German Verbs & Essential of Grammar: V. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

Verbs Show an Action (Eg to Run)

VERBS Verbs show an action (e.g. to run). The tricky part is that sometimes the action can't be seen on the outside (like run) – it is done on the inside (e.g. to decide). Sometimes the action even has to do with just existing, in other words to be (e.g. is, was, are, were, am). Tenses The three basic tenses are past, present and future. Past – has already happened Present – is happening Future – will happen To change a word to the past tense, add "-ed" (e.g. walk → walked). ***Watch out for the words that don't follow this (or any) rule (e.g. swim → swam) *** To change a word to the future tense, add "will" before the word (e.g. walk → will walk BUT not will walks) Exercise 1 For each word, write down the correct tense in the appropriate space in the table below. Past Present Future dance will plant looked runs shone will lose put dig Spelling note: when "-ed" is added to a word ending in "y", the "y" becomes an "i" e.g. try → tried These are the basic tenses. You can break present tense up into simple present (e.g. walk), present perfect (e.g. has walked) and present continuous (e.g. is walking). Both past and future tenses can also be broken up into simple, perfect and continuous. You do not need to know these categories, but be aware that each tense can be found in different forms. Is it a verb? Can it be acted out? no yes Can it change It's a verb! tense? no yes It's NOT a It's a verb! verb! Exercise 2 In groups, decide which of the words your teacher gives you are verbs using the above diagram. -

Modals and Auxiliaries 12

Verbs: Modals and Auxiliaries 12 An auxiliary is a helping verb. It is used with a main verb to form a verb phrase. For example, • She was calling her friend. Here the word calling is the main verb and the word was is an auxiliary verb. The words be , have , do , can , could , may , might , shall , should , must , will , would , used , need , dare , ought are called auxiliaries . The verbs be, have and do are often referred to as primary auxiliaries. They have a grammatical function in a sentence. The rest in the above list are called modal auxiliaries, which are also known as modals. They express attitude like permission, possibility, etc. Note the forms of the primary auxiliaries. Auxiliary verbs Present tense Past tense be am, is, are was, were do do, does did have has, have had The table below illustrates the application of these primary verbs. Primary auxiliary Function Example used in the formation of She is sewing a dress. continuous tenses I am leaving tomorrow. be in sentences where the The missing child was action is more important found. than the subject 67 EBC-6_Ch19.indd 67 8/12/10 11:47:38 PM when followed by an We are to leave next infinitive, it is used to week. indicate a plan or an arrangement denotes command You are to see the Principal right now. used to form the perfect The carpenter has tenses worked well. have used with the infinitive I had to work that day. to indicate some kind of obligation used to form the He doesn’t work at all. -

Basic German: a Grammar and Workbook

BASIC GERMAN: A GRAMMAR AND WORKBOOK Basic German: A Grammar and Workbook comprises an accessible reference grammar and related exercises in a single volume. It introduces German people and culture through the medium of the language used today, covering the core material which students would expect to encounter in their first years of learning German. Each of the 28 units presents one or more related grammar topics, illustrated by examples which serve as models for the exercises that follow. These wide-ranging and varied exercises enable the student to master each grammar point thoroughly. Basic German is suitable for independent study and for class use. Features include: • Clear grammatical explanations with examples in both English and German • Authentic language samples from a range of media • Checklists at the end of each Unit to reinforce key points • Cross-referencing to other grammar chapters • Full exercise answer key • Glossary of grammatical terms Basic German is the ideal reference and practice book for beginners but also for students with some knowledge of the language. Heiner Schenke is Senior Lecturer in German at the University of Westminster and Karen Seago is Course Leader for Applied Translation at the London Metropolitan University. Other titles available in the Grammar Workbooks series are: Basic Cantonese Intermediate Cantonese Basic Chinese Intermediate Chinese Intermediate German Basic Polish Intermediate Polish Basic Russian Intermediate Russian Basic Welsh Intermediate Welsh Titles of related interest published -

