Southern New Mexico Historical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NMSU Athletics Master Plan 2018

NEW MEXICO STATE UNIVERSITY ATHLETICS MASTER PLAN NEW MEXICO STATE UNIVERSITY | ATHLETICS FACILITIES MASTER PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Directory 3 Participants 4 SECTION 1 / OVERVIEW Executive Summary 7 SECTION 2 / ATHLETIC VENUE AND DEPARTMENTS RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 Athletic Support Venues 17 Coca-Cola® Weight Training Facility Fulton Athletic Center Hall of Legends & Aggie Letterman Ring of Honor 2.2 Baseball 25 Presley Askew Baseball Field 2.3 Basketball - Men’s & Women’s 29 Pan American Center Pan Am Annex 2.4 Football 47 Memorial Stadium and Locker Room Field House Football Team Building Football Coaches Office 2.5 Multi-Use 60 Practice Pavilion 2.6 Golf Men’s & Women’s 62 NMSU Golf Course and Clubhouse 2.7 Soccer 63 NMSU Soccer Complex 2.8 Softball 65 NMSU Softball Complex 1 NEW MEXICO STATE UNIVERSITY | ATHLETICS FACILITIES MASTER PLAN SECTION 2 / ATHLETIC VENUE AND DEPARTMENTS RECOMMENDATIONS (BUDGETARY COSTS INCLUDED) 2.9 Swimming & Diving 67 Natatorium 2.10 Tennis - Men’s & Women’s 68 Tennis Complex 2.11 Track & Field 70 NMSU Track & Field Complex 2.12 Volleyball 72 Pan American Center Pan Am Annex 2.13 Departments and Services 73 Administration Athletic Training Business & Finance Cheer Squad Compliance & Eligibility Development Equipment Marketing & Promotions NM State Sports Properties Strength & Conditioning Student Development / Academic Support Ticket Office SECTION 3 / APPENDIX Appendix 81 ADA Analysis Memorial Stadium Entry Renderings 2 NEW MEXICO STATE UNIVERSITY | ATHLETICS FACILITIES MASTER PLAN DIRECTORY PREPARED FOR: -

Steering Committee

Steering Committee Year-End Report - 2013 Steven Aftergood Federation of American Scientists For the OpenTheGovernment.org coalition (OTG), 2013 was a period of Gary Bass Bauman Foundation accelerated growth in our leadership role in charting a path to greater Tom Blanton openness and an improved Freedom of Information Act, and working to National Security Archive leverage the US’s participation in the Open Government Partnership to push Rick Blum for meaningful openness reforms. Sunshine in Government Initiative As described below, our notable successes over the last year include: Lynne Bradley American Library -We coordinated and published an internationally-praised evaluation of the Association US government implementation of the first open government National Action Danielle Brian* Project On Government Plan and created a model National Action Plan to set the bar even higher for Oversight the second plan. Kevin Goldberg American Society of News Editors -OTG staff coordinated community efforts to improve the Freedom of Conrad Martin Information Act and successfully combatted attempts to roll back the right to Fund for Constitutional Government know in the Farm Bill. (Ex-officio member) Katherine McFate/ -Amplified transparency issues in the wake of revelations about the National Sean Moulton OMB Watch Security Agency’s mass surveillance programs. Michael Ostrolenk Liberty Coalition The Difference OTG Makes Thomas Susman National Freedom of Delivering Results in the Open Government Partnership Information Coalition David Sobel OpenTheGovernment.org set a high bar for civil society engagement in the Electronic Frontier Foundation National Action Plans created through the Open Government Partnership. Anne Weismann To create an unprecedented evaluation of the government’s Citizens for Responsibility & Ethics implementation of the plan, OTG worked with more than thirty civil in Washington John Wonderlich society organizations and academic institutions to develop and apply Sunlight Foundation evaluation metrics to the government’s performance. -

