Hong Kong Landscapes Shaping the Barren Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geodiversity, Geoconservation and Geotourism in Hong Kong Global

Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 126 (2015) 426–437 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pgeola Geodiversity, geoconservation and geotourism in Hong Kong Global Geopark of China Lulin Wang *, Mingzhong Tian, Lei Wang School of Earth Science and Resources, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, China A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: In addition to being an international financial center, Hong Kong has rich geodiversity, in terms of a Received 22 November 2014 representative and comprehensive system of coastal landscapes, with scientific value in the study of Received in revised form 20 February 2015 Quaternary global sea-level changes, and esthetic, recreational and cultural value for tourism. The value Accepted 26 February 2015 of the coastal landscapes in Hong Kong was globally recognized when Hong Kong Global Geopark Available online 14 April 2015 (HKGG), which was developed under the well-established framework of Hong Kong Country Parks and Marine Parks, was accepted in the Global Geoparks Network (GGN) in 2011. With over 30 years of Keywords: experience gained from managing protected areas and a concerted effort to develop geoconservation and Coastal landscape geotourism, HKGG has reached a mature stage of development and can provide a well-developed Hong Kong Global Geopark Geodiversity example of successful geoconservation and geotourism in China. This paper analyzes the geodiversity, Geoconservation geoconservation and geotourism of HKGG. The main accomplishments summarized in this paper are Geotourism efficient conservation management, an optimized tourism infrastructure, a strong scientific interpretation system, mass promotion and education materials, active exchange with other geoparks, continuous training, and effective collaboration with local communities. -

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5482 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5483 Yau Tsim Mong Block 2, The Long Beach 5484 Kwun Tong Dorsett Kwun Tong, Hong Kong 5486 Wan Chai Victoria Heights, 43A Stubbs Road 5487 Islands Tower 3, The Visionary 5488 Sha Tin Yue Chak House, Yue Tin Court 5492 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5496 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5497 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5498 Kowloon City Sik Man House, Ho Man Tin Estate 5499 Wan Chai 168 Tung Lo Wan Road 5500 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5501 Sai Kung Clear Water Bay Apartments 5502 Southern Red Hill Park 5503 Sai Kung Po Lam Estate, Po Tai House 5504 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5505 Islands Ying Yat House, Yat Tung Estate 5506 Kwun Tong Block 17, Laguna City 5507 Crowne Plaza Hong Kong Kowloon East Sai Kung 5509 Hotel Eastern Tower 2, Pacific Palisades 5510 Kowloon City Billion Court 5511 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5512 Central & Western Tai Fat Building 5513 Wan Chai Malibu Garden 5514 Sai Kung Alto Residences 5515 Wan Chai Chee On Building 5516 Sai Kung Block 2, Hillview Court 5517 Tsuen Wan Hoi Pa San Tsuen 5518 Central & Western Flourish Court 5520 1 Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Wong Tai Sin Fu Tung House, Tung Tau Estate 5521 Yau Tsim Mong Tai Chuen Building, Cosmopolitan Estates 5523 Yau Tsim Mong Yan Hong Building 5524 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5525 Sha Tin Yiu Ping House, Yiu On Estate 5526 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5529 Wan Chai Block E, Beverly Hill 5530 Yau Tsim Mong Tower 1, The Harbourside 5531 Yuen Long Wah Choi House, Tin Wah Estate 5532 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5533 Yau Tsim Mong Paradise Square 5534 Kowloon City Tower 3, K. -

