Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Improvisational Theater in Poland and the United States

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS LODZIENSIS FOLIA LITTERARIA POLONICA 2(40) 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1505-9057.40.05 Magdalena Szuster* “Alchemy and smoke in a bottle” – contemporary improvisational theater in Poland and the United States Part 1: (Re)defining Improvised Theater – the American and Polish Perspectives What Does Impro(v) Mean Anyway? The origins of improvisation are indistinct, and for most part untraceable. An academic endeavor to establish its beginnings would go unrewarded, as there is no one distinct inventor1 of improvisation. This technique, or method, had been used as means of expression in art long before Spolin or Johnstone, and far away from Chicago or London. The Atellan farce (1 BC), secular entertainers and court jesters in China (10 BC), or the frenzied improvisations in Ancient Greece (600 BC) had preceded the 16th century commedia dell’arte2 the Italian improvised per- formance based on scenarios and/or sketches. The renaissance of improvisation in the 20th century was largely brought about by experimental artists who used it as means of expression, communication and representation. As a tool, a vessel or foundation improvisation existed in theater (both formal and popular), painting, poetry and music. It was an important substance, and an interesting addition to avant-garde art. The early avant-garde theater welcomed improvisation as a means in the pro- cess of developing plays and productions, or as a component of actor training, yet an independent improvisational format was yet to be devised. In the mid-twentieth * Dr, University of Łódź, Faculty of Philology, Department of American Literature and Cul- ture, 91-404 Łódź, ul. -

Communication and the Art of Improvisation by Jeffrey D

Communication and the Art of Improvisation BY Jeffrey D. Arterburn Submitted to the graduate degree program in Communication Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Donn Parson ________________________________ Dr. Nancy Baym ________________________________ Dr. Dave Tell Date Defended: June 19, 2012 ii The Thesis Committee for Jeffrey D. Arterburn certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Communication and the Art of Improvisation ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Donn Parson Date Approved: June 20, 2012 iii ABSTRACT Over the last 15 years, improvisational theater has been increasingly applied in organizational contexts to improve the communicative environment of that organization. It is widely held that improv benefits the communicative environment, but the reasons for its effectiveness are illusive in the literature. This study seeks to better understand the reasons for its effectiveness in application in extra-theatrical application. It does this through analyzing significant improv texts and interviews conducted by the author with several highly experienced improvisers in Chicago, the birthplace of modern improv. Through thematic analysis, nine significant topoi were established that provide understanding for what is happening when people engage in improv. Ultimately it was found that when all the topoi are combined in practice improv serves as a communicative method designed for spontaneously solving problems as they arise. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the following individuals for their counsel, advice, encouragement and support throughout the process of the creation of this project: First, I’d like to thank Dr. -

Funny Feminism: Reading the Texts and Performances of Viola

FUNNY FEMINISM: READING THE TEXTS AND PERFORMANCES OF VIOLA SPOLIN, TINA FEY AND AMY POEHLER, AND AMY SCHUMER A Thesis by LYDIA KATHLEEN ABELL Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, James Ball Kristan Poirot Head of Department, Donnalee Dox May 2016 Major Subject: Performance Studies Copyright 2016 Lydia Kathleen Abell ABSTRACT This study examines the feminism of Viola Spolin, Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, and Amy Schumer, all of whom, in some capacity, are involved in the contemporary practice and performance of feminist comedy. Using various feminist texts as tools, the author contextually and theoretically situates the women within particular feminist ideologies, reading their texts, representations, and performances as nuanced feminist assertions. Building upon her own experiences and sensations of being a fan, the author theorizes these comedic practitioners in relation to their audiences, their fans, influencing the ways in which young feminist relate to themselves, each other, their mentors, and their role models. Their articulations, in other words, affect the ways feminism is contemporarily conceived, and sometimes, humorously and contentiously advocated. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would briefly like to thank my family, especially my mother for her unwavering support during this difficult and stressful process. Her encouragement and happiness, as always, makes everything worth doing. I would also like to thank Paul Mindup for allowing me to talk through my entire thesis with him over the phone; somehow you listening diligently and silently on the other end of the line helped everything fall into place. -

