Request for Project Funding from the Adaptation Fund

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Ground up Case Studies in Community Empowerment

REBUILDING BROKEN LIVES After gaining Independence in 1991, Tajikistan endured economic collapse, civil war, and widespread hunger. To help rural people back on their feet, ADB financed a pilot microcredit-based livelihood project for women and farmers. Implemented through two international NGOs, the Aga Khan Foundation and CARE International, the experiment encountered many challenges, but produced several positive outcomes The women’s group composes a peaceful scene, without a hint of the tumultuous circumstances that spawned it. In a drab building in Vahdat district in western Tajikistan, a dozen women, mostly young, are bent over a long table, their fingers busy with embroidery. Along a wall behind them, older women are stitching a floral- patterned kurpacha, the thick, multipurpose Tajik quilt. Some of the girls are teenagers, who are only dimly aware of the horrors that followed Tajikistan’s unsought independence in 1991. But Zebo Oimatova, 52, a benevolent figure in traditional kurta (robe) and headscarf who is watching over the room like a mother hen, remembers it all—economic ruin, villages torn apart by civil war, the hardscrabble existence and, finally, a chance to rebuild shattered lives. In 2002, Ms. Oimatova, a warm-hearted woman of simple sincerity, was elected chairperson of a women’s federation, a community-based organization created under a pilot Asian Development Bank (ADB)-financed project to provide microcredit for women to start small businesses and farmers to improve crops. Despite being overawed—“I thought I could not manage the job because I am only average and not so well educated,” she confesses—Ms. Oimatova has seen her group grow from a handful to over 2,500 members and, importantly, become self-sufficient. -

BISHKEK to TBILISI (42 Days) Kyrgyzstan to Caucasus

BISHKEK to TBILISI (42 days) Kyrgyzstan to Caucasus COUNTRIES VISITED: ARMENIA, AZERBAIJAN, GEORGIA, KYRGYZSTAN, TAJIKISTAN, TURKMENISTAN, UZBEKISTAN INCLUDES • Accommodation - approx. 45% camping & 55% simple hostels/hotels • Turkmenistan Letter of Invitation support and fees • Darvaza Gas Crater • Ashgabat city tour • 4X4 Desert Safari in Turkmenistan • Caspian Ferry • Meals - approx. 50% • All Transport on Oasis Expedition Truck • Camping and Cooking equipment • Services of Oasis Crew EXCLUDES • Visas • Optional Excursions as listed in the Pre-Departure Information www.oasisoverland.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)203 725 8924 • Flights • Airport Taxes & Transfers • Travel Insurance • Meals - approx. 50% • Drinks • Tips TRIP ITINERARY DAYS 1 - 5 BISHKEK TO FANN MOUNTAINS We leave Bishkek and drive through stunning mountain views and past the turquoise waters of Toktogul Reservoir, before arriving in Osh. Osh, the second biggest and the country’s oldest, city. Make sure you visit the bazaar, which has occupied the same spot for over 2000 years and used to be a major stop along the ancient Silk Road. We enter Uzbekistan and arrive in the Fergana Valley, known for its silk production and the area that gave the name to one of the greatest routes in history. Continuing west we arrive in to Khujand – although today the city is not one of the most picturesque, it has had an important role in the history of the Silk Road and was one of the furthest points reached by Alexander the Great. It is said in this area that he wept, saying he had no further territory to conquer. We have time to visit the Fortress and Panjshanbe Market (one of the largest covered markets in Central Asia). -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: TAJIKISTAN January 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Tajikistan (Jumhurii Tojikiston). Short Form: Tajikistan. Term for Citizen(s): Tajikistani(s). Capital: Dushanbe. Other Major Cities: Istravshan, Khujand, Kulob, and Qurghonteppa. Independence: The official date of independence is September 9, 1991, the date on which Tajikistan withdrew from the Soviet Union. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), International Women’s Day (March 8), Navruz (Persian New Year, March 20, 21, or 22), International Labor Day (May 1), Victory Day (May 9), Independence Day (September 9), Constitution Day (November 6), and National Reconciliation Day (November 9). Flag: The flag features three horizontal stripes: a wide middle white stripe with narrower red (top) and green stripes. Centered in the white stripe is a golden crown topped by seven gold, five-pointed stars. The red is taken from the flag of the Soviet Union; the green represents agriculture and the white, cotton. The crown and stars represent the Click to Enlarge Image country’s sovereignty and the friendship of nationalities. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Iranian peoples such as the Soghdians and the Bactrians are the ethnic forbears of the modern Tajiks. They have inhabited parts of Central Asia for at least 2,500 years, assimilating with Turkic and Mongol groups. Between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., present-day Tajikistan was part of the Persian Achaemenian Empire, which was conquered by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. After that conquest, Tajikistan was part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state to Alexander’s empire. -

