Simplification of the Arabic Script: Three Different Approaches and Their Implementations Yannis Haralambous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

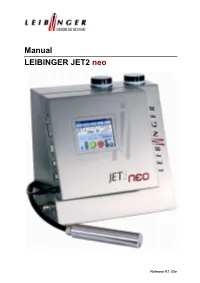

Manual LEIBINGER JET2 Neo

Manual LEIBINGER JET2 neo Release R1.00e Group 1 Table of contents Page 1 1.1 Table of contents 1.1 Table of contents ..........................................................................................................1 1.2 Group directory.............................................................................................................9 1.3 Publisher.....................................................................................................................10 1.4 Introduction.................................................................................................................12 1.5 Document information.................................................................................................13 1.6 Guarantee...................................................................................................................13 2. Safety ..............................................................................................................................14 2.1 Dangers......................................................................................................................14 2.2 Safety instructions and recommendations...................................................................14 2.3 Intended use...............................................................................................................16 2.4 Safety sticker ..............................................................................................................17 2.5 Operating staff ............................................................................................................18 -

The Origin of the Peculiarities of the Vietnamese Alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt

The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt To cite this version: André-Georges Haudricourt. The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet. Mon-Khmer Studies, 2010, 39, pp.89-104. halshs-00918824v2 HAL Id: halshs-00918824 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00918824v2 Submitted on 17 Dec 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Published in Mon-Khmer Studies 39. 89–104 (2010). The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet by André-Georges Haudricourt Translated by Alexis Michaud, LACITO-CNRS, France Originally published as: L’origine des particularités de l’alphabet vietnamien, Dân Việt Nam 3:61-68, 1949. Translator’s foreword André-Georges Haudricourt’s contribution to Southeast Asian studies is internationally acknowledged, witness the Haudricourt Festschrift (Suriya, Thomas and Suwilai 1985). However, many of Haudricourt’s works are not yet available to the English-reading public. A volume of the most important papers by André-Georges Haudricourt, translated by an international team of specialists, is currently in preparation. Its aim is to share with the English- speaking academic community Haudricourt’s seminal publications, many of which address issues in Southeast Asian languages, linguistics and social anthropology. -

Daniel O'connell

Daniel O’Connell 708 Hoover St., Norman OK 73072 (405) 820-6218 – [email protected] EDUCATION ACCELERATED DUAL DEGREE PROGRAM: Completing Petroleum Engineering undergraduate Degree and an MBA concurrently Michael F. Price College of Business, University of Oklahoma Norman, OK Master of Business Administration; GPA: 4.0/4.0 May 2018 Training the Street; Two-Day Financial Modeling Seminar Mewbourne College of Earth and Energy, University of Oklahoma Norman, OK Bachelor of Science in Petroleum Engineering; GPA: 3.4/4.0 May 2018 EXPERIENCE May 2017- Gulfport Energy Oklahoma City, OK August 2017 Reservoir Engineering, (Internship) Forecasted oil, gas, and water production and revenues for all PDP wells within ARIES Quantified the effect of compression and spacing on already producing wells Created a water type-curve lookup table within ARIES, based on correlations found in Spotfire, to be used in water production forecasting for new wells drilled in the Utica January 2017- OU Center for Creation of Economic Wealth (CCEW) Norman, OK May 2017 Oklahoma Funding Accelerator Consulting Associate (Internship) Semester-long internship working closely with local Oklahoma City startup, SendARide, on business model generation, business plan creation, financial projections, and loan proposal preparation Researched and suggested top priority candidates for adoption of the SendARide app Explored healthcare regulations for possible limitations and opportunities for success May 2016- LINN Energy Agua Dulce, TX August 2016 Production Engineering, -

CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotyping in Psychiatry

CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotyping in psychiatry Citation for published version (APA): Koopmans, A. B. (2021). CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotyping in psychiatry: bridging the gap between practice and lab. ProefschriftMaken. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20210512ak Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2021 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20210512ak Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim

Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim To cite this version: Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim. Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space. Tenth International Workshop on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition, Université de Rennes 1, Oct 2006, La Baule (France). inria-00105116 HAL Id: inria-00105116 https://hal.inria.fr/inria-00105116 Submitted on 10 Oct 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim Jin Hyung Kim Artificial Intelligence and Artificial Intelligence and Pattern Recognition Lab. Pattern Recognition Lab. KAIST, Daejeon, KAIST, Daejeon, South Korea South Korea [email protected] [email protected] Abstract defined shape of character while it showed high recognition performance. Moreover when a user writes In this work, we propose a 3D space handwriting multiple stroke character such as ‘4’, the user has to recognition system by combining 2D space handwriting write a new shape which is predefined in a uni-stroke models and 3D space ligature models based on that the and which he/she has never seen. -

