This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

The Spirit of the Page: Books and Readers at the Abbey of Fécamp, C

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/32272 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Weston, Jennifer Ann Title: The Spirit of the Page: Books and Readers at the Abbey of Fécamp, c. 1000-1200 Issue Date: 2015-03-10 Chapter 5 Books for Selective Reading at Fécamp The presence of navigational reading aids in eighteen manuscripts from the Fécamp corpus are suggestive of a reader who needed to locate specific chapters of the book, and, therefore, indicate a mode of reading that was different from the comprehensive approach of lectio divina. The present chapter aims to find an appropriate context of use for these navigational reading aids in the Benedictine monastery. Over the course of this chapter, I examine three book-types from the Fécamp corpus that contain reading aids: Giant Bibles, Gospel Books, and patristic texts. Moreover, I identify three settings where these books (equipped with navigation) would have been used: during the celebration of the liturgy (the Mass and Divine Office), during meal-time reading in the refectory, and during the evening gathering of Collation. Indeed, just as the Fécamp scribes designed many of their books to suit the practice of lectio divina (as shown in Part One of this study), it seems that they also custom-designed some of their books to accommodate a second mode of devotional reading. ! ! 1. Bibles with Navigation There are two Giant Bibles from the Fécamp corpus that include navigational reading aids: Rouen 1 and Rouen 7. As noted in the previous chapter, both books are presented in a large format and each contain a large collection of books from the Old and New Testament: Rouen 1 contains all but the Gospels, and Rouen 7 contains the Old Testament and the Gospels.1 The presence of navigational reading aids in these two Bibles (in the form of chapter tables and running titles) suggest that both of these volumes were designed to support searching and finding throughout the volume. -

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

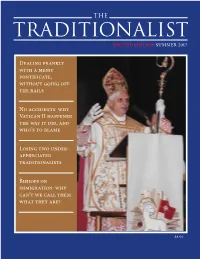

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

What Is the Roman Missal?

Roman Missal Bulletin Insert Series #1 WHAT IS THE ROMAN MISSAL? Book of the Gospels (Evangeliary) for the scripture readings, and additional books for the chants and antiphons. Slight changes and additions developed as manuscripts were handed on and hand scribed. Eventually the chants, scripture readings, prayer texts, and instructions were compiled into a single volume, the Missale Plenum (complete Missal). When Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable printing press in 1470, this allowed the Mass texts to become standardized and published universally. In 1474, the first Missale Romanum (Roman Missal) was printed in Latin and the texts contained in this volume evolved over the five ensuing centuries. Because the amount of scripture proclaimed at Mass increased following the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), the Missal was divided into two separate books so that its size would not be overwhelming. The Sacramentary contained the instructions (rubrics), the prayers (the Gloria, the Creed, the Eucharistic Prayer, the Our Father, etc.), Over the past several months, you may have and the chants and dialogues (the entrance heard a lot about the revised translation of antiphons, The Lord be with you, etc.). The The Roman Missal. Some may be wondering, Lectionary contained the readings for ―What is The Roman MissaI and how does Sundays, Feast Days and weekdays. It is this new translation affect me?‖ the former of these books, the Sacramentary First of all, it is important to note that the that has been retranslated. With this structure of the Mass is not changing. The translation, the name of the book will change Biblical readings will not change either, but from The Sacramentary to The Roman some of the prayers we say (and sing) and Missal, a translation of the Latin title, the prayers the priest says will be changed Missale Romanum. -

I. a Humanist John Merbecke

Durham E-Theses Renaissance humanism and John Merbecke's - The booke of Common praier noted (1550) Kim, Hyun-Ah How to cite: Kim, Hyun-Ah (2005) Renaissance humanism and John Merbecke's - The booke of Common praier noted (1550), Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2767/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Renaissance Humanism and John Merbecke's The booke of Common praier noted (1550) Hyun-Ah Kim A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Durham University Department of Music Durham University .2005 m 2001 ABSTRACT Hyun-Ah Kim Renaissance Humanism and John Merbecke's The booke of Common praier noted (1550) Renaissance humanism was an intellectual technique which contributed most to the origin and development of the Reformation. -

ABOUT the Middle of the Thirteenth Century the Dean and Chapter of St

XIII.—Visitations of certain Churches in the City of London in the patronage of St. Paul's Cathedral Church, between the years 1138 and 1250. By W. SPARROW SIMPSON, D.D., Sub-Dean and Librarian of St. Paul's. Read January 16, 1896. ABOUT the middle of the thirteenth century the Dean and Chapter of St. Paul's Cathedral Church made a minute and careful visitation of churches in their gift, lying in the counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, and Middlesex. The text of that visitation has been lately printed in a volume issued by the Camden Society.'1 The record of their proceedings is so copious that a clear and distinct account can be given of the ornaments, vestments, books, and plate belonging to these churches; and some insight can be gained into the relations which existed between the parishioners, the patrons, and the parish priest. The visitations now for the first time printed are not so full and ample as could be desired. But so little authentic information is to be gathered about the furniture and ornaments of churches in the city of London at this very early period, that even these brief records may be acceptable to antiquaries. The manuscript from which these inventories have been transcribed is one of very high importance. Mr. Maxwell Lyte describes it as " a fine volume, of which the earlier part was written in the middle of the twelfth century," and he devotes about eighteen columns of closely-printed matter to a calendar of its contents illustrated by very numerous extracts." The book is known as Liber L, and the most important portions of it are now in print. -