Long-Term Hydro–Climatic Trends in the Mountainous Kofarnihon River Basin in Central Asia

water Article Long-Term Hydro–Climatic Trends in the Mountainous Kofarnihon River Basin in Central Asia Aminjon Gulakhmadov 1,2,3,4 , Xi Chen 1,2,*, Nekruz Gulahmadov 2,4,5 , Tie Liu 2 , Rashid Davlyatov 4,6, Safarkhon Sharofiddinov 4,6 and Manuchekhr Gulakhmadov 1,5,6 1 Research Center of Ecology and Environment in Central Asia, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (M.G.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China; [email protected] (N.G.); [email protected] (T.L.) 3 Ministry of Energy and Water Resources of the Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe 734064, Tajikistan 4 Institute of Water Problems, Hydropower and Ecology of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe 734042, Tajikistan; [email protected] (R.D.); [email protected] (S.S.) 5 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 6 Committee for Environmental Protection under the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe 734034, Tajikistan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-991-782-3131 Received: 11 June 2020; Accepted: 25 July 2020; Published: 29 July 2020 Abstract: Hydro–climatic variables play an essential role in assessing the long-term changes in streamflow in the snow-fed and glacier-fed rivers that are extremely vulnerable to climatic variations in the alpine mountainous regions. The trend and magnitudinal changes of hydro–climatic variables, such as temperature, precipitation, and streamflow, were determined by applying the non-parametric Mann–Kendall, modified Mann–Kendall, and Sen’s slope tests in the Kofarnihon River Basin in Central Asia. -

An Excursion-Historical Tour Passes Along the Territory of Two Modern Countries: Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. It Repeats the Part

An excursion-historical tour passes along the territory of two modern countries: Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. It repeats the part of the way of Alexander’s Asian campaign. Using bulls’ skins, Alexander’s army had crossed Amudarya river and invaded the territory of Sogdiana (an interfluve of Amudarya and Sirdarya). It took three years for the forces of Alexander to conquest this region and suppress the often aroused rebellions. Here he had married a beautiful woman Roxana (the daughter of a local lord). Here, in mountain regions, for siege of the fortresses Alexander (first time in the world) had successfully practiced mountainous special troops. During his campaign he founded many settlements, including big towns. One of them is Alexandria Eshata (Distant) – a modern Khodjent. The tour is assigned for those who love history, ethnography and oriental exotic. The itinerary: Tashkent – Samarkand – Bukhara – Shakhrisabz – Termez – Baysun – Dushanbe – Margib – Iskanderkul lake – Istravshan – Khujand – Tashkent Duration: 15 days Number of tourists in the group: min. – 1 pax, max. – 16 pax Language: English PROGRAM OF THE TOUR Day 1 Arrival to Tashkent. Transfer to hotel. Rest. Day 2 After breakfast drive to Samarkand (300 km, 5 hrs). On arrival check in hotel & short rest. Afternoon sightseeing: Registan Square - the "heart" of Samarkand - ensemble of 3 majestic medreses (XIV-XVI c.c.) – Sherdor, Ulugbek and Tillya Qory, the grandiose cathedral Bibi-Khanum Mosque (XV c.), Gur-Emir Mausoleum (XV c.). Day 3 After breakfast continue of sightseeing in Samarkand: Tamerlan’s grandson Ulugbek’s the well-known ruler and astronomer-scientist observatory (1420) - the ruins of an immense (30 m) astrolabe for observing stars position, Shakhi- Zinda Necropolis (XI-XVIII cc), exotic Siab bazaar. -

