Guan Pinghu's Interpretation of Flowing Waters Lu Wang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), Piano

MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano PROGRAM JOHN WILLIAMS For New York (b. 1932) (Trans. for band by Paul Lavender) FRANK TICHELI Acadiana (b. 1958) At the Dancehall Meditations on a Cajun Ballad To Lafayette IGOR ST R AVINSKY Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments (1882–1971) Lento; Allegro Largo Allegro Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano Intermission VITTORIO Symphony No. 3 for Band GIANNINI Allegro energico (1903–1966) Adagio Allegretto Allegro con brio CENTENNIAL NOTE Vittorio Giannini (1903–1966) was an Italian-American composer calls upon the band’s martial associations, with an who joined the Manhattan School of Music faculty in 1944, where he exuberant march somewhat reminiscent of similar taught theory and composition until 1965. Among his students were efforts by Sir William Walton. Along with the sunny John Corigliano, Nicolas Flagello, Ludmila Ulehla, Adolphus Hailstork, disposition and apparent straightforwardness of works Ursula Mamlok, Fredrick Kaufman, David Amram, and John Lewis. like the Second and Third Symphonies, the immediacy MSM founder Janet Daniels Schenck wrote in her memoir, Adventure and durability of their appeal is the result of considerable in Music (1960), that Giannini’s “great ability both as a composer and as subtlety in motivic and harmonic relationships and even a teacher cannot be overestimated. In addition to this, his remarkable in voice leading. personality has made him beloved by all.” In addition to his Symphony No. -

The Butterfly Lovers' Violin Concerto by Zhanhao He and Gang Chen By

The Butterfly Lovers’ Violin Concerto by Zhanhao He and Gang Chen By Copyright 2014 Shan-Ken Chien Submitted to the graduate degree program in School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson: Prof. Véronique Mathieu ________________________________ Dr. Bryan Kip Haaheim ________________________________ Prof. Peter Chun ________________________________ Prof. Edward Laut ________________________________ Prof. Jerel Hilding Date Defended: April 1, 2014 ii The Dissertation Committee for Shan-Ken Chien certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Butterfly Lovers’ Violin Concerto by Zhanhao He and Gang Chen ________________________________ Chairperson: Prof. Véronique Mathieu Date approved: April 17, 2014 iii Abstract The topic of this DMA document is the Butterfly Lovers’ Violin Concerto. This violin concerto was written by two Chinese composers, Gang Chen and Zhahao He in 1959. It is an orchestral adaptation of an ancient legend, the Butterfly Lovers. This concerto was written for the western style orchestra as well as for solo violin. The orchestra part of this concerto has a deep complexity of music dynamics, reflecting the multiple layers of the story and echoing the soloist’s interpretation of the main character. Musically the concerto is a synthesis of Eastern and Western traditions, although the melodies and overall style are adapted from the Yue Opera. The structure of the concerto is a one-movement programmatic work or a symphonic poem. The form of the concerto is a sonata form including three sections. The sonata form fits with the three phases of the story: Falling in Love, Refusing to Marry, and Metamorphosis. -

Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2510.181699 Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China Appendix Appendix Table. Surveillance for carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospitals, Zhejiang Province, China, 2015– 2017* Years Hospitals by city Level† Strain identification method‡ excluded§ Hangzhou First 17 People's Liberation Army Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Red Cross Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou First People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Hangzhou Children's Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Hospital of Chinese Traditional Hospital 3A Phoenix 100, VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Cancer Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Xixi Hospital of Hangzhou 3A VITEK 2 Compact Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Women's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A VITEK 2 Compact The First Affiliated Hospital of Medical School of Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of 3A MALDI-TOF MS Medicine Hangzhou Second People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang People's Armed Police Corps Hospital, Hangzhou 3A Phoenix 100 Xinhua Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Cancer -

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof. Wang, Yaohua Fujian Normal University, China Intangible cultural heritage is the memory of human historical culture, the root of human culture, the ‘energic origin’ of the spirit of human culture and the footstone for the construction of modern human civilization. Ever since China joined the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004, it has done a lot not only on cognition but also on action to contribute to the protection and transmission of intangible cultural heritage. Please allow me to expatiate these on the case of Chinese nanyin(南音, southern music). I. The precious multi-values of nanyin decide the necessity of protection and transmission for Chinese nanyin. Nanyin, also known as “nanqu” (南曲), “nanyue” (南乐), “nanguan” (南管), “xianguan” (弦管), is one of the oldest music genres with strong local characteristics. As major musical genre, it prevails in the south of Fujian – both in the cities and countryside of Quanzhou, Xiamen, Zhangzhou – and is also quite popular in Taiwan, Hongkong, Macao and the countries of Southeast Asia inhabited by Chinese immigrants from South Fujian. The music of nanyin is also found in various Fujian local operas such as Liyuan Opera (梨园戏), Gaojia Opera (高甲戏), line-leading puppet show (提线木偶戏), Dacheng Opera (打城戏) and the like, forming an essential part of their vocal melodies and instrumental music. As the intangible cultural heritage, nanyin has such values as follows. I.I. Academic value and historical value Nanyin enjoys a reputation as “a living fossil of the ancient music”, as we can trace its relevance to and inheritance of Chinese ancient music in terms of their musical phenomena and features of musical form. -