Liturgical Press Style Guide

STYLE GUIDE LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org STYLE GUIDE Seventh Edition Prepared by the Editorial and Production Staff of Liturgical Press LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover design by Ann Blattner © 1980, 1983, 1990, 1997, 2001, 2004, 2008 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. Printed in the United States of America. Contents Introduction 5 To the Author 5 Statement of Aims 5 1. Submitting a Manuscript 7 2. Formatting an Accepted Manuscript 8 3. Style 9 Quotations 10 Bibliography and Notes 11 Capitalization 14 Pronouns 22 Titles in English 22 Foreign-language Titles 22 Titles of Persons 24 Titles of Places and Structures 24 Citing Scripture References 25 Citing the Rule of Benedict 26 Citing Vatican Documents 27 Using Catechetical Material 27 Citing Papal, Curial, Conciliar, and Episcopal Documents 27 Citing the Summa Theologiae 28 Numbers 28 Plurals and Possessives 28 Bias-free Language 28 4. Process of Publication 30 Copyediting and Designing 30 Typesetting and Proofreading 30 Marketing and Advertising 33 3 5. Parts of the Work: Author Responsibilities 33 Front Matter 33 In the Text 35 Back Matter 36 Summary of Author Responsibilities 36 6. Notes for Translators 37 Additions to the Text 37 Rearrangement of the Text 37 Restoring Bibliographical References 37 Sample Permission Letter 38 Sample Release Form 39 4 Introduction To the Author Thank you for choosing Liturgical Press as the possible publisher of your manuscript. -

Papal Tiara Commissioned and Gifted to Benedict XVI by SHAWN TRIBE

WRITERS SEARCH NLM ARCHIVES Shawn Tribe Founder & Editor Search NLM Email, Twitter Pilgrimage in Tuscany NLM Quiz: Can You Guess What This Is? And the by Shawn Tribe Answer is.... by Shawn Tribe Gregor Kollmorgen We have given a great deal of coverage to the Chartres FOLLOW NLM Pilgrimage, but another pilgrimage in Europe ... Well it seems like it's about that time again; the NLM General quiz. (See our previous quizzes: Quiz 1 and o... Email A New Entry in the Rupture and Continuity Debate: Enrico Maria Radaelli Video from the Recessional, Chartres Cathedral by Shawn Tribe by Shawn Tribe Matthew Alderman Another Italian has entered into a debate which we've ... Sacred Architecture been reporting on by way of Chiesa; namely the... How the Artistic Liturgical Traditions Email Current Status of the Dominican Rite: A Complement Each Other Summary by David Clayton Gregory DiPippo by Fr. Augustine Thompson, O.P. Here is a passage taken from the Office of Readings, Rome Correspondent Readers often ask about where they can attend Saturday, 6th week of Eastertide. It is part of... celebrations of the Dominican Rite Mass and what its c... Email Fra’ Fredrik Crichton-Stuart, R.I.P. Tucker on Magister by Shawn Tribe by Shawn Tribe H.E. Fra’ Fredrik Crichton-Stuart, Grand Prior of David Clayton A couple of weeks ago, we made brief reference to a England, 1940 – 2011Edinburgh, 14 June 2011Fra' Fr... Sacred Art rather critical and needless to say controversia... Sant'Angelo in Formis, Capua, Italy Email, Twitter Solemn Evensong & Benediction in Oxford by Shawn Tribe by Br Lawrence Lew, O.P. -

Saint Pius V Altar Server Dictionary Promulgated During the Pontificate of Francis, 266Th Successor to the Apostle Peter

1 Saint Pius V Altar Server Dictionary Promulgated during the Pontificate of Francis, 266th successor to the Apostle Peter. 1. The main areas of the church with which you should be concerned: 1. The sanctuary is the area in the center and toward the front of the church where the altar, the ambo, and the priest’s and altar server’s chairs are located. 2. The sacristy is the room where the priest, deacon and altar servers vest and prepare for Mass. Many of the items used in the celebration of the Mass are stored there. 3. Other areas include the baptistry, where the baptismal font is located and where baptisms may be celebrated; the vestibule, the entrance to our church; and our four confessionals, where the sacrament of penance is celebrated. 2. Books used at Holy Mass: 1. The Lectionary is the large book containing the Bible readings. There may be a separate Book of the Gospels, called the evangeliary. 2. The Roman Missal is the large book used by the priest when standing at his chair and at the altar during Mass. 3. Other books may be used too in the sanctuary, including a hymnal, a binder containing general intercessions, ritual books for the various sacraments, and a binder of announcements. Our binders are different colors, matching the liturgical color of the day/season. 3. Vessels used at Holy Mass: 1. The chalice is the cup that holds the wine for consecration and communion. 2. The paten is a plate that holds the hosts for consecration and communion. -

