Soledad Barrio & Noche Flamenca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Makes Music Credits

THE WORLD MAKES MUSIC CREDITS Director Margriet Jansen With Bert Boogaard Lucien Brazil Miriam Brenner Arne Broekhoven Karin Elich Sander Friedeman Bilal Gebara Els van der Linden Raj Mohan Achmed Sadat Merel Simons Lars de Wilde Director of Photography Marcel Prins Sound Jan Wouter Stam en Jillis Schriel Editor Diego Gutiérrez Supervising editor Danniel Danniel Fundraising Ineke Smits Music rights clearance Ruby van der Linden – Yourownrights Music & Publishing Agency RTV Utrecht Machteld Smits en Neske Kraai Post production Sound Sander Friedeman Metropolisfilm Titles Guido van Eekelen Metropolisfilm Colour grading Jef Grosfeld alias KID JEF Translation and subtitles Helene Reid Subtext Translations Producer Jean Hellwig Music works in order of appearances THE CLICK SONG (Qongqothwane) Miriam Makeba (1932 – 2008) composers and authors: Ronnie Modise Majola Sehume, Rufus Khoza, Dambuza Mdledle Nathan and Joseph Mogotsi publisher: Gallo Music Publishers administrated by Warner/Chappell Music Holland B.V. recordings: Oudejaarscompilatie 1979 (BNN/VARA) NIRAN Bixiga70 composer: Bixiga70 publisher: La Chunga Music Publishing / Edition Beatglitter recordings: RASA Utrecht, 2016 (Vista Far Reaching Visuals) OCUPAI Bixiga70 composer: Romulo Nardes, Cuca Ferreira and Bixiga 70 publisher: La Chunga Music Publishing / Edition Beatglitter recordings: RASA Utrecht, 2016 (Vista Far Reaching Visuals) FURAHI Zap Mama composer: Marie Daulne album: SABSYLMA, 1994 recordings: North Sea Jazz Festival 1997 (NPS) TANGO AL MAR Faiz ali Faiz, Duquende, Miguel -

Qawwali – Lobgesänge Aus Dem Punjab Faiz Ali Faiz & Party

WELTMUSIK IM MOZART SAAL 27 APR 2018 MOZART SAAL QAWWALI – LOBGESÄNGE AUS DEM PUNJAB FAIZ ALI FAIZ & PARTY 229154_WiMSaal_Punjab_27_4_18.indd9154_WiMSaal_Punjab_27_4_18.indd a 110.04.180.04.18 110:130:13 MIT FREUNDLICHER UNTERSTÜTZUNG HAUPTFÖRDERER Ermöglicht durch den Kulturfonds Frankfurt RheinMain im Rahmen des Schwerpunktthemas „Transit“ Das Konzert fi ndet ohne Pause statt IMPRESSUM Herausgeber: Alte Oper Frankfurt Konzert- und Kongresszentrum GmbH Opernplatz, 60313 Frankfurt am Main, www.alteoper.de Intendant und Geschäftsführer: Dr. Stephan Pauly Mitarbeit bei Programmentwicklung, Konzeption und Planung: Gundula Tzschoppe (Programm und Produktion Alte Oper), Birgit Ellinghaus Programmheftredaktion: Anne-Kathrin Peitz Konzept: hauser lacour kommunikationsgestaltung gmbh Satz und Herstellung: Druckerei Imbescheidt Bildnachweis: S. 5: Wikipedia, Ramkishan950; S. 8: Habib Hmima; S. 11: Lucien Lung 229154_WiMSaal_Punjab_27_4_18.indd9154_WiMSaal_Punjab_27_4_18.indd b 110.04.180.04.18 110:130:13 GRUSSWORT Nach dem erfolgreichen Projektstart in der Spielzeit 2016/17 bietet die Alte Oper bereits zum zweiten Mal der Vielfalt der Musikkulturen der Welt ein Forum im Mozart Saal. Ziel der Reihe ist es, das Ver- ständnis anderer Lebenswelten über ihre Musik zu fördern. Das diesjährige Musikfest-Motto „Fremd bin ich...“, an Schuberts epochalem Liederzyklus exemplifi ziert, schlägt gleichzeitig den Bogen zu den vier Konzerten mit Weltmusik im Mozart Saal. Beide Projekte, das Musikfest und die Weltmusik-Reihe, werden vom Kulturfonds Frankfurt RheinMain gefördert. Der Themenschwerpunkt „Transit“ des Kulturfonds geht damit in sein letztes Jahr. Seit dem Start des Themas 2015 haben sich Antrag- steller/innen in rund 70 Projekten aller Sparten mit dem Schwer- punktthema auseinandergesetzt. Die Alte Oper Frankfurt hat in mehreren größeren Konzertveranstaltungen die musikalischen Dimen- sionen des Themas „Transit“ ausgelotet und sich dabei auch über den angestammten europäischen Raum hinausbewegt. -

