Transexperience and Chinese Experimental Art, 1990–2000 By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biting the Big Apple

Biting the Big Apple Curator Nicholas Baume talks to Fran Molloy lumnus Nicholas Baume has a new gallery space to curate: New York City. He has recently been art appointed Director and AChief Curator of the New York Public Art Fund, where he will guide the selection and installation of artworks by established and emerging artists in public spaces throughout the city. “The role does make me look at New York in a different way,” Baume says. “I’m really excited about it.” This is also the first time Baume has lived in New York, though his “Nicholas is like a son to me,” my lot in a professional direction, long association with the city’s cultural Kaldor says. “He is a brilliant young I felt that education for its own landscape started with a high school man who is very passionate about art.” sake was a very valuable thing.” art club trip in the early ’80s while an Baume and his two brothers were Baume has fond memories of his exchange student in Houston, Texas. similar in age and close friends with time at the University. “It was the first Graduating from the University Kaldor’s sons and spent a lot of time time I felt I was in an environment in 1987 with joint honours in Fine at the Kaldor home. But while his that nourished my intellectual Arts and Philosophy, Baume became brothers preferred the swimming and creative development. I loved an influential Australian curator, pool, Nicholas was drawn to Kaldor’s discovering the world of ideas.” exhibiting such artists as Andy extraordinary art collection. -

Joan Lebold Cohen Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JOAN LEBOLD COHEN Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:31 Oct 2009 Duration: about 2 hours Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): It would be great if you could speak a little bit about how you got to China, when you got to China – with dates specific to the ‘80s, and how you saw the 80’s develop. From your perspective what were some of the key moments in terms of the arts? Joan Lebold Cohen (JC): First of all, I should say that I had been to China three times before the 1980s. I went twice in 1972, once on a delegation in May for over three weeks, which took us to Beijing, Luoyang, Xi’an, and Shanghai and we flew into Nanchang too because there were clouds over Guangzhou and the planes couldn’t fly in. This was a period when, if you wanted to have a meal and you were flying, the airplane would land so that you could go to a restaurant (Laughter). They were old, Russian airplanes, and you sat in folding chairs. The conditions were rather…primitive. But I remember going down to the Shanghai airport and having the most delicious ‘8-precious’ pudding and sweet buns – they were fantastic. I also went to China in 1978. For each trip, I had requested to meet artists and to go to exhibitions, but was denied the privilege. However, there was one time, when I went to an exhibition in May of 1972 and it was one of the only exhibitions that exhibited Cultural Revolution model paintings; it was very amusing. -

BILLY SULLIVAN *1946 in New York, USA Lives and Works in New York City

BILLY SULLIVAN *1946 in New York, USA Lives and works in New York City Education Depuis 1788 1968 School of Visual Arts, New York, NY, USA 1964 High School of Art and Design, New York, NY, USA Freymond-Guth Fine Arts Riehenstrasse 90 B Teaching CH-4058 Basel T +41 (0)61 501 9020 1997 The School of Visual Arts, New York: BFA Photo Thesis offi[email protected] 2012–14 New York University: MFA Program, Studio Art, Steinhardt School of www.freymondguth.com Culture, Education, and Human Development 2003–06, New York University, Interactive Telecommunication Program 2010–14 1999 Harvard University, The Department of Visual and Environmental Studies Solo Shows (selection) 2016 Monteverdi Art Gallery, Sarteano, Tuscany, curated by Sarah McCrory kaufmann repetto, New York 2015 Ille Arts, Amagansett, NY, USA 2014 Time after Time, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Blush, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, DE 2012 Bird Drawings, Glenn Horowitz Bookseller, East Hampton, NY, USA Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2011 Still, Looking, Kaufmann Repetto, Milan, IT Now & Then, Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO, USA 2010 Susanne Hilberry Gallery, Ferndale, MI, USA East End Photographs 1973-2009, Salomon Contemporary, East Hampton, NY, USA 2009 Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, DE Conversations, Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2008 Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA, USA Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH, USA Texas Gallery, Houston, TX, USA 2007 Guild Hall, East Hampton, NY, USA Galleria Francesca Kaufmann, Milan, IT 2006 New Work, Rebecca Ibel Gallery, -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

New China and Its Qiaowu: the Political Economy of Overseas Chinese Policy in the People’S Republic of China, 1949–1959

1 The London School of Economics and Political Science New China and its Qiaowu: The Political Economy of Overseas Chinese policy in the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1959 Jin Li Lim A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, September 2016. 2 Declaration: I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98,700 words. 3 Abstract: This thesis examines qiaowu [Overseas Chinese affairs] policies during the PRC’s first decade, and it argues that the CCP-controlled party-state’s approach to the governance of the huaqiao [Overseas Chinese] and their affairs was fundamentally a political economy. This was at base, a function of perceived huaqiao economic utility, especially for what their remittances offered to China’s foreign reserves, and hence the party-state’s qiaowu approach was a political practice to secure that economic utility. -

