Reduplication Across Categories in Cantonese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Zodiac Animals Trail #Cnysunderland2021

Chinese Zodiac Animals Trail #CNYSunderland2021 Find out amazing facts about the 12 animals of the Chinese Zodiac and try some fun animal actions. 12th February 2021 is the start of the Year of the Ox, but how were the animals chosen and in which order do they follow each other? Find out more….. How did the years get their names? A long time ago in China, the gods decided that they wanted to name the years after animals. They chose twelve animals – dragon, tiger, horse, snake, pig, cockerel, rat, rabbit, goat, dog, ox and monkey. All of these wanted the first year to be named after them as they all thought themselves to be the most important. Can you imagine the noise when they were arguing? They made so much noise that they woke up the gods. After listening to all their arguments the gods decided to settle the matter by holding a race across a wide river. The years would be named according to the order in which the animals finished the race. The animals were very excited. They all believed that they would win – although the pig wasn’t quite so sure. During the race there were many changes in position, with different animals taking the lead. As they approached the river bank ox was in the lead with rat a very close second. Rat was determined to win but he was getting very tired. He had to think quickly. He managed to catch the ox’s tail and from there he climbed onto his back. Ox could see that he was winning but just as he was about to touch the bank, rat jumped over his head and landed on dry land. -

Chinese Animal Predictions for 2021. Year of the Yin Metal Ox (Xin Chou)

Chinese Animal Predictions for 2021. Year of the Yin Metal Ox (Xin Chou) What does 2021 have in store for you? © Written by Daniel Hanna October 2020 “We will open the book. Its pages are blank. We are going to put words on them ourselves. The book is called Opportunity and its first chapter is New Year's Day.” The Chinese New Year begins a new cycle of the twelve Chinese zodiac animals and in 2021, this will be the year of the Yin Metal Ox. A change in the Cycle will usually bring a fresh start for the year ahead with hope and promise for some form of success; some animals will face more challenges than others in 2021 although each of the twelve animals will be able to make this a promising year ahead once they are aware of any challenges that may come their way. Everyone in the world was faced with big challenges in 2020 and unfortunately, it is more than likely that this will continue through a lot of 2021, bringing health and financial issues to a large number of the world’s population. The year of the Ox will almost likely come with its share of challenges although it is how we handle obstacles that will define how our year will turn out; all of the twelve Chinese animals have everything in their power to overcome any challenges and make this a successful year and when aware of potential risks, they can minimise and even avoid them during the year of the Ox so please read carefully below. -

Zodiac Animal Masks

LUNAR NEW YEAR ZODIAC ANIMAL MASKS INTRODUCTION ESTIMATED TIME The Year of the Ox falls on February 12 this year. 15–20 minutes The festival is celebrated in East Asia and Southeast Asia and is also known as Chun Jié (traditional Chinese: 春節; simplified Chinese:春节 ), or the Spring MATERIALS NEEDED Festival, as it marks the arrival of the season on the lunisolar calendar. • Chart (on the next page) to find your birth year and corresponding zodiac animal The Chinese Zodiac, known as 生肖, is based on a • Zodiac animal mask templates twelve-year cycle. Each year in that cycle is correlated to an animal sign. These signs are the rat, ox, tiger, • Printer rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog, • Colored pencils, markers, crayons, and/or pens and pig. It is calculated according to the Chinese Lunar • Scissors calendar. It is believed that a person’s zodiac animal offers insights about their personality, and the events • Hole punch in his or her life may be correlated to the supposed • String influence of the person’s particular position in the twelve-year zodiac cycle. Use the directions below to teach your little ones STEPS how to create their own paper zodiac animal mask to 1. Using the Chinese zodiac chart on the next page, celebrate the Year of the Ox! find your birth year and correlating zodiac animal. 2. Print out the mask template of your zodiac animal. 3. Color your mask, cut it out, and use a hole punch and string to make it wearable. CHINESE ZODIAC CHART LUNAR NEW YEAR CHINESE ZODIAC YEAR OF THE RAT YEAR OF THE OX YEAR OF THE TIGER 1972 • 1984 • 1996 • 2008 1973 • 1985 • 1997 • 2009 1974 • 1986 • 1998 • 2010 Rat people are very popular. -

