Culturally Important Objects As Signs of Cretan Protolinear Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ka И @И Ka M Л @Л Ga Н @Н Ga M М @М Nga О @О Ca П

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3319R L2/07-295R 2007-09-11 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, SEI (Universal Scripts Project) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3292 Date: 2007-09-11 1. Introduction. The Javanese script, or aksara Jawa, is used for writing the Javanese language, the native language of one of the peoples of Java, known locally as basa Jawa. It is a descendent of the ancient Brahmi script of India, and so has many similarities with modern scripts of South Asia and Southeast Asia which are also members of that family. The Javanese script is also used for writing Sanskrit, Jawa Kuna (a kind of Sanskritized Javanese), and Kawi, as well as the Sundanese language, also spoken on the island of Java, and the Sasak language, spoken on the island of Lombok. Javanese script was in current use in Java until about 1945; in 1928 Bahasa Indonesia was made the national language of Indonesia and its influence eclipsed that of other languages and their scripts. Traditional Javanese texts are written on palm leaves; books of these bound together are called lontar, a word which derives from ron ‘leaf’ and tal ‘palm’. 2.1. Consonant letters. Consonants have an inherent -a vowel sound. Consonants combine with following consonants in the usual Brahmic fashion: the inherent vowel is “killed” by the PANGKON, and the follow- ing consonant is subjoined or postfixed, often with a change in shape: §£ ndha = § NA + @¿ PANGKON + £ DA-MAHAPRANA; üù n. -

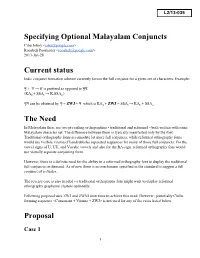

Specifying Optional Malayalam Conjuncts

Specifying Optional Malayalam Conjuncts Cibu Johny <[email protected]> Roozbeh Poornader <[email protected]> 2013Jan28 Current status Indic conjunct formation scheme currently favors the full conjunct for a given set of characters. Example: क् + ष → is prefered as opposed to क् ष. (KAd + SSAl → K.SSAn ) क् ष can be obtained by क् + ZWJ + ष which is KAd + ZWJ + SSAl → KAh + SSAn The Need In Malayalam there are two prevailing orthographies traditional and reformed both written with same Malayalam character set. The difference between them is typically manifested only by the font. Traditional orthography fonts accomodate lot more full conjuncts, while reformed orthography fonts would use visibile virama (Chandrakkala) separated sequences for many of those full conjuncts. For the vowel signs of U, UU, and Vocalic vowels and also for the RAsign, reformed orthography font would use visually separate conjoining form. However, there is a definite need for the ability in a reformed orthography font to display the traditional full conjuncts on demand. As of now there is no mechanism specified in the standard to suggest a full conjunct of a cluster. The reverse case is also needed a traditional orthography font might want to display reformed othrography grapheme clusters optionally. Following proposal uses ZWJ and ZWNJ insertions to achieve this need. However, potentially Chillu forming sequence <Consonant + Virama + ZWJ> is not used for any of the cases listed below. Proposal Case 1 1 The sequence <Consonant + ZWJ + Conjoining Vowel Sign> has following fallback order for display: 1. Full Conjunct 2. Consonant + nonconjoining vowel sign Example with reformed orthography font (in a reformed orthography Malayalam font that can allow optional traditional orthography) SA + Vowel Sign U → SA + ZWJ + Vowel Sign U → Case 2 <Consonant1 + ZWJ + Virama + Consonant2> has following display fallback order: 1. -