Ping Shan K a Works in Progress a G W D

n g d . P D O R D n OA i R T E TA R A D D G A U N O A A R Q O Y W G U S N R e Tai Kiu E New Village A 0 W N 1 N U Tai Wai B < H I L A I O s Sheung M T Y DO NOT SCALE DRAWING. CHECK ALL DIMENSIONS ON SITE. K N YUEN LONG KAU HUI Tsuen G SHUI PIN WAI A Cheung I Nam Pin Wai N h O P p INTERCHANGE Chun Hing A N U A a U P STREE T T Ying Lung Wai l Works in progress L G H p ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. San Tsuen I l E O C N K N u E N G2 Wai O L R u D LON G N O l G YA E l T RO A g A a AD Legend W I n U H A a D h c OVE ARUP & PARTNERS HONG KONG LIMITED. PI O N I C T H g d G h M i n R i HA ROAD la a d l A T il u S G u N U B N n 0 A T I G1 2 M A N J p R P I H U YUEN LONG O E N NING ROAD C B Yuen Long Station a E F T L C R E O H G O E N A T D E D N G L A R A Y 2 Pak Fa Tsuen O Development Area T I 0 P W S P R S D Shui Pin Wai Estate S S A I T I A Hang Tau I G R K O p N FOOK TA K ST T E U N Works in progress O R E Sha Chaus Lei Tsuen G A T U L Pok Oi I I l E E S S G S Y L S T H D H N Sun Yuen Long Centre H ON SHUN S T p e Hang Mei T K E U A U U I T S A O T U A S Pok Oi I K Tsuen R H N N N n T SAU FU ST G Hospital C EE RE Hospital E U TR T N YUEN LONG G S Land Use Zoning T P I W FA N SHUI CHE K KIU N T E I A n U A R H K N Y Fiori U O S M Ping Shan K A Works in progress a G W D P N LONG LOK RO A AD U A h I Y K CASTLE PEAK ROAD - YUEN LONG Shui Pin LIGHT RAIL Road rk R C a R P Wai CASTLE P D EAK e D R by th OAD - YUEN LONG D ila K Ping V A POK OI IU g H WONG Hon O S T INTERCHANGE TREET ila Shui Pin R V A r N P Tsuen I Shui Pin Tsuen ONG D P N H IN K e G Yuen -

Branch List English

Telephone Name of Branch Address Fax No. No. Central District Branch 2A Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2160 8888 2545 0950 Des Voeux Road West Branch 111-119 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 2546 1134 2549 5068 Shek Tong Tsui Branch 534 Queen's Road West, Shek Tong Tsui, Hong Kong 2819 7277 2855 0240 Happy Valley Branch 11 King Kwong Street, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 2838 6668 2573 3662 Connaught Road Central Branch 13-14 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2841 0410 2525 8756 409 Hennessy Road Branch 409-415 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2835 6118 2591 6168 Sheung Wan Branch 252 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2541 1601 2545 4896 Wan Chai (China Overseas Building) Branch 139 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2529 0866 2866 1550 Johnston Road Branch 152-158 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2574 8257 2838 4039 Gilman Street Branch 136 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2135 1123 2544 8013 Wyndham Street Branch 1-3 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong 2843 2888 2521 1339 Queen’s Road Central Branch 81-83 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong 2588 1288 2598 1081 First Street Branch 55A First Street, Sai Ying Pun, Hong Kong 2517 3399 2517 3366 United Centre Branch Shop 1021, United Centre, 95 Queensway, Hong Kong 2861 1889 2861 0828 Shun Tak Centre Branch Shop 225, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2291 6081 2291 6306 Causeway Bay Branch 18 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2572 4273 2573 1233 Bank of China Tower Branch 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong 2826 6888 2804 6370 Harbour Road Branch Shop 4, G/F, Causeway Centre, -

Cameron Dueck Explored Beyond the Beaten Track

a tale of two cities CAMERON DUECK EXPLORED BEYOND THE BEATEN TRACK AROUND THE WATERS OF HIS HOMETOWN, HONG KONG Baona/Getty The old and the new: a traditional junk crosses the glassy waters of Hong Kong Harbour 52 53 ‘Hong Kong is so much more than just a glittering metropolis’ We had just dropped the anchor in a small bay, and I was standing on the deck of our Hallberg-Rassy, surveying the turquoise water and shore that rose steep and green around us. At one end of the bay stood a ramshackle cluster of old British military buildings and an abandoned pearl farm, now covered in vines that were reclaiming the land, while through the mouth of the bay I could see a few high- prowed fishing boats working the South China Sea. I felt drunk with the thrill of new discovery, even though we were in our home waters. I was surprised that I’d never seen this gem of a spot before, and it made me wonder what else I’d find. Hong Kong has been my home for nearly 15 years, during which I’ve hiked from its lush valleys to the tops of its mountain peaks and paddled miles of its rocky shoreline in a sea kayak. I pride myself in having seen Lui/EyeEm/Getty Siu Kwan many of the far-flung corners of this territory. The little-known beauty of Hong Kong’s Sai Kung district I’ve also been an active weekend sailor, crewing on racing yachts and sailing out of every local club. -

