The Origin of Mayan Syllabograms and Orthographic Conventions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ka И @И Ka M Л @Л Ga Н @Н Ga M М @М Nga О @О Ca П

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3319R L2/07-295R 2007-09-11 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, SEI (Universal Scripts Project) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3292 Date: 2007-09-11 1. Introduction. The Javanese script, or aksara Jawa, is used for writing the Javanese language, the native language of one of the peoples of Java, known locally as basa Jawa. It is a descendent of the ancient Brahmi script of India, and so has many similarities with modern scripts of South Asia and Southeast Asia which are also members of that family. The Javanese script is also used for writing Sanskrit, Jawa Kuna (a kind of Sanskritized Javanese), and Kawi, as well as the Sundanese language, also spoken on the island of Java, and the Sasak language, spoken on the island of Lombok. Javanese script was in current use in Java until about 1945; in 1928 Bahasa Indonesia was made the national language of Indonesia and its influence eclipsed that of other languages and their scripts. Traditional Javanese texts are written on palm leaves; books of these bound together are called lontar, a word which derives from ron ‘leaf’ and tal ‘palm’. 2.1. Consonant letters. Consonants have an inherent -a vowel sound. Consonants combine with following consonants in the usual Brahmic fashion: the inherent vowel is “killed” by the PANGKON, and the follow- ing consonant is subjoined or postfixed, often with a change in shape: §£ ndha = § NA + @¿ PANGKON + £ DA-MAHAPRANA; üù n. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Pictograms: Purely Pictorial Symbols

toponymy course 10. Writing systems Ferjan Ormeling This chapter shows the semantic, phonetic and graphic aspects of language. It traces the development of the graphic aspects from Sumeria 3500BC, from logographic or ideographic via syllabic into alphabetic scripts resulting in a number of script families. It gives examples of the various scripts in maps (see underlined script names) and finally deals with combination of scripts on maps. 03/07/2011 1 Meaning, sound and looks What is the name? - Is it what it means? - Is it what it sounds? - Is it what it looks? 03/07/2011 2 Meaning: the semantic aspect As long as a name is what it means, both its sound and its looks (spelling) are only relevant as far as they support the meaning. The name ‘Nederland’ is wat it means to our neighbours: ‘Low country’. So they translate it for instance into ‘Pays- Bas’ (French) or Netherlands (English) or Niederlande (German), even though that does neither sound nor look like ‘Nederland’. To Romans and Italians, however, the names Qart Hadasht and Neapolis had never been what they meant (‘new towns’). So they became what they sounded: Carthago (to the Roman ear) and Napoli. 03/07/2011 3 Sound: the phonetic aspect As soon as a name is what it sounds, its meaning has become irrelevant. Its looks (spelling) then may or may not be adapted to its sound. The dominance of the phonetic aspect to a name (the ‘oral tradition’) allows the name to degenerate graphically. Eventually, the name may be adapted semantically to its perceived sound, through a process called ‘popular etymology’. -

The Origin of the Alphabet: an Examination of the Goldwasser Hypothesis

Colless, Brian E. The origin of the alphabet: an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis Antiguo Oriente: Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Vol. 12, 2014 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la Institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Colless, Brian E. “The origin of the alphabet : an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis” [en línea], Antiguo Oriente : Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente 12 (2014). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/origin-alphabet-goldwasser-hypothesis.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] . 03 Colless - Alphabet_Antiguo Oriente 09/06/2015 10:22 a.m. Página 71 THE ORIGIN OF THE ALPHABET: AN EXAMINATION OF THE GOLDWASSER HYPOTHESIS BRIAN E. COLLESS [email protected] Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Summary: The Origin of the Alphabet Since 2006 the discussion of the origin of the Semitic alphabet has been given an impetus through a hypothesis propagated by Orly Goldwasser: the alphabet was allegedly invented in the 19th century BCE by illiterate Semitic workers in the Egyptian turquoise mines of Sinai; they saw the picturesque Egyptian inscriptions on the site and borrowed a number of the hieroglyphs to write their own language, using a supposedly new method which is now known by the technical term acrophony. The main weakness of the theory is that it ignores the West Semitic acrophonic syllabary, which already existed, and contained most of the letters of the alphabet. -

Ancient Writing

Ancient Writing As early civilizations developed, societies became more complicated. Record keeping and communication demanded something beyond symbols and pictures to represent the spoken word. This resource explores the early writing systems of four ancient civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Mesoamerica. You'll also learn about the Rosetta Stone, the 19th-century discovery that gave scholars the key that unlocked the language of ancient Egypt. Grade Level: Grades 3-5 Collection: Ancient Art, East Asian Art, Egyptian Art, Pre-Columbian Art Culture/Region: America, China, Egypt Subject Area: History and Social Science, Science, Visual Arts Activity Type: Art in Depth HOW ANCIENT WRITING BEGAN… AND ENDED As early civilizations developed, societies became more complicated. Record keeping and communication demanded something beyond symbols and pictures to represent the spoken word. This gallery explores the early writing systems of four ancient civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Mesoamerica. Here you’ll also learn about the Rosetta Stone, the 19th-century discovery that gave scholars the key that unlocked the language of ancient Egypt. Why were writing systems developed? Communication – Sounds and speech needed to be visually represented. Correspondence – There was a desire to send notes, letters, and instructions. Recording – Bookkeeping tasks became important for counting crops, paying workers’ rations, and collecting taxes. Preservation – Personal stories, rituals, religious texts, hymns, literature, and history all needed to be recorded. Why did some writing systems disappear? Change – Corresponding cultures died out or were absorbed by others. Innovation – Newer, simpler systems replaced older systems. Conquest – Invaders or new rulers imposed their own writing systems. New Beginnings – New ways of writing developed with new belief systems. -