Composer Performer

Capital Normal University is well-known for its role in educational and cultural transmission and innovation in China. It has set up various departments and offers complete sets of academic disciplines, including liberal arts, science, engineering, management, law, education, art, music and foreign languages etc.. It has also opened many research fields with unique oriental cultural characteristics. Music College of CNU is one of the most famous music schools in China. It comprises 7 departments serving undergraduate and graduate degrees in music education, composing, conducting, piano, vocal, Chinese and western musical instruments, recording technique, dancing,. It also serving doctoral degrees of music education, composing, theory of composing, musicology, music science as well as dancing. The Music College has its chorus troupe, national music band, Chinese and western chamber music band and dancing troupe. Composer Yangqing: Famous composer of Zhou Xueshi: composer,Professor of China. Professor, Dean of Music College Music College of CNU. of CNU. His works involves orchestral <New arrangement: Birds in the Shade>, music, chamber music, dance drama for Chinese Flute, Sheng, Xun, Pipa, Erhu and movie music, His music win a high and Percussion. The musical materials of admiration in china. Leader of this this piece originate from this work—Birds visiting group to USA. Special invited in the Shade for Chinese Flute Solo by to compose a piece of music for both Guanyue Liu. It presents an interesting Chinese and USA instrumentalists. counterpoint in ensemble and shows the technical virtuosity of performers by developing fixed melody patterns and sound patterns. Performer Zhou Shibin: Vice dean, professor Wang Chaohui: Pipa performer . -

Instrument List

Instrument List Africa: Europe: Kora, Domu, Begana, Mijwiz 1, Mijwiz 2, Arghul, Celtic & Wire Strung Harps, Mandolins, Zitter, Ewe drum collection, Udu drums, Doun Doun Collection of Recorders, Irish and other whistles, drums, Talking drums, Djembe, Mbira, Log drums, FDouble Flutes, Overtone Flutes, Sideblown Balafon, and many other African instruments. Flutes, Folk Flutes, Chanters and Bagpipes, Bodran, Hang drum, Jews harps, accordions, China: Alphorn and many other European instruments. Erhu, Guzheng, Pipa, Yuequin, Bawu, Di-Zi, Guanzi, Hulusi, Sheng, Suona, Xiao, Bo, Darangu Middle East: Lion Drum, Bianzhong, Temple bells & blocks, Oud, Santoor, Duduk, Maqrunah, Duff, Dumbek, Chinese gongs & cymbals, and various other Darabuka, Riqq, Zarb, Zills and other Middle Chinese instruments. Eastern instruments. India: North America: Sitar, Sarangi, Tambura, Electric Sitar, Small Banjo, Dulcimer, Zither, Washtub Bass, Native Zheng, Yuequin, Bansuris, Pungi Snake Charmer, Flute, Fife, Bottle Blows, Slide Whistle, Powwow Shenai, Indian Whistle, Harmonium, Tablas, Dafli, drum, Buffalo drum, Cherokee drum, Pueblo Damroo, Chimtas, Dhol, Manjeera, Mridangam, drum, Log drum, Washboard, Harmonicas Naal, Pakhawaj, Tamte, Tasha, Tavil, and many and more. other Indian instruments. Latin America: Japan: South American & Veracruz Harps, Guitarron, Taiko Drum collection, Koto, Shakuhachi, Quena, Tarka, Panpipes, Ocarinas, Steel Drums, Hichiriki, Sanshin, Shamisen, Knotweed Flute, Bandoneon, Berimbau, Bombo, Rain Stick, Okedo, Tebyoshi, Tsuzumi and other Japanese and an extensive Latin Percussion collection. instruments. Oceania & Australia: Other Asian Regions: Complete Jave & Bali Gamelan collections, Jobi Baba, Piri, Gopichand, Dan Tranh, Dan Ty Sulings, Ukeleles, Hawaiian Nose Flute, Ipu, Ba,Tangku Drum, Madal, Luo & Thai Gongs, Hawaiian percussion and more. Gedul, and more. www.garritan.com Garritan World Instruments Collection A complete world instruments collection The world instruments library contains hundreds of high-quality instruments from all corners of the globe. -