Chinese Contemporary Art and the Value of Dissidence by Marie

Transition and Transformation: Chinese Contemporary Art and the Value of Dissidence by Marie Dorothée Leduc A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Visual Art and Globalization Department of Sociology and Art and Design University of Alberta © Marie Leduc, 2016 Abstract Transition and Transformation: Chinese Contemporary Art and the Value of Dissidence Marie Leduc Taking an interdisciplinary approach combining sociology and art history, this dissertation considers the phenomenal rise of Chinese contemporary art in the global art market since 1989. The dissertation explores how Western perceptions of difference and dissidence have contributed to the recognition and validation of Chinese contemporary art. Guided by Nathalie Heinich’s sociology of values and Pierre Bourdieu’s work on the field of cultural production, the dissertation proposes that dissidence may be understood as an artistic value, one that distinguishes artists and artwork as singular and original. Following the careers of nine Chinese artists who moved to France in and around 1989, the dissertation demonstrates how perceptions of dissidence – artistic, cultural, and political – have distinguished Chinese artists as they have transitioned into an artistic field dominated by Western liberal-democratic values and artistic taste. The transition and transformation of Chinese contemporary art and artists then highlights how the valorization of dissidence in the West is both artistic and political, and significant to the production of contemporary art. ii Preface This thesis is an original work by Marie Leduc. The research project, of which this thesis is a part, received research ethics approval from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board, Project Name “Transition and Transformation: Contemporary Chinese Art in the Global Marketplace,” No. -

Deng Xiaoping in the Making of Modern China

Teaching Asia’s Giants: China Crossing the River by Feeling the Stones Deng Xiaoping in the Making of Modern China Poster of Deng Xiaoping, By Bernard Z. Keo founder of the special economic zone in China in central Shenzhen, China. he 9th of September 1976: The story of Source: The World of Chinese Deng Xiaoping’s ascendancy to para- website at https://tinyurl.com/ yyqv6opv. mount leader starts, like many great sto- Tries, with a death. Nothing quite so dramatic as a murder or an assassination, just the quiet and unassuming death of Mao Zedong, the founding father of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In the wake of his passing, factions in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) competed to establish who would rule after the Great Helmsman. Pow- er, after all, abhors a vacuum. In the first corner was Hua Guofeng, an unassuming functionary who had skyrocketed to power under the late chairman’s patronage. In the second corner, the Gang of Four, consisting of Mao’s widow, Jiang September 21, 1977. The Qing, and her entourage of radical, leftist, Shanghai-based CCP officials. In the final corner, Deng funeral of Mao Zedong, Beijing, China. Source: © Xiaoping, the great survivor who had experi- Keystone Press/Alamy Stock enced three purges and returned from the wil- Photo. derness each time.1 Within a month of Mao’s death, the Gang of Four had been imprisoned, setting up a showdown between Hua and Deng. While Hua advocated the policy of the “Two Whatev- ers”—that the party should “resolutely uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made and unswervingly follow whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave”—Deng advocated “seek- ing truth from facts.”2 At a time when China In 1978, some Beijing citizens was reexamining Mao’s legacy, Deng’s approach posted a large-character resonated more strongly with the party than Hua’s rigid dedication to Mao. -

Contemporary Chinese Art

FRICK FINE ARTS LIBRARY ART HISTORY: CONTEMPORARY CHINESE ART Library Guide Series, No. 44 “Qui scit ubi scientis sit, ille est proximus habenti.” -- Brunetiere* This bibliography is highly selective and is meant only as a starting place to aid the beginning art history student in his/her search for library material. The serious student will find other relevant sources by noting citations within the encyclopedias, books, journal articles, and other sources listed below in addition to searching Pitt Cat, the ULS online catalog. IMPORTANT: For scholars who read Chinese, please note that the resources on this library guide are primarily in Western languages. Chinese language materials can be searched in Pitt Cat Classic using Pinyin. Reference assistance with Chinese language materials is available at the East Asian Library on the 2nd floor of Hillman Library. Before Beginning Research FFAL Hours: M-H, 9-9; F, 9-5; Sa-Su, Noon - 5 Policies Requesting Items: All ULS libraries allow you to request an item that is in the ULS Storage Facility or has not yet been cataloged at no charge by using the “Get It” Icon in Pitt Cat Plus. Items that are not in the Pitt library system may also be requested from another library that owns them via the same icon in the online catalog. There is a $5.00 feel for photocopying journal articles (unless they are sent to the student via email). Requesting books from another library is free of charge. Photocopying and Printing: There are two photocopiers and one printer in the FFAL Reference Room. One photocopier accepts cash (15 cents per copy) and both are equipped with a reader for the Pitt ID debit card (10 cents per copy). -

