadi Sutirto, M. Si (…………………..) Penguji II Surakarta, Agustus 2008 Dekan Drs. Sudarno, MA NIP. 131 472 202 MOTTO v Keberhasilan tidak diukur dengan apa yang telah diraih, namun diukur dengan kegagalan yang telah kita hadapi, dan keberanian yang membuat kita tetap berjuang melawan rintangan yang bertubi-tubi. (Penulis) v Rahasia terbesar dalam hidup ini adalah melewati hari ini dengan penuh makna. Makna tentang cinta, ilmu, dan iman. Dengan cinta hidup menjadi indah. Dengan ilmu hidup menjadi mudah. Dan dengan iman hidup menjadi terarah. (Untitle) v “Selemah-lemah manusia ialah orang yg tak mau mencari sahabat dan orang yang lebih lemah dari itu ialah orang yg mensia-siakan sahabat yg telah dicari”. -

Pola Proses Membangun Kapabilitas Inovasi

EKO-REGIONAL, Vol.11, No.1, Maret 2016 PENGARUH BELANJA MODAL DAN INVESTASI TERHADAP PEMBANGUNAN EKONOMI KABUPATEN/KOTA DI PROVINSI JAWA TENGAH Oleh: Hendri Panggayuh1) 1) SMA Negeri 1 Teweh Timur, Barito Utara Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Economic development is currently influenced by the internal policies of local governments, such as the large proportion of government expenditure allocated. In order to compensate for the performance of economic development, hence the need for the role of government and the private sector need to be improved, where investment as one of the alternatives in order to achieve the economic development. How big is the minimal requirements and the extent of correlation with indicators of successful economic development as the human development index, the economic growth rate, per capita income, poverty, and the open unemployment rate. The aims of this research are to determine the development of the human development index, the rate of population growth, per capita income, poverty, and the open unemployment rate, determine the effect of capital expenditure and investment towards human development index, the economic growth rate, income per capita, the poor, and the open unemployment rate. The analytical method used to test the hypothesis is boxplot analysis, cluster analysis and regression analysis. Based on the research, it is known that there are three classes in the economic development in Central Java province, of which the first class to have a common index of human development, and the growth rate of economics are in Cilacap district, Magelang City, Surakarta, Semarang and City Pekalongan. Grades two to have similar levels of percentage of the poor and the jobless rate was in Banyumas, Purbalingga, Banjarnegara, Kebumen, Purworejo, Wonosobo, Magelang, Boyolali, Klaten, Sukoharjo, Wonogiri, Karanganyar, Sragen, Grobogan, Blora, Rembang, Pati, Jepara, Demak, Semarang, Temanggung, Kendal, Batang, Pekalongan, Pemalang, Tegal, Brebes, Salatiga, Tegal. -

Bab I Pendahuluan

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Masalah Kota Surakarta yang dikenal juga Kota Solo, secara geografis memiliki luas wilayah 44km², terletak pada ketinggian ± 92 di atas permukaan laut. Dengan jumlah penduduk 514.171 terdiri dari 249.978 penduduk laki-laki (48%) dan 264.193 penduduk perempuan (52%). Kota ini terbagi dalam lima wilayah kecamatan, yaitu kecamatan Laweyan, Serengan, Pasar Kliwon, Jebres dan Banjarsari. Kota Surakarta merupakan salah satu kota besar di Jawa Tengah, berbatasan dengan Kabupaten Karanganyar dan Kabupaten Boyolali di sebelah utara, Kabupaten Karanganyar dan Kabupaten Sukoharjo di sebelah timur dan barat, dan Kabupaten Sukoharjo di sebelah selatan. Berada di antara gunung Merapi, Merbabu, dan Lawu, serta dibatasi oleh Sungai Bengawan Solo dan dibelah oleh Kali Pepe. Sejarah Kota Solo dimulai dari kepindahan ibukota kerajaan Mataram Kartasura beserta keratonnya ke desa Sala, untuk menggantikan kerajaanya di Kartasura yang hancur karena pemberontakan Sunan Kuning. Sunan Pakubuwana II membeli tanah tersebut dari Kyai Sala sebesar 10.000 ringgit (gulden Belanda). Secara resmi keraton Surakarta Hadiningrat mulai ditempati tanggal 17 Februari 1745 dan meliputi wilayah Solo Raya dan Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta modern. Kemudian sebagai akibat dari Perjanjian Giyanti (13 Februari 1755) Kerajaan Mataram SIlam dibagi menjadi 2 yaitu Yogyakarta (Hamengkubuwono I) dan Surakarta (Pakubuwono III) dan Perjanjian Salatiga (17 Maret 1757) terjadi perpecahan wilayah kerajaan, dibagi menjadi 3 yaitu Kesultanan Yogyakarta, Solo berdiri dua Kerajaan: Kasunan Surakarta dan Mangkunegaran. Keraton Kasunanan Surakarta merupakan salah satu bangunan yang eksotis di zamannya. Salah satu arsitek istana ini adalah Pangeran Mangkubumi (kelak bergelar Sultan Hamengkubuwono I) yang juga menjadi arsitek utama keraton Yogyakarta. Dibangun secara bertahap dengan mempertahankan pola 1 2 dasar tata ruang yang tetap sama dengan awalnya. -

