Building Blocks of Power: the Architectural Commissions and Decorative Projects of the Pucci Family in the Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

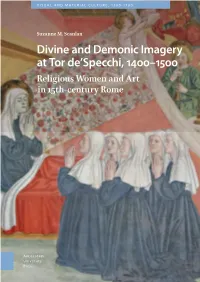

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Discovery Marche.Pdf

the MARCHE region Discovering VADEMECUM FOR THE TOURIST OF THE THIRD MILLENNIUM Discovering THE MARCHE REGION MARCHE Italy’s Land of Infinite Discovery the MARCHE region “...For me the Marche is the East, the Orient, the sun that comes at dawn, the light in Urbino in Summer...” Discovering Mario Luzi (Poet, 1914-2005) Overlooking the Adriatic Sea in the centre of Italy, with slightly more than a million and a half inhabitants spread among its five provinces of Ancona, the regional seat, Pesaro and Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno, with just one in four of its municipalities containing more than five thousand residents, the Marche, which has always been Italyʼs “Gateway to the East”, is the countryʼs only region with a plural name. Featuring the mountains of the Apennine chain, which gently slope towards the sea along parallel val- leys, the region is set apart by its rare beauty and noteworthy figures such as Giacomo Leopardi, Raphael, Giovan Battista Pergolesi, Gioachino Rossini, Gaspare Spontini, Father Matteo Ricci and Frederick II, all of whom were born here. This guidebook is meant to acquaint tourists of the third millennium with the most important features of our terri- tory, convincing them to come and visit Marche. Discovering the Marche means taking a path in search of beauty; discovering the Marche means getting to know a land of excellence, close at hand and just waiting to be enjoyed. Discovering the Marche means discovering a region where both culture and the environment are very much a part of the Made in Marche brand. 3 GEOGRAPHY On one side the Apen nines, THE CLIMATE od for beach tourism is July on the other the Adriatic The regionʼs climate is as and August. -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance

•••••••• ••• •• • .. • ••••---• • • - • • ••••••• •• ••••••••• • •• ••• ••• •• • •••• .... ••• .. .. • .. •• • • .. ••••••••••••••• .. eo__,_.. _ ••,., .... • • •••••• ..... •••••• .. ••••• •-.• . PETER MlJRRAY . 0 • •-•• • • • •• • • • • • •• 0 ., • • • ...... ... • • , .,.._, • • , - _,._•- •• • •OH • • • u • o H ·o ,o ,.,,,. • . , ........,__ I- .,- --, - Bo&ton Public ~ BoeMft; MA 02111 The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance ... ... .. \ .- "' ~ - .· .., , #!ft . l . ,."- , .• ~ I' .; ... ..__ \ ... : ,. , ' l '~,, , . \ f I • ' L , , I ,, ~ ', • • L • '. • , I - I 11 •. -... \' I • ' j I • , • t l ' ·n I ' ' . • • \• \\i• _I >-. ' • - - . -, - •• ·- .J .. '- - ... ¥4 "- '"' I Pcrc1·'· , . The co11I 1~, bv, Glacou10 t l t.:• lla l'on.1 ,111d 1 ll01nc\ S t 1, XX \)O l)on1c111c. o Ponrnna. • The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance New Revised Edition Peter Murray 202 illustrations Schocken Books · New York • For M.D. H~ Teacher and Prie11d For the seamd edillo11 .I ltrwe f(!U,riucu cerurir, passtJgts-,wwbly thOS<' on St Ptter's awl 011 Pnlladfo~ clmrdses---mul I lr,rvl' takeu rhe t>pportrmil)' to itJcorporate m'1U)1 corrt·ctfons suggeSLed to nu.• byfriet1ds mu! re11iewers. T'he publishers lwvc allowed mr to ddd several nt•w illusrra,fons, and I slumld like 10 rltank .1\ Ir A,firlwd I Vlu,.e/trJOr h,'s /Jelp wft/J rhe~e. 711f 1,pporrrm,ty /t,,s 11/so bee,r ft1ke,; Jo rrv,se rhe Biblfogmpl,y. Fc>r t/Jis third edUfor, many r,l(lre s1m1II cluu~J!eS lwvi: been m"de a,,_d the Biblio,~raphy has (IJICt more hN!tl extet1si11ely revised dtul brought up to date berause there has l,een mt e,wrmc>uJ incretlJl' ;,, i111eres1 in lt.1lim, ,1rrhi1ea1JrP sittr<• 1963,. wlte-,r 11,is book was firs, publi$hed. It sh<>uld be 110/NI that I haw consistc11tl)' used t/1cj<>rm, 1./251JO and 1./25-30 to 111e,w,.firs1, 'at some poiHI betwt.·en 1-125 nnd 1430', .md, .stamd, 'begi,miug ilJ 1425 and rnding in 14.10'. -

