NOTES on BREEDING ACTIVITIES and on GULAR SACS in the PINE GROSBEAK by NORMAN R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brown-‐Capped Rosy Finch

Wyoming Special Mission 2013: Brown-capped Rosy Finch Information Packet >> uwyo.edu/biodiversity/birding Mission Coordinated by: Wyoming Natural Diversity Database (uwyo.edu/wyndd) Laramie Audubon Society (laramieaudubon.blogspot.com) UW Vertebrate Collection (uwyo.edu/biodiversity/vertebrate-museum) UW Biodiversity Institute (uwyo.edu/biodiversity) Wyoming Game and Fish (wgfd.wyo.gov) Page 1 Table of Contents Wanted Poster . pg. 3 Introduction to the Mission . pg. 4 Photo Guides . pg. 6 Vicinity/Trail Maps . pg. 11 Observation Form . pg. 13 Species Abstracts Brown-capped Rosy-Finch . pg. 15 Black Rosy-Finch . pg. 19 American Pika . pg. 23 Remember to bird ethically! Follow the link to read the American Birding Association’s Code of Ethics: http://www.aba.org/about/ethics.html Page 2 WANTED: Sightings of the Brown- Capped Rosy-Finch Near Medicine Bow Peak in the Snowy Mountains, WY. ACCOMPLICES: Also near Medicine Bow Peak: Black Rosy-Finch White-tailed Ptarmigan American Pika High Elevation Amphibians submit your data! Submit observations at ebird.org More information: uwyo.edu/biodiversity/birding Brown-capped rosy-finch photo courtesy of Bill Chitty Black-capped rosy-finch photo courtesy of Glen Tempke (http://www.pbase.com/gtepke/profile) White-tailed Ptarmigan photo courtesy of Flickr: USFWS Mountain Prairie Pika photo courtesy of John Whiteman Laramie Audubon UW Vertebrate Collection Toad photo courtesy of Amanda Bowe Society Wyoming Birding Special Mission 2013: Brown-capped Rosy-Finches The Issue: Various alpine-adapted species are found in very limited areas in Wyoming. The Medicine Bow Peak region in southern Wyoming is one of these areas. For one species, the Brown-capped Rosy-Finch (Leucosticte australis), the Medicine Bow peak region is the only location in Wyoming the species is known to regularly occur. -

Territory, Breeding Density, and Fall Departure in Cassin's Finch

TERRITORY, BREEDING DENSITY, AND FALL DEPARTURE IN CASSIN'S FINCH FRED B. S^•rSON WHETHERterritory during the breeding seasonacts as a mechanism to regulate breeding density or total numbers within a population of birds has aroused much interest (Hinde 1956, Wynne-Edwards 1962, Lack 1966, Brown 1969, Klomp 1972, Von Haartman 1972, Watson 1973), but controversyremains. Kluyver (1970), after studying Great Tit (Parus major) populationson the Dutch Island of Vlieland in the North Sea, indicatedthat tit numbersare regulatedin early autumn after breed- ing. In the presentinvestigation, different populationsof Cassin'sFinch (Carpodacuscassinii) were studiedduring the breedingseason and early autumn of 3 years, to determinefactors influencing breeding density and population numbers. I selectedCassin's Finch to study becauselittle is known of its breed- ing biology or postbreedingbehavior. Published descriptionsof repro- ductive activities are few, most often by residentnaturalists or those engagedin faunistic surveys (Ridgway 1877, Henshaw 1879, Grinnell 1908, Taylor 1912, Dawson 1923, Bailey 1928, Grinnell and Miller 1944• Jones and Baylot 1969), presumablybecause accessibility to montane breeding populationsis limited. Fall studies are restricted to noting numbersseen or distributionallists (Orr 1968). The breedingrange for Cassin'sFinch extendsfrom southernBritish Columbia,Alberta, and Manitoba into northernArizona and Baja Cali- fornia (Bailey and NeJdtach 1965). These authors suggestedthat Cas- sin's Finch, like the crossbill(Loxia spp.), breed whereveran abundance of food exists within their range, with specificlocations changing from year to year. For breeding, Cassin'sFinch prefers a mixed forest habitat of the alpine meadow zone generally above 1500 m (Salt 1952). Most nests are located on ends of upper branchesin tall pines (Orr 1968), and pairs may nest in coloniesor singly (Lack 1968). -