A a Tentai\G Kerjasama Dalam

a r ; NASKAH KERJASAMA ANTARA FAKULTAS SYARI'AH a INSTITUT AGA}IA ISLAM NEGERI a PURWOKERTO DENGAN L+,SRLRT16A FAKULTAS SYARIAH INSTITUT AGAIT{A ISLAM NEGERI SALATIGA A TENTAI\G KERJASAMA DALAM MELAKSANAKAN TRI DHARJVTA PERGURUAN TINGGI FAKULTAS SYARI'AH INSTITUT AGAMA ISLAM NEGERI (rArN) PURWOKERTO FAKULTAS SYARIAH INSTITUT AGAMA ISLAM I\IEGERI (IAIN) a SALATIGA A 2017 A NASKAHKERJASAMA AIITARA FAKULTAS SYARI'AH IAIN PURWOKERTO DENGAN FAKULTAS SYARI'AH IAIN SALATIGA No.o., 6go /In. I7/D.FS/HM. ot lxtr?ot7 Nomor : TENTANG PELAKSANAAN TRI DIIARMA Pf,RGTJRUAN TINGGI Pada hari ini, Senin tanggal delapan belas bulan Desember tahun dua ribu tujuh belas, yang bertandatangan di bawah ini: L Nama : Dr. H. Syufa'at, M.Ag NIP : 19630910 199203 1005 Jabatan : Dekan Fakultas Syari'ah IAIN Purwokerto Alamat : Jalan Jenderal Ahmad Yani Nomor 40 A Purwokerto Kode Pos 531256 Telepon 0281 435624. 028 r -628250 Faximile 0281-636553 Website www. syariah.iainpurwokerto. ac.id Email syariah@ainpurwokerto. ac. id Dalam hal ini bertindak dalam jabatannya tersebut, oleh karena itu untuk dan atas nama serta sah mewakili Fakultas Syari'ah Institut Agama lslam Negeri Purwokerto. Selanjutnya dalam Naskah Kojasama ini disebut PIIIAK PERTAMA 2. Nama : Dr. Siti Zumrohm, M.Ag. NIP : 19670115 1998032002 Jabatan : Dekan Fakultas Syariah IAIN Salatiga Alamat : Jalan Nakula Sadewa V No. 9 Kota Salatiga, Jawa Tengah Kode Pos 50722 Telepon : (0298) 341900 Faximile :(0298)323433 Website :www.syariah.iainsalatiga.ac.id Email :[email protected] Dalam hal ini bertindak dalarn jabatannya tersebut, oleh karena itu unuk dan atas nama serta sah mewakili Fakultas Syari'ah Institut Agama Islam Negeri Salatiga. -