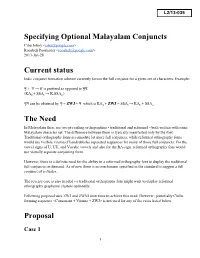

Specifying Optional Malayalam Conjuncts

Specifying Optional Malayalam Conjuncts Cibu Johny <[email protected]> Roozbeh Poornader <[email protected]> 2013Jan28 Current status Indic conjunct formation scheme currently favors the full conjunct for a given set of characters. Example: क् + ष → is prefered as opposed to क् ष. (KAd + SSAl → K.SSAn ) क् ष can be obtained by क् + ZWJ + ष which is KAd + ZWJ + SSAl → KAh + SSAn The Need In Malayalam there are two prevailing orthographies traditional and reformed both written with same Malayalam character set. The difference between them is typically manifested only by the font. Traditional orthography fonts accomodate lot more full conjuncts, while reformed orthography fonts would use visibile virama (Chandrakkala) separated sequences for many of those full conjuncts. For the vowel signs of U, UU, and Vocalic vowels and also for the RAsign, reformed orthography font would use visually separate conjoining form. However, there is a definite need for the ability in a reformed orthography font to display the traditional full conjuncts on demand. As of now there is no mechanism specified in the standard to suggest a full conjunct of a cluster. The reverse case is also needed a traditional orthography font might want to display reformed othrography grapheme clusters optionally. Following proposal uses ZWJ and ZWNJ insertions to achieve this need. However, potentially Chillu forming sequence <Consonant + Virama + ZWJ> is not used for any of the cases listed below. Proposal Case 1 1 The sequence <Consonant + ZWJ + Conjoining Vowel Sign> has following fallback order for display: 1. Full Conjunct 2. Consonant + nonconjoining vowel sign Example with reformed orthography font (in a reformed orthography Malayalam font that can allow optional traditional orthography) SA + Vowel Sign U → SA + ZWJ + Vowel Sign U → Case 2 <Consonant1 + ZWJ + Virama + Consonant2> has following display fallback order: 1. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

Introduction to Old Javanese Language and Literature: a Kawi Prose Anthology

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES THE MICHIGAN SERIES IN SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS Editorial Board Alton L. Becker John K. Musgrave George B. Simmons Thomas R. Trautmann, chm. Ann Arbor, Michigan INTRODUCTION TO OLD JAVANESE LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE: A KAWI PROSE ANTHOLOGY Mary S. Zurbuchen Ann Arbor Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan 1976 The Michigan Series in South and Southeast Asian Languages and Linguistics, 3 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-16235 International Standard Book Number: 0-89148-053-6 Copyright 1976 by Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89148-053-2 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12818-1 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90218-7 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ I made my song a coat Covered with embroideries Out of old mythologies.... "A Coat" W. B. Yeats Languages are more to us than systems of thought transference. They are invisible garments that drape themselves about our spirit and give a predetermined form to all its symbolic expression. When the expression is of unusual significance, we call it literature. "Language and Literature" Edward Sapir Contents Preface IX Pronounciation Guide X Vowel Sandhi xi Illustration of Scripts xii Kawi--an Introduction Language ancf History 1 Language and Its Forms 3 Language and Systems of Meaning 6 The Texts 10 Short Readings 13 Sentences 14 Paragraphs.. -

Maya Hieroglyphic Writing

MAYA HIEROGLYPHIC WRITING Workbook for a Short Course on Maya Hieroglyphic Writing Second Edition, 201 1 J. Kathryn Josserandt and Nicholas A. Hopkins Jaguar Tours 3007 Windy Hill Lane Tallahassee, 32308-4025 FL (850) 385-4344 [email protected] This material is based on work supported in partby Ihe NationalScience Foundation (NSF) under grants BNS-8305806 and BNS-8520749, administered by Ihe Institute for Cultural Ecology of Ihe Tropics (lCEr), and by Ihe National Endowment for Ihe Humanities (NEH), grants RT-20643-86 and RT-21090-89. Any findingsand conclusions or recommendationsexpressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect Ihe views of NSF, NEH, or ICEr. Workbook © Jaguar Tours 2011 CONTENTS Contents Credits and Sources for Figures iv Introductionand Acknowledgements v Bibliography vi Figure 1-1. Mesoamerican Languages x Figure 1-2. The Maya Area xi Figure 1-3. Chronology Chart for tbe Maya Area xii P ART The Classic Maya Maya Hieroglypbic Writing 1: and Figure 14. A FamilyTree of Mayan Languages 2 Mayan Languages 3 Chronology 3 Maya and Earlier Writing 4 Context and Content S Tbe Writing System 5 Figure 1-5. Logographic Signs 6 Figure 1-6. Phonetic Signs 6 Figure 1-7. Landa's "Alphabet" 6 Figure 1-8. A Maya Syllabary 8 Figure 1-9. Reading Order witbin tbe Glyph Block 10 Figure 1-10. Reading Order of Glypb Blocks 10 HieroglyphicTexts II Word Order II Figure 1-11. Examples of Classic Syntax 12 Figure 1-12. Unmarked and Marked Word Order 12 Figure 1-13. Backgrounding and Foregrounding 12-B Figure 1-14. -

