Navy Constellation (FFG-62) Class Frigate Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navy Columbia-Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program

Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 14, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R41129 Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program Summary The Navy’s Columbia (SSBN-826) class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) program is a program to design and build a class of 12 new SSBNs to replace the Navy’s current force of 14 aging Ohio-class SSBNs. Since 2013, the Navy has consistently identified the Columbia-class program as the Navy’s top priority program. The Navy procured the first Columbia-class boat in FY2021 and wants to procure the second boat in the class in FY2024. The Navy’s proposed FY2022 budget requests $3,003.0 (i.e., $3.0 billion) in procurement funding for the first Columbia-class boat and $1,644.0 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in advance procurement (AP) funding for the second boat, for a combined FY2022 procurement and AP funding request of $4,647.0 million (i.e., about $4.6 billion). The Navy’s FY2022 budget submission estimates the procurement cost of the first Columbia- class boat at $15,030.5 million (i.e., about $15.0 billion) in then-year dollars, including $6,557.6 million (i.e., about $6.60 billion) in costs for plans, meaning (essentially) the detail design/nonrecurring engineering (DD/NRE) costs for the Columbia class. (It is a long-standing Navy budgetary practice to incorporate the DD/NRE costs for a new class of ship into the total procurement cost of the first ship in the class.) Excluding costs for plans, the estimated hands-on construction cost of the first ship is $8,473.0 million (i.e., about $8.5 billion). -

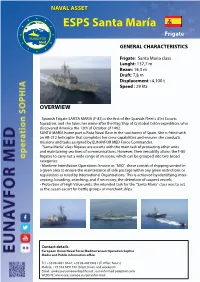

ESPS Santa María Frigate EUNAVFOR Med GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

NAVAL ASSET ESPS Santa María Frigate EUNAVFOR Med GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS Frigate: Santa Maria class Lenght: 137,7 m Beam: 14,3 m Draft: 7,8 m Displacement : 4,100 t Speed : 29 kts OVERWIEW Spanish Frigate SANTA MARÍA (F-81) is the first of the Spanish Fleet’s 41st Escorts Squadron, and she takes her name after the Flag Ship of Cristobal Colón expedition, who discovered America the 12th of October of 1492. SANTA MARÍA home port is Rota Naval Base in the southwest of Spain. She is fitted with an AB-212 helicopter that completes her crew capabilities and ensures she conducts missions and tasks assigned by EUNAVFOR MED Force Commander. “Santa María” class frigates are escorts with the main task of protecting other units and maintaining sea lines of communications. However, their versatility allows the F-80 frigates to carry out a wide range of missions, which can be grouped into two broad categories: • Maritime Interdiction Operations: known as “MIO”, these consist of shipping control in a given area to ensure the maintenance of safe passage within any given restrictions or regulations as ruled by International Organisations. This is achieved by identifying, inter- cepting, boarding, searching, and if necessary, the detention of suspect vessels; • Protection of High Value units: the intended task for the “Santa Maria” class was to act as the ocean escort for battle groups or merchant ships. Contact details European Union Naval Force Mediterranean Operation Sophia Media and Public information office Tel: +39 06 4691 9442 ; +39 06 46919451 (IT Office hours) Mobile: +39 334 6891930 (Silent hours and weekend) Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] WEBSITE: www.eeas.europa.eu/eunavfor-med. -

Britain and the Royal Navy by Jeremy Black

A Post-Imperial Power? Britain and the Royal Navy by Jeremy Black Jeremy Black ([email protected]) is professor of history at University of Exeter and an FPRI senior fellow. His most recent books include Rethinking Military History (Routledge, 2004) and The British Seaborne Empire (Yale University Press, 2004), on which this article is based. or a century and a half, from the Napoleonic Wars to World War II, the British Empire was the greatest power in the world. At the core of that F power was the Royal Navy, the greatest and most advanced naval force in the world. For decades, the distinctive nature, the power and the glory, of the empire and the Royal Navy shaped the character and provided the identity of the British nation. Today, the British Empire seems to be only a memory, and even the Royal Navy sometimes can appear to be only an auxiliary of the U.S. Navy. The British nation itself may be dissolving into its preexisting and fundamental English, Scottish, and even Welsh parts. But British power and the Royal Navy, and particularly that navy’s power projection, still figure in world affairs. Properly understood, they could also continue to provide an important component of British national identity. The Distinctive Maritime Character of the British Empire The relationship between Britain and its empire always differed from that of other European states with theirs, for a number of reasons. First, the limited authority and power of government within Britain greatly affected the character of British imperialism, especially, but not only, in the case of colonies that received a large number of British settlers. -