SUPPLEMENT NO. 6 DI Administration Cabinet 2/10

SUPPLEMENT NO. 6 DI Administration Cabinet 2/10 COMMITTEE APPOINTMENTS This supplement contains the current committee composition chart with a description of the vacancy, committee history, nominee list and nomination forms for the following committees: 1. Committee on Competitive Safeguards and Medical Aspects of Sports. 2. Minority Opportunities and Interests Committee. 3. Olympic Sports Liaison Committee. 4. Postgraduate Scholarship Committee. 5. Research Committee. 6. Committee on Sportsmanship and Ethical Conduct. 7. Walter Byers Scholarship Committee. 8. Committee on Women’s Athletics. 9. Division I Amateurism Fact-Finding Committee. (One reappointment and two vacancies.) 10. Division I Committee on Athletics Certification. 11. Division I Men’s Basketball Issues Committee. 12. Division I Women’s Basketball Issues Committee. 13. Division I Football Issues Committee. (Three reappointments.) 14. Division I Committee on Infractions. 15. Division I Legislative Review/Interpretations Committee. 16. Division I Progress Toward Degree Waiver Committee. 17. Division I Student-Athlete Reinstatement Committee. 18. Division I Baseball Committee. 19. Division I Men’s Basketball Committee. 20. Division I Women’s Basketball Committee. 21. Women’s Bowling Committee. 22. Men’s and Women’s Fencing Committee. (No nominees.) 23. Division I Field Hockey Committee. 24. Division I Football Championship Committee. (One reappointment and three vacancies.) 25. Division I Men’s Golf Committee. 26. Division I Women’s Golf Committee. 27. Men’s Gymnastics Committee. (No nominees.) 28. Women’s Gymnastics Committee. 29. Division I Men’s Ice Hockey Committee. 30. Women’s Ice Hockey Committee. 31. Division I Men’s Lacrosse Committee. 32. Division I Women’s Lacrosse Committee. 33. Men’s and Women’s Rifle Committee. -

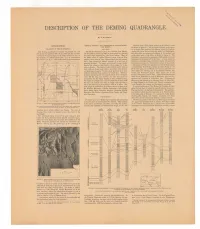

Description of the Deming Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE DEMING QUADRANGLE, By N. H. Darton. INTRODUCTION. GENERAL GEOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY OF SOUTHWESTERN Paleozoic rocks. The general relations of the Paleozoic rocks NEW MEXICO. are shown in figure 3. 2 All the earlier Paleozoic rocks appear RELATIONS OF THE QUADRANGLE. STRUCTURE. to be absent from northern New Mexico, where the Pennsyl- The Deming quadrangle is bounded by parallels 32° and The Rocky Mountains extend into northern New Mexico, vanian beds lie on the pre-Cambrian rocks, but Mississippian 32° 30' and by meridians 107° 30' and 108° and thus includes but the southern part of the State is characterized by detached and older rocks are extensively developed in the southern and one-fourth of a square degree of the earth's surface, an area, in mountain ridges separated by wide desert bolsons. Many of southwestern parts of the State, as shown in figure 3. The that latitude, of 1,008.69 square miles. It is in southwestern the ridges consist of uplifted Paleozoic strata lying on older Cambrian is represented by sandstone, which appears to extend New Mexico (see fig. 1), a few miles north of the international granites, but in some of them Mesozoic strata also are exposed, throughout the southern half of the State. At some places the and a large amount of volcanic material of several ages is sandstone has yielded Upper Cambrian fossils, and glauconite 109° 108° 107" generally included. The strata are deformed to some extent. in disseminated grains is a characteristic feature in many beds. Some of the ridges are fault blocks; others appear to be due Limestones of Ordovician age outcrop in all the larger ranges solely to flexure. -

Gannett Acquires 11 Media Organizations from Digital First Media

Gannett acquires 11 media organizations from Digital First Media June 1, 2015 MCLEAN, Va.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Jun. 1, 2015-- Gannett Co., Inc. today announced that it has completed the acquisition of the remaining 59.36% interest in the Texas-New Mexico Newspapers Partnership that it did not own from Digital First Media. The deal was completed through the assignment of Gannett’s 19.49% interest in the California Newspapers Partnership and additional cash consideration. As a result, Gannett will own 100% of the Texas-New Mexico Newspapers Partnership and will no longer have any ownership interest in California Newspapers Partnership. The news organizations acquired and the three states in which they reside include: Texas -- El Paso Times; New Mexico -- Alamogordo Daily News; Carlsbad Current-Argus; The Daily Times in Farmington; Deming Headlight; Las Cruces Sun-News; Silver City Sun-News; Pennsylvania -- Chambersburg Public Opinion; Hanover Evening Sun; Lebanon Daily News; and the York Daily Record. “We are very pleased to welcome these well-respected media organizations to U.S. Community Publishing as we further our efforts to expand our reach as the best local media company in America for consumers and businesses,” said Robert Dickey, president of U.S. Community Publishing and CEO-designate of Gannett “SpinCo” following the separation of the company mid-2015. “There is no media company in America that knows local communities better and with USA TODAY, the company has outstanding national to local scale.” With this acquisition, the publishing segment of Gannett provides hundreds of outstanding affiliated digital, mobile and print products in 92 local markets throughout 33 states plus Guam, and in 16 markets in the U.K. -

