Cattle Breeds: Extinction Or Quasi-Extant?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revista Canchim 2010

2 3 4 CARTA CANCHIM Canchim Especial é uma publicação da Associação Brasileira de Criadores de Canchim Av. Francisco Matarazzo, 455 CEP: 05001-900 A PECUÁRIA Tel/Fax: (11) 3873-3099/3873-1891 www.canchim.com.br [email protected] E SEU GRANDE ABCCAN DESAFIO PRESIDENTE: Luiz Carlos Dias Fernandes DIRETOR ADMINISTRATIVO FINANCEIRO: Raphael Antonio Nogueira de Freitas DIRETOR DE MARKETING: Caro Leitor Carlos Alberto Meirelles de Azevedo DIRETOR DE EVENTOS E EXPOSIÇÕES: Hinderikus Jan Borg Um dos principais players no mercado internacional da carne, o Brasil tem um grande desafio: aumentar sua produtividade DIRETOR DE DESENVOLVIMENTO RACIAL E TÉCNICO: para atender à crescente demanda e, mais do que isso, melhorar Pedro Franklin Barbosa a qualidade. Afinal, o consumidor é cada vez mais exigente. DIRETOR REGIONAL NÚCLEO PARANAENSE: Cabe a nós, pecuaristas, investir em tecnologias que otimizem a Francisco Fernando Fontana produção e responda à altura a tamanho desafio num mercado DIRETOR REGIONAL tão competitivo. NÚCLEO BRASIL CENTRAL: Euclides Henriques Morais Filho Uma delas é a utilização de um gado rústico, altamente produtivo DIRETOR REGIONAL NÚCLEO MATO GROSSO DO SUL: e que oferece carne de qualidade superior, exatamente como é o Jorge T. S. Pereira Canchim. É para mostrar tudo isso para você que desenvolvemos SUPERINTENDENTE REGISTRO GENEALÓGICO: o conteúdo dessa revista. Luiz Roberto Belém Silveira Lopes ASSESSORIA DE EVENTOS: Nossa matéria de capa, sobre cruzamento industrial, pretende Mauro de Carvalho Filho clarificar a vocação maior de nossa raça: o cruzamento com outras raças. Nas reportagens sobre ganho de peso e rusticidade EXPEDIENTE - grandes atributos do Canchim - mostraremos como o gado é REDAÇÃO E EDIÇÃO: imbatível em condições severas. -

"First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

Country Report of Australia for the FAO First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1 ASSESSING THE STATE OF AGRICULTURAL BIODIVERSITY THE FARM ANIMAL SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA.................................................................................7 1.1 OVERVIEW OF AUSTRALIAN AGRICULTURE, ANIMAL PRODUCTION SYSTEMS AND RELATED ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY. ......................................................................................................7 Australian Agriculture - general context .....................................................................................7 Australia's agricultural sector: production systems, diversity and outputs.................................8 Australian livestock production ...................................................................................................9 1.2 ASSESSING THE STATE OF CONSERVATION OF FARM ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY..............10 Major agricultural species in Australia.....................................................................................10 Conservation status of important agricultural species in Australia..........................................11 Characterisation and information systems ................................................................................12 1.3 ASSESSING THE STATE OF UTILISATION OF FARM ANIMAL GENETIC RESOURCES IN AUSTRALIA. ........................................................................................................................................................12 -

Pho300007 Risk Modeling and Screening for Brcai

?4 101111111111 PHO300007 RISK MODELING AND SCREENING FOR BRCAI MUTATIONS AMONG FILIPINO BREAST CANCER PATIENTS by ALEJANDRO Q. NAT09 JR. A Master's Thesis Submitted to the National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology College of Science University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City As Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY March 2003 In memory of my gelovedmother Mrs. josefina Q -Vato who passedaway while waitingfor the accomplishment of this thesis... Thankyouvery inuchfor aff the tremendous rove andsupport during the beautifil'30yearstfiatyou were udth me... Wom, you are he greatest! I fi)ve you very much! .And.. in memory of 4 collaborating 6reast cancerpatients who passedaway during te course of this study ... I e.Vress my deepest condolence to your (overtones... Tou have my heartfeligratitude! 'This tesis is dedicatedtoa(the 37 cofla6oratingpatients who aftruisticaffyjbinedthisstudyfor te sake offuture generations... iii This is to certify that this master's thesis entitled "Risk Modeling and Screening for BRCAI Mutations among Filipino Breast Cancer Patients" and submitted by Alejandro Q. Nato, Jr. to fulfill part of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology was successfully defended and approved on 28 March 2003. VIRGINIA D. M Ph.D. Thesis Ad RIO SUSA B. TANAEL JR., M.Sc., M.D. Thesis Co-.A. r Thesis Reader The National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology endorses acceptance of this master's thesis as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. -