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Summary The USS Constellation’s career in naval service spanned one hundred years: from commissioning on July 28, 1855 at Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia to final decommissioning on February 4, 1955 at Boston, Massachusetts. (She was moved to Baltimore, Maryland in the summer of 1955.) During that century this sailing sloop-of-war, sometimes termed a “corvette,” was nationally significant for its ante-bellum service, particularly for its role in the effort to end the foreign slave trade. It is also nationally significant as a major resource in the mid-19th century United States Navy representing a technological turning point in the history of U.S. naval architecture. In addition, the USS Constellation is significant for its Civil War activities, its late 19th century missions, and for its unique contribution to international relations both at the close of the 19th century and during World War II. At one time it was believed that Constellation was a 1797 ship contemporary to the frigate Constitution moored in Boston. This led to a long-standing controversy over the actual identity of the Constellation. Maritime scholars long ago reached consensus that the vessel currently moored in Baltimore is the 1850s U.S. navy sloop-of-war, not the earlier 1797 frigate. Describe Present and Historic Physical Appearance. The USS Constellation, now preserved at Baltimore, Maryland, was built at the navy yard at Norfolk, Virginia. -

Fy15 Table of Contents Fy16 Table of Contents

FY15FY16 TABLE OF CONTENTS DOT&E Activity and Oversight FY16 Activity Summary 1 Program Oversight 7 Problem Discovery Affecting OT&E 13 DOD Programs Major Automated Information System (MAIS) Best Practices 23 Defense Agencies Initiative (DAI) 29 Defensive Medical Information Exchange (DMIX) 33 Defense Readiness Reporting System – Strategic (DRRS-S) 37 Department of Defense (DOD) Teleport 41 DOD Healthcare Management System Modernization (DHMSM) 43 F-35 Joint Strike Fighter 47 Global Command and Control System – Joint (GCCS-J) 107 Joint Information Environment (JIE) 111 Joint Warning and Reporting Network (JWARN) 115 Key Management Infrastructure (KMI) Increment 2 117 Next Generation Diagnostic System (NGDS) Increment 1 121 Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) Increment 2 123 Theater Medical Information Program – Joint (TMIP-J) 127 Army Programs Army Network Modernization 131 Network Integration Evaluation (NIE) 135 Abrams M1A2 System Enhancement Program (SEP) Main Battle Tank (MBT) 139 AH-64E Apache 141 Army Integrated Air & Missile Defense (IAMD) 143 Chemical Demilitarization Program – Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternatives (CHEM DEMIL-ACWA) 145 Command Web 147 Distributed Common Ground System – Army (DCGS-A) 149 HELLFIRE Romeo and Longbow 151 Javelin Close Combat Missile System – Medium 153 Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV) Family of Vehicles (FoV) 155 Joint Tactical Networks (JTN) Joint Enterprise Network Manager (JENM) 157 Logistics Modernization Program (LMP) 161 M109A7 Family of Vehicles (FoV) Paladin Integrated Management (PIM) 165 -

Security & Defence European

a 7.90 D European & Security ES & Defence 4/2016 International Security and Defence Journal Protected Logistic Vehicles ISSN 1617-7983 • www.euro-sd.com • Naval Propulsion South Africa‘s Defence Exports Navies and shipbuilders are shifting to hybrid The South African defence industry has a remarkable breadth of capa- and integrated electric concepts. bilities and an even more remarkable depth in certain technologies. August 2016 Jamie Shea: NATO‘s Warsaw Summit Politics · Armed Forces · Procurement · Technology The backbone of every strong troop. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles. When your mission is clear. When there’s no road for miles around. And when you need to give all you’ve got, your equipment needs to be the best. At times like these, we’re right by your side. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles: armoured, highly capable off-road and logistics vehicles with payloads ranging from 0.5 to 110 t. Mobilising safety and efficiency: www.mercedes-benz.com/defence-vehicles Editorial EU Put to the Test What had long been regarded as inconceiv- The second main argument of the Brexit able became a reality on the morning of 23 campaigners was less about a “democratic June 2016. The British voted to leave the sense of citizenship” than of material self- European Union. The majority that voted for interest. Despite all the exception rulings "Brexit", at just over 52 percent, was slim, granted, the United Kingdom is among and a great deal smaller than the 67 percent the net contribution payers in the EU. This who voted to stay in the then EEC in 1975, money, it was suggested, could be put to but ignoring the majority vote is impossible. -

Student Health Insurance Plan Faqs

Student Health Insurance Plan FAQs Table of Contents Student Health Insurance Plan (SHIP) Overview 1 Student Health Services (SHS) 3 Considering SHIP 5 SHIP Options: Basic and Plus 7 Waiving SHIP 8 Affordable Care Act (ACA) 9 Graduate Student Information: For Trainee Stipends 10 Recipients and Research Assistants, Research Fellows, Teaching Assistants, and Teaching Fellows Student Health Insurance Plan (SHIP) Overview Q: What is the Student Health Insurance Plan (SHIP)? A: SHIP is Boston University’s insurance plan for students, offered through Aetna, a large national health insurer. Q: Who is eligible for SHIP? A: Most students who attend Boston University are eligible for SHIP. Q: Am I automatically enrolled in SHIP? A: Full-time, three-quarter time, and international undergraduate and graduate students are automatically enrolled in SHIP Basic coverage. Part-time students in degree- granting programs will need to enroll. Students on campuses other than the Charles River Campus may be automatically enrolled in the Plus option; consult your program administrator for details. Post-Doctoral Fellows are eligible to voluntarily enroll in the plan. Please contact the Post-Doctoral Professional Development and Post-Doctoral Affairs Office at [email protected] to obtain an enrollment application. Q: Can I waive SHIP coverage? A: Depending on your insurance, you may be able to waive SHIP coverage if you have other coverage that meets ACA requirements. See the Affordable Care Act (ACA) section of this FAQs document to learn more about ACA requirements. Page 1 2021/22 Student Health Insurance Plan FAQs The chart below indicates which student types may waive their SHIP coverageand under what circumstances this waiver is permitted. -

