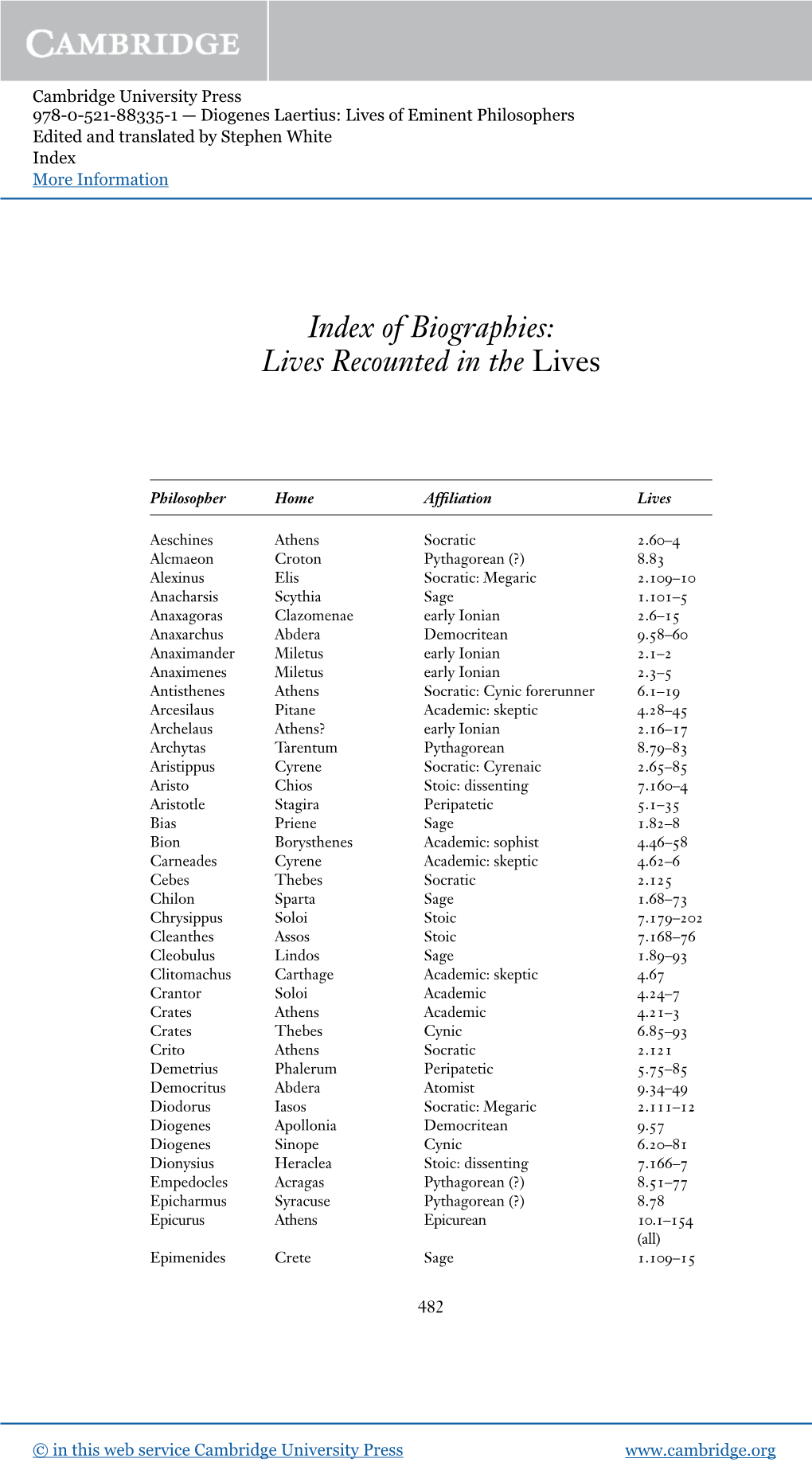

Index of Biographies: Lives Recounted in the Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics denote tables, maps, or illustrations Abdera 74 Cleomenes 237 ; coins 159, 276 , Abu Simbel 297 277, 279 ; food production 121, 268, Abydos 286 272 ; imports 268 ; Kleoitas 109 ; Achaea/Achaeans: Aigialos 213 ; Naucratis 269–271 ; pottery 191 ; basileus 128, 129, 134 ; Sparta 285 ; trade 268, 272 colonization 100, 104, 105, 107–108, Aegium 88, 91, 108 115, 121 ; democracy 204 ; Aelian 4, 186, 188 dialect 44 ; ethnos 91 ; Aeneas 109, 129 Herodotus 91 ; heroes 73, 108 ; Aeolians 45 , 96–97, 122, 292, 307 ; Homer 52, 172, 197, 215 ; dialect group 44, 45, 46 Ionians 50 ; migration 44, 45 , 50, Aeschines 86, 91, 313, 314–315 96 ; pottery 119 ; as province 68 ; Aeschylus: Persians 287, 308 ; Seven relocation 48 ; warrior tombs 49 Against Thebes 162 ; Suppliant Achilles 128, 129, 132, 137, 172, 181, Maidens 204 216 ; shield of 24, 73, 76, 138–139 Aetolia/Aetolians 20 ; dialect 299 ; Acrae 38 , 103, 110 Erxadieis 285 ; ethnos 91, 92 ; Acraephnium 279 poleis 93 ; pottery 50 ; West Acragas 38 , 47 ; democracy 204 ; Locris 20 foundation COPYRIGHTED 104, 197 ; Phalaris 144 ; Aëtos MATERIAL 62 Theron 149, 289 ; tyranny 150 Africanus, Sextus Julius 31 Adrastus 162 Agamemnon: Aeolians 97 ; anax 129 ; Aegimius 50, 51 Argos 182 ; armor 173 ; Aegina 3 ; Argos 3, 5 ; Athens 183, basileus 128, 129 ; scepter 133 ; 286, 287 ; captured 155 ; Schliemann 41 ; Thersites 206 A History of the Archaic Greek World: ca. 1200–479 BCE, Second Edition. Jonathan M. Hall. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, -

ARISTOXENUS of TARENTUM Rutgers University Studies in Classical Humanities

ARISTOXENUS OF TARENTUM Rutgers University Studies in Classical Humanities Series Editor: David C. Mirhady Advisory Board: William W. Fortenbaugh Dimitri Gutas Pamela M. Huby Timothy C. Powers Eckart Schütrumpf On Stoic and Peripatetic Ethics: The Work of Arius Didymus I Theophrastus of Eresus: On His Life and Work II Theophrastean Studies: On Natural Science, Physics and Metaphysics, Ethics, Religion and Rhetoric III Cicero’s Knowledge of the Peripatos IV 7KHRSKUDVWXV+LV3V\FKRORJLFDO'R[RJUDSKLFDODQG6FLHQWLÀF Writings V Peripatetic Rhetoric after Aristotle VI The Passionate Intellect: Essays on the Transformation of Classical Traditions presented to