Crossbreeding Systems for Small Beef Herds

~DMSION OF AGRICULTURE U~l_}J RESEARCH &: EXTENSION Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Arkansas System FSA3055 Crossbreeding Systems for Small Beef Herds Bryan Kutz For most livestock species, Hybrid Vigor Instructor/Youth crossbreeding is an important aspect of production. Intelligent crossbreed- Generating hybrid vigor is one of Extension Specialist - the most important, if not the most ing generates hybrid vigor and breed Animal Science important, reasons for crossbreeding. complementarity, which are very important to production efficiency. Any worthwhile crossbreeding sys- Cattle breeders can obtain hybrid tem should provide adequate levels vigor and complementarity simply by of hybrid vigor. The highest level of crossing appropriate breeds. However, hybrid vigor is obtained from F1s, sustaining acceptable levels of hybrid the first cross of unrelated popula- vigor and breed complementarity in tions. To sustain F1 vigor in a herd, a a manageable way over the long term producer must avoid backcrossing – requires a well-planned crossbreed- not always an easy or a practical thing ing system. Given this, finding a way to do. Most crossbreeding systems do to evaluate different crossbreeding not achieve 100 percent hybrid vigor, systems is important. The following is but they do maintain acceptable levels a list of seven useful criteria for evalu- of hybrid vigor by limiting backcross- ating different crossbreeding systems: ing in a way that is manageable and economical. Table 1 (inside) lists 1. Merit of component breeds expected levels of hybrid vigor or het- erosis for several crossbreeding sys- 2. Hybrid vigor tems. 3. Breed complementarity 4. Consistency of performance Definitions 5. Replacement considerations hybrid vigor – an increase in 6. -

Characterization of Commercial Cuts from the Crioulo Lageano Beef Breed

Food Sci. Technol. Res., 18 (6), 761–768, 2012 Characterization of Commercial Cuts from the Crioulo Lageano Beef Breed 1 2 3 3 Marina Leite Mitterer-Daltoé , Alexandre Floriani raMos , Edison Martins , Vera Maria Villamil Martins and 1* Maria Isabel Queiroz 1 Federal University of Rio Grande, RS, Brazil 2 Embrapa Genetic Resources and Biotechnology, DF, Brazil 3 State University of Santa Catarina, SC, Brazil Received February 8, 2012; Accepted July 31, 2012 This work aimed to study the features of Crioulo Lageano beef cattle and compare them with those of the Nellore, the main commercial breed of Brazil. Twelve cattle each of the Nellore and Crioulo Lageano were evaluated for carcass characteristics, muscle:carcass ratio and chemical composition of commercial cuts: topside, rum cap, eye round, sirloin, tenderloin and rib eye. In this study, the meat of Crioulo Lag- eano exhibited a higher marbling score than that of Nellore. Rib eye and sirloin cuts of Crioulo Lageano stood out due to their weight and intramuscular fat content. The following variables explained 69.4% of the characteristics of the Crioulo Lageano beef as determined by principal components analysis (PCA): hot carcass weight, hindquarter, forequarter, pistola, topside, rum cap, eye round, sirloin, tenderloin, rib eye and dressing. The muscle:carcass ratio and PCA values demonstrated the adaptability of the Crioulo Lageano cattle to the southern Santa Catarina Plateau. Keywords: beef, Bos indicus, Bos Taurus, carcass, chemical composition Introduction tury. Although more productive, these breeds did not have Brazil is the largest producer and second-largest exporter adaptive traits such as resistance to ectoparasites found in of beef in the world (MAPA, 2010). -

Evaluation of Nelore, Canchim, Santa Gertrudis, Holstein, Brown Swiss and Caracu As Sire Breeds in Matings with Nelore Cows

