Behavioraldespairinthetalmud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D. Stuhlman BHL, BA, MS LS, MHL In support of the Doctor of Hebrew Literature degree Jewish University of America Skokie, IL 2004 Page 1 Abstract Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs By Daniel D. Stuhlman, BA, BHL, MS LS, MHL Because of the differences in alphabets, entering Hebrew names and words in English works has always been a challenge. The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) is the source for many names both in American, Jewish and European society. This work examines given names, starting with theophoric names in the Bible, then continues with other names from the Bible and contemporary sources. The list of theophoric names is comprehensive. The other names are chosen from library catalogs and the personal records of the author. Hebrew names present challenges because of the variety of pronunciations. The same name is transliterated differently for a writer in Yiddish and Hebrew, but Yiddish names are not covered in this document. Family names are included only as they relate to the study of given names. One chapter deals with why Jacob and Joseph start with “J.” Transliteration tables from many sources are included for comparison purposes. Because parents may give any name they desire, there can be no absolute rules for using Hebrew names in English (or Latin character) library catalogs. When the cataloger can not find the Latin letter version of a name that the author prefers, the cataloger uses the rules for systematic Romanization. Through the use of rules and the understanding of the history of orthography, a library research can find the materials needed. -

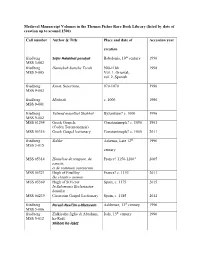

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (Listed by Date of Creation up to Around 1500) Call Number Au

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (listed by date of creation up to around 1500) Call number Author & Title Place and date of Accession year creation friedberg Sefer Halakhot pesuḳot Babylonia, 10 th century 1996 MSS 3-002 friedberg Ḥamishah ḥumshe Torah 900-1188 1998 MSS 9-005 Vol. 1, Oriental; vol. 2, Spanish. friedberg Kinot . Selections. 970-1070 1996 MSS 9-003 friedberg Mishnah c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-001 friedberg Talmud masekhet Shabbat Byzantium? c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-002 MSS 01244 Greek Gospels Constantinople? c. 1050 1901 (Codex Torontonensis) MSS 05316 Greek Gospel lectionary Constantinople? c. 1050 2011 friedberg Siddur Askenaz, Late 12 th 1996 MSS 3-015 century MSS 05314 Homeliae de tempore, de France? 1150-1200? 2005 sanctis, et de communi sanctorum MSS 05321 Hugh of Fouilloy. France? c. 1153 2011 De claustro animae MSS 03369 Hugh of StVictor Spain, c. 1175 2015 In Salomonis Ecclesiasten homiliæ MSS 04239 Cistercian Gospel Lectionary Spain, c. 1185 2012 friedberg Perush Neviʼim u-Khetuvim Ashkenaz, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-006 friedberg Zidkiyahu figlio di Abraham, Italy, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-012 ha-Rofè. Shibole ha-leḳeṭ friedberg David Kimhi. Spain or N. Africa, 13th 1996 MSS 5-010 Sefer ha-Shorashim century friedberg Ketuvim Spain, 13th century 1996 MSS 5-004 friedberg Beʼur ḳadmon le-Sefer ha- 13th century 1996 MSS 3-017 Riḳmah MSS 04404 William de Wycumbe. Llantony Secunda?, c. 1966 Vita venerabilis Roberti Herefordensis 1200 MSS 04008 Liber quatuor evangelistarum Avignon? c. 1220 1901 MSS 04240 Biblia Latina England, c. -