California State University, Northridge

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE The Palazzo del Te: Art, Power, and Giulio Romano’s Gigantic, yet Subtle, Game in the Age of Charles V and Federico Gonzaga A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies with emphases in Art History and Political Science By Diana L. Michiulis December 2016 The thesis of Diana L. Michiulis is approved: ___________________________________ _____________________ Dr. Jean-Luc Bordeaux Date ___________________________________ _____________________ Dr. David Leitch Date ___________________________________ _____________________ Dr. Margaret Shiffrar, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to convey my deepest, sincere gratitude to my Thesis Committee Chair, Dr. Margaret Shiffrar, for all of her guidance, insights, patience, and encourage- ments. A massive "merci beaucoup" to Dr. Jean-Luc Bordeaux, without whom completion of my Master’s degree thesis would never have been fulfilled. It was through Dr. Bordeaux’s leadership, patience, as well as his tremendous knowledge of Renaissance art, Mannerist art, and museum art collections that I was able to achieve this ultimate goal in spite of numerous obstacles. My most heart-felt, gigantic appreciation to Dr. David Leitch, for his leadership, patience, innovative ideas, vast knowledge of political-theory, as well as political science at the intersection of aesthetic theory. Thank you also to Dr. Owen Doonan, for his amazing assistance with aesthetic theory and classical mythology. I am very grateful as well to Dr. Mario Ontiveros, for his advice, passion, and incredible knowledge of political art and art theory. And many thanks to Dr. Peri Klemm, for her counsel and spectacular help with the role of "spectacle" in art history. -

MICROCARROS EUROPEUS Design E Mobilidade Sustentável

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES MICROCARROS EUROPEUS Design e Mobilidade sustentável Maria João Tavares dos Santos Gabriel Dissertação Mestrado em Design de Equipamento Especialização em Design de Produto Dissertação orientada pelo Professor Doutor Paulo Parra 2019 DECLARAÇÃO DE AUTORIA Eu, Maria João Tavares dos Santos Gabriel, declaro que a presente dissertação de mestrado intitulada “MICROCARROS EUROPEUS”, é o resultado da minha investigação pessoal e independente. O conteúdo é original e todas as fontes consultadas estão devidamente mencionadas na bibliografia ou outras listagens de fontes documentais, tal como todas as citações diretas ou indiretas têm devida indicação ao longo do trabalho segundo as normas académicas. O Candidato Lisboa, 31 de outubro de 2019 RESUMO A presente dissertação tem como tema “Microcarros Europeus – Design e Mobilidade sustentável”. O principal objetivo deste trabalho traduz-se na construção de uma leitura sistematizada do projeto e implementação de microcarros europeus ao longo do século XX, tendo em vista não só o esclarecimento/definição do próprio conceito, mas também a perceção do seu papel atual e futuro a nível da mobilidade urbana sustentável. Neste sentido, percorrem-se dimensões como o design específico dos veículos, antecessores, autores e empresas envolvidas, assim como o contexto socioeconómico inerente. Como metodologia, realizou-se uma pesquisa exaustiva em fontes bibliográficas e fontes on-line, para além de contactos diretos com colecionadores e especialistas na temática, através de fóruns de debate e participação em encontros e mostras nacionais. Os microcarros consistem em veículos motorizados, que surgiram na Europa após a Segunda Guerra Mundial, num contexto de escassez de recursos económicos, energéticos e de materiais de produção. -

1 the Political Philosophy of Niccolò Machiavelli Filippo Del Lucchese Table of Contents Preface Part I