Glossary of Some Divination-Related Terms

1 GLOSSARY OF SOME DIVINATION-RELATED TERMS Richard J. Smith Rice University 1-13-12 NOTE: The six online glossaries for Fathoming the Cosmos and Ordering the World: The Yijing (I- Ching, or Classic of Changes) and Its Evolution in China (more than sixty single-spaced pages in all) can be found at: http://history.rice.edu/Yijing. They are: A. Names (People, Places, etc.) B. Titles (Books, Chapters, etc.) C. Terms and Expressions D. Hexagram Glossary (Alphabetical) E. Hexagram Glossary (Received Text Order) F. Mawangdui Hexagram Glossary (Alphabetical) SOME BASIC DIVINATION-RELATED TERMS [Cf. the translated terms in Bent Nielsen’s A Companion to Yi jing Numerology and Cosmology: Chinese Studies of Images and Numbers from Han 202 BCE–220 CE) to Song (960–1279 CE), which is organized by Pinyin transliterations. The page numbers in brackets following the items in the “Translation(s)” column refer to Nielsen’s indispensible work.] Pinyin Wade-Giles Chinese Translation(s)* Bagong Pa-kung 八宮 Eight palaces [pp.1-6] Bagua Pa-kua 八卦 Eight trigrams [pp. 6-7] Bazi Pa-tzu 八字 Eight [natal] characters Beijiao Pei-chiao 杯珓 Divining Blocks Bu Pu 卜 Divine Bingzhan Ping-chan 兵占 Military divination Bushi Pu-shih 卜筮 Divination by milfoil (see shi) Cezi Ts’e-tzu 測字 Fathoming characters Chaizi Ch’ai-tzu 拆字 Dissecting characters Dao Tao 道 [The] Way [pp. 45-46] Di Ti 帝 Lord [on High]; Emperor Di Ti 地 Earth [p. 48] Chunniu Ch’un-niu 春牛 Spring Ox Dizhi Ti-chih 地支 Earthly branches Dunjia Tun-chia 遁甲 Evasive Techniques (aka Qimen Dunjia) Fangji Fang-chi 方技 Technicians Fangshi Fang-shih 方士 Masters of the occult Fangshu Fang-shu 方術 Predictive and prescriptive arts Feifu Fei-fu 飛伏 Flying and hidden lines/trigrams [pp. -

Strong and Weak Dialects of China: How Cantonese Succeeded Whereas Shaan'xi Failed with the Help of Media

Asian Social Science; Vol. 10, No. 15; 2014 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Strong and Weak Dialects of China: How Cantonese Succeeded Whereas Shaan’Xi Failed with the Help of Media Mao Yu-Han1 & Hugo Yu-Hsiu Lee1 1 Graduate School of Language and Communication, National Institute of Development Administration, Thailand Correspondence: Hugo Yu-Hsiu Lee, Graduate School of Language and Communication, National Institute of Development Administration, Bangkok, Thailand. Tel: 88-607-2560. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 5, 2014 Accepted: June 4, 2014 Online Published: July 11, 2014 doi:10.5539/ass.v10n15p23 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n15p23 Abstract This research addresses an important set of social scientific issues—how language maintenance between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech—also known as dialects—are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries that are created by them and accompany them. In particular, it examines how the television series and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over the other. The value of this thesis is ultimately judged by its contribution to the sociolinguistic literature. All of these issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature—a sub-branch of sociolinguistics—particularly with respect to the language maintenance literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. -

Lunar New Year's Celebrations, Traditions, and Superstitions

Lunar New Year's Celebrations, Traditions, and Superstitions This holiday season also includes celebrating Lunar New Year. For many families in the United States and in several Asian countries, this special time of year brings family and friends together. The Lunar New Year, most commonly associated with the Chinese New Year or Spring Festival, typically falls sometime between late January and mid February on the Gregarian calendar. In 2021, the Lunar New Year is on February 12, and it's the Year of the Metal Ox. It is called the Lunar New Year because it marks the first new moon of the lunisolar calendars that are traditional to many East Asian countries, including China and Vietnam, which are regulated by the cycles of the moon and sun. In China, the Lunar New Year celebration kicks off on New Year's Eve with a family feast called a “reunion dinner,” which is full of traditional Lunar New Year foods. During the 15-day celebration starting with January 1 of the lunisolar calendar, a symbolic ritual will take place. The ritual varies somewhat from region to region, and ranges from appealing to the deities to paying respect to the ancestors. Then, the welcoming of the New Year or Spring Festival culminates on January 15 of the lunisolar calendar with the Lantern Festival, and eating of dumplings in the North and sticky rice balls in the South. The Lunar New Year isn't only observed in China. It is also celebrated across several countries and other territories in Asia, including South Korea and Singapore. -