International Programs Key to Security Cooperation an Interview With

SURFACE SITREP Page 1 P PPPPPPPPP PPPPPPPPPPP PP PPP PPPPPPP PPPP PPPPPPPPPP Volume XXXII, Number 3 October 2016 International Programs Key to Security Cooperation An Interview with RADM Jim Shannon, USN, Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy for International Programs Conducted by CAPT Edward Lundquist, USN (Ret) Tell me about your mission, and what intellectual property of the technology you have — your team —in order to that we developed for our Navy execute that mission? programs – that includes the Marine It’s important to understand what your Corps. These are Department of Navy authorities are in any job you come Programs, for both the Navy and Marine into. You just can’t look at a title and Corps, across all domains – air, surface, determine what your job or authority subsurface, land, cyber, and space, is. In this case, there are Secretary everywhere, where the U.S. Navy or of the Navy (SECNAV) instructions; the Department of the Navy is the lead there’s law; and then there’s federal agent. As the person responsible for government regulations on how to this technology’s security, I obviously do our job. And they all imply certain have a role where I determine “who levels of authority to the military do we share that information with and departments – Army, Navy, and Air how do we disclose that information.” Force. And then the Office of the The way I exercise that is in accordance Secretary of Defense (OSD) has a with the laws, the Arms Export Control separate role, but altogether, we work Act. -

Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES CSC 28 / CCEM 28 MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES (MDS) THESIS THE CORVETTE - A SHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY CANADIAN NAVY LA CORVETTE - UN NAVIRE POUR LA MARINE CANADIENNE DU 21E SIÈCLE By/par LCdr/capc Pierre Bédard This paper was written by a student attending La présente étude a été rédigée par un stagiaire the Canadian Forces College in fulfilment of one du Collège des Forces canadiennes pour of the requirements of the Course of Studies. satisfaire à l'une des exigences du cours. The paper is a scholastic document, and thus L'étude est un document qui se rapporte au contains facts and opinions, which the author cours et contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and correct for que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et the subject. -

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 30, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33745 SUMMARY RL33745 Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) September 30, 2021 Program: Background and Issues for Congress Ronald O'Rourke The Aegis ballistic missile defense (BMD) program, which is carried out by the Missile Defense Specialist in Naval Affairs Agency (MDA) and the Navy, gives Navy Aegis cruisers and destroyers a capability for conducting BMD operations. BMD-capable Aegis ships operate in European waters to defend Europe from potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as Iran, and in in the Western Pacific and the Persian Gulf to provide regional defense against potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as North Korea and Iran. MDA’s FY2022 budget submission states that “by the end of FY 2022 there will be 48 total BMDS [BMD system] capable ships requiring maintenance support.” The Aegis BMD program is funded mostly through MDA’s budget. The Navy’s budget provides additional funding for BMD-related efforts. MDA’s proposed FY2021 budget requested a total of $1,647.9 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in procurement and research and development funding for Aegis BMD efforts, including funding for two Aegis Ashore sites in Poland and Romania. MDA’s budget also includes operations and maintenance (O&M) and military construction (MilCon) funding for the Aegis BMD program. Issues for Congress regarding the Aegis BMD program include the following: whether to approve, reject, or modify MDA’s annual procurement and research and development funding requests for the program; the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the execution of Aegis BMD program efforts; what role, if any, the Aegis BMD program should play in defending the U.S. -

Putting the 'War' Back Into Minor War Vessels: Utilising the Arafura Class

Tac Talks Issue: 18 | 2021 Putting the ‘War’ back into Minor War Vessels: utilising the Arafura Class to reinvigorate high intensity warfighting in the Patrol Force By LEUT Brett Willis Tac Talks © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print, and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice and imagery metadata) for your personal, non-commercial use, or use within your organisation. This material cannot be used to imply an endorsement from, or an association with, the Department of Defence. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Tac Talks Introduction It is a curious statistic of the First World War that more sailors and officers were killed in action on Minor War Vessels than on Major Fleet Units in all navies involved in the conflict. For a war synonymous with the Dreadnought arms race and the clash of Battleships at Jutland the gunboats of the Edwardian age proved to be the predominant weapon of naval warfare. These vessels, largely charged with constabulary duties pre-war, were quickly pressed into combat and played a critical role in a number of theatres rarely visited in the histories of WWI. I draw attention to this deliberately for the purpose of this article is to advocate for the exploitation of the current moment of change in the RAN Patrol Boat Group and configure it to better confront the very real possibility of a constabulary force being pressed into combat. This article will demonstrate that prior planning & training will create a lethal Patrol Group that poses a credible threat to all surface combatants by integrating guided weapons onto the Arafura Class.