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln 3rd World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production Animal Science Department 1986 Evaluation of Nelore, Canchim, Santa Gertrudis, Holstein, Brown Swiss and Caracu as Sire Breeds in Matings with Nelore Cows. Effects on Progeny Growth, Carcass Traits and Crossbred Productivity A. G. Razook Universidade de Sao Paulo P. R. Leme Universidade de Sao Paulo I. U. Packer Universidade de Sao Paulo A. Luchiari Filho Universidade de Sao Paulo R. F. Nordos Universidade de Sao Paulo Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/wcgalp See next page for additional authors Part of the Animal Sciences Commons Razook, A. G.; Leme, P. R.; Packer, I. U.; Filho, A. Luchiari; Nordos, R. F.; Trovo, J. B.; Capelozza, C. N. Z.; Pires, F. L.; Nascimento, J.; Barbosa, C.; Coutinho, J. L. B.; and Oliveira, W. J., "Evaluation of Nelore, Canchim, Santa Gertrudis, Holstein, Brown Swiss and Caracu as Sire Breeds in Matings with Nelore Cows. Effects on Progeny Growth, Carcass Traits and Crossbred Productivity" (1986). 3rd World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production. 33. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/wcgalp/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Animal Science Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in 3rd World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors A. G. Razook, P. R. Leme, I. U. Packer, A. Luchiari Filho, R. F. Nordos, J. B. Trovo, C. N. Z. -

Are Adaptations Present to Support Dairy Cattle Productivity in Warm Climates?

J. Dairy Sci. 94 :2147–2158 doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3962 © American Dairy Science Association®, 2011 . Invited review: Are adaptations present to support dairy cattle productivity in warm climates? A. Berman 1 Department of Animal Science, Hebrew University, Rehovot 76100, Israel ABSTRACT breeds did not increase heat dissipation capacity, but rather diminished climate-induced strain by decreas- Environmental heat stress, present during warm ing milk production. The negative relationship between seasons and warm episodes, severely impairs dairy reproductive efficiency and milk yield, although rela- cattle performance, particularly in warmer climates. tively low, also appears in Zebu cattle. This association, It is widely viewed that warm climate breeds (Zebu coupled with limited feed intake, acting over millennia, and Sanga cattle) are adapted to the climate in which probably created the selection pressure for a low milk they evolved. Such adaptations might be exploited for production in these breeds. increasing cattle productivity in warm climates and Key words: heat stress , adaptations , dairy productiv- decrease the effect of warm periods in cooler climates. ity The literature was reviewed for presence of such ad- aptations. Evidence is clear for resistance to ticks and INTRODUCTION tick-transmitted diseases in Zebu and Sanga breeds as well as for a possible development of resistance to Environmental stress has a severe effect on the pro- ticks in additional breeds. Development of resistance ductivity of animals and, in particular, on that of dairy to ticks demands time; hence, it needs to be balanced cattle. Environmental stress is a stumbling block for with potential use of insecticides or vaccination. -

TCC Rodrigo 07.12.15

1 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS AGRÁRIAS CURSO DE ZOOTECNIA RODRIGO SOPRANO NOVILHO PRECOCE: SUGESTÕES DE INOVAÇÃO INCREMENTAL FLORIANÓPOLIS - SC 2015 2 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS AGRÁRIAS CURSO DE ZOOTECNIA RODRIGO SOPRANO NOVILHO PRECOCE: SUGESTÕES DE INOVAÇÃO INCREMENTAL Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado como exigência para obtenção do Diploma de Graduação em Zootecnia da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Orientador: Prof. Dr Sergio Augusto Ferreira Quadros FLORIANÓPOLIS – SC 2015 3 4 5 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço primeiramente a minha família, que nos momentos difíceis sempre se mostraram presentes para superá-los, Agradeço aos meus pais, Nilson Soprano e Sandra Bortolotto Soprano, ao meu irmão Ricardo Luiz Soprano e familiares, que sempre incentivaram e não mediram esforços para a conclusão do meu ensino superior, mas principalmente a minha mulher Andreliza Correa e minha filha Júlia Soprano que suportaram a saudade durante o período de estudo e mesmo assim não deixaram de apoiar. Gostaria de deixar meus agradecimentos a todos os colegas da CIDASC, em principal ao Sr. Sergio Silva Borges, onde consegui todo o material necessário para a execução deste trabalho, alem de fazer grandes amizades. Agradecer também aos colegas de faculdade que sempre estiveram juntos e se tornaram grandes amigos para a vida. 6 RESUMO O presente trabalho tem como objetivo, sugerir alterações de inovações incrementais para o Programa Novilho Precoce de Santa Catarina, sugestões estas que trarão melhorias a um processo já existente com o intuito de aperfeiçoar seu desempenho sem interferir no seu objetivo. O Programa Novilho Precoce foi iniciado em Santa Catarina em 28.07.1993, a partir da Legislação Estadual Nº 9.183 que tinha como objetivo criar o Programa de Apoio à Criação de Gado para Abate Precoce (PACGAP), incentivando pecuaristas que levassem seus animais ao abate precocemente para então receber uma bonificação conforme classificação e tipificação das carcaças. -

