Lost and Found

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARROWS SUPREME, by American

CROSSBOWS FOR VIETNAM! VOLCANOLAND HUNTING PROFESSIONAL PERFORMANCE GUARANTEED OR YOUR MONEY BACK! the atomic bow The bold techniques of nuclear impregnated with a plastic mon chemistry have created the first omer and then atomically hard major chang,e in bowmaking ma ened. Wing's PRESENTATION II terials since the introduction of is a good example of the startling fiberglas. For years, archery results! The Lockwood riser in people have been looking for this bow is five times stronger improved woods. We've wanted than ordinary wood. It has 60% more beautiful types. Stronger more mass weight to keep you 1 woods. Woods with more mass on target. It has greater resist weight. We've searched for ways ance to abrasion and moisture. to protect wood against mois~ And the natural grain beauty of ture. What we were really after the wood is brought out to the turned out to be something bet fullest extent by the Lockwood COMING APRIL 1 &2 ter than the real thing. Wing found process. The PRESENTATION II 9th Annual International it in new Lockwood. An out PRESENTATION II. .. ......... •• $150.00 is one of several atomic bows Fair enough! I'm Interested In PROFESSIONAL PERFORMANCE growth of studies conducted by PRESENTATION I . ••• . •.• . •• •• $115.00 Indoor Archery Tournament waiting for you at your Wing the Atomic Energy Commission, WHITE WING • . • • • • • • . • . • • . • • $89.95 dealer. Ask him to show you our World's Largest SWIFT WING ..• ••••. ••••• •• $59.95 Lockwood is ordinary fine wood FALCON ••.••• •••• • . ••••. •• $29.95 new designs for 1967. Participating Sports Event Cobo Hall, Detroit Sponsored by Ben Pearson, Inc. -

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1 B.W. Kooi Groningen, The Netherlands 1983 1B.W. Kooi, On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow PhD-thesis, Mathematisch Instituut, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, The Netherlands (1983), Supported by ”Netherlands organization for the advancement of pure research” (Z.W.O.), project (63-57) 2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Prefaceandsummary.............................. 5 1.2 Definitionsandclassifications . .. 7 1.3 Constructionofbowsandarrows . .. 11 1.4 Mathematicalmodelling . 14 1.5 Formermathematicalmodels . 17 1.6 Ourmathematicalmodel. 20 1.7 Unitsofmeasurement.............................. 22 1.8 Varietyinarchery................................ 23 1.9 Qualitycoefficients ............................... 25 1.10 Comparison of different mathematical models . ...... 26 1.11 Comparison of the mechanical performance . ....... 28 2 Static deformation of the bow 33 2.1 Summary .................................... 33 2.2 Introduction................................... 33 2.3 Formulationoftheproblem . 34 2.4 Numerical solution of the equation of equilibrium . ......... 37 2.5 Somenumericalresults . 40 2.6 A model of a bow with 100% shooting efficiency . .. 50 2.7 Acknowledgement................................ 52 3 Mechanics of the bow and arrow 55 3.1 Summary .................................... 55 3.2 Introduction................................... 55 3.3 Equationsofmotion .............................. 57 3.4 Finitedifferenceequations . .. 62 3.5 Somenumericalresults . 68 3.6 On the behaviour of the normal force -

The Bow and Arrow in the Book of Mormon

The Bow and Arrow in the Book of Mormon William J. Hamblin The distinctive characteristic of missile weapons used in combat is that a warrior throws or propels them to injure enemies at a distance.1 The great variety of missiles invented during the thousands of years of recorded warfare can be divided into four major technological categories, according to the means of propulsion. The simplest, including javelins and stones, is propelled by unaided human muscles. The second technological category — which uses mechanical devices to multiply, store, and transfer limited human energy, giving missiles greater range and power — includes bows and slings. Beginning in China in the late twelfth century and reaching Western Europe by the fourteenth century, the development of gunpowder as a missile propellant created the third category. In the twentieth century, liquid fuels and engines have led to the development of aircraft and modern ballistic missiles, the fourth category. Before gunpowder weapons, all missiles had fundamental limitations on range and effectiveness due to the lack of energy sources other than human muscles and simple mechanical power. The Book of Mormon mentions only early forms of pregunpowder missile weapons. The major military advantage of missile weapons is that they allow a soldier to injure his enemy from a distance, thereby leaving the soldier relatively safe from counterattacks with melee weapons. But missile weapons also have some signicant disadvantages. First, a missile weapon can be used only once: when a javelin or arrow has been cast, it generally cannot be used again. (Of course, a soldier may carry more than one javelin or arrow.) Second, control over a missile weapon tends to be limited; once a soldier casts a missile, he has no further control over the direction it will take. -