Professor I.G. Kidd VII Theophrastus: Reappraising the Sources VIII Demetrius of Phalerum: Text, Translation and Discussion IX Dicaearchus of Messana: Text, Translation and Discussion X Eudemus of Rhodes XI Lyco of Troas and Hieronymus of Rhodes XII Aristo of Ceos: Text, Translation and Discussion XIII Heraclides of Pontus: Text and Translation XIV Heraclides of Pontus: Discussion XV Strato of Lampsacus: Text, Translation and Discussion XVI ARISTO XENUS OF TARENTUM DISCUSSION RUTGERS UNIVERSITY STUDIES IN CLASSICAL HUMANITIES VOLUMEXVU EDITED BY eARL A. HUFFMAN First published 2012 by Transaction Publishers Published 2017 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 2012 by Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

The Roles of Solon in Plato's Dialogues

The Roles of Solon in Plato’s Dialogues Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Samuel Ortencio Flores, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Bruce Heiden, Advisor Anthony Kaldellis Richard Fletcher Greg Anderson Copyrighy by Samuel Ortencio Flores 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a study of Plato’s use and adaptation of an earlier model and tradition of wisdom based on the thought and legacy of the sixth-century archon, legislator, and poet Solon. Solon is cited and/or quoted thirty-four times in Plato’s dialogues, and alluded to many more times. My study shows that these references and allusions have deeper meaning when contextualized within the reception of Solon in the classical period. For Plato, Solon is a rhetorically powerful figure in advancing the relatively new practice of philosophy in Athens. While Solon himself did not adequately establish justice in the city, his legacy provided a model upon which Platonic philosophy could improve. Chapter One surveys the passing references to Solon in the dialogues as an introduction to my chapters on the dialogues in which Solon is a very prominent figure, Timaeus- Critias, Republic, and Laws. Chapter Two examines Critias’ use of his ancestor Solon to establish his own philosophic credentials. Chapter Three suggests that Socrates re- appropriates the aims and themes of Solon’s political poetry for Socratic philosophy. Chapter Four suggests that Solon provides a legislative model which Plato reconstructs in the Laws for the philosopher to supplant the role of legislator in Greek thought. -