Breaking the Maya Code : Michael D. Coe Interview (Night Fire Films)

BREAKING THE MAYA CODE Transcript of filmed interview Complete interview transcripts at www.nightfirefilms.org MICHAEL D. COE Interviewed April 6 and 7, 2005 at his home in New Haven, Connecticut In the 1950s archaeologist Michael Coe was one of the pioneering investigators of the Olmec Civilization. He later made major contributions to Maya epigraphy and iconography. In more recent years he has studied the Khmer civilization of Cambodia. He is the Charles J. MacCurdy Professor of Anthropology, Emeritus at Yale University, and Curator Emeritus of the Anthropology collection of Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. He is the author of Breaking the Maya Code and numerous other books including The Maya Scribe and His World, The Maya and Angkor and the Khmer Civilization. In this interview he discusses: The nature of writing systems The origin of Maya writing The role of writing and scribes in Maya culture The status of Maya writing at the time of the Spanish conquest The impact for good and ill of Bishop Landa The persistence of scribal activity in the books of Chilam Balam and the Caste War Letters Early exploration in the Maya region and early publication of Maya texts The work of Constantine Rafinesque, Stephens and Catherwood, de Bourbourg, Ernst Förstemann, and Alfred Maudslay The Maya Corpus Project Cyrus Thomas Sylvanus Morley and the Carnegie Projects Eric Thompson Hermann Beyer Yuri Knorosov Tania Proskouriakoff His own early involvement with study of the Maya and the Olmec His personal relationship with Yuri -

Beginner's Visual Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs

DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA BEGINNER'S VISUAL CATALOG OF MAYA HIEROGLYPHS Alexandre Tokovinine 2017 INTRODUCTION This catalog of Ancient Maya writing characters is intended as an aid for beginners and intermediate-level students of the script. Most known Ancient Maya inscriptions date to the Late Classic Period (600-800 C.E.), so the characters in the catalog roughly reproduce a generic Late Classic graphic style from the cities in the Southern Lowlands or the area of the present-day department of Petén in Guatemala and the states of Chiapas and Campeche in Mexico. The goal of the catalog is not to demonstrate possible variation in the appearance of individual characters, but to highlight similarities and differences between distinct glyphs. Although all Maya glyphs look like representations of animate and inanimate objects, they are all strictly phonetic: characters called syllabograms encode syllables, whereas other signs known as logograms stand for entire words. The readings of logograms in the catalog are recorded in bold upper case letters and syllabograms with bold lower case letters. Some characters have multiple readings and some readings are less certain than others. This catalog may show several possible readings of a glyph. Uncertain readings are followed by question marks. The sign that looks like a head of a bat, for instance, has two confirmed readings in distinct contexts: a logogram SUUTZ' "bat" and a syllabogram tz'i. The third reading - a syllabogram xu - is plausible, but less well-proven. The corresponding catalog entry will show all these readings underneath the character: SUUTZ'/tz'i/xu? Undeciphered glyphs have also been included in this catalog. -

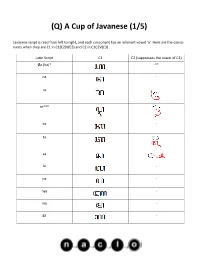

Q) a Cup of Javanese (1/5

(Q) A Cup of Javanese (1/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) Øa (ha)* -** na - ra re*** ka - ta sa la - pa - nya - ma - ga - (Q) A Cup of Javanese (2/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) ba nga - *The consonant is either ‘Ø’ (no consonant) or ‘h,’ but the problem contains only the former. **The ‘-’ means that the form exists, but not in this problem. ***The CV combination ‘re’ (historical remnant of /ɽ/) has its own special letters. ‘ng,’ ‘h,’ and ‘r’ must be C3 in (C1)(C2)VC3 before another C or at the end of a word. All other consonants after V must be C1 of the next syllable. If these consonants end a word, a ‘vowel suppressor’ must be added to suppress the inherent ‘a.’ Latin Script C3 -ng -h -r -C (vowel suppressor) Consonants can be modified to change the inherent vowel ‘a’ in C1(C2)V(C3). Latin Script V* e** (Q) A Cup of Javanese (3/5) Latin Script V* i é u o * If C2 is on the right side of C1, then ‘e,’ ‘i,’ and ‘u’ modify C2.