The General Instruction of the Roman Missal Introduction

THE GENERAL INSTRUCTION OF THE ROmAN mISSAL INTRODUCTION 1. As christ the Lord was about to celebrate with the disciples the paschal supper in which he insti- tuted the Sacrifice of hisb ody and blood, he commanded that a large, furnished upper room be prepared (Lk 22:12). indeed, the church has always judged that this command also applied to herself whenever she decided about things related to the disposition of people’s minds, and of places, rites and texts for the celebration of the Most holy eucharist. the present norms, too, prescribed in keeping with the will of the Second vatican council, together with the new Missal with which the church of the roman rite will henceforth celebrate the Mass, are again a demonstration of this same solicitude of the church, of her faith and her unaltered love for the supreme mystery of the eucharist, and also attest to her continu- ous and consistent tradition, even though certain new elements have been introduced. Testimony of an Unaltered Faith 2. The sacrificial nature of the Mass, solemnly defended by thec ouncil of trent, because it accords with the universal tradition of the church,1 was once more stated by the Second vatican council, which pronounced these clear words about the Mass: “at the Last Supper, our Savior instituted the eucharistic Sacrifice of his body and blood, by which the Sacrifice of his cross is perpetuated until he comes again; and till then he entrusts the memorial of his Death and resurrection to his beloved spouse, the church.”2 What is taught in this way by the council is consistently expressed in the formulas of the Mass. -

THE DISSEMINATION and RECEPTION of the ORDINES ROMANI in the CAROLINGIAN CHURCH, C.750-900

THE DISSEMINATION AND RECEPTION OF THE ORDINES ROMANI IN THE CAROLINGIAN CHURCH, c.750-900 Arthur Robert Westwell Queens’ College 09/2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 Arthur Robert Westwell Thesis Summary: The Dissemination and Reception of the Ordines Romani in the Carolingian Church, c.750- 900. The ordines romani are products of a ninth-century attempt to correct liturgy across Europe. Hitherto, scholarship has almost exclusively focused on them as sources for the practices of the city of Rome, narrowly defined, disregarding how they were received creatively and reinterpreted in a set of fascinating manuscripts which do not easily fit into traditional categories. This thesis re- envisages these special texts as valuable testimonies of intent and principle. In the past few decades of scholarship, it has been made very clear that what occurred under the Carolingians in the liturgy did not involve the imposition of the Roman rite from above. What was ‘Roman’ and ‘correct’ was decided by individuals, each in their own case, and they created and edited texts for what they needed. These individuals were part of intensive networks of exchange, and, broadly, they agreed on what they were attempting to accomplish. Nevertheless, depending on their own formation, and the atmosphere of their diocese, the same ritual content could be interpreted in numerous different ways. Ultimately, this thesis aims to demonstrate the usefulness of applying new techniques of assessing liturgical manuscripts, as total witnesses whose texts interpret each other, to the ninth century. Each of the ordo romanus manuscripts of the ninth century preserves a fascinating glimpse into the process of working out what ‘correct’ liturgy looked like, by people intensely invested in that proposition. -

PRO PERFIDIS JUDAEIS JOHN M. OESTERREICHER Mankattanville College of the Sacred Heart

PRO PERFIDIS JUDAEIS JOHN M. OESTERREICHER Mankattanville College of the Sacred Heart f\N GOOD Friday, the Church solemnly intercedes for all within and ^ without her fold. Among her petitions is one for the Jewish people. Oremus et pro perfidis Judaeis: ut Deus et Dominus noster auf erat velamen de cordibus eorum; ut et ipsi agnoscant Jesum Christum Dominum nostrum. Non respondetur Amen, nee dicitur Oremus, aut Flectamus genua, aut Levate, sed statim dicitur: Omnipotens sempiterne Deus, qui etiam Judaicam perfidìam a tua misericordia non repellis: exaudí preces nostras, quas pro illiuspopuli obcaecatione deferimus; ut, agnita veritatis tuae luce, quae Christus est, a suis tenebris eruantur. Per eumdem Dominum. Amen. This is the text given in the Roman Missal. Two problems arise in regard to this prayer: the meaning of perfidia and perfidus, and the significance of the rubric directing certain omissions. THE MEANING OF "PERFIDIA" The St. Andrew Missal in its 1927 edition reads: "Let us pray for the perfidious Jews"; in the edition of 1943, this is changed to: "Let us pray for the faithless Jews." Father Lasance's Missal of 1935 speaks of the "unfaithful Jews" and of "Jewish faithlessness." The Missal of Fathers Callan and McHugh gives in all editions the render ing "perfidious Jews." Father Stedman's Lenten Missal {1941) translates: "Let us pray for the unbelieving Jews." It is our contention that perfidus denotes neither "perfidious" nor "faithless" nor "unfaithful" in their present connotations, but "un believing" or "disbelieving." The liturgy does not pass moral judg ments, nor would it label the Jews "treacherous" or "wicked." In saying perfidia judaica, the Church mourns Israel's disbelief in Christ, holding that from Abraham's children, least of all, would one expect Isuch refusal of faith.