TAJIKISTAN TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock

APPENDIX 15 TAJIKISTAN 870 км TAJIKISTAN 414 км Sangimurod Murvatulloev 1161 км Dushanbe,Tajikistan / [email protected] Tel: (992 93) 570 07 11 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) 1206 км Shiraz, Islamic Republic of Iran 3 651 . 9 - 13 November 2008 Общая протяженность границы км Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock - 2007 Territory - 143.000 square km Cities Dushanbe – 600.000 Small Population – 7 mln. Khujand – 370.000 Capital – Dushanbe Province Cattle Dairy Cattle ruminants Yak Kurgantube – 260.000 Official language - tajiki Kulob – 150.000 Total in Ethnic groups Tajik – 75% Tajikistan 1422614 756615 3172611 15131 Uzbek – 20% Russian – 3% Others – 2% GBAO 93619 33069 267112 14261 Sughd 388486 210970 980853 586 Khatlon 573472 314592 1247475 0 DRD 367037 197984 677171 0 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) Country – Livestock - 2007 Current FMD Situation and Trends Density of sheep and goats Prevalence of FM D population in Tajikistan Quantity of beans Mastchoh Asht 12827 - 21928 12 - 30 Ghafurov 21929 - 35698 31 - 46 Spitamen Zafarobod Konibodom 35699 - 54647 Spitamen Isfara M astchoh A sht 47 -

Tourism in Tajikistan As Seen by Tour Operators Acknowledgments

Tourism in as Seen by Tour Operators Public Disclosure Authorized Tajikistan Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized DISCLAIMER CONTENTS This work is a product of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS......................................................................i The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other INTRODUCTION....................................................................................2 information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. TOURISM TRENDS IN TAJIKISTAN............................................................5 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS TOURISM SERVICES IN TAJIKISTAN.......................................................27 © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank TOURISM IN KHATLON REGION AND 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: +1 (202) 522-2422; email: [email protected]. GORNO-BADAKHSHAN AUTONOMOUS OBLAST (GBAO)...................45 The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and li- censes, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, PROFILE AND LIST OF RESPONDENTS................................................57 Cover page images: 1. Hulbuk Fortress, near Kulob, Khatlon Region 2. Tajik girl holding symbol of Navruz Holiday 3. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