1 Appendix 1 Issue of “2014 Hong Kong Definitive Stamps” and New

Appendix 1 Issue of “2014 Hong Kong Definitive Stamps” and New Philatelic Products on 24 July 2014 A set of new “2014 Hong Kong Definitive Stamps” is designed by Ms. Shirman LAI and printed in lithography by Joh. Enschede B.V. of the Netherlands. “2014 Hong Kong Definitive Stamps” will be released on 24 July 2014. In parallel, “2006 Hong Kong Definitive Stamps” on the theme of birds, officially released on 31 December 2006, will continue to be on sale while stock lasts. In addition to the stamps and philatelic products of the new set of definitive stamps, an official souvenir cover and other philatelic products have been created to commemorate the concurrent sale of two sets of Hong Kong definitive stamps. They will also be released on the stamp issue day. Official First Day Covers for “2014 Hong Kong Definitive Stamps” at $1.2 each for small-sized covers and $2.2 each for large-sized covers as well as Official Souvenir Covers to commemorate the concurrent sale of the 2006 Hong Kong Definitive Stamps and the 2014 Hong Kong Definitive Stamps at $1.2 each will be on sale at all post offices from 10 July 2014. Advance orders for the additional philatelic products comprising two sets of definitive stamps can be placed at all post offices and online or mailed in from 26 May to 15 June 2014. These items and associated philatelic products will be displayed at the General Post Office, Tsim Sha Tsui Post Office, Tsuen Wan Post Office, Sha Tin Central Post Office and Tuen Mun Central Post Office from July 10. -

List of Recognized Villages Under the New Territories Small House Policy

LIST OF RECOGNIZED VILLAGES UNDER THE NEW TERRITORIES SMALL HOUSE POLICY Islands North Sai Kung Sha Tin Tuen Mun Tai Po Tsuen Wan Kwai Tsing Yuen Long Village Improvement Section Lands Department September 2009 Edition 1 RECOGNIZED VILLAGES IN ISLANDS DISTRICT Village Name District 1 KO LONG LAMMA NORTH 2 LO TIK WAN LAMMA NORTH 3 PAK KOK KAU TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 4 PAK KOK SAN TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 5 SHA PO LAMMA NORTH 6 TAI PENG LAMMA NORTH 7 TAI WAN KAU TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 8 TAI WAN SAN TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 9 TAI YUEN LAMMA NORTH 10 WANG LONG LAMMA NORTH 11 YUNG SHUE LONG LAMMA NORTH 12 YUNG SHUE WAN LAMMA NORTH 13 LO SO SHING LAMMA SOUTH 14 LUK CHAU LAMMA SOUTH 15 MO TAT LAMMA SOUTH 16 MO TAT WAN LAMMA SOUTH 17 PO TOI LAMMA SOUTH 18 SOK KWU WAN LAMMA SOUTH 19 TUNG O LAMMA SOUTH 20 YUNG SHUE HA LAMMA SOUTH 21 CHUNG HAU MUI WO 2 22 LUK TEI TONG MUI WO 23 MAN KOK TSUI MUI WO 24 MANG TONG MUI WO 25 MUI WO KAU TSUEN MUI WO 26 NGAU KWU LONG MUI WO 27 PAK MONG MUI WO 28 PAK NGAN HEUNG MUI WO 29 TAI HO MUI WO 30 TAI TEI TONG MUI WO 31 TUNG WAN TAU MUI WO 32 WONG FUNG TIN MUI WO 33 CHEUNG SHA LOWER VILLAGE SOUTH LANTAU 34 CHEUNG SHA UPPER VILLAGE SOUTH LANTAU 35 HAM TIN SOUTH LANTAU 36 LO UK SOUTH LANTAU 37 MONG TUNG WAN SOUTH LANTAU 38 PUI O KAU TSUEN (LO WAI) SOUTH LANTAU 39 PUI O SAN TSUEN (SAN WAI) SOUTH LANTAU 40 SHAN SHEK WAN SOUTH LANTAU 41 SHAP LONG SOUTH LANTAU 42 SHUI HAU SOUTH LANTAU 43 SIU A CHAU SOUTH LANTAU 44 TAI A CHAU SOUTH LANTAU 3 45 TAI LONG SOUTH LANTAU 46 TONG FUK SOUTH LANTAU 47 FAN LAU TAI O 48 KEUNG SHAN, LOWER TAI O 49 KEUNG SHAN, -