Boley to Welcome

FREEANDFREAKYSINCE | AUGUST FREEANDFREAKYSINCE | AUGUST Welcome to Boley A Chicago writer explores his family’s ties to a historic Oklahoma town. By EFM| THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | AUGUST | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE TR - Mylesspentyearsinprison isolationcommunityandborders Ourcriticsreviewreleasesthatyou @ onlytobereleasedintoaworldin canenjoyathome lockdownHe’shappierthanhe’s 35 EarlyWarningsRescheduled PTB beeninalongtime concertsandotherupdatedlistings ECS K KH 35 GossipWolfRapperproducer CLR H MontanaMacksdropsacollection MEP M TDKR ofsoulfulinstrumentalsAnniRossi CEBW putsoutaplayfulvideomixtape AEJL andartsnonprofi tQuietPterodactyl SWMD LG DI BJ MS releasesanallstarcompilationto EAS N L CITYLIFE benefi tChicagomusicvenues GD AH 03 SightseeingChicagoattheturn L CSC-J CEBN B ofthecenturythroughtheeyesof L C M DLCMC RudolphFMichaelis FILM J F S F JH I 25 Review AMostBeautifulThing H C MJ MKSK FOOD &DRINK 12 BlackHistoryForgenerationshis reunitesthefi rstallBlackhigh ND L JL 04 FeatureJasmineShethis familyhasownedapieceofuntold schoolrowingteam MMAM -K Chicago’sfi rstdabbawala BlackhistoryinBoleyOklahoma 26 SmallScreenMattDamon J R N JN M O M S CS Thisyearhefi nallygottoseeit Improv’snewwebseriesisfi lled ---------------------------------------------------------------- withZoommeetingdisastersand DD J D ARTS&CULTURE personalmassagertriumphs SMCJ G 16 ComedyRememberingiO’s 27 MoviesofNoteSheDies SSP humblebeginningsandrefl ectingon Tomorrowisaworthyexamination OPINION ATA itsdramaticend ofacollectiveunravelling 36 -

Second Serving

Paseo Herencia Thursday January 14, 2021 T: 582-7800 www.arubatoday.com facebook.com/arubatoday instagram.com/arubatoday Page 9 Aruba’s ONLY English newspaper SECOND SERVING House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of Calif., displays the signed article of impeachment against President Donald Trump in an engrossment ceremony before transmission to the Senate for trial on Capitol Hill, in Washington, Wednesday, Jan. 13, 2021. Associated Press Page 2 A2 THURSDAY 14 JANUARY 2021 UP FRONT Trump impeached after Capitol riot in historic second charge By LISA MASCARO, Democrat Joe Biden's in- MARY CLARE JALONICK, auguration Jan. 20. JONATHAN LEMIRE and Trump is the only U.S. ALAN FRAM president to be twice im- Associated Press peached. It was the most WASHINGTON (AP) — Presi- bipartisan presidential im- dent Donald Trump was im- peachment in modern peached by the U.S. House times, more so than against for a historic second time Bill Clinton in 1998. Wednesday, charged with The Capitol insurrection "incitement of insurrection" stunned and angered law- over the deadly mob siege makers, who were sent of the Capitol in a swift and scrambling for safety as the stunning collapse of his fi- mob descended, and it re- nal days in office. vealed the fragility of the With the Capitol secured nation's history of peace- by armed National Guard ful transfers of power. The troops inside and out, the riot also forced a reckoning House voted 232-197 to among some Republicans, impeach Trump. The pro- who have stood by Trump In this image from video, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Ky., speaks as the Senate ceedings moved at light- throughout his presidency reconvenes after protesters stormed into the U.S. -

Improv Nerd with Jimmy Carrane Welcomes Special Guest Charna Halpern at Four Star Comedy Fest at Navy Pier