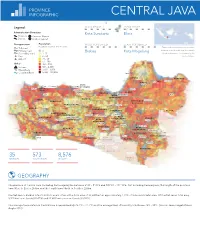

Central Java

PROVINCE INFOGRAPHIC CENTRAL JAVA Legend: MOST DENSE LEAST DENSE Administrative Boundary Kota Surakarta Blora Province Province Capital District District Capital Transportation Population MOST POPULATED LEAST POPULATED Population counts at 1km resolution Toll road The boundaries and names shown and the Primary road 0 Brebes Kota Magelang designations used on this map do not imply Secondary road 1 - 5 official endorsement or acceptance by the Port 6 - 25 United Nations. Airport 26 - 50 51 - 100 Other 101 - 500 INDRAMAYVolcanoU 501 - 2,500 Water/Lake 2,501 - 5,000 Coastline/River 5,000 - 130,000 Jepara Cirebon JEPARA REMBA NG Rembang KOTA Pati PATI KUDUS CIREBON Kudus CIREBON KOTA Tegal Pemalang PEKALON GAN Brebes KOTA Kendal Demak TEGAL Pekalongan TUB AN Semarang DEMAK KEND AL Slawi Batang Semarang Blora KUNINGAN KOTA SEMA RANG Kajen BATANG TEGAL Purwodadi PEMA LAN G GROBOGA N BOYOLALI PEKALON GAN Ungaran Ungaran Dieng Volc Complex BREB ES Slamet TEMA NGGUN G SEMA RANG BLORA BOJONEGO RO PURB ALINGGA Sundoro Salatiga KOTA BANJARN EGARA Wonosobo Temanggung KOTA BANJAR BANYUMAS Banjarnegara Sumbing Banjar TelomoyoSALATIGA SRAGEN NGAWI Purbalingga KOTA Purwokerto WONO SOBO Sragen Ngawi MA GELANG Merbabu Magelang Boyolali Surakarta MA GELANG Merapi KOTA CIAMIS KEBU MEN Mungkid Caruban SURAKARTA Karanganyar Madiun KOTA MA DIU N CILACAP Lawu Kebumen SUKO HARJO Magetan Purworejo SLEMAN Klaten MA DIU N Parigi Sukoharjo KARANGANYAR MAGETAN Cilacap KOTA Sleman PURWOREJO KLATEN NGANJUK YOGYAKARTA Yogyakarta Wonogiri Wates Yogyakarta KULON Ponorogo Bantul PROGO WONO GIRI PONOROGO BANTUL 35 573 8,576 Wonosari DISTRICTS SUB-DISTRICTS VILLAGES GUNUN G Trenggalek KIDU L PACITAN Pacitan TRENGGALEK TULUNGA GUNG GEOGRAPHY The province of Central Java (including Karimunjawa) lies between 5°40' - 8°30'S and 108°30' - 111°30'E. -

Pencegahan Mitigasi Serangan Organisme

PEMERINTAH PROVINSI JAWA TENGAH DINAS PERT ANIAN DAN PERKEBUNAN Jalan Gatot Subroto, Kompleks Tarubudayn Ungaran Telepon 024-6924 l 55 Faks1m1le 024-69210~0 Laman http://www jatengprov id 99 iii,iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii;;;;;;;iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii-.iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii-.iiiiiii;;.;;;iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii;;;;;;;;Suiiiira_t;;;;Eliiiiekiiiitriiiion-1kiiiidiiii1st-an_b_un~@:ja~te~n=gp~ro~v .:go~.id:_iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii--.;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;.;;;._.___ Nonior .;'.:J-/, 1/1 /C/Jf/1 Semarang, 3( Maret 2020 Sifat Segera Kepada Yth . Lampiran 1 (satu) lembar Kepala Dinas Pertanian Kab/Kota Perihal se-Jawa Tengah ( Tertampir) Kewaspadaan Peningkatan Seranqan OPT dan DPI Mernperhatikan surat Direktorat Jenderai Tanaman Pangan Kementerian Pertanian RI Nomor : B-1901/PW.170/C03/2020 perihal tersebut diatas, dengan mempertimbangkan keadaan cuaca pada Musim Hujan (MH) Oktober-Maret 2019/2020 yang kondusif bagi perkembangan Organime Pengganggu Tumbuhan (OPT) dan kejadian dampak perubahan iklim (DPI) Janjir diperlukan upaya-upaya dan langkah operasional untuk mengantisipasi meluasnya serangan OPT dan DPI tersebut. Saat ini luas serangan OPT, khususnyn tikus dan wereng batang coklat (WBC) cenderung meningkat di beberapa wilayah sentra produl<si dan berpotensi menurunkan produksi tanaman pangan Sehubungan dengan hal tersebut, kami mohon Saudara untuk mengantisipas.i meluasnya kejadian serangan OPT dan DPI dengan melaksanakan langkah-langkah sebagai berikut : 1. Mengintensifkan identifikasi potensi dan pendataan serangan OPT serta kejadian DPI, khususnya banjir. Data tersebut dilaporkan secara berkala . 2. Meningkatkan sosialisasi potensi serangan OPT dan kejadian DPI di tingkat kelompok tani serta melaksanakan gerakan pengendalian apabila diperlukan. 3. Mendorong petani ikut asuransi pertanian untuk menjamin usaha taninya 4. Menyiapkan bahan dan sarana yang diperlukan untuk mengantisipas, kejadian tak terduga berupa stok pestisida, bantuan benih dan lair.-lain.