Voyager's Gold Record

Voyager's Gold Record https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyager_Golden_Record #14 score, next page. YouTube (Perlman): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVzIfSsskM0 Each Voyager space probe carries a gold-plated audio-visual disc in the event that the spacecraft is ever found by intelligent life forms from other planetary systems.[83] The disc carries photos of the Earth and its lifeforms, a range of scientific information, spoken greetings from people such as the Secretary- General of the United Nations and the President of the United States and a medley, "Sounds of Earth," that includes the sounds of whales, a baby crying, waves breaking on a shore, and a collection of music, including works by Mozart, Blind Willie Johnson, Chuck Berry, and Valya Balkanska. Other Eastern and Western classics are included, as well as various performances of indigenous music from around the world. The record also contains greetings in 55 different languages.[84] Track listing The track listing is as it appears on the 2017 reissue by ozmarecords. No. Title Length "Greeting from Kurt Waldheim, Secretary-General of the United Nations" (by Various 1. 0:44 Artists) 2. "Greetings in 55 Languages" (by Various Artists) 3:46 3. "United Nations Greetings/Whale Songs" (by Various Artists) 4:04 4. "The Sounds of Earth" (by Various Artists) 12:19 "Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047: I. Allegro (Johann Sebastian 5. 4:44 Bach)" (by Munich Bach Orchestra/Karl Richter) "Ketawang: Puspåwårnå (Kinds of Flowers)" (by Pura Paku Alaman Palace 6. 4:47 Orchestra/K.R.T. Wasitodipuro) 7. -

A List of Qin Recordings with a Spring Theme

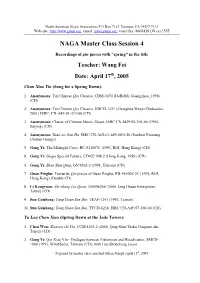

North American Guqin Association, P O Box 7113, Fremont, CA 94537-7113 Web site: http://www.guqin.org, email: [email protected], voice/fax: 8668419139 ext 1555 NAGA Master Class Session 4 Recordings of qin pieces with “spring” in the title Teacher: Wang Fei Date: April 17th, 2005 Chun Xiao Yin (Song for a Spring Dawn): 1. Anonymous: Ten Chinese Qin Classics, CDM-1074 (DoReMi, Guangzhou, 1998) (CD) 2. Anonymous: Ten Chinese Qin Classics, HDCD-1121 (Zhonghua Wenyi Chubanshe, 2001) ISRC: CN-A49-01-313-00 (CD) 3. Anonymous: Classic of Chinese Music: Guqin, ISRC CN-M29-94-306-00 (1994, Beijing) (CD) 4. Anonymous: Xiao’ao Jian Hu, ISRC CN-A65-01-649-00/A.J6 (Jiuzhou Yinxiang Chuban Gongsi) 5. Gong Yi: The Midnight Crow, RC-931007C (1993, ROI, Hong Kong) (CD) 8. Gong Yi: Guqin Special Feature, CD422 998-2 (Hong Kong, 1989) (CD) 6. Gong Yi: Shan Shui Qing, GN 9202-2 (1991, Taiwan) (CD) 7. Guan Pinghu: Favourite Qin pieces of Guan Pinghu, RB-951005-2C (1995, ROI, Hong Kong) (Double CD) 8. Li Kongyuan: Shi-shang Liu Quan, 200098268 (2000, Ling Hsuan Enterprises, Taibei) (CD) 9. Sun Guisheng: Yang Guan San Die, JRAF-1241 (1992, Taiwan) 10. Sun Guisheng: Yang Guan San Die, TYCD-0238, ISRC CN-A49-97-360-00 (CD) Yu Lou Chun Xiao (Spring Dawn at the Jade Tower): 1. Chen Wen: Xianwai zhi Yin, CCM 8103-2 (2000, Qing Shan Yishu Gongzuo-shi, Taipei) (CD) 2. Gong Yi: Qin Xiao Yin - Dialogue between Fisherman and Wood-cutter, SMCD- 1008 (1995, Wind/Solar, Taiwan) (CD); with Luo Shoucheng (xiao) Prepared by master class assistant Julian Joseph April 15th, 2005 North American Guqin Association, P O Box 7113, Fremont, CA 94537-7113 Web site: http://www.guqin.org, email: [email protected], voice/fax: 8668419139 ext 1555 3. -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

![[Ton]Spurensuche : Ernst Bloch Und Die Musik](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5658/ton-spurensuche-ernst-bloch-und-die-musik-1175658.webp)