Leading Cultural Figures Attend Asia Society Art Gala, Launching Art Basel in Hong Kong

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE LEADING CULTURAL FIGURES ATTEND ASIA SOCIETY ART GALA, LAUNCHING ART BASEL IN HONG KONG GUESTS INCLUDED ROBERT AND CHANTAL MILLER, JULIA AND VICTOR FUNG & BASSAM SALEM THIS YEAR’S HONOUREES FEATURED BHARTI KHER, LIU GUOSONG, TAKASHI MURAKAMI & ZHANG XIAOGANG (Hong Kong, 15 May 2014) More than four hundred of the world’s most distinguished collectors, curators, gallerists and dignitaries gathered this evening to honor four exceptional contemporary artists at the Asia Society’s second annual Art Gala, hosted by Ms. S. Alice Mong and Dr. Melissa Chiu at their spectacular Hong Kong Center. Kicking off Art Basel in Hong Kong, the evening celebrated world-renowned artists Bharti Kher, Liu Guosong, Takashi Murakami and Zhang Xiaogang for their extraordinary contributions to contemporary art in Asia. Guests were also treated to a private viewing of the first major solo exhibition of Xu Bing’s work in Hong Kong, currently on display through 31 August 2014. Notable guests included artists Li Songsong, Mariko Mori, Michael Joo and Song Dong. International collectors attended, including Deddy Kusama, Basma Al Sulaiman, Maggie Tsai, Alexandra Prasetio, and Bharat and Swati Bhise. Gallerists present included Nick Simunovic of Gasgosian Gallery, one of the evening’s hosts, Rachel Lehmann, Emmanuel Perrotin, Arne Glimcher, Marcia Levine, and Jane Lombard and Lisa Carlson. Supporters of Asia Society included Robert and Chantal Miller, Hal and Ruth Newman, Mitch and Joleen Julis. Other guests included actress Lynn Hsieh, Nam June Paik’s Nephew, Ken Hakuta, Director of Art Basel, Marc Spiegler, Managing Director of Christie’s Asia, Rebecca Wei, and Curator of UBS Art Collection, Stephen McCoubrey. -

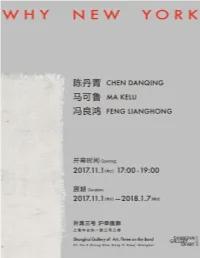

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin

“Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 ABSTRACT “Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 Copyright by Muyun Zhou 2021 Abstract In his world literature lecture series running from 1989 to 1994, the Chinese diasporic writer-painter Mu Xin (1927-2011) provided a puzzling proposition for a group of emerging Chinese artists living in New York: “Art is to sacrifice.” Reading this proposition in tandem with Mu Xin’s other comments on “sacrifice” from the lecture series, this study examines the intricate relationship between aesthetics and ethics in Mu Xin’s project of art. The question of diasporic positionality is inherent in the relationship between aesthetic and ethical discourses, for the two discourses were born in a Western tradition, once foreign to Mu Xin. -

No Ordinary Joe! New President Joe Preston and His Wife, Joni

LIONMAGAZINE.ORG JULY/AUGUST 2014 No Ordinary Joe! New President Joe Preston and his wife, Joni Don’t Run Out of Money During Retirement What Investors Should Worry About It’s no secret that the vast majority of Americans entering their retirement years are doing so with vastly underfunded retirement savings. However, even if you have signifi cant fi nancial assets in your retirement savings, assets in excess of $500,000, your hope for a comfortable retirement is hardly assured. In fact, you could be headed for a fi nancial disaster just when you can least aff ord it. And that’s why you should request a free copy of Fisher Investments’ Th e 15-Minute Retirement Plan: How to Avoid Running Out of Money When You Need It Most. Unlike most retirement advice, this guide is written for people with investible assets of $500,000 or more. You’ll be surprised at what you might learn and how much you might benefi t. I want to send you Th e Th e 15-Minute Retirement Plan is loaded with practical information that you 15-Minute Retirement Plan can use to help meet your personal fi nancial goals in retirement. Specifi cally, because it contains valuable you’ll learn: information you can use to • Th e truth about how long your nest egg can last help attain one of life’s most • How much you can safely take as income each year important assets: fi nancial • How infl ation can wreak havoc with your plan and how to deal with it peace of mind.