Aristotle's Categories in the Early Roman Empire, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2015, in Sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr

Citation style Andrea Falcon: Rezension von: Michael J. Griffin: Aristotle's Categories in the Early Roman Empire, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2015, in sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr. 7 [15.07.2015], URL:http://www.sehepunkte.de/2015/07/27098.html First published: http://www.sehepunkte.de/2015/07/27098.html copyright This article may be downloaded and/or used within the private copying exemption. Any further use without permission of the rights owner shall be subject to legal licences (§§ 44a-63a UrhG / German Copyright Act). sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr. 7 Michael J. Griffin: Aristotle's Categories in the Early Roman Empire This is a book about the reception of Aristotle's Categories from the first century BC to the second century AD. The Categories does not appear to have circulated in the Hellenistic era. By contrast, this short but enigmatic treatise was at the center of the so-called return to Aristotle in the first century BC. The book under review tells us the story of this remarkable reversal of fortune. The main characters in this story are philosophers working in the three main philosophical traditions of post- Hellenistic philosophy. For the Peripatetic tradition, these are Andronicus of Rhodes and Boethus of Sidon. For the Academic and Platonic tradition, Eudorus of Alexandria and Lucius. For the Stoic tradition, Athenodorus and Cornutus. A supporting role is reserved to the following interpreters of the Categories : Aristo of Alexandria, Ps-Archytas, Nicostratus, Aspasius, Herminus, and Adrastus. In broad outline, the story told in the book goes as follows: Andronicus of Rhodes rescued the Categories from obscurity by deciding to place it at the beginning of his catalogue of Aristotle's writings (chapter 2). -

The Influence of Achaemenid Persia on Fourth-Century and Early Hellenistic Greek Tyranny

THE INFLUENCE OF ACHAEMENID PERSIA ON FOURTH-CENTURY AND EARLY HELLENISTIC GREEK TYRANNY Miles Lester-Pearson A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11826 This item is protected by original copyright The influence of Achaemenid Persia on fourth-century and early Hellenistic Greek tyranny Miles Lester-Pearson This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews Submitted February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Miles Lester-Pearson, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2015. Date: Signature of Candidate: 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Curriculum Vitae Voula Tsouna

1 Curriculum Vitae Voula Tsouna Department of Philosophy, University of California Santa Barbara, CA 93106-3090 [email protected] Place of Birth: Athens, Greece Nationality: Greek (EU) & USA Languages: Ancient Greek, Latin, French (fluent), English (fluent), Modern Greek (fluent), Italian (competent), German (reading) AREA OF SPECIALIZATION Ancient Philosophy AREAS OF COMPETENCE Siècle des Lumières (French Enlightment), Early Modern Philosophy, topics in Epistemology, Moral Psychology, and Ethics. EDUCATION 1988 PhD (Thèse de doctorat), Ancient Philosophy, University of Paris X 1984-86 Doctoral Research, fully enrolled graduate student at the University of Cambridge, King’s College 1984 Diplôme d’Études Approfondies (DEA, equivalent to the MA), Ancient Philosophy, University of Paris X 1983 Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy summa cum laude (Πτυχεῖον summa cum laude), Philosophy, University of Athens ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2006–present University of California at Santa Barbara, Full Professor 2000–2006 University of California at Santa Barbara, Associate Professor 1997–2000 University of California at Santa Barbara, Assistant Professor 1997 (Winter) University of California at Santa Barbara, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy 2010 (Spring) University of Crete, Holder of the Michelis Chair in Aesthetics at the Department of Philosophy and Social Studies 1994–1996 Pomona College, Visiting Assistant Professor 1992–1993 University of Glasgow, Scotland, Research Fellow 1991–1992 California State University at San Bernardino, Lecturer -

Aristotelianism in the First Century BC

CHAPTER 5 Aristotelianism in the First Century BC Andrea Falcon 1 A New Generation of Peripatetic Philosophers The division of the Peripatetic tradition into a Hellenistic and a post- Hellenistic period is not a modern invention. It is already accepted in antiquity. Aspasius speaks of an old and a new generation of Peripatetic philosophers. Among the philosophers who belong to the new generation, he singles out Andronicus of Rhodes and Boethus of Sidon.1 Strabo adopts a similar division. He too distinguishes between the older Peripatetics, who came immediately after Theophrastus, and their successors.2 He collectively describes the latter as better able to do philosophy in the manner of Aristotle (φιλοσοφεῖν καὶ ἀριστοτελίζειν). It remains unclear what Strabo means by doing philosophy in the manner of Aristotle.3 But he certainly thinks that the philosophers who belong to the new generation, and not those who belong to the old one, deserve the title of true Aristotelians. For Strabo, the event separating the old from the new Peripatos is the rediscovery and publication of Aristotle’s writings. We may want to resist Strabo’s negative characterization of the earlier Peripatetics. For Strabo, they were not able to engage in philosophy in any seri- ous way but were content to declaim general theses.4 This may be an unfair judgment, ultimately based on the anachronistic assumption that any serious philosophy requires engagement with an authoritative text.5 Still, the empha- sis that Strabo places on the rediscovery of Aristotle’s writings suggests that the latter were at the center of the critical engagement with Aristotle in the 1 Aspasius, On Aristotle’s Ethics 44.20–45.16. -