Lunar New Year - 2021

Lunar New Year - 2021 Year of the Ox The Lunar New Year isn't only observed in China, it's celebrated across several countries and other territories in Asia, including South Korea, Vietnam, Tibet and Singapore. In the U.S., it is most commonly associated with what is often called Chinese New Year, an American version of China's 15- day-long festivities. It's called the Lunar New Year because it marks the first new moon of the lunisolar calendars traditional to many east Asian countries which are regulated by the cycles of the moon and sun. Spring Festival, Lunar • “Jiu Niang Tang” – sweet Traditions of Lunar New Years New Year or Chinese wine-rice soup Attracting and carrying over good fortune into the next • New Year? Dumplings symbolize year is a major theme of the holiday, and so is protecting wealth against bad fortune. Chinese New Year • Long Noodles represent Spring Festival longevity • Dances: The Dragon Dance features visible chunjie (春节) puppeteers holding poles as they make the dragon move in a flowing motion. A Lion Dance typically Things to Do and Not Do Korean New Year features two performers inside the costume, Seolla Do: operating as the creature's front and back legs. It's supposed to send away any evil spirits. It's an Vietnamese New Year • Only talk about good, happy things opportunity to feed the lion with red envelopes. While Tết nguyên Đán these two dances are among the best known, • Pay back your debts before Taiwaneses New Year the new year starts or it is Maasbach says they're just a few examples native to Spring Festival bad luck. -

The Chinese Zodiac Follows a Cycle of 12 Years. Each Year Is Represented

The Chinese zodiac follows a cycle of 12 years. Each year is represented by a real or mythical animal, whose characteristics determine the personality and fate of every person born that year. According to ancient Chinese legend, many centuries ago the Jade Emperor called all the animals of the kingdom to him. Only twelve obedient animals respond- ed to his call, so the Jade Emperor decided to reward them for listening. He assigned each of the animals to one of the twelve lunar years. “But which order would the ani- mals be in?,” he thought. To solve this problem, he decided to hold a race to see which of the animals would reach the other side of the river first. The animals would receive their place in the twelve lunar years according to the order they reached the finish line. The ox was worried about the race because he was nearly blind, and the rat was worried that he was too small compared to the other animals. So the ox made a deal with the rat: the rat would ride on the ox’s back and act as his guide. That way, the ox would be able to “see” and the rat would be “faster.” Then the race started. All the animals gathered at one side of the river’s bank and jumped in. As the ox pulled ahead of all the animals and was about to reach the finish line, the rat jumped off the ox’s back and reached the opposite side of the bank first. Therefore, the rat became the first animal in the zodiac, followed by the ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog, and boar. -

LOSAR-Prayers-4Feb21

TIBETAN NEW YEAR - YEAR OF THE IRON OX LOSAR PRAYERS FEB. 12, 2021 REFUGE AND BODHICITTA SANG GYE CHÖ DANG TSOK KYI CHOK NAM LA CHANG CHUP BARDU DAK NI KYAP SU CHI DAK GI JIN SOK GYI PE SONAM KYI DRO LA PHAN CHIR SANGYE DRUP PAR SHOK In the Buddha, the Dharma, and the NoBle Sangha I take Refuge until Enlightenment is fully realized. By the merit accumulated through the practice of generosity and the Six Paramitas, May I become enlightened for the benefit of all beings. FOUR IMMEASURABLES PRAYER OF BODHICITTA SEMCHAN TAMCHED DEWA DANG DEWE GYU DANG DAN PAR GYUR CHIK SEMCHAN TAMCHED DUK NGAL DANG DUK NGAL GYI GYU DANG DRALWAR GYUR CHIK SEMCHAN TAMCHED DUK NGAL MED PE DEWA DAMPA DANG MI DRALWAR GYUR CHIK SEMCHAN TAMCHED NYE RING CHAK DANG NYI DANG DRALWE TANG NYOM LA NE PAR GYUR CHIK May all beings have happiness, and the causes of happiness; May all be free from sorrow, and the causes of sorrow; May all never be separated from the sacred happiness which is sorrowless; And may all live in boundless equanimity, without aachment, and without aversion. FOUR LINES OF BODHICITTA CHANGCHUP SEMCHOK RINPOCHE MA KYE PA NAM KYE GYUR CHIK KYE PA NYAM PA MED PA DANG GONG NE GONG DU PEL PAR SHOK May the precious, supreme Bodhicia Be awakened in those for whom it has not arisen, And for those in whom it has been awakened, May it not decline but ever increase. V1 MANTRA RECITATION VAJRA GURU ཨ་ཿ&ྃ་བ་་་པ་སི0/་ྃ༔ OM AH HUNG VAJRA GURU PEMA SIDDHI HUNG TARA ཨ"་2་རེ་56་རེ་5#རེ་7་8། OM TARE TUTTARE TURE SOHA CHENREZIK ཨ་མ་ཎི་པེ་ྃ། OM MANI PEME HUNG VAJRASATTAVA ཨ་བ་ས་༔ OM VAJRA SATTVA HUNG BRIEF SANG OFFERING TO PURIFY CONTAMINATION by Mipham Rinpoche HUNG NANG TONG NAM DAK DUDTSI SANG CHOD DI NAMTOK LE JUNG DRIP DANG MI TSANG KUN DAK SAL NYOK MED CHÖ KU CHENPO’I NGANG SANG NGO KUNZANG DRIP MED LONG DU AH HUNG Through this smoke offering of amrita, the purity of appearance and emptiness, All contamination and defilement that comes about through thought, Is purified within the experience of the great dharmakaya—pure, clear and unsullied. -

