PRO PERFIDIS JUDAEIS JOHN M. OESTERREICHER Mankattanville College of the Sacred Heart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

York Minster's Chapter House and Its Painted Glass Narratives

York Minster’s Chapter House and its Painted Glass Narratives Volume 1 of 3 Ann Hilary Moxon PhD University of York History of Art December 2017 Abstract This thesis focuses on the late thirteenth-century narrative glazing scheme of the chapter house in York Minster and the political and religious context of its design. Created as an intrinsic and integrated part of one of the most elaborate and important buildings in the period, the glass has suffered interventions affecting both its appearance and the positions of its narrative panels. By examining the glass in the context of contemporary visual and textual material, it has been possible to reconstruct the original order of the panels and to identify the selection of episodes the lives of the saints, some for the first time. The study has demonstrated the extent to which the iconography was rooted in liturgy and theology relevant to the period which, in turn, reflected the priorities of a dominant group among the active members of Chapter for whose use the building was constructed and, by extension, the contemporary Church. Further, the glass shows strong Mariological themes which reflected features in the rest of the decorative scheme and the architecture of the chapter house, indicating that the glazing scheme may have been conceived as part of the architectural whole. The conclusions are supported by parallel research into the prosopography of the contemporary Chapter which additionally suggests that the conception of the programme may have had its roots in the baronial wars of the -

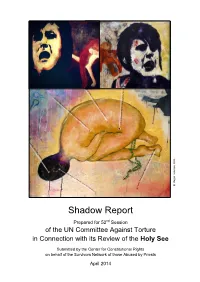

Shadow Report

, 2013 © Megan Peterson Shadow Report Prepared for 52nd Session of the UN Committee Against Torture in Connection with its Review of the Holy See Submitted by the Center for Constitutional Rights on behalf of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests April 2014 Cover Art Copyright Megan Peterson, 2013. All rights reserved. Megan Peterson is an artist and survivor of sexual violence by a priest. She is also a complainant in the effort to hold Vatican officials accountable for rape and sexual violence as crimes against humanity in the International Criminal Court and a member of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. Table of Contents Submitting Organizations iii List of Key Commissions, Inquiries and Investigations iv-v Introduction 1 I. The Committee Has Long Recognized Rape and Sexual Violence as Forms of Torture and Cruel, Inhuman, and Degrading Treatment and Punishment 4 II. Numerous Commissions and Inquiries Around the World Have Established the Existence of Widespread Rape and Sexual Violence in the Church 6 III. Rape and Sexual Violence Have Resulted in Severe Pain and Suffering, Both Physical and Mental, and Have Amounted to Torture and Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment 8 A. Suicides 10 B. Lasting Physical, Mental, Psychological and Emotional Harm 11 IV. The Holy See’s Policies and Practices Have Enabled, and Continue to Enable, the Widespread Rape and Sexual Violence and Result in Severe Physical and Mental Harm 13 A. Legal Status of the Holy See and Implications for Fulfillment of its Obligations under the Convention 13 B. Structure of the Church and Chain of Command 14 C. -

The Church in a Change of Era Massimo Faggioli

The Church in a Change of Era How the Franciscan reforms are changing the Catholic Church Massimo Faggioli Copyright © 2019 Massimo Faggioli All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher. @international.la-croix.com is a site of La Croix Network Visit https://international.la-croix.com/ FOREWORD We live in an age of immediate communication and instant responses. One of the corrosive effects of such an “immediate” world is the loss of a sense of history. That sense has nothing to do with the sense of nostalgia for better times in the past – in the Church and across societies. It is the sad outcome of a failure in many education systems around the world to properly value the study of history. Massimo Faggioli is one significant remedy to that deficiency as far as the Catholic Church is concerned. Catholic History and Law A helpful comparison is found by comparing the Church and its evolution to the establishment and growth of the rule of law because a thorough grasp of history is important to understanding good legal practice and the value and the circumstances within which a statute is created by legislatures and courts. As any lawyer worth talking to will tell you, laws are created to remedy an abuse. What is the abuse? All offences are against a deeply held value. A crime is an abuse of a value. -

Interactions Between Medieval Clergy and Laity in a Regional Context

Clergy and Commoners: Interactions between medieval clergy and laity in a regional context Andrew W. Taubman Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of York Centre for Medieval Studies 2009 Taubman 2 Abstract This thesis examines the interactions between medieval clergy and laity, which were complex, and its findings trouble dominant models for understanding the relationships between official and popular religions. In the context of an examination of these interactions in the Humber Region Lowlands during the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, this thesis illustrates the roles that laity had in the construction of official and popular cultures of medieval religion. Laity and clergy often interacted with each other and each other‟s culture, with the result that both groups contributed to the construction of medieval cultures of religion. After considering general trends through an examination of pastoral texts and devotional practices, the thesis moves on to case studies of interactions at local levels as recorded in ecclesiastical administrative documents, most notably bishops‟ registers. The discussion here, among other things, includes the interactions and negotiations surrounding hermits and anchorites, the complaints of the laity, and lay roles in constructing the religious identity of nuns. The Conclusion briefly examines the implications of the complex relationships between clergy and laity highlighted in this thesis. It questions divisions between cultures of official and popular religion and ends with a short case study illustrating how clergy and laity had the potential to shape the practices and structures of both official and popular medieval religion. Taubman 3 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... -