ISO Basic Latin Alphabet

ISO basic Latin alphabet The ISO basic Latin alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet and consists of two sets of 26 letters, codified in[1] various national and international standards and used widely in international communication. The two sets contain the following 26 letters each:[1][2] ISO basic Latin alphabet Uppercase Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z alphabet Lowercase Latin a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z alphabet Contents History Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters Names for the two subsets Names for the letters Timeline for encoding standards Timeline for widely used computer codes supporting the alphabet Representation Usage Alphabets containing the same set of letters Column numbering See also References History By the 1960s it became apparent to thecomputer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin script in their (ISO/IEC 646) 7-bit character-encoding standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. The standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 8859 (8-bit character encoding) and ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin script with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.[1] Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters The Unicode block that contains the alphabet is called "C0 Controls and Basic Latin". -

Arabic Alphabet - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Arabic Alphabet from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

2/14/13 Arabic alphabet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Arabic alphabet From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia َأﺑْ َﺠ ِﺪﯾﱠﺔ َﻋ َﺮﺑِﯿﱠﺔ :The Arabic alphabet (Arabic ’abjadiyyah ‘arabiyyah) or Arabic abjad is Arabic abjad the Arabic script as it is codified for writing the Arabic language. It is written from right to left, in a cursive style, and includes 28 letters. Because letters usually[1] stand for consonants, it is classified as an abjad. Type Abjad Languages Arabic Time 400 to the present period Parent Proto-Sinaitic systems Phoenician Aramaic Syriac Nabataean Arabic abjad Child N'Ko alphabet systems ISO 15924 Arab, 160 Direction Right-to-left Unicode Arabic alias Unicode U+0600 to U+06FF range (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0600.pdf) U+0750 to U+077F (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0750.pdf) U+08A0 to U+08FF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U08A0.pdf) U+FB50 to U+FDFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UFB50.pdf) U+FE70 to U+FEFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UFE70.pdf) U+1EE00 to U+1EEFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1EE00.pdf) Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols. Arabic alphabet ا ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arabic_alphabet 1/20 2/14/13 Arabic alphabet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia غ ف ق ك ل م ن ه و ي History · Transliteration ء Diacritics · Hamza Numerals · Numeration V · T · E (//en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Template:Arabic_alphabet&action=edit) Contents 1 Consonants 1.1 Alphabetical order 1.2 Letter forms 1.2.1 Table of basic letters 1.2.2 Further notes -

Writing Systems Reading and Spelling

Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems LING 200: Introduction to the Study of Language Hadas Kotek February 2016 Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Outline 1 Writing systems 2 Reading and spelling Spelling How we read Slides credit: David Pesetsky, Richard Sproat, Janice Fon Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems What is writing? Writing is not language, but merely a way of recording language by visible marks. –Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and speech Until the 1800s, writing, not spoken language, was what linguists studied. Speech was often ignored. However, writing is secondary to spoken language in at least 3 ways: Children naturally acquire language without being taught, independently of intelligence or education levels. µ Many people struggle to learn to read. All human groups ever encountered possess spoken language. All are equal; no language is more “sophisticated” or “expressive” than others. µ Many languages have no written form. Humans have probably been speaking for as long as there have been anatomically modern Homo Sapiens in the world. µ Writing is a much younger phenomenon. Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems (Possibly) Independent Inventions of Writing Sumeria: ca. 3,200 BC Egypt: ca. 3,200 BC Indus Valley: ca. 2,500 BC China: ca. 1,500 BC Central America: ca. 250 BC (Olmecs, Mayans, Zapotecs) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and pictures Let’s define the distinction between pictures and true writing. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