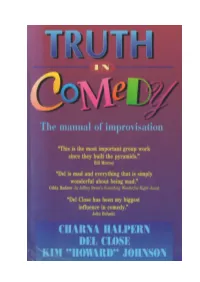

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: September 24, 2012 Nick Shields, Navy Pier 312-595-5136 [email protected] Lauren M. Heist 847-868-3653 [email protected] Improv Nerd with Jimmy Carrane welcomes special guest Charna Halpern at Four Star Comedy Fest at Navy Pier CHICAGO — Navy Pier, Inc. is excited to announce that iO Chicago founder Charna Halpern will be the guest of honor at a special performance of Improv Nerd at the inaugural Four Star Comedy Fest at Navy Pier! On Saturday, Oct. 6 at 5 p.m., host Jimmy Carrane will interview Halpern about her legendary life during a live taping of Improv Nerd, a popular podcast that gives audiences a behind-the-scenes look at careers in comedy. Tickets to Improv Nerd are free. Born in 1952, Halpern co-founded the iO with Del Close in 1984 and has launched the careers of such famous comedians as Mike Myers, Chris Farley, David Koechner, Adam McKay, Tina Fey and many more. She is the co-author of Truth in Comedy and the author of Group Improvisation and Art by Committee. “Charna is one of the most important figures in comedy today, and I think audiences are going to be fascinated with the anecdotes and history she’ll be able to give about so many celebrities,” Carrane says. “It’s going to be a great show!” The live Improv Nerd taping is just one of many events taking place on Oct. 6 as part of the Four Star Comedy Fest. From 1 p.m. – 4 p.m., attendees will have the chance to participate in free workshops for the entire family taught by some of Chicago’s most well-respected improv training centers including The Annoyance Theater, ComedySportz and iO. -

Jay Sukow Jay Sukow

Jay Sukow Jay Sukow 14836 Dickens Street #12 | Sherman Oaks, CA 91403 | 312.699.2206 | [email protected] | www.todayimprov.com Stage The Best of the Second City Northwest ensemble The Second City NW Watch your Back ensemble The Second City NW Mitch Greene Presents... Mitch Greene Various Various improv and sketch comedy groups Guest Artist Second City Mainstage, Second City ETC, Second City Northwest, Messing with a Friend, Boom Chicago, ComedySportz (various) Film American Legacy Dale Harris Group Mind Films Trubadeaux: A Restaurant Movie Gavin Brandt Group Mind Films Direction Sheboygan Director Chicago Sketch Fest Web Bye Dr. Johnson Fulton Market Films Numerous corporate live and video productions. List available upon request. Training Improvisation • Del Close, Charna Halpern, Kevin Dorff, Jon Favreau, TJ Jagodowski, Peter Gwinn, Noah Gregoropolous at iO Chicago • Stephen Colbert, Steve Carell, David Razowsky, Michael Gellman, Tom Gianis, Fran Adams at The Second City • Keith Johnstone, Dick Schaal • Mick Napier, Mark Sutton, Rebecca Sohn at the Annoyance Theater Acting • Meisner: Sommer Austin and Andrew Gallant • Scene Study: Marlene Zuccaro Degree • BA in Mass Communications, Illinois State University, 1992 Festivals New Orleans Improv Festival (instructor and performer), C/U Improv Fest (instructor and performer), Del Close Marathon (performer), CIF Teen Comedy Festival (instructor), CIF apprentice team (instructor) Other Sketch writing (both theatrically and corporate), juggling, sports expertise, loves Beastie Boys, eyes change color based on what I’m wearing.. -