Verbnet Guidelines

VerbNet Annotation Guidelines 1. Why Verbs? 2. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource 3. VerbNet Contents a. The Hierarchy b. Semantic Role Labels and Selectional Restrictions c. Syntactic Frames d. Semantic Predicates 4. Annotation Guidelines a. Does the Instance Fit the Class? b. Annotating Verbs Represented in Multiple Classes c. Things that look like verbs but aren’t i. Nouns ii. Adjectives d. Auxiliaries e. Light Verbs f. Figurative Uses of Verbs 1 Why Verbs? Computational verb lexicons are key to supporting NLP systems aimed at semantic interpretation. Verbs express the semantics of an event being described as well as the relational information among participants in that event, and project the syntactic structures that encode that information. Verbs are also highly variable, displaying a rich range of semantic and syntactic behavior. Verb classifications help NLP systems to deal with this complexity by organizing verbs into groups that share core semantic and syntactic properties. VerbNet (Kipper et al., 2008) is one such lexicon, which identifies semantic roles and syntactic patterns characteristic of the verbs in each class and makes explicit the connections between the syntactic patterns and the underlying semantic relations that can be inferred for all members of the class. Each syntactic frame in a class has a corresponding semantic representation that details the semantic relations between event participants across the course of the event. In the following sections, each component of VerbNet is identified and explained. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource VerbNet is a lexicon of approximately 5800 English verbs, and groups verbs according to shared syntactic behaviors, thereby revealing generalizations of verb behavior. -

Modeling the Position and Inflection of Verbs in English to German

Modeling the position and inflection of verbs in English to German machine translation Von der Fakult¨atInformatik, Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik der Universit¨at Stuttgart zur Erlangung der W¨urdeeines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Abhandlung. Vorgelegt von Anita Ramm aus Vukovar, Kroatien Hauptberichter Prof. Dr. Alexander Fraser 1. Mitberichterin PD Dr. Sabine Schulte im Walde 2. Mitberichter Prof. Dr. Jonas Kuhn Tag der m¨undlichen Pr¨ufung:23.03.2018 Institut f¨urMaschinelle Sprachverarbeitung der Universit¨atStuttgart 2018 Abstract Machine translation (MT) is automatic translation of speech or text from a source lan- guage (SL) into a target language (TL). Machine translation is performed without hu- man interaction: a text or a speech signal is used as input to a computer program which automatically generates translation of the input data. There are two main approaches to machine translation: rule-based and corpus-based. Rule-based MT systems rely on manually or semi-automatically acquired rules which describe lexical, as well as syntactic correspondences between SL and TL. Corpus-based methods learn such correspondences automatically using large sets of parallel texts, i.e., texts which are translations of each other. Corpus-based methods such as statistical machine translation (SMT) and neural machine translation (NMT) rely on statistics which express the probability of translat- ing a specific SL translation unit into a specific TL unit (typically, word and/or word sequence). While SMT is a combination of different statistical models, NMT makes use of a neural network which encodes parallel SL and TL contexts in a more sophisticated way. Many problems have been observed when translating from English into German using SMT. -

A Concise History of English a Concise Historya Concise of English

A Concise History of English A Concise HistoryA Concise of English Jana Chamonikolasová Masarykova univerzita Brno 2014 Jana Chamonikolasová chamonikolasova_obalka.indd 1 19.11.14 14:27 A Concise History of English Jana Chamonikolasová Masarykova univerzita Brno 2014 Dílo bylo vytvořeno v rámci projektu Filozofická fakulta jako pracoviště excelentního vzdě- lávání: Komplexní inovace studijních oborů a programů na FF MU s ohledem na požadavky znalostní ekonomiky (FIFA), reg. č. CZ.1.07/2.2.00/28.0228 Operační program Vzdělávání pro konkurenceschopnost. © 2014 Masarykova univerzita Toto dílo podléhá licenci Creative Commons Uveďte autora-Neužívejte dílo komerčně-Nezasahujte do díla 3.0 Česko (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 CZ). Shrnutí a úplný text licenčního ujednání je dostupný na: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/cz/. Této licenci ovšem nepodléhají v díle užitá jiná díla. Poznámka: Pokud budete toto dílo šířit, máte mj. povinnost uvést výše uvedené autorské údaje a ostatní seznámit s podmínkami licence. ISBN 978-80-210-7479-8 (brož. vaz.) ISBN 978-80-210-7480-4 (online : pdf) ISBN 978-80-210-7481-1 (online : ePub) ISBN 978-80-210-7482-8 (online : Mobipocket) Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................4 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................5 Abbreviations and Symbols ...................................................................................6 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................7 -