[Ton]Spurensuche : Ernst Bloch Und Die Musik

Klappe hinten U4 U4 Buchrücken U1 U1 Klappe vorne KOLLEKTION MUSIKWISSENSCHAFT KOLLEKTION MUSIKWISSENSCHAFT MATTHIAS HENKE KOLLEKTION MUSIKWISSENSCHAFT HERAUSGEGEBEN VON MATTHIAS HENKE HERAUSGEGEBEN VON MATTHIAS HENKE HERAUSGEGEBEN VON MATTHIAS HENKE BAND 1 FRANCESCA VIDAL (HG.) BAND 1 MATTHIAS HENKE, FRANCESCA VIDAL (HG.) Matthias Henke, Francesca Vidal (Hg.) TON SPURENSUCHE Si! – das Motto der Kollektion Musikwissen- [Ton]Spurensuche [ ] ERNST BLOCH UND DIE MUSIK [TON]SPURENSUCHE schaft ist vielfältig. Zunächst spielt es auf Ernst Bloch und die Musik die Basis der Buchreihe an, den Universi- tätsverlag Siegen. Si! meint aber auch ein musikalisches Phänomen, heißt so doch der Spuren – so ist nicht nur ein Band mit den poetisch ver- Leitton einer Durskala. Last, not least will Ankündigung: trackten Erzählungen von Ernst Bloch überschrieben. FRANCESCA (HG.) VIDAL | Si! sich als Imperativ verstanden wissen, als [Ton]Spuren durchwirken vielmehr sein gesamtes Werk. ERNST BLOCH BAND 2 ein vernehmbares Ja zu einer Musikwissen- Demnach erstaunt es nicht, wenn des Philosophen Ver- Sara Beimdieke schaft, die sich zu dem ihr eigenen Potential hältnis zur Musik vielfach Gegenstand wissenschaftlicher „Der große Reiz des Kamera-Mediums“ UND DIE MUSIK bekennt, zu einer selbstbewussten Diszipli- Erörterungen war. Allerdings näherte man sich diesem Ernst Kreneks Fernsehoper Ausgerech- narität, die wirkliche Trans- oder Interdiszip- fast immer auf Metaebenen. Philologische Detailarbeit, net und Verspielt linarität erst ermöglicht. die etwa die Genesis -

Study on the Guqin Teaching Method: “Inner Understanding Through Oral Teaching”

Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2019, 7, 138-146 http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss ISSN Online: 2327-5960 ISSN Print: 2327-5952 Study on the Guqin Teaching Method: “Inner Understanding through Oral Teaching” Ye Zhao Conservatory of Music, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China How to cite this paper: Zhao, Y. (2019) Abstract Study on the Guqin Teaching Method: “In- ner Understanding through Oral Teaching”. “Inner understanding through oral teaching” is the main teaching method Open Journal of Social Sciences, 7, 138-146. that runs through Guqin for thousands of years. In order to inherit and pro- https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2019.72011 tect traditional Guqin art originally in the modern society, it’s very important Received: January 12, 2019 to research this method which is used to teach Guqin in the ancient. It con- Accepted: February 16, 2019 sists of two teaching levels: “Oral” and “Mentality”: the combination of the Published: February 19, 2019 two promotes the inheritance and development of traditional Guqin. The teaching method of “inner understanding through oral teaching” is closely Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. related to the application of the word reduction spectrum, and it is not con- This work is licensed under the Creative tradictory to “viewing teaching”. In the current society, “inner understanding Commons Attribution International through oral teaching” is of great significance to the protection and inherit- License (CC BY 4.0). ance of Guqin. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Open Access Keywords Inner Understanding through Oral Teaching, Guqin 1. What Is the Connotation of the “Inner Understanding through Oral Teaching” “Inner understanding through oral teaching” is a teaching method formed under certain historical conditions and social and humanistic environment. -

Educating Through Music from an "Initiation Into Classical Music" for Children to Confucian "Self- Cultivation" for University Students

China Perspectives 2008/3 | 2008 China and its Continental Borders Educating Through Music From an "Initiation into Classical Music" for Children to Confucian "Self- Cultivation" for University Students Zhe Ji Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/4133 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.4133 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2008 Number of pages: 107-117 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Zhe Ji, « Educating Through Music », China Perspectives [Online], 2008/3 | 2008, Online since 01 July 2011, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/4133 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.4133 © All rights reserved Articles s e Educating Through Music v i a t c From an “Initiation into Classical Music” for Children to Confucian n i “Self-Cultivation” for University Students e h p s c JI ZHE r e p Confucian discourse in contemporary China simultaneously permeates the intertwined fields of politics and education. The current Confucian revival associates the “sacred”, power and knowledge whereas modernity is characterized by a differentiation between institutions and values. The paradoxical situation of Confucianism in modern society constitutes the background of the present article that explores the case of a private company involved in promoting classical Chinese music to children and “self-cultivation” to students. Its original conception of “education through music” paves the way for a new “ethical and aesthetic” teaching method that leaves aside the traditional associations of ethics with politics. By the same token, it opens the possibility for a non-political Confucianism to provide a relevant contribution in the field of education today.