Cultural Resources Overview Desert Peaks Complex of the Organ Mountains – Desert Peaks National Monument Doña Ana County, New Mexico

Cultural Resources Overview Desert Peaks Complex of the Organ Mountains – Desert Peaks National Monument Doña Ana County, New Mexico Myles R. Miller, Lawrence L. Loendorf, Tim Graves, Mark Sechrist, Mark Willis, and Margaret Berrier Report submitted to the Wilderness Society Sacred Sites Research, Inc. July 18, 2017 Public Version This version of the Cultural Resources overview is intended for public distribution. Sensitive information on site locations, including maps and geographic coordinates, has been removed in accordance with State and Federal antiquities regulations. Executive Summary Since the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) in 1966, at least 50 cultural resource surveys or reviews have been conducted within the boundaries of the Desert Peaks Complex. These surveys were conducted under Sections 106 and 110 of the NHPA. More recently, local avocational archaeologists and supporters of the Organ Monument-Desert Peaks National Monument have recorded several significant rock art sites along Broad and Valles canyons. A review of site records on file at the New Mexico Historic Preservation Division and consultations with regional archaeologists compiled information on over 160 prehistoric and historic archaeological sites in the Desert Peaks Complex. Hundreds of additional sites have yet to be discovered and recorded throughout the complex. The known sites represent over 13,000 years of prehistory and history, from the first New World hunters who gazed at the nighttime stars to modern astronomers who studied the same stars while peering through telescopes on Magdalena Peak. Prehistoric sites in the complex include ancient hunting and gathering sites, earth oven pits where agave and yucca were baked for food and fermented mescal, pithouse and pueblo villages occupied by early farmers of the Southwest, quarry sites where materials for stone tools were obtained, and caves and shrines used for rituals and ceremonies. -

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Prepared in cooperation with New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources 1997 MINERAL AND ENERGY RESOURCES OF THE MIMBRES RESOURCE AREA IN SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Cover: View looking south to the east side of the northeastern Organ Mountains near Augustin Pass, White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico. Town of White Sands in distance. (Photo by Susan Bartsch-Winkler, 1995.) MINERAL AND ENERGY RESOURCES OF THE MIMBRES RESOURCE AREA IN SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO By SUSAN BARTSCH-WINKLER, Editor ____________________________________________________ U. S GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OPEN-FILE REPORT 97-521 U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Socorro U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mark Shaefer, Interim Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Service Center Box 25286, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government MINERAL AND ENERGY RESOURCES OF THE MIMBRES RESOURCE AREA IN SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO Susan Bartsch-Winkler, Editor Summary Mimbres Resource Area is within the Basin and Range physiographic province of southwestern New Mexico that includes generally north- to northwest-trending mountain ranges composed of uplifted, faulted, and intruded strata ranging in age from Precambrian to Recent. -

Inventory of American Sheet Music (1844-1949)

University of Dubuque / Charles C. Myers Library INVENTORY OF AMERICAN SHEET MUSIC (1844 – 1949) May 17, 2004 Introduction The Charles C. Myers Library at the University of Dubuque has a collection of 573 pieces of American sheet music (of which 17 are incomplete) housed in Special Collections and stored in acid free folders and boxes. The collection is organized in three categories: African American Music, Military Songs, and Popular Songs. There is also a bound volume of sheet music and a set of The Etude Music Magazine (32 items from 1932-1945). The African American music, consisting of 28 pieces, includes a number of selections from black minstrel shows such as “Richards and Pringle’s Famous Georgia Minstrels Songster and Musical Album” and “Lovin’ Sam (The Sheik of Alabami)”. There are also pieces of Dixieland and plantation music including “The Cotton Field Dance” and “Massa’s in the Cold Ground”. There are a few pieces of Jazz music and one Negro lullaby. The group of Military Songs contains 148 pieces of music, particularly songs from World War I and World War II. Different branches of the military are represented with such pieces as “The Army Air Corps”, “Bell Bottom Trousers”, and “G. I. Jive”. A few of the delightful titles in the Military Songs group include, “Belgium Dry Your Tears”, “Don’t Forget the Salvation Army (My Doughnut Girl)”, “General Pershing Will Cross the Rhine (Just Like Washington Crossed the Delaware)”, and “Hello Central! Give Me No Man’s Land”. There are also well known titles including “I’ll Be Home For Christmas (If Only In my Dreams)”. -

Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett

Library of Congress Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett Redfield Georgia B. FEB 15 1937 [?] 2/11/37 512 words Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett Given In An Interview. Feb. 9-1937 “As an ‘old-timer’-as you say-I will be glad to tell you anything you would like to hear of my life in our Sunshine State-New Mexico”; said Elizabeth Garrett in an appreciated interview graciously granted this writer. Appreciated because undue publicity of her splendid achievuments and of her private life, is avoided by this famous but unspoiled musician and composer. “My father, Pat Garrett came to Fort Sumner New Mexico in 1878. He and my mother, who was Polinari Gutierez Gutiernez , were married in Fort Sumner. “I”Was born at Eagle Creek, up above the Ruidoso in the White Mountain country. “We moved to Roswell (five miles east) while I was yet an infant. I have never been back to my birthplace but believe a lodge has been built on our old mountain home site. “You ask what I think of the Elizabeth Garrett bill presented at this session of the legislature? To grant me a monthly payment during my lifetime for what I have accomplished of the State Song, I think was a beautiful tho'ught. Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett http://www.loc.gov/resource/wpalh1.19181508 Library of Congress “I owe appreciation and thanks to New Mexico people and particulary to Grace T. Bear and to the “Club o' Ten” as the originators of the idea. If this bill is passed New Mexico will be the first state that has given such evidence of appreciation (in such a distinctive way) to a composer & autho'r of a State Song. -

Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1t1nf085 No online items Inventory of the Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Sara Gunasekara & Jared Campbell Department of Special Collections General Library University of California, Davis Davis, CA 95616-5292 Phone: (530) 752-1621 Fax: (530) 754-5758 Email: [email protected] © 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Christopher A. D-435 1 Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Collector: Reynolds, Christopher A. Title: Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Date (inclusive): circa 1800-1985 Extent: 15.3 linear feet Abstract: Christopher A. Reynolds, Professor of Music at the University of California, Davis, has identified and collected sheet music written by women composers active in North America and England. This collection contains over 3000 songs and song publications mostly published between 1850 and 1950. The collection is primarily made up of songs, but there are also many works for solo piano as well as anthems and part songs. In addition there are books written by the women song composers, a letter written by Virginia Gabriel in the 1860s, and four letters by Mrs. H.H.A. Beach to James Francis Cooke from the 1920s. Physical location: Researchers should contact Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Repository: University of California, Davis. General Library. Dept. of Special Collections. Davis, California 95616-5292 Collection number: D-435 Language of Material: Collection materials in English Biography Christoper A. Reynolds received his PhD from Princeton University. He is Professor of Music at the University of Californa, Davis and author of Papal Patronage and the Music of St. -

Intraparty in the US Congress.Pages

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2cd17764 Author Bloch Rubin, Ruth Frances Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ! ! ! ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! by! Ruth Frances !Bloch Rubin ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley ! Committee in charge: Professor Eric Schickler, Chair Professor Paul Pierson Professor Robert Van Houweling Professor Sean Farhang ! ! Fall 2014 ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! Copyright 2014 by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Eric Schickler, Chair The purpose of this dissertation is to supply a simple and synthetic theory to help us to understand the development and value of organized intraparty blocs. I will argue that lawmakers rely on these intraparty organizations to resolve several serious collective action and coordination problems that otherwise make it difficult for rank-and-file party members to successfully challenge their congressional leaders for control of policy outcomes. In the empirical chapters of this dissertation, I will show that intraparty organizations empower dissident lawmakers to resolve their collective action and coordination challenges by providing selective incentives to cooperative members, transforming public good policies into excludable accomplishments, and instituting rules and procedures to promote group decision-making. -

Bloch Rubin ! ! a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of The

! ! ! ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! by! Ruth Frances !Bloch Rubin ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley ! Committee in charge: Professor Eric Schickler, Chair Professor Paul Pierson Professor Robert Van Houweling Professor Sean Farhang ! ! Fall 2014 ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! Copyright 2014 by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Eric Schickler, Chair The purpose of this dissertation is to supply a simple and synthetic theory to help us to understand the development and value of organized intraparty blocs. I will argue that lawmakers rely on these intraparty organizations to resolve several serious collective action and coordination problems that otherwise make it difficult for rank-and-file party members to successfully challenge their congressional leaders for control of policy outcomes. In the empirical chapters of this dissertation, I will show that intraparty organizations empower dissident lawmakers to resolve their collective action and coordination challenges by providing selective incentives to cooperative members, transforming public good policies into excludable accomplishments, and instituting rules and procedures to promote group decision-making. And, in tracing the development of intraparty organization through several well-known examples of party infighting, I will demonstrate that intraparty organizations have played pivotal — yet largely unrecognized — roles in critical legislative battles, including turn-of-the-century economic struggles, midcentury battles over civil rights legislation, and contemporary debates over national health care policy.