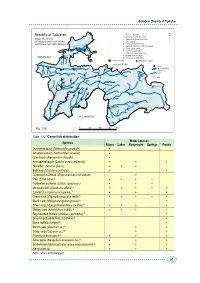

Biological Diversity of Tajikistan Republic of Tajikistan The Legend: 1 - Acipenser nudiventris Lovet 2 - Salmo trutta morfa fario Linne ya 3 - A.a.a. (Linne) ar rd Sy 4 - Ctenopharyngodon idella Kayrakkum reservoir 5 - Hypophthalmichtus molitrix (Valenea) Khujand 6 - Silurus glanis Linne 7 - Cyprinus carpio Linne a r a 8 - Lucioperca lucioperea Linne f s Dagano-Say I 9 - Abramis brama (Linne) reservoir UZBEKISTAN 10 -Carassus auratus gibilio Katasay reservoir economical pond distribution location KYRGYZSTAN cities Zeravshan lakes and water reservoirs Yagnob rivers Muksu ob Iskanderkul Lake Surkh o CHINA b r Karakul Lake o S b gou o in h l z ik r b e a O b V y u k Dushanbe o ir K Rangul Lake o rv Shorkul Lake e P ch z a n e n a r j V ek em Nur gul Murg u az ab s Y h k a Y u ng Sarez Lake s l ta i r a u iz s B ir K Kulyab o T Kurgan-Tube n a g i n r Gunt i Yashilkul Lake f h a s K h Khorog k a Zorkul Lake V Turumtaikul Lake ra P a an d j kh Sha A AFGHANISTAN m u da rya nj a P Fig. 1.16. 0 50 100 150 Km Table 1.12. Game fish distribution Water sources Species Rivers Lakes Reservoirs Springs Ponds Dushanbe loach (Nemachilus pardalis) + Amudarya loach (Nemachilus oxianus) + Gray loach (Nemachilus dorsalis) + Aral spined loach (Cobitis aurata aralensis) + + + Sheatfish (Sclurus glanis) + + + Bullhead (Ictalurus punctata) А + + Turkestan bullhead (Glyptosternum reticulatum) + Pike (Esox lucius) + + + + Turkestan bullhead (Cottus spinolosus) + + + Mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis) А + + + + + Zander (Lucioperca lucioperea) А + + + Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon della) А + + + + + Black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) А + Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthus molitrix) А + + + + Motley carp (Aristichthus nobilis) А + + + + Big-mouthed buffalo (Ictiobus cyprinellus) А + Small-mouthed buffalo (I.bufalus) А + Black buffalo (I.niger) А + Mirror carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Scaly carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Pseudorasbora parva А + + + Amur goby (Neogobius amurensis sp.) А + + + Snakehead (Ophiocephalus argus warpachowski) А + + + Hemiculter sp. -

In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great and Discover the Fabled Silk Road Oasis Towns of with Another Traveller of the Same Gender and Tashkent, Samarkand and Bukhara

in the footsteps of Central Asia Central alexander the great trip highligh ts Discover the desert city of Bukhara Take in the fabled Silk Road city of Samarkand Hike around the picturesque lake of the Fann mountains, Lake Iskander‑Kul Marvel at splendid markets, minarets and medressa Experience the historic centre of Shakhrisabz Journey to the ancient city of Khujand Trip Duration 15 days Trip Code: IFA Grade Introductory Activities Adventure Touring Summary 15 day trip, 12 nights hotel, 2 nights homestay welcome to why travel with World Expeditions? When planning travel to a remote destination, many factors need to be World Expeditions considered. Our extra attention to detail and seamless operations on the Thank you for your interest in our In the Footsteps of Alexander the ground ensure that you will have a memorable experience. Every trip is Great trip. At World Expeditions we are passionate about our off the accompanied by an experienced local leader, as well as support staff that beaten track experiences as they provide our travellers with the thrill share a passion for the region, and a desire to share it with you. We take of coming face to face with untouched cultures as well as wilderness every precaution to ensure smooth logistics. In most cases, all internal regions of great natural beauty. We are committed to ensuring that transport, entrance fees, national park fees and transfers are included our unique itineraries are well researched, affordable and tailored in the cost of your trip. Most importantly, our adventures always aim to for the enjoyment of small groups or individuals ‑ philosophies that benefit the local people we interact with, safeguard the ecosystems we have been at our core since 1975 when we began operating adventure explore and contribute to the sustainability of travel in the regions we holidays. -

1 Paradise Lost: Tajik Representations of Afghan

Paradise Lost: Tajik Representations of Afghan Badakhshan ABSTRACT In 2003 a Tajik film crew was permitted to cross the tightly controlled border into Afghan Badakhshan in order to film scenes for a commemorative documentary Sacred Traditions in Sacred Places. Although official state policies and international non- governmental organizations’ discourses concerning the Tajik-Afghan border have increasingly stressed freer movement and greater connectivity between the two sides, this strongly contrasts with the lived experience of Tajik Badakhshanis. The film crew was struck by the great disparity in the daily lives and lifeways of Ismaili Muslims on either side of this border, but also the depth of their shared past and present. This paper explores at times contradictory narratives of nostalgia and longing recounted by the film crew through the documentary film itself and in interviews with the film crew during film production and screening. I claim that emotions like nostalgia and longing are an affective response and resource serving to help Tajik Badakhshanis understand and manage daily life in a highly regulated border zone. INTRODUCTION In a darkened editing room in Dom Kino (‘film house’) in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, we watch footage of sweeping vistas of northern Afghanistan, close-ups of rushing mountain streams, and landscapes dotted with shepherds herding flocks across high pasture. The film’s research coordinator is seated next to me, and every few moments she sighs. She is struggling to decide which of these images will end up on the cutting room floor. “I was in paradise at that time,” she says, “I was in paradise at that moment….” In far southeastern Tajikistan the border with Afghanistan is the Panj River, in some places wide and rushing and in other places shallow and calm enough for a person to wade across. -

