World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Ground up Case Studies in Community Empowerment

REBUILDING BROKEN LIVES After gaining Independence in 1991, Tajikistan endured economic collapse, civil war, and widespread hunger. To help rural people back on their feet, ADB financed a pilot microcredit-based livelihood project for women and farmers. Implemented through two international NGOs, the Aga Khan Foundation and CARE International, the experiment encountered many challenges, but produced several positive outcomes The women’s group composes a peaceful scene, without a hint of the tumultuous circumstances that spawned it. In a drab building in Vahdat district in western Tajikistan, a dozen women, mostly young, are bent over a long table, their fingers busy with embroidery. Along a wall behind them, older women are stitching a floral- patterned kurpacha, the thick, multipurpose Tajik quilt. Some of the girls are teenagers, who are only dimly aware of the horrors that followed Tajikistan’s unsought independence in 1991. But Zebo Oimatova, 52, a benevolent figure in traditional kurta (robe) and headscarf who is watching over the room like a mother hen, remembers it all—economic ruin, villages torn apart by civil war, the hardscrabble existence and, finally, a chance to rebuild shattered lives. In 2002, Ms. Oimatova, a warm-hearted woman of simple sincerity, was elected chairperson of a women’s federation, a community-based organization created under a pilot Asian Development Bank (ADB)-financed project to provide microcredit for women to start small businesses and farmers to improve crops. Despite being overawed—“I thought I could not manage the job because I am only average and not so well educated,” she confesses—Ms. Oimatova has seen her group grow from a handful to over 2,500 members and, importantly, become self-sufficient. -

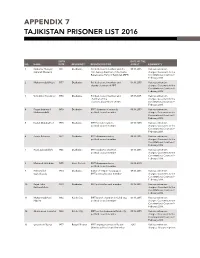

Appendix 7 Tajikistan Prisoner List 2016

APPENDIX 7 TAJIKISTAN PRISONER LIST 2016 BIRTH DATE OF THE NO. NAME DATE RESIDENCY RESPONSIBILITIES ARREST COMMENTS 1 Saidumar Huseyini 1961 Dushanbe Political council member and the 09.16.2015 Various extremism (Umarali Khusaini) first deputy chairman of the Islamic charges. Case went to the Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 2 Muhammadalii Hayit 1957 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.16.2015 Various extremism deputy chairman of IRPT charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 3 Vohidkhon Kosidinov 1956 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.17.2015 Various extremism chairman of the charges. Case went to the elections department of IRPT Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 4 Fayzmuhammad 1959 Dushanbe IRPT chairman of research, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Muhammadalii political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 5 Davlat Abdukahhori 1975 Dushanbe IRPT foreign relations, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 6 Zarafo Rahmoni 1972 Dushanbe IRPT chairman advisor, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 7 Rozik Zubaydullohi 1946 Dushanbe IRPT academic chairman, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 8 Mahmud Jaloliddini 1955 Hisor District IRPT chairman advisor, 02.10.2015 political council member 9 Hikmatulloh 1950 Dushanbe Editor of “Najot” newspaper, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Sayfullozoda IRPT political council member charges. -

Formative Research on Infant and Young Child Feeding

FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING Final Report AND MATERNAL NUTRITION 2016 IN TAJIKISTAN Conducted by Dornsife School of Public Health & College of Nursing and Health Professions, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA USA For UNICEF Tajikistan Under Drexel’s Long Term Agreement for Services In Communication for Development (C4D) with UNICEF And Contract # 43192550 January 11 through November 30, 2016 Principal Investigator Ann C Klassen, PhD , Professor, Department of Community Health and Prevention Co-Investigators Brandy Joe Milliron PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences Beth Leonberg, MA, MS, RD – Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences Graduate Research Staff Lisa Bossert, MPH, Margaret Chenault, MS, Suzanne Grossman, MSc, Jalal Maqsood, MD Professional Translation Staff Rauf Abduzhalilov, Shokhin Asadov, Malika Iskandari, Muhiddin Tojiev This research is conducted with the financial support of the Government of the Russian Federation Appendices : (Available Separately) Additional Bibliography Data Collector Training, Dushanbe, March, 2016 Data Collection Instruments Drexel Presentations at National Nutrition Forum, Dushanbe, July, 2016 cover page photo © mromanyuk/2014 FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Executive Summary 5 Section 2: Overview of Project 12 Section 3: Review of the Literature 65 Section 4: Field Work Report 75 Section 4a: Methods 86 Section 4b: Results 101 Section 5: Conclusions and Recommendations 120 Section 6: Literature Cited 138 FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING 3 AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN SECTION 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Tajikistan is a mountainous, primarily rural country of approximately 8 million residents in Central Asia. -