Plato Apology of Socrates and Crito

COLLEGE SERIES OF GREEK AUTHORS EDITED UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF JOHN WILLIAMS WHITE, LEWIS R. PACKARD, a n d THOMAS D. SEYMOUR. PLATO A p o l o g y o f S o c r a t e s AND C r i t o EDITED ON THE BASIS OF CRON’S EDITION BY LOUIS DYER A s s i s t a n t ·Ρι;Οχ'ε&^ο^ ι ν ^University. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY GINN & COMPANY. 1902. I P ■ C o p · 3 Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1885, by J o h n W il l ia m s W h i t e a n d T h o m a s D. S e y m o u r , In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. J . S. C u s h in g & Co., P r i n t e r s , B o s t o n . PREFACE. T his edition of the Apology of Socrates and the Crito is based upon Dr. Christian Cron’s eighth edition, Leipzig, 1882. The Notes and Introduction here given have in the main been con fined within the limits intelligently drawn by Dr. Cron, whose commentaries upon various dialogues of Plato have done and still do so much in Germany to make the study of our author more profitable as well as pleasanter. No scruple has been felt, how ever, in making changes. I trust there are few if any of these which Dr. Cron might not himself make if he were preparing his work for an English-thinking and English-speaking public. -

1 the Rhetorical Use of Torture in Attic Forensic Oratory VASILEIOS

The Rhetorical Use of Torture in Attic Forensic Oratory VASILEIOS ADAMIDIS Mailing Address: Flat 2, 43 Burns street, NG7 4DS Nottingham United Kingdom Email address: [email protected] Tel: +44(0)7930520275 1 The Rhetorical Use of Torture in Attic Forensic Oratory ABSTRACT: Come 'regola', la tortura di schiavi innocenti che è stata concordata dai querelantia fini probatori (βάσανος probatori) fu ritenuto dagli oratori lo strumento più efficace per giungere alla verità. Questo paper, con riferimento alla psicologia dell'antica Grecia, spiega perché la menzionata regola fu di cruciale importanza per la retorica. Gli oratori, sulla base della presunta attendibilità dell'istituzione dei βάσανος, furono in grado di sviluppare argomenti basati sulle sfide (πρόκλησις), che possono essere comprese al meglio alla luce della concezione greca, piuttosto che moderna, di razionalità ed azione umana. Di conseguenza, a dispetto dell'incertezza che circonda l'attualità della tortura a fini probatori nell'età degli oratori, l'importanza retorica dei πρόκλησις εἰς βάσανον è innegabile e va esaminata attentamente. KEYWORDS: Basanos (βάσανος), Greek psychology, human motivation, practical reasoning. *** The institution of torture is highly controversial; its morality is extremely dubious and its expediency is, at minimum, questionable. A particular form of torture that seems completely indefensible from a modern perspective is the torture (βάσανος) of innocent slaves for evidentiary purposes in Athenian law. This has been characterised as ‘wanton and purposeless barbarity’1, yet has been explained as a way classical Athenian citizens reinforced their dominant political status and ‘confirm[ed] their own social hierarchy and cohesion’2. The barbarity and putative irrationality of evidentiary βάσανος3, in addition to the lack of evidence proving the actuality of this practice, make its existence, at least in the period of the Attic orators, doubtful4. -