GAF Timberline Series Application Instructions

Application Instructions Timberline® HDTM, Timberline® Natural ShadowTM, Timberline® Ultra HDTM, Timberline® Cool Series, Timberline® American HarvestTM, Updated: 4/12 Quality You Can Trust… From North America’s Largest Roofing Manufacturer!™ www.gaf.com Quality You Can Trust…From North America’s Largest Roofing Manufacturer!™ ¡Calidad En La Que Usted Puede Confiar...Del Fabricante De Techos Más Grande De Norteamérica!™ Une Qualité À Laquelle Vous Pouvez Vous Fier... Du Plus Gros Fabricant De Toitures En Amérique Du Nord! MC INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS · INSTRUCCIONES DE INSTALACIÓN · INSTRUCTIONS D’INSTALLATION LIFETIME HIGH DEFINITION® SHINGLES LIFETIME SHINGLES TEJAS DE ALTA DEFINICIÓN® DE POR VIDA TEJAS DE POR VIDA BARDEAUX DE HAUTE DÉFINITION® À VIE BARDEAUX À VIE LIFETIME HIGH DEFINITION® SHINGLES TEJAS DE ALTA DEFINICIÓN® DE POR VIDA ENERGY-SAVING ARCHITECTURAL SHINGLES TEJAS ARQUITECTÓNICAS PARA AHORRO DE ENERGÍA BARDEAUX DE HAUTE DÉFINITION® À VIE BARDEAUX ARCHITECTURAUX ÉCONERGÉTIQUES GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS t."5&3*"-4"'&5:%"5"4)&&54 When using GAF products, e.g., shingles, underlayments, plastic cement, etc., please refer to the applicable MSDS. The most current versions are available at www.gaf.com. GAF does not provide safety data sheets or installation instructions for products not manufactured by GAF. Please consult the material manufacturer for their MSDS and installation instructions where appropriate. t300'%&$,4Use minimum 3/8" (10mm) plywood or OSB decking as recommended by APA-The Engineered Wood Assn. Wood decks must be well-seasoned and supported having a maximum 1/8" (3mm) spacing, using minimum nominal 1"(25mm) thick lumber, a maximum 6" (152mm) width, having adequate nail-holding capacity and a smooth surface. -

Writing Systems: Their Properties and Implications for Reading

Writing Systems: Their Properties and Implications for Reading Brett Kessler and Rebecca Treiman doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199324576.013.1 Draft of a chapter to appear in: The Oxford Handbook of Reading, ed. by Alexander Pollatsek and Rebecca Treiman. ISBN 9780199324576. Abstract An understanding of the nature of writing is an important foundation for studies of how people read and how they learn to read. This chapter discusses the characteristics of modern writing systems with a view toward providing that foundation. We consider both the appearance of writing systems and how they function. All writing represents the words of a language according to a set of rules. However, important properties of a language often go unrepresented in writing. Change and variation in the spoken language result in complex links to speech. Redundancies in language and writing mean that readers can often get by without taking in all of the visual information. These redundancies also mean that readers must often supplement the visual information that they do take in with knowledge about the language and about the world. Keywords: writing systems, script, alphabet, syllabary, logography, semasiography, glottography, underrepresentation, conservatism, graphotactics The goal of this chapter is to examine the characteristics of writing systems that are in use today and to consider the implications of these characteristics for how people read. As we will see, a broad understanding of writing systems and how they work can place some important constraints on our conceptualization of the nature of the reading process. It can also constrain our theories about how children learn to read and about how they should be taught to do so. -

Persian Ugs Kobo Audiobook.Pdf

LESSON NOTES Basic Bootcamp #1 Self Introductions - Basic Greetings in Persian CONTENTS 2 Persian 2 English 2 Romanization 2 Vocabulary 3 Sample Sentences 4 Vocabulary Phrase Usage 6 Grammar # 1 COPYRIGHT © 2013 INNOVATIVE LANGUAGE LEARNING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PERSIAN . : .1 . : .2 . : .3 . : .4 ENGLISH 1. BEHZAD: Hello. I'm Behzad. What's your name? 2. MARY: Hello Behzad. My name is Mary. 3. BEHZAD: Nice to meet you. 4. MARY: You too. ROMANIZATION 1. BEHZAD: Salam, man Behzad am. Esme shoma chi e? 2. MARY: Salam Behzad, Esme man Mary e. 3. BEHZAD: Az ashnayi ba shoma khoshvaght am. 4. MARY: Man ham hamintor. VOCABULARY PERSIANPOD101.COM BASIC BOOTCAMP #1 - SELF INTRODUCTIONS - BASIC GREETINGS IN PERSIAN 2 Persian Romanization English Class Man ham hamintor. me too phrase Az ashnayi ba shoma khoshvaght Nice to meet you sentence am. ... Esme man (...) e. My name is (...). sentence Esme shoma chi e? What’s your name? sentence salaam hello interjection man I, me pronoun hastam (I) am verb esm name noun SAMPLE SENTENCES : . : . . . ali: man gorosne hastam. zahraa: man ham man faateme hastam. az aashnaayi baa shomaa hamin tor. khoshvaghtam. Ali: I'm hungry. Zahra: Me too. My name is Fateme. Nice to meet you. . esm-e man zeinabe. esm-e man naaser e. esm-e shomaa chie? My name is Zeinab. My name is Naser. What is your name? . . Oo hich vaght be man salaam nemikonad. Az man aks nagir. He never says hello to me. "Don't take photos of me." . Man ta hala chenin chizi nadidam. Kheili khaste hastam I have never seen such a thing.