The Contribution of Spanish Jewryto the World of Jewishlaw*

THE CONTRIBUTION OF SPANISH JEWRYTO THE WORLD OF JEWISHLAW* Menachem Elon Spanish Jewry's contribution to post-Talmudie halakhic literature may be explored in part in The Digest of the Responsa Literature of Spain and North Africa, a seven-volume compilation containing references to more ? than 10,000 Responsa answers to questions posed to the authorities of the day. Another source of law stemming from Spanish Jewrymay befound in the community legislation (Takanot HaKahal) enacted in all areas of civil, public-administrative, and criminal law. Among themajor questions con sider edhere are whether a majority decision binds a dissenting minority, the nature of a majority, and the appropriate procedures for governance. These earlier principles of Jewish public law have since found expression in decisions of the Supreme Court of the State of Israel. *This essay is based on the author's presentation to the Biennial Meeting of the Board of Trustees of the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture, Madrid, June 27, 1992. JewishPolitical Studies Review 5:3-4 (Fall 1993) 35 This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.82.205 on Tue, 27 Nov 2012 04:27:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 36 Menachem Elon The Contribution of Spanish Jewry to theWorld of Jewish Law The full significance of Spanish Jewry's powerful contribu tion to post-Talmudic halakhic literature demands a penetrating study. To appreciate the importance of Spanish Jewry's contri bution to the halakhic world, one need only mention, in chrono logical order, various halakhic authorities, most who lived in Spain throughout their lives, some who emigrated to, and some who immigrated from, Spain. -

The Formation of the Talmud

Ari Bergmann The Formation of the Talmud Scholarship and Politics in Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s Dorot Harishonim ISBN 978-3-11-070945-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-070983-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-070996-4 ISSN 2199-6962 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110709834 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020950085 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Ari Bergmann, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. The book is published open access at www.degruyter.com. Cover image: Portrait of Isaac HaLevy, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Isaac_halevi_portrait. png, „Isaac halevi portrait“, edited, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ legalcode. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Chapter 1 Y.I. Halevy: The Traditionalist in a Time of Change 1.1 Introduction Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s life exemplifies the multifaceted experiences and challenges of eastern and central European Orthodoxy and traditionalism in the nineteenth century.1 Born into a prominent traditional rabbinic family, Halevy took up the family’s mantle to become a noted rabbinic scholar and author early in life. -

Download File

Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ari Bergmann All rights reserved ABSTRACT Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann This dissertation is dedicated to a detailed analysis and comparison of the theories on the process of the formation of the Babylonian Talmud by Yitzhak Isaac Halevy and David Weiss Halivni. These two scholars exhibited a similar mastery of the talmudic corpus and were able to combine the roles of historian and literary critic to provide a full construct of the formation of the Bavli with supporting internal evidence to support their claims. However, their historical construct and findings are diametrically opposed. Yitzhak Isaac Halevy presented a comprehensive theory of the process of the formation of the Talmud in his magnum opus Dorot Harishonim. The scope of his work was unprecedented and his construct on the formation of the Talmud encompassed the entire process of the formation of the Bavli, from the Amoraim in the 4th century to the end of the saboraic era (which he argued closed in the end of the 6th century). Halevy was the ultimate guardian of tradition and argued that the process of the formation of the Bavli took place entirely within the amoraic academy by a highly structured and coordinated process and was sealed by an international rabbinical assembly. While Halevy was primarily a historian, David Weiss Halivni is primarily a talmudist and commentator on the Talmud itself. -

Curr 8-14 the Eternal Light

CURR 8-14 THE ETERNAL LIGHT Is it actually required by Jewish legal tradition that there be an eternal light in front of the ark? Would it be a serious violation if the light is extinguished when, let us say, it is necessary to change gas pipes or electrical connections? (From Vigdor Kavaler, Rodef Shalom Temple, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.) THE Eternal Light (ner tamid) is one of the most beloved symbols of the synagogue. When a synagogue is dedicated in modern times, one of the most impressive ceremonials is the first lighting of the Eternal Light. Since the use of an Eternal Light in the synagogue is based upon the Eternal Light commanded by God of Moses for the Tabernacle (Exodus 27:20 and Leviticus 24:2), one would imagine that this beloved symbol, with such ancient roots, would continually come up for discussion in the long sequence of Jewish legal literature. Yet the astonishing fact is that it is not mentioned at all as part of the synagogue appurtenances in any of the historic codes, the Mishnah, the Talmud, the Shulchan Aruch, or the others. One might say there is not a single classic mention of it (as far as I can find). All the references that are usually cited as referring to an Eternal Light actually refer to an occasional light in the synagogue or else, more generally, to lights lit all over the synagogue during services, but not specifically in front of the Ark. This is the case with the various references in the Midrash. Numbers Rabba 4:20 speaks of the merit of Peultai (mentioned in I Chronicles 26:5) who lit a light before the Ark in the Temple in the morning and then again in the evening. -

Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books in the Library of Congress

Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books at the Library of Congress A Finding Aid פה Washington D.C. June 18, 2012 ` Title-page from Maimonides’ Moreh Nevukhim (Sabbioneta: Cornelius Adelkind, 1553). From the collections of the Hebraic Section, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. i Table of Contents: Introduction to the Finding Aid: An Overview of the Collection . iii The Collection as a Testament to History . .v The Finding Aid to the Collection . .viii Table: Titles printed by Daniel Bomberg in the Library of Congress: A Concordance with Avraham M. Habermann’s List . ix The Finding Aid General Titles . .1 Sixteenth-Century Bibles . 42 Sixteenth-Century Talmudim . 47 ii Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books in the Library of Congress: Introduction to the Finding Aid An Overview of the Collection The art of Hebrew printing began in the fifteenth century, but it was the sixteenth century that saw its true flowering. As pioneers, the first Hebrew printers laid the groundwork for all the achievements to come, setting standards of typography and textual authenticity that still inspire admiration and awe.1 But it was in the sixteenth century that the Hebrew book truly came of age, spreading to new centers of culture, developing features that are the hallmark of printed books to this day, and witnessing the growth of a viable book trade. And it was in the sixteenth century that many classics of the Jewish tradition were either printed for the first time or received the form by which they are known today.2 The Library of Congress holds 675 volumes printed either partly or entirely in Hebrew during the sixteenth century. -

Sexual Relations Between Jews and Muslims in Spain According to the Responsum 18:13 of Rabbi Asher Ben Jehiel Nadezda Koryakina (Université De Nantes, RELMIN)

NOVEMBER 6TH, 2013 RELMIN WORKSHOP Liens familiaux et vie sexuelle en sociétés pluriconfessionnelles : quelles conséquences juridiques ? Family bonding and sexual practices in multiconfessionnal societies: what judicial consequences? Contact : [email protected] Sexual relations between Jews and Muslims in Spain according to the responsum 18:13 of rabbi Asher ben Jehiel Nadezda Koryakina (Université de Nantes, RELMIN) NB : les textes et articles distribués ici demeurent la propriété de leur auteur, ils ne peuvent être reproduits ou utilisés sans leur accord préalable. NB: the papers and articles circulated for this event remain the property of their author. They may not be reproduced or otherwise used without their prior consent. Sexual relations between Jews and Muslims in Spain according to the responsum 18:13 of rabbi Asher ben Jehiel Koryakina Nadezda RELMIN The text and its author. This paper discusses a responsum authored by rabbi Asher ben Jehiel (1250 – 1328) who was a commentator on the Talmud and a judicial authority in both Ashkenaz and Sephardi communities in the 13th century and throughout the entire medieval period. Born in Rhineland about 1250, he later emigrated to southern France and then to Toledo, Spain, where he became a rabbi and lived until his death in 1328. The text in question deals with the judgment delivered on a Jewish widow who had sexual relations with a Muslim and conceived two children with him. Her conduct provoked hostility of the Jewish community of Cuenca in Spain and she was finally condemned to severe corporal punishment (cutting off her nose) and ordered to pay a fine to the Christian authorities of the city. -

You Shall Fear My Temple

And If A Soul Makes an Offering Parshas Vayikra The Chasid was stunned; all the way from Jerusalem to "Aharon's descendants, the Kohanim" that a poor person's Warsaw he had excitedly anticipated spending time with his offering is not eaten in public, so as not to shame him by Rebbe's son, but this was completely unexpected. He was displaying his “meager” offering. standing in the market in the middle of Warsaw with the Rebbe's son, as they listened to a woman Another source in our parsha expresses for a very long time. the same idea: "And if his sacrifice to the Lord, is a burnt offering from birds… Rabbi David Minsberg had awoken very And he shall split it open with its wing early that morning, as he did every day. On feathers."3 The Midrash says: "Here, it his way into town he met Rabbi Aharon refers to the actual feathers of its Biderman, son of the Karlin Rebbe. He was wings. But surely even a person who is surprised to meet him at such an early not particular, who, when smelling the hour, and speaking to a woman as well. He odor of burnt feathers, does not find it continued on, and later on in the day repulsive? Why then does Scripture returned to the same spot to find Reb command us to send the feathers up in Aharon still standing and listening to the woman who was smoke? The feathers are left intact so that the altar should repeating the same things over and over. -