Tajikistan TAJ1 Project Name: Railway Kolkhozabad

Tajikistan TAJ1 Project Name: Railway Kolkhozabad - Dusti - Nizhniy Panj - Kunduz (IGA) Location: The beginning of the route is in the settlement Kolkhozabad district of Khatlon region on the existing railway station Kurgan-Tube - Termez, the end of the route - the boundary of the Republic of Tajikistan to the Islamic State of Afghanistan and then to the town of Kunduz Brief Description: • Start the proposed railway line Kolkhozabad - Dusti - Nizhniy Panj - Kunduz (IGA), located 5 km south-west of the railway station Kolkhozabad on the existing railway station Kurgan- Tube - Termez and then laid in a southerly direction, crossing the channel Jilikul at 1 and 2 km passes along the main canal Yakkadin and goes to the village. Dusti in the south-easterly direction at 30 kilometres. In this segment of the railway route intersects 5 roads of local importance. Going round the village. Dusti from the south, the route of the railway runs parallel with the 32 km highway of Kurgan-Tube - Dusti - Nizhniy Panj, crossing it at Km 39 +500, rising to 45 kilometres Karadumskomu array and then descends to the right bank. Panj. • Near the newly built and put into operation in Afghanistan road bridge across the River Panj proposed to construct a new railway bridge 700 meters long scheme 16,5 m +6 h110m 16.5 m. The length of new railway line on a plot Kolkhozabad-Dusti - Nizhniy Panj be 50 km and 65 km further on the territory of the Islamic State of Afghanistan to the town of Kunduz. To ensure the cargo and passenger traffic in the village. -

Prevalence and Risk Factors for Brucella Seropositivity Among Sheep and Goats in a Peri-Urban Region of Tajikistan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Trop Anim Health Prod (2016) 48:553–558 DOI 10.1007/s11250-015-0992-3 REGULAR ARTICLES Prevalence and risk factors for Brucella seropositivity among sheep and goats in a peri-urban region of Tajikistan Elisabeth Lindahl Rajala1 & Cecilia Grahn 1 & Isabel Ljung1 & Nosirjon Sattorov2 & Sofia Boqvist 3 & Ulf Magnusson1 Received: 15 October 2015 /Accepted: 28 December 2015 /Published online: 15 January 2016 # The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This cross-sectional study aimed to estimate the 1.2–1.6). These results indicate high prevalence of Brucella seroprevalence of Brucella infection among sheep and goats infection among sheep and goats in the peri-urban area of the on small-scale farms in a peri-urban area of Tajikistan and capital city in Tajikistan. Given the dense human population in identify factors associated with seropositivity. The study pop- such areas, this could constitute a threat to public health, be- ulation was 667 female sheep and goats >6 months of age sides causing significant production losses. from 21 villages in four districts surrounding the capital city, Dushanbe. Individual blood samples were collected during Keywords Brucellosis .Tajikistan .Smallruminants .ELISA October and November 2012 and analysed with indirect en- zyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Positive samples were confirmed with competitive ELISA. To identify factors Introduction associated with seropositivity at an individual level, a gener- alised linear mixed model was applied to account for cluster- Brucellosis is one of the most common and economically ing of individuals within villages and districts. -