Social Responsability and Sustainability Report 2020 SA Social Responsability and Sustainability Report 2020

Social Responsability and Sustainability Report 2020 SA Social Responsability and Sustainability Report 2020 Our current circumstances, the extraordinarily complex and uncertain turn of events, leave little room for retrospective analy- sis. Our priority now must be to address both the serious health crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and, at the same time, the resulting profound social and economic crisis that has struck us all so suddenly. All without losing sight of the future. These are times for decisive, rigorous action, for acting with a sense of responsibility and with a long-term view. From the very outset, PRISA, aside from immediately implementing the required sanitary measures, saw its priority as maintain- ing its operations in the areas of quality education, news, culture and entertainment. We are convinced that this was a priority shared by all our target audiences. We have given equal priority to our financial liquidity and the adaptation of our structures, resources and processes to the rapidly changing new environment. Over the past year, the Board of Directors has devoted particular attention to reviewing strategy and to defining the optimum roadmap to ensure that our range of different operations can successfully develop future projects. These must necessarily be transformative – and, by extension, ambitious and exciting – and they must be in a position to generate value on a sustainable basis for all our publics and stakeholders. We also envisage profitability levels that will allow us to offer adequate returns to those who provide us with the necessary re- sources to develop our projects. This unprecedented crisis will have a negative effect on our already high level of indebtedness, which we must reduce and bring within parameters that are appropriate to our businesses. -

Expresiones Culturales Andaluzas

Expresiones culturales andaluzas Isidoro Moreno Juan Agudo [coordinadores] Patrocinan: © Los autores © De esta edición: Aconcagua Libros Sevilla, 2012 D.L.: SE 4569-2012 ISBN: 978-84-96178-96-0 Aconcagua Libros (Sevilla) E-mail: [email protected] www.aconcagualibros.net ÍNDICE A modo de presentación.................................................................................7 La identidad cultural de Andalucía. Isidoro Moreno................................11 El habla andaluza: descripción y valoración sociolingüística. Miguel Ropero Núñez.....................................................................................35 Espacios de sociabilidad y arquitectura tradicional. Juan Agudo............63 Sociabilidad, relaciones de poder y cultura política en Andalucía. Javier Escalera Reyes......................................................................................127 Las fiestas andaluzas.Isidoro Moreno y Juan Agudo..................................165 El flamenco.Cristina Cruces Roldán...........................................................219 Las actividades artesanas en Andalucía: economía y cultura del trabajo manual. Esther Fernández de Paz.....................................................283 Autores.....................................................................................................319 A modo de presentación Isidoro Moreno y Juan Agudo (editores) La colaboración prestada por el Centro de Estudios Andaluces nos ha dado la oportu- nidad de preparar dos volúmenes en los que, de forma complementaria, -