The Appeal to Easiness in Aristotle's Protrepticus

THE APPEAL TO EASINESS IN ARISTOTLE’S PROTREPTICUS Matthew D. Walker [Uncorrected draft. To be published in Ancient Philosophy 39 (2019). Please cite only the final published version.] Aristotle’s Protrepticus sought to exhort its audience to engage in philosophy (filosofi&a), i.e., the “acquisition and use of wisdom” (kth~si&v te kai_ xrh~siv sofi&av: 6, 40.2-3/B53; cf. 6, 37.7-9/B8).1 The Protrepticus is now lost. But work by D.S. Hutchinson and Monte Ransome Johnson (2005) has confirmed earlier speculation – initiated by Ingram Bywater (1869) – that Iamblichus preserves large passages of the work in his own Protrepticus. Hutchinson and Johnson 2018 argue that significant portions of the Protrepticus also appear in Iamblichus’ De Communi Mathematica Scientia (DCMS), and that the Protrepticus was originally a dialogue. In passages preserved in Chapter 6 of Iamblichus’ Protrepticus (at 40.15-41.2/B55- 56), Aristotle offers three linked arguments for the claim that philosophy is easy. (I number the arguments in the translation that follows.) [1] For, with no pay coming from people to those who philosophize, on account of which [the latter] would have labored strenuously in this way, and with a great lead extended to the other arts, nevertheless their passing [the other arts] in exactness despite running a short time seems to me to be a sign of the easiness about philosophy. [2] And further, everybody’s feeling at home in it and wishing to occupy leisure with it, leaving aside all else, is no small sign that the close attention comes with pleasure; for no one is willing to labor for a long time. -

Macedonische Koningen in Beeld De Representatie Van De Macedonische Koningen Amyntas III, Philippus II, Alexander III En Demetrios I in Kunst, Architectuur En Munten

Macedonische Koningen in Beeld De representatie van de Macedonische koningen Amyntas III, Philippus II, Alexander III en Demetrios I in kunst, architectuur en munten Student: Marinde Hiemstra Studentnummer: 3666581 Docent: F. van den Eijnde Cursus: Onderzoeksseminar III Universiteit Utrecht Maart 2013 Inhoudsopgave Inleiding......................................................................................................................................2 Amyntas III.................................................................................................................................5 Philippus II.................................................................................................................................8 Alexander III 'de Grote'............................................................................................................12 Demetrios I 'Poliorketes'...........................................................................................................16 Conclusie..................................................................................................................................20 Literatuurlijst............................................................................................................................23 1 Art and architecture are mirrors of a society. They reflect the state of its values, especially in times of crisis or transition. ~ P. Zanker1. Inleiding In 338 voor Christus gaf Philippus II van Macedonië opdracht om een rond gebouw neer te zetten naast de -

Historical Synopsis of the Aristotelian Commentary Tradition (In Less Than Sixty Minutes)

HISTORICAL SYNOPSIS OF THE ARISTOTELIAN COMMENTARY TRADITION (IN LESS THAN SIXTY MINUTES) Fred D. Miller, Jr. CHAPTER 1 PERIPATETIC SCHOLARS Aristotle of Stagira (384–322 BCE) Exoteric works: Protrepticus, On Philosophy, Eudemus, etc. Esoteric works: Categories, Physics, De Caelo, Metaphysics, De Anima, etc. The legend of Aristotle’s misappropriated works Andronicus of Rhodes: first edition of Aristotle’s works (40 BCE) Early Peripatetic commentators Boethus of Sidon (c. 75—c. 10 BCE) comm. on Categories Alexander of Aegae (1st century CE)comm. on Categories and De Caelo Adrastus of Aphrodisias (early 1st century) comm. on Categories Aspasius (c. 131) comm. on Nicomachean Ethics Emperor Marcus Aurelius establishes four chairs of philosophy in Athens: Platonic, Peripatetic, Stoic, Epicurean (c. 170) Alexander of Aphrodisias (late 2nd —early 3rd century) Extant commentaries on Prior Analytics, De Sensu, etc. Lost comm. on Physics, De Caelo, etc. Exemplar for all subsequent commentators. Comm. on Aristotle’s Metaphysics Only books 1—5 of Alexander’s comm. are genuine; books 6—14 are by ps.-Alexander . whodunit? Themistius (c. 317—c. 388) Paraphrases of Physics, De Anima, etc. Paraphrase of Metaphysics Λ (Hebrew translation) Last of the Peripatetics CHAPTER 2 NEOPLATONIC SCHOLARS Origins of Neoplatonism Ammonius Saccas (c. 175—242) forefather of Neoplatonism Plotinus (c. 205—260) the Enneads Reality explained in terms of hypostases: THE ONE—> THE INTELLECT—>WORLD SOUL—>PERCEPTIBLE WORLD Porphyry of Tyre (232–309) Life of Plotinus On the School of Plato and Aristotle Being One On the Difference Between Plato and Aristotle Isagoge (Introduction to Aristotle’s Categories) What is Neoplatonism? A broad intellectual movement based on the philosophy of Plotinus that sought to incorporate and reconcile the doctrines of Plato, Pythagoras, and Aristotle with each other and with the universal beliefs and practices of popular religion (e.g.