{PDF EPUB} the Day After Tomorrow by Robert A. Heinlein Sixth Column (The Day After Tomorrow) by Robert A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Librarian As Fair Witness: a Comparison of Heinlein's Futuristic

LIBRES Library and Information Science Research Electronic Journal Volume 21, Issue 1, March 2011 Librarian as Fair Witness: A Comparison of Heinlein’s Futuristic Occupation and Today’s Evolving Information Professional Julie M. Still Paul Robeson Library Rutgers University Camden, NJ [email protected] There has been a continuing discussion in library literature on the library as place and on the image of librarians in popular media, but there is little information on the librarian as person. The discussion on librarianship as a profession tends to focus on technology and not so much the people, other than the people skills needed in reference or teaching skills needed for instruction. The worth of the individual librarian tends to get lost in the shuffle. Before we disappear into the machine, it is useful to look at other future scenarios and similar occupations, either reality based or fiction. In this particular case, it is interesting to compare librarians to those in an occupation created by a renowned science fiction author. Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, his most famous and most controversial novel, is a science fiction classic. The science fiction community recognized it with a Hugo Award, and the book was the first science fiction title to be on the New York Times bestseller list (Stover, 1987, p. 45). Heinlein outlined the novel in 1949 and finished the first draft in 1955 but on the advice of his wife set it aside. It was not published until 1961. The manuscript was edited heavily and an uncut version was published in 1991. -

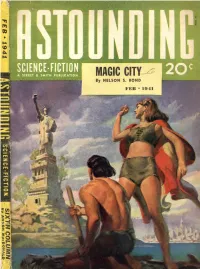

AND HE BUILT a CROOKED HOUSE Robert Heinlein

NELSON FEB 1941 p®llKfP WM — Look out for a COLD . .watch your THROAT gargle ListerineQuick! A careless sneeze, or an explosive cough, can shoot after a Listerine gargle. Even one hour after, reduc- troublesome germs in your direction at mile-a- tions up to 80% in the number of surface germs minute speed. In case they invade the tissues of associated with colds and sore throat were noted. your throat, you may be in for throat irritation, a That is why, we believe, Listerine in the last nine cold—or worse. years has built up such an impressive test record If you have been thus exposed, better gargle against colds . why thousands of people gargle witli it at first hint a sore throat. with Listerine Antiseptic at your earliest oppor- the of cold or simple tunity . Listerine kills millions of thegerms on mouth Fewer and Milder Colds in Tests and throat surfaces known as "secondary invaders” These tests showed that those who gargled with . often helps render them powerless to invade Listerine twice a day had fewer colds, milder colds, the tissue and aggravate infection. Used early and and colds of shorter duration than those who did often, Listerine may head off a cold, or reduce the not gargle. And fewer sore throats, also. severity of one already started. So remember, if you have been exposed to others Amazing Germ Reductions in Tests suffering from colds, if you feel a cold coming on, Tests have shown germ reductions ranging to gargle Listerine quick.! on mouth and throat surfaces fifteen minutes Lambert Pharmacal Co., St. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Grumbles from the Grave

GRUMBLES FROM THE GRAVE Robert A. Heinlein Edited by Virginia Heinlein A Del Rey Book BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK For Heinlein's Children A Del Rey Book Published by Ballantine Books Copyright © 1989 by the Robert A. and Virginia Heinlein Trust, UDT 20 June 1983 All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint the following material: Davis Publications, Inc. Excerpts from ten letters written by John W. Campbell as editor of Astounding Science Fiction. Copyright ® 1989 by Davis Publications, Inc. Putnam Publishing Group: Excerpt from the original manuscript of Podkayne of Mars by Robert A. Heinlein. Copyright ® 1963 by Robert A. Heinlein. Reprinted by permission of the Putnam Publishing Group. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 89-6859 ISBN 0-345-36941-6 Manufactured in the United States of America First Hardcover Edition: January 1990 First Mass Market Edition: December 1990 CONTENTS Foreword A Short Biography of Robert A. Heinlein by Virginia Heinlein CHAPTER I In the Beginning CHAPTER II Beginnings CHAPTER III The Slicks and the Scribner's Juveniles CHAPTER IV The Last of the Juveniles CHAPTER V The Best Laid Plans CHAPTER VI About Writing Methods and Cutting CHAPTER VII Building CHAPTER VIII Fan Mail and Other Time Wasters CHAPTER IX Miscellany CHAPTER X Sales and Rejections CHAPTER XI Adult Novels CHAPTER XII Travel CHAPTER XIII Potpourri CHAPTER XIV Stranger CHAPTER XV Echoes from Stranger AFTERWORD APPENDIX A Cuts in Red Planet APPENDIX B Postlude to Podkayne of Mars—Original Version APPENDIX C Heinlein Retrospective, October 6, 1988 Bibliography Index FOREWORD This book does not contain the polished prose one normally associates with the Heinlein stories and articles of later years. -