Breathtaking Tragedy at Noche Flamenca by Kalila Kingsford Smith

Photo: Chris Bennion Breathtaking Tragedy at Noche Flamenca by Kalila Kingsford Smith Antigona is full of breathtaking, powerful moments. A collaboration between Soledad Barrio & Noche Flamenca and theater director Lee Breuer, the production is based on Sophocles’ heroine Antigone, who is sentenced to be buried alive in a cave after fulfilling the sacred duty of burying her brother, who died a rebel. The story is told equally through the music, the song, and the dance, as is traditional in the flamenco form. In this interpretation of the Greek tragedy, the chorus wears masks, obscuring the performers’ identities and yet intensifying the expression of each emotion. As in an opera, translations are projected onto a scrim upstage to help convey the narrative to those who don’t understand Spanish. However, I hardly glance at them; my eyes never stray from the dancers, and I understand without reading the text the raw emotion within la canción. Our first vision of this Spanish/Greek universe is black silk pouring down towards the stage, silk held in place by a man standing on a tall platform obscured by the darkness. He ripples the fabric in time with the strumming of the guitar, catching the light like glimmers on a river. Slowly we see shapes pressing into the silk, the crouched bodies of the chorus emerging from the darkness one arm at a time. Then we see the masks—blindingly white against the black river—demons that crawl, reach, and writhe in a clump of faces. Typically, one wouldn’t see movement so close to the ground in a flamenco production, but I am enthralled by the eeriness of this image. -

Edinburgh International Festival Society Papers

Inventory Acc.11779 Edinburgh International Festival Society Papers National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland BOX 1 1984 1. Venue letting contracts. 2. Australian Youth Orchestra. 3. BBC Orchestra. 4. Beckett Clurman. 5. Black Theatre 6. Boston Symphony 7. Brussels Opera 8. Childrens Music Theatre 9. Coleridges Ancient Mariner 10. Hoffung Festival BOX 2 1984 11. Komische Opera 12. Cleo Laine 13. LSO 14. Malone Dies 15. Negro Ensemble 16. Philharmonia 17. Scottish National 18. Scottish Opera 19. Royal Philharmonic 20. Royal Thai Ballet 21. Teatro Di San Carlo 22. Theatre de L’oeuvre 23. Twice Around the World 24. Washington Opera 25. Welsh National Opera 26. Broadcasting 27. Radio Forth/Capital 28. STV BOX 2 1985 AFAA 29. Applications 30. Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra/Netherlands Chamber Orchestra 31. Balloon Festival. 32. BBC TV/Radio. 33. Le Misanthrope – Belgian National Theatre 34. John Carroll 35. Michael Clark. BOX 3 36. Cleveland Quartet 37. Jean Phillippe Collard 38. Compass 39. Connecticut Grand Opera 40. Curley 41. El Tricicle 42. EuroBaroque Orchestra 43. Fitzwilliam 44. Rikki Fulton 45. Goehr Commission 46. The Great Tuna 47. Haken Hagegard and Geoffery Parons 48. Japanese Macbeth 49. .Miss Julie 50. Karamazous 51. Kodo 52. Ernst Kovacic 53. Professor Krigbaum 54. Les Arts Florissants. 55. Louis de France BOX 4 56. London Philharmonic 57. Lo Jai 58. Love Amongst the Butterflies 59. Lyon Opera 60. L’Opera de Nice 61. Montreal Symphony Orchestra 62. -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

Estrella Morente Lead Guitarist: José Carbonell "Montoyita"

Dossier de prensa ESTRELLA MORENTE Vocalist: Estrella Morente Lead Guitarist: José Carbonell "Montoyita" Second Guitarist: José Carbonell "Monty" Palmas and Back Up Vocals: Antonio Carbonell, Ángel Gabarre, Enrique Morente Carbonell "Kiki" Percussion: Pedro Gabarre "Popo" Song MADRID TEATROS DEL CANAL – SALA ROJA THURSDAY, JUNE 9TH AT 20:30 MORENTE EN CONCIERTO After her recent appearance at the Palau de la Música in Barcelona following the death of Enrique Morente, Estrella is reappearing in Madrid with a concert that is even more laden with sensitivity if that is possible. She knows she is the worthy heir to her father’s art so now it is no longer Estrella Morente in concert but Morente in Concert. Her voice, difficult to classify, has the gift of deifying any musical register she proposes. Although strongly influenced by her father’s art, Estrella likes to include her own things: fados, coplas, sevillanas, blues, jazz… ESTRELLA can’t be described described with words. Looking at her, listening to her and feeling her is the only way to experience her art in an intimate way. Her voice vibrates between the ethereal and the earthly like a presence that mutates between reality and the beyond. All those who have the chance to spend a while in her company will never forget it for they know they have been part of an inexplicable phenomenon. Tonight she offers us the best of her art. From the subtle simplicity of the festive songs of her childhood to the depths of a yearned-for love. The full panorama of feelings, the entire range of sensations and colours – all the experiences of the woman of today, as well as the woman of long ago, are found in Estrella’s voice. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