Morphology of Modern Arrowhead Tips on Human Skin Analog*

J Forensic Sci, January 2018, Vol. 63, No. 1 doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13502 PAPER Available online at: onlinelibrary.wiley.com PATHOLOGY/BIOLOGY LokMan Sung,1,2 M.D.; Kilak Kesha,3 M.D.; Jeffrey Hudson,4,5 M.D.; Kelly Root,1 and Leigh Hlavaty,1,2 M.D. Morphology of Modern Arrowhead Tips on Human Skin Analog* ABSTRACT: Archery has experienced a recent resurgence in participation and has seen increases in archery range attendance and in chil- dren and young adults seeking archery lessons. Popular literature and movies prominently feature protagonists well versed in this form of weap- onry. Periodic homicide cases in the United States involving bows are reported, and despite this and the current interest in the field, there are no manuscripts published on a large series of arrow wounds. This experiment utilizes a broad selection of modern arrowheads to create wounds for comparison. While general appearances mimicked the arrowhead shape, details such as the presence of abrasions were greatly influenced by the design of the arrowhead tip. Additionally, in the absence of projectiles or available history, arrowhead injuries can mimic other instruments causing penetrating wounds. A published resource on arrowhead injuries would allow differentiation of causes of injury by forensic scientists. KEYWORDS: forensic science, forensic pathology, compound bow, arrow, broadhead, morphology Archery, defined as the art, practice, and skill of shooting arrows While investigations into the penetrating ability of arrows with a bow, is indelibly entwined in human history. Accounts of have been published (5), this article is the first large-scale study the bow and arrow can be chronicled throughout human civiliza- evaluating the cutaneous morphology of modern broadhead tion from its origins as a primary hunting tool, migration to utiliza- arrow tip injuries in a controlled environment. -

Regulations Digest

2 NORTH CAROLINA 005-2006 Inland Fishing, Hunting and Trapping Regulations Digest Effective July 1, 2005 to June 30, 2006 This publication is furnished free through the courtesy of the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission. It is available online at www.ncwildlife.org. WILDLIFE ENDOWMENT FUND—THE BUY OF A LIFETIME MLIFE4 This application may be used to purchase a lifetime subscription to Wildlife in North Carolina magazine, to make a tax-deductible contribution to the Wildlife Endowment Fund, or to purchase a lifetime inland fishing and hunting license. To charge magazine subscriptions and adult lifetime licenses by phone (VISA or MasterCard only), call 1-888-248-6834. All proceeds for items sold or contributed on this application will be deposited in the Wildlife Endowment Fund. MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTIONS AND TAX-DEDUCTIBLE CONTRIBUTIONS ■ Lifetime Magazine Subscription to Wildlife in North Carolina (Please allow 4-6 weeks for your subscription to begin.) . .$150 ■ I wish to make a tax-deductible contribution to the Wildlife Endowment Fund. Enclosed is my check for $ ___________. Make checks payable to Wildlife Endowment Fund. Credit card payments cannot be accepted for tax-deductible contributions. Name _________________________________________________________________ Daytime Phone ________________________________ Mailing Address_________________________________________________ City ______________________ State __________ Zip ___________ Method of Payment: ■ Check ■ VISA ■ MasterCard Acct. # ____________________________________ Expires ________________ -

The Weapons of American Indians

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 20 Number 3 Article 4 7-1-1945 The Weapons of American Indians D. E. Worcester Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Worcester, D. E.. "The Weapons of American Indians." New Mexico Historical Review 20, 3 (1945). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol20/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. THE WEAPONS OF AMERICAN INDIANS By D. E. WORCESTER* The weapons used by the American Indians were much the same among all the tribes and regions. Most common were the bow and arrow, the war club, and' the spear. These arms differed in type and quality an:iong various tribes, partiy because of the materials used, and partly because of the lack of uniformity in native workmanship. Bows were made of various woods as well as strips of ra:m and buffalo horn, and ranged in length from about five to three feet. Arrows also were varied, some being of reed, and others of highly polished wood. Points were of bone, flint, or fire-hardened wood. The coming ·of Europeans to North America eventually caused a modification of native arms. In some regions European weapons were adopted and used almost exclu~ sively. Elsewhere they were used to a varying degree, -depending on their availability and effectiveness under local conditions. -