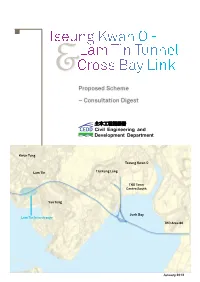

Tseung Kwan O - 及 Lam Tin Tunnel Cross Bay Link

Tseung Kwan O - 及 Lam Tin Tunnel Cross Bay Link Proposed Scheme – Consultation Digest Kwun Tong Tseung Kwan O Lam Tin Tiu Keng Leng TKO Town Centre South Yau Tong Junk Bay Lam Tin Interchange TKO Area 86 January 2012 Project Information Legends: Benefits Proposed Interchange • Upon completion of Route 6, the new road • The existing Tseung Kwan O Tunnel is operating Kai Tak Tseung Kwan O - Lam Tin Tunnel network will relieve the existing heavily near its maximum capacity at peak hours. The trafficked road network in the central and TKO-LT Tunnel and CBL will relieve the existing Kowloon Bay Cross Bay Link eastern Kowloon areas, and hence reduce travel traffic congestion and cater for the anticipated Kwun Tong Trunk Road T2 time for vehicles across these areas and related traffic generated from the planned development Yau Ma Tei Central Kowloon Route environmental impacts. of Tseung Kwan O. To Kwa Wan Lam Tin Tseung Kwan O Table 1: Traffic Improvement - Kwun Tong District Yau Tong From Yau Tong to Journey Time West Kowloon Area (Peak Hour) Current (2012) 22 min. Schematic Alignment of Route 6 and Cross Bay Link Via Route 6 8 min. Traffic Congestion at TKO Tunnel The Tseung Kwan O - Lam Tin Tunnel (TKO-LT Tunnel) At present, the existing Tseung Kwan O Tunnel is towards Kowloon in the morning is a dual-two lane highway of approximately 4.2km the main connection between Tseung Kwan O and Table 2: Traffic Improvement - Tseung Kwan O long, connecting Tseung Kwan O (TKO) and East urban areas of Kowloon. -

GEO REPORT No. 282

EXPERT REPORT ON THE GEOLOGY OF THE PROPOSED GEOPARK IN HONG KONG GEO REPORT No. 282 R.J. Sewell & D.L.K. Tang GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING OFFICE CIVIL ENGINEERING AND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT THE GOVERNMENT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION EXPERT REPORT ON THE GEOLOGY OF THE PROPOSED GEOPARK IN HONG KONG GEO REPORT No. 282 R.J. Sewell & D.L.K. Tang This report was originally produced in June 2009 as GEO Geological Report No. GR 2/2009 2 © The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region First published, July 2013 Prepared by: Geotechnical Engineering Office, Civil Engineering and Development Department, Civil Engineering and Development Building, 101 Princess Margaret Road, Homantin, Kowloon, Hong Kong. - 3 - PREFACE In keeping with our policy of releasing information which may be of general interest to the geotechnical profession and the public, we make available selected internal reports in a series of publications termed the GEO Report series. The GEO Reports can be downloaded from the website of the Civil Engineering and Development Department (http://www.cedd.gov.hk) on the Internet. Printed copies are also available for some GEO Reports. For printed copies, a charge is made to cover the cost of printing. The Geotechnical Engineering Office also produces documents specifically for publication in print. These include guidance documents and results of comprehensive reviews. They can also be downloaded from the above website. The publications and the printed GEO Reports may be obtained from the Government’s Information Services Department. Information on how to purchase these documents is given on the second last page of this report. -

Marine Water Quality in Hong Kong in 2004 P 2.2 Mirs Bay Wcz Port Shelter Wcz Eastern Waters 2 Tolo Harbour & Channel Wcz

MIRS BAY WCZ PORT SHELTER WCZ EASTERN WATERS 2 TOLO HARBOUR & CHANNEL WCZ Chapter 2 – Eastern Waters Water Quality in 2004 2.1 The eastern waters cover an area of 900 km2. They include three Water Control Zones (WCZs) i.e. the Mirs Bay, Port Shelter and Tolo Harbour & Channel WCZs. Mirs Bay is the eastern most water of Hong Kong and is under considerable oceanic influence. While Port Shelter opens to the southern part of Mirs Bay, Tolo Harbour is connected to northern part through a narrow channel. Port Shelter, Tolo Harbour and Crooked Harbour in Mirs Bay are gazetted secondary recreational waters. The general water quality of the eastern waters is good, supporting a variety of marine life including corals. There are three marine parks and 21 fish culture zones in the eastern waters (Figure 1.6). Mirs Bay Water Control Zone 2.2 Mirs Bay has good and stable water quality, with high dissolved oxygen (DO), low turbidity, nutrients and sewage bacteria. Starling Inlet in the northern part bordering Shenzhen is subject to localized effects of Sha Tau Kok town and has slightly higher pollutant levels. In 2004, Mirs Bay has experienced an increase of DO by 16% on average, in particular at the northern stations, e.g. MM1- MM7, also at MM13, MM19 (Table 2.4). The mean annual ammonia nitrogen (NH4-N) concentration in the bay was found to have increased by 57% (similar to some other waters). However, there was no marked increase in total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN) or total inorganic nitrogen (TIN), and the chlorophyll-a level remained relatively stable indicating that there was no marked increase in phytoplankton biomass in the bay. -