FDLI Library

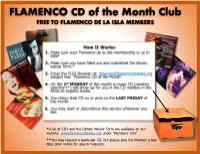

FLAMENCO CD of the Month Club FREE TO FLAMENCO DE LA ISLA MEMBERS *A list of CD’s and the Library Waiver Form are available on our website: www.flamencodelaisla.org under “Members Info” **You may request a particular CD, but please give the librarian a few days prior notice for special requests. FLAMENCO DE LA ISLA SOCIETY RESOURCE LIBRARY DVDs DVD Title: Approx. Details length: Arte y Artistas Flamencos 0:55 Eva La Yerbabuena; Sara Baras; Beatriz Martín Baile Flamenco 1:30 Joaquin Grilo – Romeras; Concha Vargas – Siguiriyas; Maria Pagés – Garrotín; Lalo Tejada – Tientos; Milágros Mengíbar – Tarantos; La Tona – Caracoles; Ana Parilla – Soleares; Carmelilla Montoya - Tangos Bulerías (mixed) 1:22 Caminos Flamenco Vol. 1 1:08 Caminos Flamenco Vol. 2 0:55 Carlos Saura’s Carmen 1:40 Antonio Gades, Laura del Sol, Paco de Lucia Familia Carpio 1:12 Flamenco 1:40 Carlos Saura Flamenco at 5:15 0:30 National Ballet School of Canada Flamenco de la Luz 1:45 Flamenco de la Luz; Una Noche de la Luz; Women artists Gracia del Baile Flamenco 0:40 Gyspy Heart 0:45 Joaquin Cortés y Pasiόn Gitana 1:38 La Chana 0:45 Latcho Drome 1:40 The Life and music of Manuel de Falla 1:15 Montoyas y Tarantos 1:40 Noche Flamenca 0:55 Noche Flamenca Vol. 5 1:00 Nuevo Flamenco Ballet Fury 1:11 Paco Peña’s Misa Flamenco 0:52 "Unique combination of the religious Mass and Flamenco singing and dancing…" [cover] Queen of the Gypsies - Carmen Amaya 1:40 Rito y Geografía del Baile Vol. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

In the Realm of Politics, Nonsense, and the Absurd: the Myth of Antigone in West and South Slavic Drama in the Mid-Twentieth Century

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4312/keria.20.3.95-108 Alenka Jensterle-Doležal In the Realm of Politics, Nonsense, and the Absurd: The Myth of Antigone in West and South Slavic Drama in the Mid-Twentieth Century Throughout history humans have always felt the need to create myths and legends to explain and interpret human existence. One of the classical mythi- cal figures is ancient Antigone in her torment over whether to obey human or divine law. This myth is one of the most influential myths in European literary history. In the creation of literature based on this myth there have always been different methods and styles of interpretation. Literary scholars always emphasised its philosophical and anthropological dimensions.1 The first variants of the myth of Antigone are of ancient origin: the playAntigone by Sophocles (written around 441 BC) was a model for others throughout cultural and literary history.2 There are various approaches to the play, but the well-established central theme deals with one question: the heroine Antigone is deeply convinced that she has the right to reject society’s infringement on her freedom and to act, to recognise her familial duty, and not to leave her brother’s body unburied on the battlefield. She has a personal obligation: she must bury her brother Polyneikes against the law of Creon, who represents the state. In Sophocles’ play it is Antigone’s stubbornness transmitted into action 1 Cf. also: Simone Fraisse, Le mythe d’Antigone (Paris: A. Colin, 1974); Cesare Molinari, Storia di Antigone da Sofocle al Living theatre: un mito nel teatro occidentale (Bari: De Donato, 1977); George Steiner, Antigones (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984); Elisabeth Frenzel, Stoffe der Weltlitera- tur: Ein Lexikon Dichtungsgeschichtlicher Längsschnitte, 5.