Truth in Comedy.Pdf

Meriwether Publishing Ltd., Publisher P.O. Box 7710 Colorado Springs, CO 80933 Editor: Arthur L. Zapel Typesetting: Sharon E. Garlock Cover design: Tom Myers © Copyright MCMXCIV Meriwether Publishing Ltd. Printed in the United States of America First Edition All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission of the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Halpern, Charna, 1952- Truth in Comedy : the manual for improvisation / by Charna Halpern, Del Close, and Kim "Howard" Johnson. - 1st ed. p. cm. ISBN 1-56608-003-7 1. Improvisation (Acting) 2. Stand-up comedy. I. Close, Del, 1934-1999. II. Johnson, Kim, 1955- . III. Title. PN2071.I5H26 1993 792\028-dc20 93-43701 CIP 6 7 8 01 02 03 04 DEDICATIONS Charna Halpern To my loving parents, Jack and Iris Halpern. Without their constant calls to push me to continue writing, this book might never have been finished. I also thank them for raising me in a home that was always filled with laughter. and to Rick Roman — wherever you are. Del Close To Severn Darden, Elaine May and Theodore J. Flicker. Kim "Howard" Johnson To Laurie Bradach, who improvises with me every day, and for the Baron's Barracudas, who blazed the trail. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS So many have been so wonderful. I'd like to send my thanks — To Bill Murray, Mike Myers, George Wendt, Chris Farley, Andy Richter, and Andy Dick for their support — To Suzanne Plunkett, the best photographer in Chicago — To Thorn Bishop for his way with words — To David Shepherd, Paul Sills, and Bill Williams for their inspiration — To Betsy Nolan for being a perfectionist — To "The Family" and all the other ImprovOlympic teams, for helping us to learn from them — Special thanks to Kim Yale — TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by Mike Myers …………………………………………………. -

ERIC HUNICUTT Director | Actor | Improv Specialist | Arts Educator & Administrator CURRICULUM VITAE

ERIC HUNICUTT Director | Actor | Improv Specialist | Arts Educator & Administrator CURRICULUM VITAE HIGHER EDUCATION BACHELOR OF ARTS COMMUNICATIONS – MEDIA STUDIES / PRODUCTION The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill NC Graduate with Highest Distinction; Dean’s List; GPA 3.8 CAROLINA BUSINESS INSTITUTE University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill NC ADDITIONAL PROFESSSIONAL TRAINING GOB SQUAD San Diego CA / 2017 ALAN ALDA CENTER FOR COMMUNICATING SCIENCE Stony Brook University NY / 2016 AK STUDIOS Los Angeles / 2012 – 2015 LINCOLN CENTER THEATER DIRECTORS LAB New York / 2013 WARNER LOUGHLIN STUDIOS Los Angeles / 2009 – 2010 STEPPENWOLF CLASSES WEST Los Angeles / 2006 – 2008 IMPROV OLYMPIC (IO) WEST THEATER Los Angeles / 2005 – 2007 IMPROV OLYMPIC (iO) THEATER Chicago / 1999-2005 THE SECOND CITY CONSERVATORY Chicago / 1999 – 2001 COMEDY SPORTZ THEATER Raleigh, NC / 1992 -1999 HONORS Phi Beta Kappa; Golden Key Honor Society; Dean’s List ADMINISTRATIVE & MANAGEMENT EXPERIENCE Producer & Managing Director Steppenwolf Classes West Summer Intensive / 2016 – Present Administrator, Media & Website Coordinator Steppenwolf Classes West / 2009 – Present Director of Training / Managing Director / Bookkeeper Improv Olympic West Theatre & Training Center, Los Angeles / 2005 – 2009 Producer Los Angeles Improv Comedy Festival / 2005 – 2009 ACADEMIC TEACHING EXPERIENCE Instructor, Graduate Division / 2016 - Present University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA • Teach science communication techniques to undergraduate, graduate, post-docs, researchers -