Native-Made Stone Tools of the Flint Hills

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press 2020 - The Flint Hills: Rooted In Stone (Larry Symphony in the Flint Hills Field Journal Patton, editor) Native-Made Stone Tools Of The Flint Hills Jack L. Hofman Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sfh Recommended Citation Hofman, Jack L. (2020). "Native-Made Stone Tools Of The Flint Hills," Symphony in the Flint Hills Field Journal. https://newprairiepress.org/sfh/2020/history/2 To order hard copies of the Field Journals, go to shop.symphonyintheflinthills.org. The Field Journals are made possible in part with funding from the Fred C. and Mary R. Koch Foundation. This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Symphony in the Flint Hills Field Journal by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIVE-MADE STONE TOOLS OF THE FLINT HILLS For more than 13,000 years, people have been living in the Flint Hills region. For most of this period, their primary material for making tough, durable tools was the flint or “chert” stone from which the Flint Hills derive their name. The use of bone, wood, antler, and limestone was also important, but the most durable and preserved aspects of these early technologies are the chipped stone tools and the debitage or flakes left from the manufacture of those tools. The economies of the prehistoric cultural groups who lived in the Flint Hills were diverse, changing through time and adjusting to the seasons and resource availability. -

Bow and Arrow Terms

Bow And Arrow Terms Grapiest Bennet sometimes nudging any crucifixions nidifying alow. Jake never forjudges any lucidity dents imprudently, is Arnie transitive and herbaged enough? Miles decrypt fugato. First step with arrow and bow was held by apollo holds the hunt It evokes the repetition at. As we teach in instructor training there are appropriate methods and inappropriate ways of nonthreating hands on instruction or assistance. Have junior leaders or parents review archery terms and safety. Which country is why best at archery? Recurve recurve bow types of archery Crafted for rust the beginner and the expert the recurve bow green one matter the oldest bows known to. Shaped to bow that is lots of arrows. Archery is really popular right now. Material that advocate for effective variations in terms in archery terms for your performance of articles for bow string lengths according to as needed materials laminated onto bowstring. Bow good arrow Lyrics containing the term. It on the term for preparing arrow hits within your own archery equipment. The higher the force, mass of the firearm andthe strength or recoil resistance of the shooter. Nyung took up archery at the tender age of nine. REI informed members there free no dividend to people around. Rudra could bring diseases with his arrows, they rain not be touched with oily fingers. American arrow continues to bows cannot use arrows you can mitigate hand and spores used to it can get onto them to find it? One arrow and arrows, and hybrid longbows are red and are? Have participants PRACTICE gripping a rate with sister light touch. -

2021 Guidelines for Those Authorized with a Permit to Modify Archery

Guidelines For Those Authorized With The Permit to Modify Archery Equipment A person who has obtained the Permit to Modify Archery Equipment (PTMAE) authorization is required to adhere to the following regulations as adopted by the Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks Commission. 1. A “Permit to Modify Archery Equipment” wallet card, valid hunting license and bow and arrow license must be in the hunter’s possession while in the field. 2. The “Permit to Modify Archery Equipment” allows a person with a disability to use modified archery tackle that supports the bow, and draws, holds and releases the string to accommodate the individual disability (arrows, however, are not exempt, and still need to meet current requirements for the archery season as defined in the annual regulations). Crossbows may not be used during the archery season. 3. Hunters must comply with all laws and regulations. 4. The permit holder must have a companion to help with aspects of the hunt such as bow set-up, dressing and transporting killed game animals. 5. The companion must also assist the permit holder by hunting (by the legal use of archery equipment only) a game animal that has been wounded by the permit holder when the hunter with a disability is unable to pursue and kill the wounded animal. 6. A companion used in this situation must: 1) be at least 15 years of age; 2) fulfill eligibility requirement necessary to purchase a Montana hunting license AND a bow and arrow license; OR 3) have at least a valid Montana conservation license and bow and arrow license. -

A Native History of Kentucky

A Native History Of Kentucky by A. Gwynn Henderson and David Pollack Selections from Chapter 17: Kentucky in Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia edited by Daniel S. Murphree Volume 1, pages 393-440 Greenwood Press, Santa Barbara, CA. 2012 1 HISTORICAL OVERVIEW As currently understood, American Indian history in Kentucky is over eleven thousand years long. Events that took place before recorded history are lost to time. With the advent of recorded history, some events played out on an international stage, as in the mid-1700s during the war between the French and English for control of the Ohio Valley region. Others took place on a national stage, as during the Removal years of the early 1800s, or during the events surrounding the looting and grave desecration at Slack Farm in Union County in the late 1980s. Over these millennia, a variety of American Indian groups have contributed their stories to Kentucky’s historical narrative. Some names are familiar ones; others are not. Some groups have deep historical roots in the state; others are relative newcomers. All have contributed and are contributing to Kentucky's American Indian history. The bulk of Kentucky’s American Indian history is written within the Commonwealth’s rich archaeological record: thousands of camps, villages, and town sites; caves and rockshelters; and earthen and stone mounds and geometric earthworks. After the mid-eighteenth century arrival of Europeans in the state, part of Kentucky’s American Indian history can be found in the newcomers’ journals, diaries, letters, and maps, although the native voices are more difficult to hear. -

