© 2012 Katrin Polak-Springer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Über Gegenwartsliteratur About Contemporary Literature

Leseprobe Über Gegenwartsliteratur Interpretationen und Interventionen Festschrift für Paul Michael Lützeler zum 65. Geburtstag von ehemaligen StudentInnen Herausgegeben von Mark W. Rectanus About Contemporary Literature Interpretations and Interventions A Festschrift for Paul Michael Lützeler on his 65th Birthday from former Students Edited by Mark W. Rectanus AISTHESIS VERLAG ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Bielefeld 2008 Abbildung auf dem Umschlag: Paul Klee: Roter Ballon, 1922, 179. Ölfarbe auf Grundierung auf Nesseltuch auf Karton, 31,7 x 31,1 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. © VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn 2008 Bibliographische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. © Aisthesis Verlag Bielefeld 2008 Postfach 10 04 27, D-33504 Bielefeld Satz: Germano Wallmann, www.geisterwort.de Druck: docupoint GmbH, Magdeburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten ISBN 978-3-89528-679-7 www.aisthesis.de Inhaltsverzeichnis/Table of Contents Danksagung/Acknowledgments ............................................................ 11 Mark W. Rectanus Introduction: About Contemporary Literature ............................... 13 Leslie A. Adelson Experiment Mars: Contemporary German Literature, Imaginative Ethnoscapes, and the New Futurism .......................... 23 Gregory W. Baer Der Film zum Krug: A Filmic Adaptation of Kleist’s Der zerbrochne Krug in the GDR ......................................................... -

Budget Increase Will Keep Deficit in Check

Campagne de souscription Capital Campaign de l'Urnversite Concordia Concordia University ~DJ Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec Volume 8, Number 25 March 28, 1985 Budget increase will keep deficit in check by Barbara Verity million for resea:rch grants; ast week's announce and $2.3 million for computer ment by Higher Educa training. These figures total Ltion, Science and $73.9 million; however, $3.6 Technology Minister Yves million will go from the Berube that the government universities back to the budget for universities will in government as income from crease by $70.3 million this fees collected from foreign year is good news for Concor students. This brings the dia, says Rector Patrick Ken figure back to $70.3 million. niff. However, the major ef Kenniff pointed out the im fect here will simply be to keep portance to Concordia of the this year's deficit from grow $36. 7 million that will cover ing. the cost of increased The government move enrolments in all seven of creates a relatively good situa Quebec's universities. In tion for I 985-86, but it doesn't previous years, if a university solve the problem of Concor increased its student enrol dia's deficit, expected to reach ment no new government $10 million by the end of this funds were received for these year. The Budget Cutback students. Funds had to be Task Force formed in taken from other universities December still must find ways where enrolment had not in of trimming $3 million from creased and re-distributed to The library centre at the west end campus will consist of the Vanier library, which will be doubled the budget to cover the the growing universities. -

Martin Walsers Doppelte Buchführung. Die Konstruktion Und Die Dekonstruktion Der Nationalen Identität in Seinem

Martin Walsers doppelte Buchführung. Die Konstruktion und die Dekonstruktion der nationalen Identität in seinem Spätwerk Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr.phil.) an der Universität Konstanz Fachbereich Literaturwissenschaft Geisteswissenschaftliche Sektion vorgelegt von Jakub Novák Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 15. Juli 2002 Referent: Prof. Dr. Gerhart von Graevenitz Referentin: Prof. Dr. Almut Todorow Danksagung Ich möchte es nicht versäumen, Herrn Prof. Dr. Gerhart von Graevenitz und Frau Prof. Dr. Almut Todorow für die Unterstützung Dank abzustatten, die sie mir während meines Promotionsstudiums an der Universität Konstanz gewährt haben. Mein herzlicher Dank gebührt des weiteren Dr. Hermann Kinder, mit dem ich einige Aspekte dieser Arbeit erörtern konnte. Bei dem Deutschen Akademischen Austauschdienst (DAAD) in Bonn möchte ich mich bei dieser Gelegenheit für die großzügige finanzielle Förderung bedanken, die die Entstehung dieser Dissertation allererst ermöglicht hat. 2 Ana-Maria gewidmet 3 Inhalt „With Walser the situation is less clear.“ Zum Erkenntnisinteresse dieser Arbeit 6 1. Die Konstruktion und die Dekonstruktion der nationalen Identität in Martin Walsers Essays, Reden und Interviews seit 1977 1. 1. Die ästhetische Konstruktion der personalen Identität 1. 1. 1. Die ästhetische Lebensphilosophie 10 1. 1. 2. Das Schöne, das Wahre, das Gute? 27 1. 1. 3. Zur Topik der Intellektuellenkritik I 32 1. 1. 4. Das Gewissen 37 1. 1. 5. Die Medienkritik 1. 1. 5. 1. Die lebensphilosophische Begründung der Medienkritik 47 1. 1. 5. 2. Die semiotische Begründung der Medienkritik 52 1. 2. Die Nationalisierung der personalen Identität 1. 2. 1. Die ontologisch gegebene Nation 57 1. 2. 2. Zur Topik der Intellektuellenkritik II 64 1. -

Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination EDITED BY TARA FORREST Amsterdam University Press Alexander Kluge Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination Edited by Tara Forrest Front cover illustration: Alexander Kluge. Photo: Regina Schmeken Back cover illustration: Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © T. Forrest / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustra- tions reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Alexander Kluge …and in memory of Miriam Hansen Table of Contents Introduction Editor’s Introduction Tara Forrest The Stubborn Persistence of Alexander Kluge Thomas Elsaesser Film, Politics and the Public Sphere On Film and the Public Sphere Alexander Kluge Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to G I A Miriam Hansen ‘What is Different is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge Heide -

GESAMTARBEIT Kulturtechniken Des Kollektiven Bei Alexander Kluge

Jens Grimstein GESAMTARBEIT Kulturtechniken des Kollektiven bei Alexander Kluge Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Philosophie und Geisteswissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin Gutachterinnen und Gutachter: Erstgutachterin: Frau Prof. Dr. Irene Albers Zweitgutachter: Herr PD Dr. Wolfram Ette Tag der Disputation: 03. Juli 2019 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. Einleitung ............................................................................ 2 2. Begriffe (Theorie) ............................................................. 12 2.1. Kollektive................................................................................ 12 2.2. Kulturtechniken ...................................................................... 25 2.3. Arbeit ...................................................................................... 40 2.4. Gesamtarbeit ........................................................................... 47 3. Kluges Theoriearbeit (Theoros) ........................................ 57 3.1. Kluge und die Theorie ............................................................ 58 3.2. Kluge und die Kollektive ........................................................ 64 3.3. Kluge und die Kulturtechniken ............................................... 66 3.4. Die Kritische Theorie zwischen Aufklärung und Theorie der Kulturtechnik ............................................... 85 4. Medien (Textilia) .............................................................. 92 4.1. Zivilisation, Turm, Stadt -

Wenders Has Had Monumental Influence on Cinema

“WENDERS HAS HAD MONUMENTAL INFLUENCE ON CINEMA. THE TIME IS RIPE FOR A CELEBRATION OF HIS WORK.” —FORBES WIM WENDERS PORTRAITS ALONG THE ROAD A RETROSPECTIVE THE GOALIE’S ANXIETY AT THE PENALTY KICK / ALICE IN THE CITIES / WRONG MOVE / KINGS OF THE ROAD THE AMERICAN FRIEND / THE STATE OF THINGS / PARIS, TEXAS / TOKYO-GA / WINGS OF DESIRE DIRECTOR’S NOTEBOOK ON CITIES AND CLOTHES / UNTIL THE END OF THE WORLD ( CUT ) / BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB JANUSFILMS.COM/WENDERS THE GOALIE’S ANXIETY AT THE PENALTY KICK PARIS, TEXAS ALICE IN THE CITIES TOKYO-GA WRONG MOVE WINGS OF DESIRE KINGS OF THE ROAD NOTEBOOK ON CITIES AND CLOTHES THE AMERICAN FRIEND UNTIL THE END OF THE WORLD (DIRECTOR’S CUT) THE STATE OF THINGS BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Wim Wenders is cinema’s preeminent poet of the open road, soulfully following the journeys of people as they search for themselves. During his over-forty-year career, Wenders has directed films in his native Germany and around the globe, making dramas both intense and whimsical, mysteries, fantasies, and documentaries. With this retrospective of twelve of his films—from early works of the New German Cinema Alice( in the Cities, Kings of the Road) to the art-house 1980s blockbusters that made him a household name (Paris, Texas; Wings of Desire) to inquisitive nonfiction looks at world culture (Tokyo-ga, Buena Vista Social Club)—audiences can rediscover Wenders’s vast cinematic world. Booking: [email protected] / Publicity: [email protected] janusfilms.com/wenders BIOGRAPHY Wim Wenders (born 1945) came to international prominence as one of the pioneers of the New German Cinema in the 1970s and is considered to be one of the most important figures in contemporary German film. -