THE PATER NOSTER and the LAITY in ENGLAND C.700

THE PATER NOSTER AND THE LAITY IN ENGLAND c.700 - 1560 WITH SPECIAL FOCUS ON THE CLERGY’S USE OF THE PRAYER TO STRUCTURE BASIC CATECHETICAL TEACHING ANNA EDITH GOTTSCHALL A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SCHOOL OF ENGLISH, DRAMA AND AMERICAN AND CANADIAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM NOVEMBER 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. At present no scholar has provided an in-depth study into the dissemination of the Pater Noster outside the clerical sphere. This thesis provides a detailed consideration of the ways in which the Pater Noster was taught to the laity in medieval England. It explores the central position of the prayer in the lay curriculum, the constitutions which played a fundamental role in its teaching, and the methods by which it was disseminated. Clerical expositions of the prayer and its tabular and diagrammatic representations are examined to consider the material available to assist the clergy in their pedagogical role. The ways in which material associated with the Pater Noster was modified and delivered to a lay audience provides an important component in the holistic approach of this thesis. -

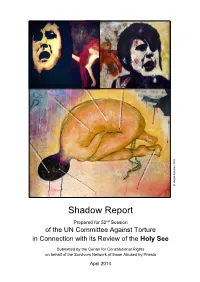

Shadow Report

© Megan Peterson, 2013 Peterson, © Megan Shadow Report Prepared for 52nd Session of the UN Committee Against Torture in Connection with its Review of the Holy See Submitted by the Center for Constitutional Rights on behalf of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests April 2014 Cover Art Copyright Megan Peterson, 2013. All rights reserved. Megan Peterson is an artist and survivor of sexual violence by a priest. She is also a complainant in the effort to hold Vatican officials accountable for rape and sexual violence as crimes against humanity in the International Criminal Court and a member of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. Table of Contents Submitting Organizations iii List of Key Commissions, Inquiries and Investigations iv-v Introduction 1 I. The Committee Has Long Recognized Rape and Sexual Violence as Forms of Torture and Cruel, Inhuman, and Degrading Treatment and Punishment 4 II. Numerous Commissions and Inquiries Around the World Have Established the Existence of Widespread Rape and Sexual Violence in the Church 6 III. Rape and Sexual Violence Have Resulted in Severe Pain and Suffering, Both Physical and Mental, and Have Amounted to Torture and Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment 8 A. Suicides 10 B. Lasting Physical, Mental, Psychological and Emotional Harm 11 IV. The Holy See’s Policies and Practices Have Enabled, and Continue to Enable, the Widespread Rape and Sexual Violence and Result in Severe Physical and Mental Harm 13 A. Legal Status of the Holy See and Implications for Fulfillment of its Obligations under the Convention 13 B. Structure of the Church and Chain of Command 14 C. -

Violence and Disorder in the Sede Vacante of Early Modern Rome, 1559-1655

VIOLENCE AND DISORDER IN THE SEDE VACANTE OF EARLY MODERN ROME, 1559-1655 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By John M. Hunt, M. A. ***** The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee Professor Robert C. Davis Professor Noel G. Parker ______________________________ Professor Barbara A. Hanawalt Advisor History Graduate Program Professor Terri Hessler ABSTRACT From the death of every pope until the election of his successor in the early modern era, the entire bureaucratic and judicial apparatus of the state in Rome and the Papal States effectively ceased to function. During this interregnum, known as the sede vacante (literally, “the vacant see”), violence and disorder dramatically increased as the papal government temporarily lost its control over the populace and its monopoly of violence. The College of Cardinals and local civic governments throughout the Papal States, authorities deputized to regulate affairs during sede vacante, failed to quell the upsurge of violence that commenced immediately upon the pope’s death. Contemporary observers and modern scholars have labeled the violence of sede vacante as meaningless and irrational. I argue, rather, that this period of unrest gave Romans and subjects of the Papal States an opportunity to perform actions increasingly forbidden by the centralizing papal government—and thus ultimately to limit the power of the government and prevent the development of the papacy into an absolute monarchy. Acting as individuals or as collectivities, Romans and papal subjects sought revenge against old enemies, attacked hated outsiders, criticized papal policies, and commented on the papal election. -