"A New Stage of the Afghan Crisis and Tajikistan's Security"

VALDAI DISCUSSION CLUB REPORT www.valdaiclub.com A NEW STAGE OF THE AFGHAN CRISIS AND TAJIKISTAN’S SECURITY Akbarsho Iskandarov, Kosimsho Iskandarov, Ivan Safranchuk MOSCOW, AUGUST 2016 Authors Akbarsho Iskandarov Doctor of Political Science, Deputy Chairman of the Supreme Soviet, Acting President of the Republic of Tajikistan (1990–1992); Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Republic of Tajikistan; Chief Research Fellow of A. Bahovaddinov Institute of Philosophy, Political Science and Law of the Academy of Science of the Republic of Tajikistan Kosimsho Iskandarov Doctor of Historical Science; Head of the Department of Iran and Afghanistan of the Rudaki Institute of Language, Literature, Oriental and Written Heritage of the Academy of Science of the Republic of Tajikistan Ivan Safranchuk PhD in Political Science; associate professor of the Department of Global Political Processes of the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO-University) of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia; member of the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy The views and opinions expressed in this Report are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise. Contents The growth of instability in northern Afghanistan and its causes ....................................................................3 Anti-government elements (AGE) in Afghan provinces bordering on Tajikistan .............................................5 Threats to Central Asian countries ........................................................................................................................7 Tajikistan’s approaches to defending itself from threats in the Afghan sector ........................................... 10 A NEW STAGE OF THE AFGHAN CRISIS AND TAJIKISTAN’S SECURITY The general situation in Afghanistan after two weeks of fierce fighting and not has been deteriorating during the last few before AGE carried out an orderly retreat. -

CBD First National Report

REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FIRST NATIONAL REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION Dushanbe – 2003 1 REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FIRST NATIONAL REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION Dushanbe – 2003 3 ББК 28+28.0+45.2+41.2+40.0 Н-35 УДК 502:338:502.171(575.3) NBBC GEF First National Report on Biodiversity Conservation was elaborated by National Biodiversity and Biosafety Center (NBBC) under the guidance of CBD National Focal Point Dr. N.Safarov within the project “Tajikistan Biodiversity Strategic Action Plan”, with financial support of Global Environmental Facility (GEF) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Copyright 2003 All rights reserved 4 Author: Dr. Neimatullo Safarov, CBD National Focal Point, Head of National Biodiversity and Biosafety Center With participation of: Dr. of Agricultural Science, Scientific Productive Enterprise «Bogparvar» of Tajik Akhmedov T. Academy of Agricultural Science Ashurov A. Dr. of Biology, Institute of Botany Academy of Science Asrorov I. Dr. of Economy, professor, Institute of Economy Academy of Science Bardashev I. Dr. of Geology, Institute of Geology Academy of Science Boboradjabov B. Dr. of Biology, Tajik State Pedagogical University Dustov S. Dr. of Biology, State Ecological Inspectorate of the Ministry for Nature Protection Dr. of Biology, professor, Institute of Plants Physiology and Genetics Academy Ergashev А. of Science Dr. of Biology, corresponding member of Academy of Science, professor, Institute Gafurov A. of Zoology and Parasitology Academy of Science Gulmakhmadov D. State Land Use Committee of the Republic of Tajikistan Dr. of Biology, Tajik Research Institute of Cattle-Breeding of the Tajik Academy Irgashev T. of Agricultural Science Ismailov M. Dr. of Biology, corresponding member of Academy of Science, professor Khairullaev R.