The Political Philosophy of Niccolò Machiavelli Filippo Del Lucchese Table of Contents Preface Part I: The Red Dawn of Modernity 1: The Storm Part II: A Political Philosophy 2: The philosopher 3: The Discourses on Livy 4: The Prince 5: History as Politics 6: War as an art Part III: Legacy, Reception, and Influence 7: Authority, conflict, and the origin of the State (sixteenth-eighteenth centuries) 1 8: Nationalism and class conflict (nineteenth-twentieth centuries) Chronology Notes References Index 2 Preface Novel 84 of the Novellino, the most important collection of short stories before Boccaccio’s Decameron, narrates the encounter between the condottiere Ezzelino III da Romano and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II: It is recorded how one day being with the Emperor on horseback with all their followers, the two of them made a challenge which had the finer sword. The Emperor drew his sword from its sheath, and it was magnificently ornamented with gold and precious stones. Then said Messer Azzolino: it is very fine, but mine is finer by far. And he drew it forth. Then six hundred knights who were with him all drew forth theirs. When the Emperor saw the swords, he said that Azzolino’s was the finer.1 In the harsh conflict opposing the Guelphs and Ghibellines – a conflict of utter importance for the late medieval and early modern history of Italy and Europe – the feudal lord Ezzelino sends the Emperor a clear message: honours, reputation, nobility, beauty, ultimately rest on force. Gold is not important, good soldiers are, because good soldiers will find gold, not the contrary. -

Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530

PALPABLE POLITICS AND EMBODIED PASSIONS: TERRACOTTA TABLEAU SCULPTURE IN ITALY, 1450-1530 by Betsy Bennett Purvis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto ©Copyright by Betsy Bennett Purvis 2012 Palpable Politics and Embodied Passions: Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530 Doctorate of Philosophy 2012 Betsy Bennett Purvis Department of Art University of Toronto ABSTRACT Polychrome terracotta tableau sculpture is one of the most unique genres of 15th- century Italian Renaissance sculpture. In particular, Lamentation tableaux by Niccolò dell’Arca and Guido Mazzoni, with their intense sense of realism and expressive pathos, are among the most potent representatives of the Renaissance fascination with life-like imagery and its use as a powerful means of conveying psychologically and emotionally moving narratives. This dissertation examines the versatility of terracotta within the artistic economy of Italian Renaissance sculpture as well as its distinct mimetic qualities and expressive capacities. It casts new light on the historical conditions surrounding the development of the Lamentation tableau and repositions this particular genre of sculpture as a significant form of figurative sculpture, rather than simply an artifact of popular culture. In terms of historical context, this dissertation explores overlooked links between the theme of the Lamentation, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, codes of chivalric honor and piety, and resurgent crusade rhetoric spurred by the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Reconnected to its religious and political history rooted in medieval forms of Sepulchre devotion, the terracotta Lamentation tableau emerges as a key monument that both ii reflected and directed the cultural and political tensions surrounding East-West relations in later 15th-century Italy. -

Affective Criticism, Oral Poetics, and Beowulf's Fight with the Dragon

Oral Tradition, 10/1 (1995): 54-90 Affective Criticism, Oral Poetics, and Beowulf’s Fight with the Dragon Mark C. Amodio I Affective criticism, as it has been practiced over the last few years, has come to focus upon the reader’s (or audience’s) subjective experience of a given literary work.1 Rather than examining the text qua object, affective criticism (like all subjective criticism) has abandoned the objectivism and textual reification which lay at the heart of the New Critical enterprise, striving instead to lead “one away from the ‘thing itself’ in all its solidity to the inchoate impressions of a variable and various reader” (Fish 1980:42).2 Shifting the critical focus away from the text to the reader has engendered 1 Iser, one of the leading proponents of reader-based inquiry, offers the following succinct statement of the logic underlying his and related approaches: “[a]s a literary text can only produce a response when it is read, it is virtually impossible to describe this response without also analyzing the reading process” (1978:ix). Iser’s emphasis on the reader’s role and on the constitutive and enabling functions inherent in the act of reading are shared by many other modern theorists despite their radical differences in methodologies, aims, and conclusions. See especially Culler (1982:17-83), and the collections edited by Tompkins (1980) and Suleiman and Crosman (1980). 2 The New Criticism has generally warned against inscribing an idiosyncratic, historically and culturally determined reader into a literary text because doing so would lead to subjectivism and ultimately to interpretative chaos. -

Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi………………………………………

CBÜ SOSYAL BİLİMLER DERGİSİ Cilt:13, Sayı:3, Eylül 2015 Geliş Tarihi: 11.06.2015 Doi Number: 10.18026/cbusos.32235 Kabul Tarihi: 25.06.2015 RECONSTRUCTING THE HERO: REPRESENTATION OF LOYALTY IN LATE ANGLO-SAXON LITERATURE Şafak NEDİCEYUVA1 ABSTRACT Danish attacks on the British Isles in the 9th century had considerable political consequences for the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms reigning independently at the time. ‘The Great Heathen Army’, as the Anglo-Saxon called it, began a series of invasions in Britain and their advance was unstoppable until all Anglo-Saxon kingdoms but Wessex were conquered. Emerging as the rulers of only surviving Anglo-Saxon kingdom, Alfred and the subsequent monarchs of Wessex began a slow process of unifying the subjugated Anglo-Saxons under their banner and they desired to be acknowledged as the kings of England, rather than Wessex. By adapting traditional heroic values to contemporary political needs, literary works of this period similarly attempt to channel former tribal loyalties towards the monarch and propagandize absolute devotion to the survival and construction of ‘England’. This article discusses the ideological role literature played in late Anglo-Saxon era during the formation of England. Keywords: Anglo-Saxon, Viking, hero, heroic code, military organization. KAHRAMANIN YENİDEN KURGULANIŞI: GEÇ DÖNEM ANGLOSAKSON EDEBİYATI’NDA SADAKATİN TEMSİLİ ÖZ Dokuzuncu yüzyılda Britanya Adaları’na yapılan Viking saldırıları burada hüküm süren yedi bağımsız Anglosakson krallığı için önemli siyasi sonuçlar doğurmuştur. Anglosaksonların ‘Büyük Dinsiz Ordu’ adını verdikleri ordu Britanya’yı istila etmeye başlamış ve Wessex Krallığı dışında tüm diğer krallıklar yıkılana kadar durdurulamamıştır. Alfred ve ondan sonra tahta çıkan Wessex kralları ayakta kalan tek Anglosakson krallığının hükümdarları olarak Viking buyruğu altındaki Anglosaksonları kendi bayrakları altında bir araya getirmeyi ve Wessex değil İngiltere krallığı olarak tanınmayı arzulamışlardır. -

L'evoluzione Della Microcar: Da Semplice Motocicletta Con Il Tetto A

POLITECNICO DI MILANO Facoltà di Ingegneria Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Ingegneria Meccanica Elaborato del corso “Storia della Meccanica” Prof. Edoardo Rovida L’EVOLUZIONE DELL A MICROCAR: da semplice motociclett a con il tett o a solutric e dei problemi del traffico urbano e dell ’ecologia Autori: Agosti Diego Matr. 725703 Inglardi Stefano Matr. 720639 Vercesi Emanuele Matr. 725690 Anno Accademico 2008 -2009 Indice Introduzione . pag. 1 1945 VOLUGRAFO Bimbo 46 . pag. 5 1947 ALCA Volpe . » 10 1947 MI-VAL Mivalino 175 . » 14 1953 ISO Isetta . » 20 1958 ACMA Vespa 400 . » 30 1968 LAWIL Varzina . » 35 1969 CASALINI Sulky . » 41 Qualche curiosità . pag. 45 Uno sguardo all’Europa . » 50 Microcars: tra passato e futuro . » 54 Car-Sharing: una proposta di mobilità sostenibile . » 69 Bibliografia e siti internet visitati Bibliografia . pag. 73 I Poca ingegneria tanta fantasia Parola d’ordine: semplicità. Per costare poco, pesare poco, consumare poco. I progettisti, spesso provenienti dall’industria aeronautica, possono sbizzarrirsi, eliminando tutto il possibile: ruote, differenziali, ammortizzatori, retromarcia, porte. A volte persino il tetto. La scuola tedesca è la più prolifica per varietà di modelli, l’italiana la più originale mentre l’inglese è la più sconcertante. Le micro vetture esistono da desiderio di automobile. Niente a sempre, dagli albori della che vedere con le moderne city-car, motorizzazione; esemplari unici “seconde macchine” concepite per assemblati da costruttori dilettanti, districarsi nel traffico caotico delle modelli a volte geniali prodotti in città e spesso molto costose. Le piccole serie da modesti artigiani, microvetture hanno avuto ma anche raffinati progetti di sostanzialmente due periodi di forte importanti aziende costrette, nel espansione: negli anni 30, in seguito dopoguerra, a riconvertire la alla Grande Depressione e, produzione per cogliere le soprattutto, nel dopoguerra, quando opportunità offerte dal mercato.