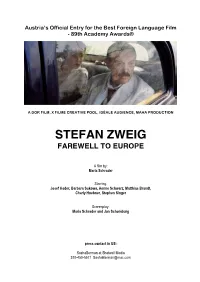

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae ROMUALD KARMAKAR DIRECTOR – PRODUCER Pantera Film GmbH Uhlandstrasse 160 10719 Berlin, Germany Ph +493068810141 [email protected] www.romuald-karmakar.de BACKGROUND Born 1965 in Wiesbaden, Germany. French citizen. Lives and works in Berlin. EDUCATION Higher education entrance qualification (Abitur), Oskar-von-Miller-Gymnasium, Munich (Germany), 1984 HONORS AND AWARDS – Best Music Documentary, DENK ICH AN DEUTSCHLAND IN DER NACHT, Dock of the Bay 2018, Festival de Cine Documental Musical de Donostia/San Sebastián – Preis der deutschen Filmkritik 2017, "Beste Musik“, DENK ICH AN DEUTSCHLAND IN DER NACHT – Invitation to “documenta 14”, Athens / Kassel, 2017 – Member of the International Jury of the 7th DMZ Int. Documentary Film Festival, Korea, 2015 – Member of the artistic board to join Chris Dercon (Tate Modern), the director to-be of Volksbühne, Berlin, 2015 – DEFA-Foundation Award for „Outstanding Achievement in German Film“, 2014 – Tutor of a student’s closing project (“Temperatur des Willens”, Peter Baranowski, 2017) at the University of Film and Television, Munich, SS 2014 – Seminar on „Filming Controversial Persons“ (Umstrittene Personen filmen) at the University of Film and Television, Munich, WS 2013/14 – Invitation to the German Pavilion at the Art Biennale in Venice, 2013, together with Ai Weiwei, Santu Mofokeng and Dayanita Singh – Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 2012-2013 – Member of the Jury for the art competition of „NS-Dokumentationszentrum München“, 2012 – Jury President of „Dialogue en perspective“ in the Perspektive Deutsches Kino section of the Berlin Int. Film Festival, 2011 – Retrospective at the Jeonju Int. Film Festival, Korea, 2010 – Retrospective at the Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, 2010 CV. -

A Film by MICHAEL HANEKE East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP BLOCK KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

A film by MICHAEL HANEKE East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP BLOCK KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Ziggy Kozlowski Lindsay Macik 853 7th Avenue, #3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax X FILME CREATIVE POOL, LES FILMS DU LOSANGE, WEGA FILM, LUCKY RED present THE WHITE RIBBON (DAS WEISSE BAND) A film by MICHAEL HANEKE A SONY PICTURES CLASSICS RELEASE US RELEASE DATE: DECEMBER 30, 2009 Germany / Austria / France / Italy • 2H25 • Black & White • Format 1.85 www.TheWhiteRibbonmovie.com Q & A WITH MICHAEL HANEKE Q: What inspired you to focus your story on a village in Northern Germany just prior to World War I? A: I wanted to present a group of children on whom absolute values are being imposed. What I was trying to say was that if someone adopts an absolute principle, when it becomes absolute then it becomes inhuman. The original idea was a children’s choir, who want to make absolute principles concrete, and those who do not live up to them. Of course, this is also a period piece: we looked at photos of the period before World War I to determine costumes, sets, even haircuts. I wanted to describe the atmosphere of the eve of world war. There are countless films that deal with the Nazi period, but not the pre-period and pre-conditions, which is why I wanted to make this film. -