The Chinese New Year

The Chinese New Year The Chinese Zodiac The Chinese calendar is a lunisolar calendar; thus, new year day is usually in late January or early February, and it is on a day with a new moon (ie: no moon). For 2021, Chinese New Year is on 12 February - Year of the Ox. No one knows when the Chinese calendar officially began, but it is generally accepted that Year One corresponds to the time when Emperor Huang Di began ruling China (equivalent to 2697 BC). Thus, 2020 (after Jan 25) corresponds to the Chinese year 4718. In Chinese astrology, the zodiac is represented by a 12-year cycle of 12 animals – these are the Rat, Ox, Snake, Horse, Rabbit, Tiger, Dragon, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, Pig, and the Sheep. Of all the animals in the world, why were these 12 chosen? There are many stories explaining this and they all share a similar theme: there was a race and the first 12 animals who arrived at the finish line were chosen. Rat is small but he is clever. He convinces Ox to give him a ride, but just as Ox approaches the finish line, Rat jumps ahead of Ox making Rat first on the list and Ox second. The Great Race There exists a story, in Chinese mythology, of a great race that decided which animals made it into the Zodiac and in what order. The Jade Emperor, the ruler of all gods within Chinese mythology, hosted the race. To finish the race and become one of 12 animals in the calendar, the animals had to cross a river. -

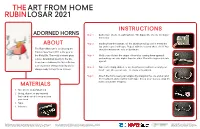

Art from Home Losar 2021

ART FROM HOME LOSAR 2021 INSTRUCTIONS ADORNED HORNS Step 1 Gather two sheets of aluminum foil. The bigger the sheets, the bigger the horns! ABOUT Step 2 Starting from the bottom, roll the aluminum foil up until it meets the top and secure it with tape. Repeat with the second sheet of foil. You The Rubin Museum is celebrating the should now have two rolls of aluminum. Tibetan New Year! 2021 is the year of the Metal Ox. The metal element gives Step 3 Mold your rolls into the shape of horns by curving them upwards a wise, determined quality to the Ox. and making one side higher than the other. Pinch the higher side into Sometimes stubborn, the Metal Ox has a point. a strong sense of responsibility and is Step 4 Take some string, ribbon, or another material and tie it around your always ready to help those in need. head—just above your ears—to create a headband. Step 5 Attach the horns near your temples by wrapping the one end around the headband and securing it with tape. (If you wear glasses, wrap the MATERIALS horns around the temples.) 1. Two sheets of aluminum foil 2. String, ribbon, or any material that can be used to wrap around your head 3. Tape 4. Scissors Family Programs are made possible through the generosity of New York Life Insurance Company*. Major General operating support of the Rubin Museum of Art is provided by the New York State Council on the *“NEW YORK LIFE” and the NEW YORK LIFE Box Logo support has also been provided by Agnes Gund, The Prospect Hill Foundation, Con Edison, Tiger Baron Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. -

Chinese Zodiac Trail

CHINESE ZODIAC TRAIL Daily 10am–6pm Fridays until 9pm Closed 24–26 December, 1 January Trafalgar Square, London WC2N 5DN www.nationalgallery.org.uk A trail exploring the symbolism of animals in Eastern and Western traditions. The Pig The Horse The Monkey The Goat The Rooster The Ox The Rabbit The Tiger The Snake The Dragon The Dog The Rat ZODIAC TRAIL CHINESE and religious teaching – how do they compare? contrasting meanings, inherited through myth, folklore In European painting, these animals have similar or animal with sign. that year’s a given year are said to have personality traits associated and each year is by represented an animal. People born in the In calendar Chinese has astrology, a 12-year cycle, 1916 1928 1940 1952 1915 1927 1939 1951 The Dragon 1964 1976 1988 2000 The Rabbit 1963 1975 1987 1999 Room 55 Room 62 Uccello: Saint George and the Dragon about 1470 Mantegna: The Agony in the Garden about 1460 The Christian story of Saint George is a classic tale of In China, people born in the year of the rabbit are graceful good triumphing over evil: a knight in shining armour and stylish. They are known for their good manners and rescues the princess from being eaten by the menacing intelligent conversation, although they can sometimes be dragon. In Christian symbolism, the dragon represents shy and over-anxious. The rabbit is also associated with the devil, and is therefore a figure of fear and destruction. the moon, since the legendary ‘Jade Rabbit’ lived in the The word comes from draco, the Latin for snake, and night sky with the goddess of the moon.