Introduction to Old Javanese Language and Literature: a Kawi Prose Anthology

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES THE MICHIGAN SERIES IN SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS Editorial Board Alton L. Becker John K. Musgrave George B. Simmons Thomas R. Trautmann, chm. Ann Arbor, Michigan INTRODUCTION TO OLD JAVANESE LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE: A KAWI PROSE ANTHOLOGY Mary S. Zurbuchen Ann Arbor Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan 1976 The Michigan Series in South and Southeast Asian Languages and Linguistics, 3 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-16235 International Standard Book Number: 0-89148-053-6 Copyright 1976 by Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89148-053-2 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12818-1 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90218-7 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ I made my song a coat Covered with embroideries Out of old mythologies.... "A Coat" W. B. Yeats Languages are more to us than systems of thought transference. They are invisible garments that drape themselves about our spirit and give a predetermined form to all its symbolic expression. When the expression is of unusual significance, we call it literature. "Language and Literature" Edward Sapir Contents Preface IX Pronounciation Guide X Vowel Sandhi xi Illustration of Scripts xii Kawi--an Introduction Language ancf History 1 Language and Its Forms 3 Language and Systems of Meaning 6 The Texts 10 Short Readings 13 Sentences 14 Paragraphs.. -

Beginner's Visual Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs

DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA BEGINNER'S VISUAL CATALOG OF MAYA HIEROGLYPHS Alexandre Tokovinine 2017 INTRODUCTION This catalog of Ancient Maya writing characters is intended as an aid for beginners and intermediate-level students of the script. Most known Ancient Maya inscriptions date to the Late Classic Period (600-800 C.E.), so the characters in the catalog roughly reproduce a generic Late Classic graphic style from the cities in the Southern Lowlands or the area of the present-day department of Petén in Guatemala and the states of Chiapas and Campeche in Mexico. The goal of the catalog is not to demonstrate possible variation in the appearance of individual characters, but to highlight similarities and differences between distinct glyphs. Although all Maya glyphs look like representations of animate and inanimate objects, they are all strictly phonetic: characters called syllabograms encode syllables, whereas other signs known as logograms stand for entire words. The readings of logograms in the catalog are recorded in bold upper case letters and syllabograms with bold lower case letters. Some characters have multiple readings and some readings are less certain than others. This catalog may show several possible readings of a glyph. Uncertain readings are followed by question marks. The sign that looks like a head of a bat, for instance, has two confirmed readings in distinct contexts: a logogram SUUTZ' "bat" and a syllabogram tz'i. The third reading - a syllabogram xu - is plausible, but less well-proven. The corresponding catalog entry will show all these readings underneath the character: SUUTZ'/tz'i/xu? Undeciphered glyphs have also been included in this catalog. -

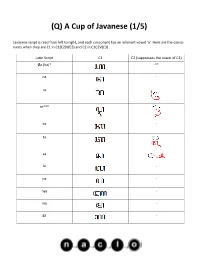

Q) a Cup of Javanese (1/5

(Q) A Cup of Javanese (1/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) Øa (ha)* -** na - ra re*** ka - ta sa la - pa - nya - ma - ga - (Q) A Cup of Javanese (2/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) ba nga - *The consonant is either ‘Ø’ (no consonant) or ‘h,’ but the problem contains only the former. **The ‘-’ means that the form exists, but not in this problem. ***The CV combination ‘re’ (historical remnant of /ɽ/) has its own special letters. ‘ng,’ ‘h,’ and ‘r’ must be C3 in (C1)(C2)VC3 before another C or at the end of a word. All other consonants after V must be C1 of the next syllable. If these consonants end a word, a ‘vowel suppressor’ must be added to suppress the inherent ‘a.’ Latin Script C3 -ng -h -r -C (vowel suppressor) Consonants can be modified to change the inherent vowel ‘a’ in C1(C2)V(C3). Latin Script V* e** (Q) A Cup of Javanese (3/5) Latin Script V* i é u o * If C2 is on the right side of C1, then ‘e,’ ‘i,’ and ‘u’ modify C2. -