D1 Shui Chuen O

D 1 North km 5 East D1 9.5 hours & Ctrl. Shui Chuen O - Monkey Hill N.T. BRIEF ( ) Take the path between Girl Guides Association Pok Hong Campsite and Shui Chuen O Estate, Sha Tin to Sha Tin Pass. Continue along Unicorn Ridge and the path on the north side of the Lion Rock. Proceed to Kowloon Pass and Beacon Hill before arriving at Tai Po Road via the Eagle's Nest Nature Trail. When walking along the section from Sha Tin Pass to Beacon Hill (i.e. Section 5 of the MacLehose Trail), you may visit the wartime relics and learn about the history of the war period from the interpretative sign. S (KK112767) - 10 STARTING POINT Shui Chuen O Estate, Sha Tin - Walk along Shui Chuen Au Street from MTR Sha Tin Wai Station for Hiking Route about 10 minutes. Wilson Trail MacLehose Trail Footpath F (KK068743) Vehicular Access Road - 81 Distance Post FINISHING Toilet POINT “Monkey Hill”, Tai Po Road - Take Kowloon Motor Bus Route No. 81 to MTR Prince Edward Direction of Movement Station. Kowloon East Cross-section Uphill Path S F 72 Lion Pavilion Beacon Hill 73 D 1 North km 5 East D1 9.5 hours & Ctrl. Shui Chuen O - Monkey Hill N.T. BRIEF ( ) Take the path between Girl Guides Association Pok Hong Campsite and Shui Chuen O Estate, Sha Tin to Sha Tin Pass. Continue along Unicorn Ridge and the path on the north side of the Lion Rock. Proceed to Kowloon Pass and Beacon Hill before arriving at Tai Po Road via the Eagle's Nest Nature Trail. -

Office Address of the Labour Relations Division

If you wish to make enquiries or complaints or lodge claims on matters related to the Employment Ordinance, the Minimum Wage Ordinance or contracts of employment with the Labour Department, please approach, according to your place of work, the nearby branch office of the Labour Relations Division for assistance. Office address Areas covered Labour Relations Division (Hong Kong East) (Eastern side of Arsenal Street), HK Arts Centre, Wan Chai, Causeway Bay, 12/F, 14 Taikoo Wan Road, Taikoo Shing, Happy Valley, Tin Hau, Fortress Hill, North Point, Taikoo Place, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong. Shau Ki Wan, Chai Wan, Tai Tam, Stanley, Repulse Bay, Chung Hum Kok, South Bay, Deep Water Bay (east), Shek O and Po Toi Island. Labour Relations Division (Hong Kong West) (Western side of Arsenal Street including Police Headquarters), HK Academy 3/F, Western Magistracy Building, of Performing Arts, Fenwick Pier, Admiralty, Central District, Sheung Wan, 2A Pok Fu Lam Road, The Peak, Sai Ying Pun, Kennedy Town, Cyberport, Residence Bel-air, Hong Kong. Aberdeen, Wong Chuk Hang, Deep Water Bay (west), Peng Chau, Cheung Chau, Lamma Island, Shek Kwu Chau, Hei Ling Chau, Siu A Chau, Tai A Chau, Tung Lung Chau, Discovery Bay and Mui Wo of Lantau Island. Labour Relations Division (Kowloon East) To Kwa Wan, Ma Tau Wai, Hung Hom, Ho Man Tin, Kowloon City, UGF, Trade and Industry Tower, Kowloon Tong (eastern side of Waterloo Road), Wang Tau Hom, San Po 3 Concorde Road, Kowloon. Kong, Wong Tai Sin, Tsz Wan Shan, Diamond Hill, Choi Hung Estate, Ngau Chi Wan and Kowloon Bay (including Telford Gardens and Richland Gardens).