Fantasy Anthology Index 1

THA FANTASY ANTHOLOGY INDEX .. - Sam Moskowitz EDITORS Alex Osheroff I0r Fantasy Amateur Press 2)istributiun by gam ‘-W^z^S-Jell^^ Kew jerSey0 SLAN-pPtr^.^PiON AND EXPLANATION by gam Moskowitz Tamnc; v ~$US tltle ’’Fantasy Times” was appropriated by view t-i+ipT SS1-f°r on hls news publication so I had. to get a r--on-r TT:tf ^^ograph machine;, given me as a present by James who wanted ?? hS, JevG1°FG<i to bo the property of John Ba Michel end } - * r®, a“cnabla t0 a cash offer. -George Ro Pox to t-k^Vt^n? tko nonine over and the latter decided end T h-v^ fantasy Commentator” (a commendable motive) sumo^h't bQcCW of Michel in the process but I as- crux of th < s2mc °F suitable arrangemente The no,rr t ■'r^/c.r ‘tnat I couldrMt publish oven with a title good st-rcMq ™°8rG^’ Rewriter keys were too worn to type is no question of my competence in regard to tvS't’- J ^°f '2^i^i&s s£j£c.)..-l!r.. Osheroff into _3iinc tiiu stencilo c.nd induced (an even politer term) Mro Tourrsi ?* I-tooiaoa upon 6 JSLiSXn u^srt* yn index, yet having a utility value to those ■“ _ dn t .oxm ^nem, .to those who could^t make up their minds whether to buy them o-whn5 HnJnT? ®31lc2tors ?ho wantod to check on duplication and the s J didn-t wc-nt to yank out the whole volume to check on a ’ title Thu contribution of Wo Gardner is published as a public bchloa^ri ty t tnCt l70rthy register his proper NAPA credits. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

Forte JA T 2010.Pdf (404.2Kb)

“We Werenʼt Kidding” • Prediction as Ideology in American Pulp Science Fiction, 1938-1949 By Joseph A. Forte Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Robert P. Stephens (chair) Marian B. Mollin Amy Nelson Matthew H. Wisnioski May 03, 2010 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: Astounding Science-Fiction, John W. Campbell, Jr., sci-fi, science fiction, pulp magazines, culture, ideology, Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, A. E. van Vogt, American exceptionalism, capitalism, 1939 Worldʼs Fair, Cold War © 2010 Joseph A. Forte “We Werenʼt Kidding” Prediction as Ideology in American Pulp Science Fiction, 1938-1949 Joseph A. Forte ABSTRACT In 1971, Isaac Asimov observed in humanity, “a science-important society.” For this he credited the man who had been his editor in the 1940s during the period known as the “golden age” of American science fiction, John W. Campbell, Jr. Campbell was editor of Astounding Science-Fiction, the magazine that launched both Asimovʼs career and the golden age, from 1938 until his death in 1971. Campbell and his authors set the foundation for the modern sci-fi, cementing genre distinction by the application of plausible technological speculation. Campbell assumed the “science-important society” that Asimov found thirty years later, attributing sci-fi ascendance during the golden age a particular compatibility with that cultural context. On another level, sci-fiʼs compatibility with “science-important” tendencies during the first half of the twentieth-century betrayed a deeper agreement with the social structures that fueled those tendencies and reflected an explication of modernity on capitalist terms. -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

Vop #135 / 3 College

#135 Visions of Paradise #135 Contents The Passing Scene................................................................................................page 3 November 2008 Wondrous Stories................................................................................................page 5 Galactic Empires ... Farmer in the Sky ... Heinlein’s Children . Slick Willie’s Used Car World.............................................................…...........page 9 Part One On the Lighter Side............................................................................................page 16 Jokes by Bill Sabella _\\|//_ ( 0_0 ) ___________________o00__(_)__00o_________________ Robert Michael Sabella E-mail [email protected] Personal blog: http://adamosf.blogspot.com/ Sfnal blog: http://visionsofparadise.blogspot.com/ Fiction blog: http://bobsabella.livejournal.com/ Available online at http://efanzines.com/ Copyright ©November, 2008, by Gradient Press Available for trade, letter of comment or request Artwork Sheryl Birkhead ………………. cover Brad Foster ………………….page 8 The Passing Scene November 2008 Jean and I ended October by staying home on Halloween instead of going shopping. However, we had our usual small total of about 10 trick or treaters, so it was a relaxing night. The next day, after going to the YMCA in the morning, we had a quick lunch at a diner (which used to be as prevalent in New Jersey as mushrooms in a field, but recently have diminished to one every few towns) followed by a ride to Newark Airport to pick up Mark and Kate who flew back from a week at Disney World. They had a good week there, climaxed by a huge Halloween party at the Magic Kingdom so that they came home with two huge bags filled with candy. November is the month of the Indian Culture Club’s annual Family Diwali Dinner, and it was very successful. The officers did a good job planning it, the families brought lots of food, and everybody enjoyed themselves. -

The Multidimensional Guide to Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Twentieth Century, Volume 1

THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL GUIDE TO SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, VOLUME 1 EDITED BY NAT TILANDER 2 Copyright © 2010 by Nathaniel Garret Tilander All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted by any means—whether auditory, graphic, mechanical, or electronic—without written permission of both publisher and author, except in the case of brief excerpts used in critical articles and reviews. Unauthorized reproduction of any part of this work is illegal and is punishable by law. Cover art from the novella Last Enemy by H. Beam Piper, first published in the August 1950 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, and illustrated by Miller. Image downloaded from the ―zorger.com‖ website which states that the image is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain License. Additional copyrighted materials incorporated in this book are as follows: Copyright © 1949-1951 by L. Sprague de Camp. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1951-1979 by P. Schuyler Miller. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1975-1979 by Lester Del Rey. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1978-1981 by Spider Robinson. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1979-1999 by Tom Easton. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1950-1954 by J. Francis McComas. These articles originally appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction. Copyright © 1950-1959 by Anthony Boucher. These articles originally appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction. Copyright © 1959-1960 by Damon Knight. These articles originally appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction. -

Selected Scifi 201102.Xlsx

Selected Used SciFi Books- Subject to availability - Call/email store to receive purchasing link ([email protected] 540206-2505) StorePri AuthorsLast Title EAN Publisher ce Cross-Currents: Storm Season, The Face of Chaos, Abbey, Robert Lynn Asprin and Lynn B000GPXLOQ Nelson Doubleday,. $8.00 and Wings of Omen Adams, Douglas Life, The Universe and Everything 9780517548745 Harmony Books $8.00 Adams, Douglas Mostly Harmless 9781127539635 BALLANTINE BOOKS $15.00 Adams, Douglas So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish 9780795326516 HARMONY BOOKS $6.00 Adams, Douglas The Restaurant at the End of the Universe 9780517545355 Harmony $8.00 Adams, Richard MAIA 9780394528571 Knopf $8.00 Alan, Foster Dean Midworld B001975ZFI Ballentine $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Helliconia Summer (Helliconia Trilogy, Book Two) 9781111805173 Atheneum / $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Non-Stop B0057JRIV8 Carroll & Graf $10.00 Aldiss, Brian Wilson Helliconia Winter (Helliconia, 3) 9780689115417 Atheneum $7.00 Allen, Roger E. Isaac Asimov's Inferno 9780441000234 Ace Trade $6.00 Allen, Roger Macbride Isaac Asimov's Utopia 9781857982800 Orion Publishing Co $8.00 Allston, Aaron Enemy lines (Star wars, The new Jedi order) 9780739427774 Science Fiction $15.00 Anderson, Kevin J and Rebecca The Rise of the Shadow Academy 9781568652115 Guild America $15.00 Moesta Anderson, Kevin J,Herbert, Brian Hunters of Dune 9780765312921 Tor Books $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. A Forest of Stars: The Saga of Seven Suns Book 2 9780446528719 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Darksaber (Star Wars) 9780553099744 Spectra $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Hidden Empire: The Saga of Seven Suns - Book 1 9780446528627 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. -

Disclave 1970

DISCLAVE 1970 Murray Leinster Guest of Honor Skyline Inn May 15, 16, 17 Washington, D.C. Sponsored by the WASHINGTON SCIENCE FICTION ASSOCIATION. Jay Haldeman - Chairman Recent Guests of Honor 1969 - Lester Del Rey 1968 - Robert Silverberg 1967 - Jack Gaughan 1966 - Roger Zelazny Copyright 1970© Jac* C Haldeman II MURRAY LEINSTER (WILL F. JENKINS) A BIBLIOGRAPHY compiled by Mark Owings Adapter—ASF 8/46; Brit 8/48 City on the Moon—Avalon: NY, 1957, pp. Aliens, The—ASF 8/59; in The Aliens(q.v.) 224, $2.75; Ace: NY. 1958, wpps 151,35$ with Men on the Moon, ed. Wollheim; as Aliens, The — Berkeley: NY, 1960, wpps 144, Sabotage sur la Lune. tr. Michel Averlant, 35$. Contents: The Aliens, Anthropological Ditis: Paris. 1961.1 NF Note, Fugitive from Space, The Skit-Tree Colonial Survey — Gnome: NY. 1957, pp. Planet, Thing from the Sky 185, $3.00, dj Wood; Avon:NY, 1957, Amateur Alchemist, The—TWS Fall/54 wpps 171, 35$ as The Planet Explorer. Contents: Solar Constant, Sand Doom, Ambulance Made Two Trips, The— Combat Team, The Swamp was Upside ASF 4/60 Down Anthropological Note — F&SF 4/57; F&SF Combat Team — see Exploration Team (Aust) #14, 8/58; in The Aliens (q.v.) Conquest of the Stars—see Proxima Cen Assignment on Pasik—TWS 2/49 (as by tauri William Fitzgerald);POPULAR SF (Aust) Corianis Disaster, The — SFS 5/60; included #1, 7/53; included in Adventures on in Seven Come Infinity, ed. Groff Conklin Other Planets, ed. Donald A. Wollheim (Gold Medal; NY, 1966, wpps 222, 50$) (Ace; NY1955, wpps 160, 25$) Creatures of the Abyss — Berkeley: NY, Atmosphere—ARG 1/26/18 1961, wpps 143, 35$; Sidgwick & Jackson: Attention Saint Patrick—ASF 1 /60 London.