Giya Nga Mga Prinsipyo Mahitungod Sa Internal Nga Pagbakwit

GIYA NGA MGA PRINSIPYO MAHITUNGOD SA INTERNAL NGA PAGBAKWIT Pasiunang Pulong Among gihubad sa Cebuano ang dokumentong _Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement,_ nga unang giila sa Tinipong Kanasuran niadtong 1998, tungod kay usa kini ka mahinungdanong lakang sa pagpanalipod ug pag-amping sa katungod sa internal nga mga bakwit sa tibuok kalibutan. Ang katungod nga mapanalipdan batok sa pinugos o tinuyo nga pagpabakwit, sa pagdawat sa makitawhanong hinabang, nga mapanalipdan sa panahon sa pagbakwit ug luwas nga makabalik sa pinuy-anan o makabalhin maoy mga mahinungdanong tawhanong katungod nga angay tahuron aron mapatigbabaw ug mapalambo ang dignidad sa mga bakwit. Sa Pilipinas, ang pagpabakwit ug mga pag-antus nga bunga niini, ingon man ang mga paglapas, kawalay pagpakabana o paghikaw sa mga batakang tawhanong katungod-- sibil, pulitikanhon, ekonomikanhon, sosyal o kultural_sa mga biktima maoy mga rason ngano nga kinahanglang hatagan kini sa dihadihang pagtagad. Kining maong paghubad usa ka hiniusang paningkamot sa Ecumenical Commission for Displaced Families and Communities (ECDFC), sa United Nations Information Center (UNIC) ug sa United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) sa tumong nga maabot ang tanan nga, sa bisan unsang paagi, nalambigit sa mga insidente sa internal nga pagpabakwit (sama sa mga pangulo sa kagamhanan, magbabalaod, mga grupo nga misalmot sa mga armadong panagsangka ug pagsulod sa kayutaan, ug non- government organizations). Hinaut nga kitang tanan makat-on o makapahimulos niining maong dokumento. Isip tubag sa awhag sa UN Commission on Human Rights sa pagpalambo sa usa ka haom nga gambalay sa pagpanalipod ug pagtabang sa mga bakwit sulod sa usa ka nasod, ang Representante sa Kalihim-Heneral sa mga Internal nga mga Bakwit nagmugna niining Giya nga mga Prinsipyo Mahitungod sa Internal nga Pagpabakwit tinambayayongan sa mga batid sa balaod sa kalibutan ug sa pagtambag sa mga ahensya sa Tinipong Kanasuran ug uban pang organisasyon, internasyonal ug rehiyonal, panggobyerno o di-panggobyerno. -

Mga Butang Nga Gikinahanglan Sa Kinabuhi Sa Misyonaryo Pag- Adjust Sa Bag- Ong Mga Kasinatian

Pagpangandam sa Misyonaryo—Leksyon 6 Mga Butang nga Gikinahanglan sa Kinabuhi sa Misyonaryo Gikuha gikan sa Pag- adjust ngadto sa Misyonaryo nga Kinabuhi (booklet nga kapanguhaan, 2013) Sa imong pagsugod og bisan unsa nga bag- ong kasinatian naandan nimo sa una. Ang pagkaon mahimong dili pamilyar. (sama sa pagpamiyembro sa Simbahan o pagtungha sa bag- Naa ka sa gawas nga dili maayo ang panahon ug ma- expose ong eskwelahan), maghinam- hinam ka sa oportunidad—ug sa bag- ong mga kagaw. Ang kabag- o pa lang gani sa sitwas- makulbaan tungod kay wala ka masayud unsay mapaabut. Sa yon makapaluya na. paglabay sa panahon makakat- on ka sa pagbuntog niini nga mga hagit, ug sa ingon ikaw molambo. Emosyonal Mao ra usab kini sa pagmisyon. Usahay ang misyon morag Mahimong mobati ka og kabalaka bahin sa tanan nimong usa ka talagsaon nga espirituhanong panimpalad—o usa ka angayang buhaton, ug mahimong maglisud ka sa pagrelaks. hagit nga mahimo ra nimong masagubang. Sa ubang pana- Mahimong mingawon ka sa balay, mawad- an og paglaum, hon, hinoon, makasugat ka og wala damha nga mga problema malaayan, o mobati og kaguol. Mahimong masinati nimo ang o mga kasinatian nga mas lisud o dili maayo kay sa imong pagsalikway, kasagmuyo, o bisan og kapeligro. Mahimong gilauman. Tingali maghunahuna ka kon unsaon nimo sa pag- mabalaka ka bahin sa pamilya ug mga higala kon wala ka lampus. Ang mga kapanguhaan nga imong gisaligan sa una didto aron motabang nila. nga makatabang nimo sa pagsulbad mahimong wala na. Imbis nga magmadasigon nga mosulay, tingali mahimo ka nang Sosyal mabalak- on, dali nga masuko, kapuyon, o masagmuyo. -