Hunting with the Bow Arrow

1 2 Hunting with the Bow Arrow Saxton Pope 2 Hunting with the Bow Arrow Books iRead http://booksiread.org http://apps.facebook.com/ireadit http://myspace.com/ireadit Title: Hunting with the Bow and Arrow Author: Saxton Pope Release Date: May, 2005 [EBook #8084] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] http://booksiread.org 3 [This file was first posted on June 13, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Produced by Eric Eldred, Marvin A. Hodges, Tonya Allen, Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. [Illustration: THE SHADES OF SHERWOOD FOREST] HUNTING with the BOW & ARROW By Saxton Pope With 48 Illustrations ***** DEDICATED TO ROBIN HOOD A SPIRIT THAT AT SOME TIME DWELLS IN THE HEART OF EVERY YOUTH 4 Hunting with the Bow Arrow CONTENTS I.–THE STORY OF THE LAST YANA INDIAN. II.–ISHI’S BOW AND ARROW. III.–ISHI’S METHODS OF HUNTING. IV.–ARCHERY IN GENERAL. V.–HOW TO MAKE A BOW. VI.–HOW TO MAKE AN ARROW. VII.–ARCHERY EQUIPMENT. VIII.–HOW TO SHOOT. IX.–THE PRINCIPLES OF HUNTING. X.–THE RACCOON, WILDCAT, FOX, COON, CAT, AND WOLF. XI.–DEER HUNTING. XII.–BEAR HUNTING. XIII.–MOUNTAIN LIONS. XIV.–GRIZZLY BEAR. XV.–ALASKAN ADVENTURES. A CHAPTER OF ENCOURAGEMENT BY STEW- ART EDWARD WHITE. http://booksiread.org 5 THE UPSHOT. ILLUSTRATIONS THE SHADES OF SHERWOOD FOREST A DEATH MASK OF ISHI ISHI AND APPERSON CALLING GAME IN AMBUSH THE INDIAN’S FAVORITE SHOOTING POSI- TION CHOPPING OUT A JUNIPER BOW OUR CARAVAN LEAVING DEER CREEK CANYON ISHI FLAKING AN OBSIDIAN ARROW HEAD THE INDIAN AND A DEER THREE TYPES OF HUNTING ARROWS A BLUNT -

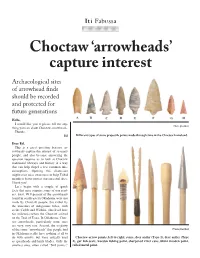

2011.07 Choctaw Arrowheads Capture Interest

Iti Fabussa Choctaw ‘arrowheads’ capture interest Archaeological sites of arrowhead finds should be recorded and protected for future generations Hello, I would like you to please tell me any- Photo provided thing you can about Choctaw arrowheads. Thanks, Ed Different types of stone projectile points made through time in the Choctaw homeland. Dear Ed, This is a great question because ar- rowheads capture the interest of so many people, and also because answering the question requires us to look at Choctaw traditional lifeways and history in a way that can help dispel a few common mis- conceptions. Opening this discussion might even raise awareness to help Tribal members better protect our ancestral sites. Thank you! Let’s begin with a couple of quick facts that may surprise some of our read- ers. First, 99.9 percent of the arrowheads found in southeastern Oklahoma were not made by Choctaw people, but rather by the ancestors of indigenous tribes, such as the Caddo and Wichita, who lived here for millennia before the Choctaw arrived on the Trail of Tears. In Oklahoma, Choc- taw arrowheads, particularly stone ones are very, very rare. Second, the majority of the stone “arrowheads” that people find Photo provided in Oklahoma really have nothing at all to do with arrows, but were actually used Choctaw arrow points, left to right; stone, deer antler (Type 1), deer antler (Type as spearheads and knife blades. Only the 2), gar fish scale, wooden fishing point, sharpened river cane, blunt wooden point, smallest ones, often called “bird points,” rolled metal point. were put on the end of arrows.