Compendium of Central Asian Military and Security Activity

WL KNO EDGE NCE ISM SA ER IS E A TE N K N O K C E N N T N I S E S J E N A 3 V H A A N H Z И O E P W O I T E D N E Z I A M I C O N O C C I O T N S H O E L C A I N M Z E N O T Compendium of Central Asian Military and Security Activity MATTHEW STEIN Open Source, Foreign Perspective, Underconsidered/Understudied Topics The Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is an open source research organization of the U.S. Army. It was founded in 1986 as an innovative program that brought together military specialists and civilian academics to focus on military and security topics derived from unclassified, foreign media. Today FMSO maintains this research tradition of special insight and highly collaborative work by conducting unclassified research on foreign perspectives of defense and security issues that are understudied or unconsidered. Author Background Matthew Stein is an analyst at the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. His specific research expertise includes “Joint military exercises involving Central Asian militaries and security forces,” “Incidents of violence and civil unrest in Central Asia,” “Extremist and Terrorist Groups in Central Asia,” and “Border issues in Central Asia.” He has conducted briefings and participated in training events for units deploying to the Central Asia region and seminars for senior U.S. Army leaders. He has an M.A. -

Monitoring & Early Warning in Tajikistan

Tajikistan Monitoring & Early Warning Monthly Report Monitoring & Early Warning in Tajikistan MONTHLY REPORT APRIL 2012 1 Tajikistan Monitoring & Early Warning Report – April 2012 GENERAL TRENDS NATURAL HAZARDS During April, avalanches, mudflows and floods can be expected. Floods can be triggered by rain on snow and mudflows triggered by locally heavy precipitation or rapid snow melt. WEATHER Average precipitation but above average temperatures are forecasted for April for most of Tajikistan. ENERGY SECURITY Increased flows into the Nurek Cascade have resulted in the lifting of restrictions on electricity. Reports indicate that an agreement has been reached with Uzbekistan on the supply of natural gas, and deliveries restarted on 16 April. FOOD SECURITY Wheat flour prices in Khujand continue to drop while prices in Kurgan-Tube and Dushanbe remain stable, possible reflecting rail delivery delays (Kurgan-Tube) and limited roads access to the north due to heavy snow and avalanches (Dushanbe). Fuel prices have dropped slightly. The Ministry of Agriculture reports damage to crops and livestock due to severe weather in the fall of 2011/winter 2011-2012, as well as a delay in spring planting. MIGRATION AND REMITTANCES Reported migration rates for the first three months of 2012 are significantly above 2011 levels. Reported remittances are 25% above 2011 in March. These increases may indicate a reaction to shocks during the fall 2011 and winter 2011-2012. ECONOMY GDP increased from January to February by 6.9% and totaled 3,334.5 million Tajik Somoni (701 million USD). In January - February 2012, the foreign trade turnover equaled 827.1 million USD, with a negative trade balance of 415.3 million USD. -

Dushanbe Forum of Mountain Countries -2015: Water and Mountains

Dushanbe Forum of Mountain Countries -2015: Water and Mountains Dushanbe Forum of Mountain Countries - 2015: Water and Mountains AGRICULTURE & FOOD SECURITY UNDER CHANGIN G CLIMATE IN CENTRAL ASIAN MOUNTAINS: Integrated Watershed Management as a viable solution for coping with and adapting to changes Content PART 1: The Dushanbe Forum of Mountain Countries – 2015 ...................... 5 Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 8 Knowledge Fair ...................................................................................................10 Programme ......................................................................................................... 12 Forum sessions summaries ........................................................................... 21 Parallel Thematic Sessions: The Session Presentations ....................... 23 Annex 1: Resolution ........................................................................................ 56 PART 2: The UN High-Level International Conference “Water for Life”..... 59 Daily briefs ........................................................................................................... 62 Parallel Thematic session ............................................................................... 63 Report on the parallel Thematic session №3 ............................................ 67 Abbreviations AKDN Aga Khan Development Network SDC Swiss Development Cooperation CAMH Central Asia Mountain Hub (Mountain Partnership -

University Students and Professors: Multiple Opportunities for Informal Payments During University Studies Could Substitute for Lost Income