Translation As Commentary in the Sanskrit-Old Javanese Didactic and Religious Literature from Java and Bali Andrea Acri and Thomas M

Translation as Commentary in the Sanskrit-Old Javanese Didactic and Religious Literature from Java and Bali Andrea Acri and Thomas M. Hunter* This article discusses the dynamics of translation and exegesis documented in the body of Sanskrit-Old Javanese Śaiva and Buddhist technical literature of the tutur/tattva genre, composed in Java and Bali in the period from c. the ninth to the sixteenth century. The texts belonging to this genre, mainly preserved on palm-leaf manuscripts from Bali, are concerned with the reconfiguration of Indic metaphysics, philosophy, and soteriology along localized lines. Here we focus on the texts that are built in the form of Sanskrit verses provided with Old Javanese prose exegesis – each unit forming a »translation dyad«. The Old Javanese prose parts document cases of linguistic and cultural »localization« that could be regarded as broadly corresponding to the Western categories of translation, paraphrase, and commen- tary, but which often do not fit neatly into any one category. Having introduced the »vyākhyā-style« form of commentary through examples drawn from the early inscriptional and didactic literature in Old Javanese, we present key instances of »cultural translations« as attested in texts composed at different times and in different geo- graphical and religio-cultural milieus, and describe their formal features. Our aim is to do- cument how local agents (re-)interpreted, fractured, and restated the messages conveyed by the Sanskrit verses in the light of their contingent contexts, agendas, and prevalent exegeti- cal practices. Our hypothesis is that local milieus of textual production underwent a pro- gressive »drift« from the Indic-derived scholastic traditions that inspired – and entered into a conversation with – the earliest sources, composed in Central Java in the early medieval period, and progressively shifted towards a more embedded mode of production in East Java and Bali from the eleventh to the sixteenth century and beyond. -

Information, Characters, Unicode

Information, Characters, Unicode Unicode © 24 August 2021 1 / 107 Hidden Moral Small mistakes can be catastrophic! Style Care about every character of your program. Tip: printf Care about every character in the program’s output. (Be reasonably tolerant and defensive about the input. “Fail early” and clearly.) Unicode © 24 August 2021 2 / 107 Imperative Thou shalt care about every Ěaracter in your program. Unicode © 24 August 2021 3 / 107 Imperative Thou shalt know every Ěaracter in the input. Thou shalt care about every Ěaracter in your output. Unicode © 24 August 2021 4 / 107 Information – Characters In modern computing, natural-language text is very important information. (“number-crunching” is less important.) Characters of text are represented in several different ways and a known character encoding is necessary to exchange text information. For many years an important encoding standard for characters has been US ASCII–a 7-bit encoding. Since 7 does not divide 32, the ubiquitous word size of computers, 8-bit encodings are more common. Very common is ISO 8859-1 aka “Latin-1,” and other 8-bit encodings of characters sets for languages other than English. Currently, a very large multi-lingual character repertoire known as Unicode is gaining importance. Unicode © 24 August 2021 5 / 107 US ASCII (7-bit), or bottom half of Latin1 NUL SOH STX ETX EOT ENQ ACK BEL BS HT LF VT FF CR SS SI DLE DC1 DC2 DC3 DC4 NAK SYN ETP CAN EM SUB ESC FS GS RS US !"#$%&’()*+,-./ 0123456789:;<=>? @ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO PQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_ `abcdefghijklmno pqrstuvwxyz{|}~ DEL Unicode Character Sets © 24 August 2021 6 / 107 Control Characters Notice that the first twos rows are filled with so-called control characters. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 3.0, Issued by the Unicode Consor- Tium and Published by Addison-Wesley

The Unicode Standard Version 3.0 The Unicode Consortium ADDISON–WESLEY An Imprint of Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Reading, Massachusetts · Harlow, England · Menlo Park, California Berkeley, California · Don Mills, Ontario · Sydney Bonn · Amsterdam · Tokyo · Mexico City Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. If these files have been purchased on computer-readable media, the sole remedy for any claim will be exchange of defective media within ninety days of receipt. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. ISBN 0-201-61633-5 Copyright © 1991-2000 by Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise, without the prior written permission of the publisher or Unicode, Inc. -