Filmprogramm Zur Ausstellung Mo., 1. Juni, 19.30 Uhr Warnung Vor Einer

Filmprogramm zur Ausstellung Mo., 1. Juni, 19.30 Uhr Warnung vor einer heiligen Nutte Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1970 Mit Lou Castel, Eddie Constantine, Hanna Schygulla, Marquard Bohm DCP OmE 103 Minuten Mo., 8. Juni, 19.30 Uhr Händler der vier Jahreszeiten Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1971 Mit Hans Hirschmüller, Irm Hermann DCP OmE 89 Minuten Mo., 15. Juni, 19.30 Uhr Die bitteren Tränen der Petra von Kant Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1972 Mit Margit Carstensen, Hanna Schygulla, Irm Hermann DCP OmE 124 Minuten Mo., 22. Juni, 19 Uhr Welt am Draht Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1973 Mit Klaus Löwitsch, Mascha Rabben, Karl-Heinz Vosgerau, Ivan Desny, Barbara Valentin DCP OmE 210 Minuten Mo., 29. Juni, 19.30 Uhr Angst essen Seele auf Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1974 Mit Brigitte Mira, El Hedi Ben Salem, Barbara Valentin, Irm Hermann DCP OmE 93 Minuten Mo., 6. Juli, 19.30 Uhr Martha Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1974 Mit Margit Carstensen, Karlheinz Böhm 35mm 116 Minuten Mo., 13. Juli, 19.30 Uhr Fontane Effi Briest Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1974 Mit Hanna Schygulla, Wolfgang Schenck, Karlheinz Böhm DCP OmE 141 Minuten Mo., 20. Juli, 19.30 Uhr Faustrecht der Freiheit Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1975 Mit Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Peter Chatel, Karlheinz Böhm DCP OmE 123 Minuten Mo., 27. Juli, 19.30 Uhr Chinesisches Roulette Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1976 Mit Margit Carstensen, Anna Karina DCP OmE 86 Minuten Mo., 3. August, 19.30 Uhr Die Ehe der Maria Braun Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1978 Mit Hanna Schygulla, Klaus Löwitsch, Ivan Desny, Gottfried John DCP OmE 120 Minuten Mo., 10. -

FSFF Magazin

fsff - magazin WIE ENTSCHEIDEN WIR UNS? Gedanken zum 11. Fünf Seen Filmfestival Liebe FilmfreundInnen! Mit Ihnen fiebere ich den mehr als 400 Vorstel - Ihnen allen gemein ist der künstlerische Blick zensur in der heutigen Welt im Vergleich zur lungen des 11. Fünf Seen Filmfestivals entge - auf die jeweilige Welt –in einer solchen Vielzahl Zensur in diktatorischen Staaten, ohne diese gen. Ein Jahr lang haben mein Team und ich an und Reichhaltigkeit während der zehn Festival - schmälern zu wollen. dem Programm gefeilt, haben Filme gesucht, tage, dass wir viel davon in unsere eigene Ge - dabei gelacht und geweint, waren betroffen genwart und Zukunft mitnehmen können. Wir Wie entscheiden wir uns? Welche Kriterien und waren glücklich, haben Produzenten und legen wir an, im speziellen Fall als Kinomacher, Filmschaffende kontaktiert und haben dabei Fernsehredakteur, Förderer, Autor oder Regis - immer an Sie, an unser Publikum gedacht und seur, oder allgemein in dem Teil des Lebens, uns dabei gefragt, womit wir Sie anregen kön - den man gewählt hat oder an den man hinge - nen, wo wir Ihnen eine neue Ansicht zur Dis - kommen ist, in der Auswahl unseres Handelns. kussion stellen oder wo wir einfach nur Bilder Immer wieder sind es im künstlerischen Bereich zeigen können, die einen stumm und staunend die Fragen nach dem vermeintlichen Ge - zur Leinwand emporblicken lassen. Daraus ent - schmack der anderen und dem eigenen. Nach standen diese zehn Tage pures Kino, dieses 11. dem finanziellen Auskommen. Oder dem Zeit - Fünf Seen Filmfestival. geist. Und immer wieder daran anschließend das Suchen nach dem eigenen, wirklichen Wol - Dafür möchte ich mich zuerst bei meinen Mit - len, das man philosophisch oder psychologisch arbeiterInnen und ihrem unermüdlichen Ein - weitläufig hinterfragen könnte.