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Moderate Expectations: Barriers to Access and Complete Public Disclosure Authorized Higher Education in Tajikistan Listening to Stakeholders’ Voices During the University Entrance Exam Reform Public Disclosure Authorized June 2015 Report No: AUS7057 . Moderate Expectations: Barriers to Access and Complete Higher Education in Tajikistan Listening to Stakeholders’ Voices During the University Entrance Exam Reform . GED03 EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA . Standard Disclaimer: This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. -

Executive Summary

ASSESSMENT OF WATER USER ASSOCIATION SUPPORT PROGRAM (WUASP) May 27, 2010 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Mendez England and Associates ASSESSMENT OF WATER USER ASSOCIATION SUPPORT PROGRAM (WUASP) Report Prepared under Task Order # EPP-I-08-05-00010-00 under the WATER II Indefinite Quantity Contract, #EPP-I-00-05-00010-00 Submitted to: USAID/CAR Submitted by: Steve Lam Loren Schulze Contractor: Mendez England & Associates 4300 Montgomery Avenue, Suite 103 Bethesda, MD 20814 Tel: 301- 652 -4334 www.mendezengland.com DISCLAIMER The authors‟ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government ASSESSMENT OF WATER USER ASSOCIATION SUPPORT PROGRAM (WUASP) CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................... 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 2 1.1 Purpose of Assessment....................................................................................................... 2 1.2 The Water User Association Support Program .............................................................. 2 1.3 Assessment Team ............................................................................................................... 2 2.0 ASSESSMENT SCHEDULE AND METHODOLOGY ............................. 3 2.1 Initial Data Gathering ..................................................................................................... -

Wheat Landraces in Farmers' Fields in Tajikistan

WHEAT LANDRACES IN FARMERS’ FIELDS IN TAJIKISTAN: NATIONAL SURVEY, COLLECTION, AND CONSERVATION, 2013-2015 WHEAT LANDRACES IN FARMERS’ FIELDS IN TAJIKISTAN NATIONAL SURVEY, COLLECTION, AND CONSERVATION, 2013-2015 Bahromiddin HUSENOV Munira OTAMBEKOVA Alexey MORGOUNOV Hafiz MUMINJANOV FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Ankara, 2015 Citation: FAO, 2015. Wheat Landraces in farmers’ fields in Tajikistan: National Survey, Collection, and Conservation, 2013-2015, by B. Husenov, M. Otambekova, A. Morgounov and H.Muminjanov. Ankara, Turkey The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN: 978-92-5-108997-2 © FAO, 2015 Photographers B. Husenov and M.Otambekova FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence-request or addressed to [email protected]. -

Partoev K., Sulangov M., Melikov K., Jumakhmadov A. LO L

Partoev K., Sulangov M., Melikov K., Jumakhmadov A. LOCAL AGRO BIODIVERSITY AND TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE IN AGRICULTURE NEED TO BE PRESERVED LOCAL AGRO BIODIVERSITY AND TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE NEED TO BE PRESERVED UDK: 40.3+41+42.3 Dedicated to the 20th Independent of Republic of Tajikistan P-29 Authors: Kurbonali Partoev – senior staff scientist, candidate of agricultural science Makhmadzamon Sulangov – senior staff scientist Kurbonali Melikov - scientific associate, researcher Asomiddin Jumakhmadov – agronomist – researcher. Findings of investigation made by the staff members of the Institute of botany, plant physiology and genetics of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan, the Institute of gardening and vegetable growing of the Academy of agricultural sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan and Public Organization “Khamkori Bakhri Tarakkiyet” (“Cooperation for Development”) at cooperation with Ministry of Agriculture Republic of Tajikistan in 2007 – 2010 are collected in this book. Research on discovering and description of valuable local varieties of fruit, grain and feed crops as the main agro biodiversity component in Tajikistan was carried out in the Hissar, Rasht, Zarafshan, Istravshan and Vakhsh valleys of Tajikistan under The Christensen Fund sponsorship. For this purpose, we had to visit more than 50 villages, 30 jamoats and 18 districts of the republic, to meet and interview over 1000 farmers, women, local residents and experts on traditional rural knowledge. The most important are the results that show the preservation degree of valuable local varieties of agricultural crops and agro biodiversity as well as the ways of their preserving in the countryside as a genetic material for selection and a local resource for food security in future.