P. Carey Javanese Histories of Dipanagara: the Buku Kedhun Kebo, Its Authorship and Historical Importance

P. Carey Javanese histories of Dipanagara: the Buku Kedhun Kebo, its authorship and historical importance In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 130 (1974), no: 2/3, Leiden, 259-288 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 05:56:49PM via free access P. B. R. CAREY JAVANESE HISTORIES OF DIPANAGARA: THE BUKU KEDHU1NJ KËBO, ITS AUTHORSHIP AND HISTORICAL IMPORTANCE a. Introduction The historian who wishes to make a study of the Java War (1825-1830) and its antecedents is faced with an unusually rich collection of Javanese historical materials on which to draw. These materials include both original letters and Babads (Javanese historical chronicles) written by participants in the events, but of these the Babad accounts are by far the most important. These Javanese histories are usually classified under the loose title of 'Babad Dipanagara' in library catalogues, although they often deal with very different facets of Parjeran Dipanagara's struggle against the Dutch, and are sometimes even written by men who took part on opposing sides during the war. Most of the original 'Babad Dipanagara'. and their MS. copies are kept in public collections in the Netherlands and in Indonesia, although there are still a few in private family collections. The most important public collections are those of the Leiden University Library (The Netherlands), the Museum Pusat (Jakarta), the Kraton (court) Libraries of Surakarta and Yogyakarta (Central Java), and the Library of the Sana Budaya Museum (Yogyakarta).1 The absence of any comprehensive survey of this Babad material which could give a guide as to the location of the original MSS., their dates and background, makes the task of the historian exceedingly difficult. -

Tanan Ini Ginhimo Ko Para Sa Imo Nagkari Ako

TANAN INI GINHIMO KO PARA SA IMO NAGKARI AKO... bangud sa “imo” sala. “Kay nasulat na, wala sing matarung..., wala bisan isa.” (Taga Roma 3:10) “Sanglit ang tanan nagpakasala kag nawad-an sang himaya sang Dios;” (Taga Roma 3:23) “Matu-od ang pinamolong kag takus sang bug-os nga pagbaton, nga si Kristo Jesus nag-abot sa kalibutan sa pagluwas sang mga makasasala;” (1 Timoteo 1:15a) NAPATAY AKO... sa pagbayad sang “imo” sala. “Apang sia ginpilas tungud sang aton mga paglalis, ginhanog sia tungud sa aton mga kalautan: ang silot sang aton paghidait yara sa iya, kag sa iya mga labud ginaayo kita.” (Isaias 53:5) “Apang ang Dios nagpakilala sang iya kaugalingon nga gugma sa aton nga sang makasasala pa kita si Kristo napatay tungod sa aton. Busa sanglit karon ginpakama- tarung kita paagi sa iya dugo, labi pa nga maluwas kita sa kasingkal sang Dios paagi sa iya. (Mga Taga Roma 5:8-9) ”Nga sa iya gintubos kita paagi sa kapatawaran sang aton mga sala:” (Colosas 1:14) GINBANHAW AKO... sa pagluwas sa “imo” sa walay katubtuban. “Gani sarang sia sa tanan nga tion sa pagluwas sa ila nga nagapalapit sa Dios paagi sa iya, sanglit nagakabuhi sila gihapon sa pagpatunga nga nagatabang sa ila.” (Hebreo 7:25) “Ang mga karnero nagapamati sang akon tingug kag nakilala ko sia kag nagasunod sila sa akon, kag nagahatag ako sa ila sing kabuhi nga walay katapusan, kag indi na gid sila mawala, kag walay isa nga makaa- gaw sa ila sa akon kamut.” (Juan 10:27-28) “Kag ang panaksi amo ini, nga ang Dios naghatag sa aton sing kabuhi nga walay katapusan, kag ining kabuhi yara sa iya anak.” (1 Juan 5:11) DAPAT IKAW MAGHINULSOL..