Critical Philosophy of Halakha (Jewish Law): the Justification of Halakhic Norms And

Critical Philosophy of Halakha (Jewish Law): The Justification of Halakhic Norms and Authority Yonatan Yisrael Brafman Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Yonatan Yisrael Brafman All rights reserved ABSTRACT Critical Philosophy of Halakha (Jewish Law): The Justification of Halakhic Norms and Authority Yonatan Brafman Contemporary conflicts over such issues as abortion, same-sex marriage, circumcision, and veiling highlight the need for renewed reflection on the justification of religious norms and authority. While abstract investigation of these questions is necessary, inquiry into them is not foreign to religious traditions. Philosophical engagement with these traditions of inquiry is both intellectually and practically advantageous. This does not demand, however, that these discussions be conducted within a discourse wholly internal to a particular religious tradition; dialogue between a religious tradition and philosophical reflection can be created that is mutually beneficial. To that end, this dissertation explores a central issue in philosophy of halakha (Jewish law): the relation between the justification of halakhic norms and halakhic-legal practice. A central component of philosophy of halakha is the project of ta’amei ha-mitzvot (the reasons for the commandments). Through such inquiry, Jewish thinkers attempt to demonstrate the rationality of Jewish religious practice by offering reasons for halakhic norms. At its best, it not only seeks to justify halakhic norms but also elicits sustained reflection on issues in moral philosophy, including justification and normativity. Still, there is a tendency among its practitioners to attempt to separate this project from halakhic-legal practice. -

Passover Haggadah; ISAAC BEN MEIR HA-LEVI DUEREN, Sha'arei

Passover Haggadah; ISAAC BEN MEIR HA-LEVI DUEREN, Sha‘arei dura [The Gates of Dueren] (table of contents only) In Hebrew, manuscript on parchment Northern France or Germany, late 14th-early 15th centuries 22 folios on parchment, unfoliated (collation i8 [-1 and 2] ii-iii8), decorated catchwords on several folio rectos and versos, ruled in blind, remnants of prickings in upper margin on ff. 18-22 (justification 100 x 75 mm.), ff. 1-21, the Passover Haggadah, written in neat square (body of Haggadah) and semi-cursive (commentary) Ashkenazic scripts in dark brown ink in seventeen lines of Haggadah text throughout (except when commentary interferes), ff. 21v-22v, table of contents of Sha‘arei dura, written in neat semi-cursive Ashkenazic script in dark brown ink in eighteen lines throughout, enlarged incipits, partial vocalization on ff. 1, 4v-5, diagram in commentary on f. 10, marginalia in hand of primary scribe in lighter brown ink on ff. 17-19, periodic justification of lines using verbal and ornamental space holders, slight staining on several folios, most noticeably on ff. 2v-3 (a wine stain in text that contains the blessing over wine), five-mm. slit on f. 12 not affecting text, two wormholes on ff. 16-17 not affecting legibility of text, two words partially erased and bored through on f. 17, trimmed at outer margins with loss of some marginalia on ff. 17-18. Bound in modern blind-tooled calf, title and subtitle on spine and front cover, respectively, in gilt, marbled flyleaves and pastedowns, spine with five raised bands forming five compartments, blind-tooled modern calf slipcase lined with marbled paper. -

Outline of Knowledge Database

Outline of Judaism January 2, 2012 Contents SOCI>Religion>Religions>Judaism .................................................................................................................................. 1 SOCI>Religion>Religions>Judaism>Mystical ............................................................................................................. 1 SOCI>Religion>Religions>Judaism>Places................................................................................................................. 2 SOCI>Religion>Religions>Judaism>People ................................................................................................................ 2 SOCI>Religion>History>Judaism ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Note: To look up references, see the Consciousness Bibliography, listing 10,000 books and articles, with full journal and author names, available in text and PDF file formats at http://www.outline-of-knowledge.info/Consciousness_Bibliography/index.html. SOCI>Religion>Religions>Judaism Judaism Religions {Judaism} can be about loyalty to one tribal god, by following laws, rituals, and practices. god Judaism has only one God. In Judaism, Hebrews (wanderers) are God's chosen people. God commands that people love God and all other people. People should become like God in transcendence. No one can describe God in form or history. God does not state his purposes. resurrection Perhaps, at current-age end, God will raise people