And the Story of Grace, Wit & Charm

DIKULT 350—Mastergradsoppgåve i digital kultur Networked Improv Narrative (Netprov) and the Story of Grace, Wit & Charm By Rob Wittig A Thesis Prepared for the Master’s Degree in Digital Culture Institutt for lingvistiske, litterære og estetiske studier Universitetet i Bergen Autumn, 2011 / Høst 2011 1 0_Abstract Netprov (networked improv narrative) is an emerging art form that creates written stories that are networked, collaborative and improvised in real time. What optimum characteristics could give netprov projects—playful as they are—the depth of the great novels of the past? This question is explored through research and through a practical project, an original netprov—Grace, Wit & Charm —created, performed and documented in May of 2011 by the author for this thesis. Part 1 first defines netprov and lists its characteristics. Then it examines, historically and critically, the five tributary fields of netprov: 1) networked games (particularly Alternate Reality Games), 2) theater (particularly improvisation), 3) mass media (including notions of transmedia and phenomenon of fan fiction), 4) literature (particularly the fictionalization of vernacular forms used for telling truth), and 5) the Internet, social media and personal media (where the fictionalization of vernacular forms is pervasive). Best practices are drawn from each field. Netprov is understood as creative game based on the progression: mimicry, parody, satire. Part 2 examines Grace, Wit & Charm's form, process and fictional subject matter and evaluates the May 2011 collaborative performance using the characteristics and best practices from Part One as a rubric. Grace, Wit & Charm concerns a fictional company that improves its clients’ online self-presentation, providing GraceTM for clumsy avatars, WitTM for the humorless, and CharmTM for the romantically impaired. -

Improvisation for the Mind: Theatrical Improvisation, Consciousness, and Cognition

Improvisation for the Mind: Theatrical Improvisation, Consciousness, and Cognition A dissertation submitted by Clayton Deaver Drinko In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama Tufts University May 2012 © 2012, Clayton D. Drinko Advisor: Downing Cless ii Abstract Improvisation teachers Viola Spolin, Del Close, and Keith Johnstone knew that with structure and guidelines, the human mind can be trained to be effortlessly spontaneous and intuitive. Cognitive studies is just now catching up with what improvisers have known for over fifty years. Through archival research, workshops, and interviews, I ask what these improvisation teachers already knew about improvisation’s effects on consciousness and cognition. I then hold their theories up against current findings in cognitive neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy. The hypothesis that comes out of my methodology is that improvisation orders consciousness. By demanding an outward focus on other improvisers and the game being played, improvisation diminishes one’s internal focus. This reduces self-consciousness, fear, and anxiety. I also look at more extreme examples of this change in focus where improvisers reach states of flow and experience changes in perception, time, and memory. Examining cognitive studies’ relevance to improvisation has implication for scripted productions, therapy, and our everyday lives. The guidelines of improvisation and how those guidelines alter consciousness and cognition can serve as a model in ordering consciousness, interacting with people, and living optimally. iii Acknowledgements I have to thank my advisor, Downing Cless. Thank you for stepping up to the plate, giving me great revision ideas, and challenging me to make this dissertation stronger, better, and faster. -

1 of 1 HISTORY of IMPROVISATION Edited and Summarized by Walt Frasier

EIGHT IS NEVER ENOUGH STUDY GUIDE 1 of 1 HISTORY of IMPROVISATION Edited and summarized by Walt Frasier. Go to http://en.wikipedia.org/ to discover more amazing information on the following companies and key figures in Improvisation Theater History. Viola Spolin was an American drama teacher and author. She is considered by many to be the American Grandmother of Improvisation. Author of “Improvisation for the theater” still respected as one of the best books on the subject. Paul Sills was a director and improvisation teacher, and the original director of The Second City, Playwrights and Compass Players. Paul was the son of teacher and writer Viola Spolin. Mike Nichols (born 6 November 1931) is one of America’s most imprortant television, stage and film director, writer, and producers. Nichols is one of the few people to have won all the major American entertainment awards: an Oscar, Grammy, Emmy and Tony Award. Started as an Improv Actor/Comedian. Toured with Elain May in the popular team act “Nichols & May”. Recently directed SPAMALOT on Broadway. Del Close is considered one of the premier influences on modern improvisational theater. An actor, improviser, writer, and teacher, Close had a prolific career, appearing in a number of films and television shows. He was a co-author of the book Truth in Comedy along with partner Charna Halpern, which outlines techniques now common to longform improvisational theater and describes the overall structure of “Harold” which remains a common frame for longer improvisational scenes. The Compass Players (or Compass Theater) was a 1950s cabaret revue show started by alumni from the University of Chicago.[1].