The Use of York: Characteristics of the Medieval Liturgical Office in York By

BORTHWICK INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF YORK The Use of York: Characteristics of the Medieval Liturgical Office in York by Matthew Cheung Salisbury Worcester College Oxford University BORTHWICK PAPER NO. 113 First Published 2008 © Matthew Cheung Salisbury ISSN: 0524-0913 ISBN-13: 978-1-904497-25-7 Acknowledgements I am particularly grateful for the advice of Dr Cristina Dondi and Professor Richard Sharpe. The Arundel Antiphonal appears by permission of Lady Herries of Terregles and the Trustees of the Arundel Castle Archives. I am grateful to the several libraries and archives that made their manuscript collections available, and wish particularly to thank for their assistance Dr Dorothy Johnston of the University of Nottingham; Dr John Robinson and Mrs Sara Rodger of Arundel Castle; and Mr Peter Young, Archivist of York Minster. In Oxford, Duke Humfrey was an ideal base of operations, and I thank the staff for their help. Finally, I thank Professor Nigel Morgan for generously allowing me to consult unpublished material and for supplying helpful advice. The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Trinity College, Toronto, and the Edward Kylie Trust are to be thanked for their generous financial support. Professor Andrew Hughes, among his manifold kindnesses, provoked an enduring need to explore ‘general impressions’, and made preoccupation with such explorations acceptable. St Everild’s Day, 2008. Abbreviations Manuscripts to which frequent references are made Full details of all manuscripts are in the first part of the Bibliography. Arundel Arundel Castle Archives York Antiphonal (s.n.) BLAdd.30511 London, British Library ms Additional 30511 BLAdd.34190 “ mss Additional 34190 & Egerton 2025 BLAdd.38624 “ ms Additional 38624 Burney.335 “ ms Burney 335 CAdd.2602 Cambridge, University Library ms Additional 2602 CAdd.3110 “ ms Additional 3110 Cosin Durham, University Library ms Cosin V.I.2 Gough.lit.1 Oxford, Bodleian Library ms Gough liturg. -

Fœderatio Internationalis Una Voce Positio N. 9

Fœderatio Internationalis Una Voce Positio N. 9 SILENCE AND INAUDIBILITY IN THE EXTRAORDINARY FORM JULY 2012 From the General Introduction These papers, commissioned by the International Federation Una Voce , are offered to stimulate and inform debate about the 1962 Missal among Catholics ‘attached to the ancient Latin liturgical tradition’, and others interested in the liturgical renewal of the Church. They are not to be taken to imply personal or moral criticism of those today or in the past who have adopted practices or advocated reforms which are subjected to criticism. In composing these papers we adopt the working assumption that our fellow Catholics act in good will, but that nevertheless a vigorous and well-informed debate is absolutely necessary if those who act in good will are to do so in light of a proper understanding of the issues. The authors of the papers are not named, as the papers are not the product of any one person, and also because we prefer them to be judged on the basis of their content, not their authorship. The International Federation Una Voce humbly submits the opinions contained in these papers to the judgement of the Church. Silence and Inaudibility in the Extraordinary Form: Abstract Liturgical texts read silently or inaudibly are a striking feature of the Extraordinary Form, and this has seemed scandalous to those attached to a didactic model of the liturgy, such as the supporters of the Synod of Pistoia. The explanation of why some texts cannot be heard by the Faithful is threefold. First, some texts are obscured by singing, at sung Masses; these include the texts actually being sung. -

Interpreting a Medieval Church Through Liturgy DH Frost

Interpreting a medieval church through liturgy DH Frost Can a medieval church ‑ which has fallen into ruin, been taken down stone by stone, and moved to another place – ever be brought to life again? Or, to put it another way, ‘Can these dry bones live?’ 1 Of course, in some ways they can never be what they were. The bishop will not make his regular visitations, to confirm his flock; the priest will not sit down in Lent to absolve the sins of all who live nearby; the pilgrims will not cross the river here, rosaries in hand; the daily round of Mass and Office, the circle of the Church’s Year, will rarely be kept; the Blessed Sacrament will not return to the hanging pyx above the high altar from which it was removed almost five hundred years ago. The dove is in a cage, now; it is on show. Yet every building in this museum faces a similar dilemma to some extent, and many resolve it with some degree of success. The farmers do not return every day from the fields to the farmhouses ‑ but we do see stooks across the fence from time to time. Pigs appear only occasionally in their sty – but sometimes they are there. In the schoolhouse, there is no resident schoolmaster ‑ but plenty of schoolchildren visit and learn things there. You can still buy bread from the Popty. Similarly, St Teilo’s already speaks volumes. Even if we keep silence, ‘the very stones will cry out’.2 It can have life as a place of awe and wonder ‑ even of prayer and devotion ‑ without any words of ours. -

Religion & Theology | Subject Catalog (PDF)

Religion & Theology Catalog of Microform (Research Collections, Serials, and Dissertations) www.proquest.com/en-US/catalogs/collections/rc-search.shtml [email protected] 800.521.0600 ext. 2793 or 734.761.4700 ext. 2793 USC018 -04 updated May 2010 Table of Contents About This Catalog ............................................................................................... 2 The Advantages of Microform ........................................................................... 3 Research Collections............................................................................................. 4 Manuscripts & Sacred Texts ............................................................................................................................5 Mission Collections ......................................................................................................................................... 17 Christianity ....................................................................................................................................................... 26 General Interest ............................................................................................................................................................ 26 Adventist ....................................................................................................................................................................... 32 Baptist ...........................................................................................................................................................................