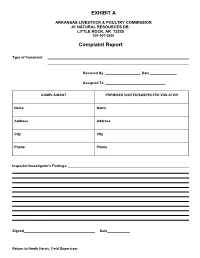

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

ACE Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA August 13, 2021 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes .................................................................................................................................................... 4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes ........................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ................................................................................................... 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes .......................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers ........................................................................ 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ............................................................................................................................. 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers ........................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure ...................................................................................................................................... 30 PG05 – Scientific Species Code ........................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ........................................................................................................... -

Genetic Diversity Analysis of the Uruguayan Creole Cattle Breed Using Microsatellites and Mtdna Markers

Genetic diversity analysis of the Uruguayan Creole cattle breed using microsatellites and mtDNA markers E. Armstrong1*, A. Iriarte1,3*, A.M. Martínez2, M. Feijoo3, J.L. Vega-Pla4, J.V. Delgado2 and A. Postiglioni1 1Área Genética, Departamento de Genética y Mejora Animal, Facultad de Veterinaria, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay 2Departamento de Genética, Facultad de Veterinaria, Universidad de Córdoba, Córdoba, España 3Laboratorio de Evolución, Facultad de Ciencias (UDELAR), Montevideo, Uruguay 4Laboratorio de Investigación Aplicada, Cría Caballar de las Fuerzas Armadas, Córdoba, España *These authors contributed equally to this study. Corresponding authors: E. Armstrong / A. Iriarte E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 12 (2): 1119-1131 (2013) Received July 7, 2012 Accepted October 10, 2012 Published April 10, 2013 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/2013.April.10.7 ABSTRACT. The Uruguayan Creole cattle population (N = 600) is located in a native habitat in south-east Uruguay. We analyzed its genetic diversity and compared it to other populations of American Creole cattle. A random sample of 64 animals was genotyped for a set of 17 microsatellite loci, and the D-loop hyper-variable region of mtDNA was sequenced for 28 calves of the same generation. We identified an average of 5.59 alleles per locus, with expected heterozygosities between 0.466 and 0.850 and an expected mean heterozygosity of 0.664. The polymorphic information content ranged from 0.360 to 0.820, and the global FIS index was 0.037. The D-loop analysis revealed three haplotypes (UY1, UY2 and UY3), belonging to the European Genetics and Molecular Research 12 (2): 1119-1131 (2013) ©FUNPEC-RP www.funpecrp.com.br E. -

Ip in GEOGRAPHY

Development and Future Prospects of Dairy and Dairy Industry of Uttar Pradesh DISSEF'vTATlON SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF fSasiter of $btlosiop|ip IN GEOGRAPHY BY RAIS SHIREEN Under the Supervision of Dr. S. M. Shahid Hasan DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH, (INDIA) 10 8 8 DS1445 ^\ / /v d^iy Fhone: 5 6 6 1 DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY ALtGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSiT'. ALJGARH January 28, 1988 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation on "Development and Future Prospects of Dairy and Dairy Industry of Uttar Pradesh" has written by Ms, Rais Shireen under my supervision and that is fit for submission for evaluation as partial fulfilment of the requirements of her M.Phil Programme in Geography. ,; ^, t v^' /vj^ (S.M.Shahid Hasan) Supervisor ACKKOV/LEDGrMSNT I wish to offer my profound gratitude to my Supervisor Dr.S.M, Shahid Hasan, for his excellent guidance, keen interest, constant support and constructive criticism throughout the course of this study, I am highly grateful to Prof. Abdul Aziz, Chairman, Department of Geography for the generous availability of all kinds of research facilities, 1 om also grateful to Prof. Mehdi Raza for his persistent interest and encouragement at all levels, My sincere thanks are also due to all my teachers and colleagues for many helpful discussions and their continuous help. Words fall short to offer my gratefulness to my parents, always a source of inspiration, for their encouragements throughout. Lastly but not least I am highly thankful to my husband, Mr. Rais, for his patience and amicable cooperation, Mr. Najrauddin and Mrs.