Multilingual Facilitation

Multilingual Facilitation Honoring the career of Jack Rueter Mika Hämäläinen, Niko Partanen and Khalid Alnajjar (eds.) Multilingual Facilitation This book has been authored for Jack Rueter in honor of his 60th birthday. Mika Hämäläinen, Niko Partanen and Khalid Alnajjar (eds.) All papers accepted to appear in this book have undergone a rigorous peer review to ensure high scientific quality. The call for papers has been open to anyone interested. We have accepted submissions in any language that Jack Rueter speaks. Hämäläinen, M., Partanen N., & Alnajjar K. (eds.) (2021) Multilingual Facilitation. University of Helsinki Library. ISBN (print) 979-871-33-6227-0 (Independently published) ISBN (electronic) 978-951-51-5025-7 (University of Helsinki Library) DOI: https://doi.org/10.31885/9789515150257 The contents of this book have been published under the CC BY 4.0 license1. 1 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Tabula Gratulatoria Jack Rueter has been in an important figure in our academic lives and we would like to congratulate him on his 60th birthday. Mika Hämäläinen, University of Helsinki Niko Partanen, University of Helsinki Khalid Alnajjar, University of Helsinki Alexandra Kellner, Valtioneuvoston kanslia Anssi Yli-Jyrä, University of Helsinki Cornelius Hasselblatt Elena Skribnik, LMU München Eric & Joel Rueter Heidi Jauhiainen, University of Helsinki Helene Sterr Henry Ivan Rueter Irma Reijonen, Kansalliskirjasto Janne Saarikivi, Helsingin yliopisto Jeremy Bradley, University of Vienna Jörg Tiedemann, University of Helsinki Joshua Wilbur, Tartu Ülikool Juha Kuokkala, Helsingin yliopisto Jukka Mettovaara, Oulun yliopisto Jussi-Pekka Hakkarainen, Kansalliskirjasto Jussi Ylikoski, University of Oulu Kaisla Kaheinen, Helsingin yliopisto Karina Lukin, University of Helsinki Larry Rueter LI Līvõd institūt Lotta Jalava, Kotimaisten kielten keskus Mans Hulden, University of Colorado Marcus & Jackie James Mari Siiroinen, Helsingin yliopisto Marja Lappalainen, M. -

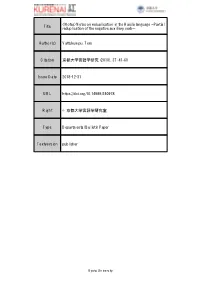

Title <Notes>Notes on Reduplication in the Haisla Language --Partial

<Notes>Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language --Partial Title reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb-- Author(s) Vattukumpu, Tero Citation 京都大学言語学研究 (2018), 37: 41-60 Issue Date 2018-12-31 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/240978 Right © 京都大学言語学研究室 Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 京都大学言語学研究 (Kyoto University Linguistic Research) 37 (2018), 41 –60 Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language Ü Partial reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb Ü Tero Vattukumpu Abstract: In this paper I will point out that, according to my data, a plural form of the negative auxiliary verb formed by means of partial reduplication exists in the Haisla language in contrary to a description on the topic in a previous study. The plural number of the subject can, and in many cases must, be indicated by using a plural form of at least one of the components of the predicate, i.e. either an auxiliary verb (if there is one), the semantic head of the predicate or both. Therefore, I have examined which combinations of the singular and plural forms of the negative auxiliary verb and different semantic heads of the predicate are judged to be acceptable by native speakers of Haisla. My data suggests that – at least at this point – it seems to be impossible to make convincing generalizations about any patterns according to which the acceptability of different combinations could be determined *. Keywords: Haisla, partial reduplication, negative auxiliary verb, plural, root extension 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to introduce some preliminary notes about reduplication in the Haisla language from a morphosyntactic point of view as a first step towards a better understanding and a more comprehensive analysis of all the possible patterns of reduplication in the language. -

Making Sense of Grammatical Variation in Norwegian Marianne Brodahl

1 Making sense of grammatical variation in Norwegian Marianne Brodahl Sameien, Eivor Finset Spilling & Hans-Olav Enger1 Abstract This study examines two examples of grammatical variation in Norwegian inflection, strong versus weak verb conjugation and affixal versus periphrastic adjective comparison. The main claim is that they are not as arbitrary as one may think, they rather indicate a division of labour. The strong verb inflection tends to be motivated not only by phonology, but also by semantics. The affixal and periphrastic adjective comparisons tend to be used with different sets of adjectives and for different semantic purposes. These observations support the Principle of Contrast, the idea that a difference in forms normally will relate to a difference in some kind of meaning. Key words: inflection, semantics, verb conjugation, adjective comparison, Principle of Contrast 1 Introduction 1 This paper is based on research carried out by the first author (section 2, cf. Nilsen 2012) and the second author (section 3, cf. Spilling 2012, Spilling & Haugen 2013, 2014) during their MA studies, supervised by the third author, who also drafted this paper. The authors are jointly responsible. We wish to thank the workshop organisers, our audience, and, last but not least, the reviewers, for very valuable input. 2 In the introduction to this volume, the editors suggest that the language users’ choice of grammatical variants is “far from arbitrary but depends on a wide array of factors from various domains”. This insight can be related to the Principle of Contrast, the idea that “speakers take every difference in forms to mark a difference in meaning” (Clark 1993: 64) – when ‘meaning’ is construed so as to include sociolinguistic and stylistic variation. -

4 the Sentence, Auxiliary Verbs, and Recursion

Introduction to Configurational Syntax Chapter 4 : Chapter 4. 4 The Sentence, Auxiliary Verbs, and Recursion 4.1 Introduction In this chapter the sentence and the verb (predicate) phrase whose head is an auxiliary verb are formally introduced. These two categories do not appear to follow the universal expansion of XP proposed in Chapter 2. In the Principles and Parameters framework of syntax the structure of the sentence can be shown to fol- low the universal expansion of XP. However, the analysis of the sentence given the category CP1 is considered too complex to be covered here. The analyses given here follow the earlier standard views on the structure of the sentence. 4.2 The Sentence At first glance, note that the sentence contains a NP and a VP: (297)a. The moon orbits around the earth. b. [NP the moon ] [VP orbits around the earth ]. We can state the expansion of S (sentence) as: (298) The Expansion of S [1] S ˘ NP VP. The structure for (297 is: (299) [S [NP The moon ] [VP orbits around the earth]] Up to this point we have claimed that all constituents contain a head and a complement. If this is the case then what is the head of S? In advanced work it can be shown to be either tense in some points of view, or the verb in other points of view. In some sense both points of view or correct; however, it is too complex a matter to attempt to explain this here. We will adopt the above expansion, which is traditional and found in most texts, and note that the verb is the unexplained head of the sentence. -

Verb Phrase, Or VP

VP Study Guide In the Logic Study Guide, we ended with a logical tree diagram for WANT (BILL, LEAVE (MARY)), in both unlabelled: WANT BILL LEAVE MARY and labelled versions: P WANT BILL P LEAVE MARY We remarked that one could label the Predicate and Argument nodes as well, and that it was common to use S instead of P to label propositions in such logical tree structures in linguistics. It is also com- mon, in practice, to use V to label Predicates, and N (or NP, standing for Noun Phrase) to label Ar- guments. This would produce the following diagram: S V NP NP Subject Formation WANT BILL S V NP LEAVE MARY Note that, while these two predicates are in fact verbs, and the arguments are nouns, that’s not always the case, and one may use V loosely to label any Predicate node, whatever its syntactic class might be. This kind of structural description, intermediate between logic and surface syntax, is called a deep structure; we say this diagram represents the deep structure of Bill wants Mary to leave. Roughly speaking, deep structures are intended to represent the meaning of the sentence, stripped to its essentials. The deep structures are then related to the actual sentence by a series of relational rules. For instance, one such rule is that in English, there must be a subject NP, and it precedes the verb, instead of coming after it, as here. So we relate this structure with the following one by a rule of Subject Formation, which applies to every deep structure towards the end of the derivation (the series of rule applications; a number of other rules would have already applied earlier, producing the other differences).