Terrestrial Habitats: Forests

Terrestrial Habitats: Grazing Lands until shortly after seedling emergence but not after early were heard. These birds were familiar across southern January. Disked corn stubble is used sporadically, primarily Minnesota where small family farms with hedgerows, in late January and February just before cranes migrate in windbreaks, and pastures provided ideal habitat until the spring. Grazed grasslands also support cranes, mostly after mid 1900s. As farms became larger with fewer hedgerows the onset of winter rains. Foraging habitat for cranes in the and pastures, the bobwhite population declined. Only a basin is currently ample, but continuing changes in small number remained in the southeastern counties by agricultural practices may result in future food shortages. 1950. Research indicates that because of a high mortality © Thomson Reuters Scientific rate and low life expectancy, up to 4000 birds may be required for a self-sustaining population. Climate also plays 829. Words from the woods: Bobwhite. a part. Bobwhites in southeastern Minnesota are on the Overcott, Nancy fringes of their northern range. The entire state may Minnesota Birding 40(6): 20-21. (2003) eventually become suitable for the species due to regional Descriptors: Colinus virginianus/ vocalization/ pastures/ warming. An increased number of bobwhite sightings in mortality/ hedgerows/ habits-behavior/ habitat use/ neighboring Houston County were observed. Wisconsin farmland/ environmental factors/ ecosystems/ distribution/ also shows an increasing trend in bobwhites numbers on climate/ census-survey methods/ birdwatching/ birds/ breeding bird surveys. The species have a tendency to bobwhite/ Minnesota: Fillmore County make seasonal movements to food sources, so it seems an Abstract: The author discusses the sighting of bobwhites expanding population of bobwhite from Wisconsin may (northern bobwhite quail) in Fillmore County, south of occasionally expand into Minnesota. -

Black Rosy-Finch Leucosticte Atrata

Wyoming Species Account Black Rosy-Finch Leucosticte atrata REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: Migratory Bird USFS R2: No special status USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: No special status State of Wyoming: Protected Bird CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: Bird of Conservation Concern WGFD: NSSU (U), Tier II WYNDD: G4, S1B/S2N Wyoming Contribution: VERY HIGH IUCN: Least Concern PIF Continental Concern Score: 16 STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS Black Rosy-Finch (Leucosticte atrata) has been assigned different S-ranks by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database for the breeding and non-breeding seasons. This is because the species’ habitat is not as restrictive during the non-breeding season, which makes the species less intrinsically vulnerable. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: There are no recognized subspecies of Black Rosy-Finch. In 1983, the three American rosy-finch species: Black Rosy-Finch, Brown-capped Rosy-Finch (L. australis), and Grey-crowned Rosy- Finch (L. tephrocotis), were combined with Asian Rosy-Finch (L. arctoa) into one species. In 1993, the American Ornithologist Union (AOU) reinstated original species status designations due to a lack of evidence supporting the merge 1. Recent genetic evidence suggests that the three North American Rosy-Finches may only constitute one species 2. However, the most recent AOU ruling rejected merging the three American rosy-finches into one species 3. Description: Identification of Black Rosy-Finch is possible in the field. The Black Rosy-Finch is approximately 16 cm in length, similar in size and overall shape to large sparrows, but stockier. The species has a mid-sized conical bill, and a relatively short, notched tail. -

Using Species Distribution Models to Quantify Climate

USING SPECIES DISTRIBUTION MODELS TO QUANTIFY CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS ON THE ROSY-FINCH SUPERSPECIES: AN ALPINE OBLIGATE by Edward C. Conrad A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Geography The University of Utah August 2015 Copyright © Edward C. Conrad 2015 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Edward C. Conrad has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Simon C. Brewer_________________ , Chair 04/16/15 Date Approved Russell E. Norvell________________ , Member 04/16/15 Date Approved Philip E. Dennison_______________ , Member 04/16/15 Date Approved and by __________________ Andrea R. Brunelle___________________ , Chair of the Department of ___________________________ Geography and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Anthropogenic climate change is forcing plants and animals to respond by shifting their distributions poleward or upward in elevation. An organism’s ability to track climate change is constrained if its habitat cannot shift and is projected to decrease in geographic extent. Geographic distributions were predicted for the Rosy-Finch superspecies (Leucosticte atrata, Leucosticte australis, Leucosticte tephrocotis) for climate change scenarios using correlative species distribution models (SDM). Multiple sources of uncertainty were quantified including choice of SDM, validation statistic, emissions scenario and general circulation model (GCM). Species distribution models are traditionally validated using a threshold-independent statistic called the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic. However, during k-fold cross-validation, this statistic becomes overinflated due to spatial sorting bias existing between the presence and background points. -

Comments on Draft List of Species of Conservation Concern

February 1, 2016 Joan Friedlander Forest Plan Revision Team Pacific Southwest Region USDA Forest Service Vallejo, CA Re: Comments on draft list of Species of Conservation Concern Dear Joan: Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the draft lists of species of conservation concern (SCC) for the Inyo (INF), Sequoia (SQF), and Sierra (SNF) national forests. We appreciate the inclusion on these draft lists of two species – sage grouse and Mt. Whitney draba (Draba sharsmithii)1 – that had been omitted from the draft lists presented in July 2015. We are, however, disappointed to see that very little of the scientific information we provided in August 2015 was incorporated into this draft list and documentation and that so few changes have been made to the draft SCC lists. In the comments below, we first raise general concerns about the approach and documentation for the determination of SCC. Second we offer comments related to the determinations for individual species. Attachment A contains additional information in support of the sections below. 1 We note that this draba was originally included on that Inyo National Forest list and has now been appropriately added to the Sierra National Forest list. SFL et al. comments on draft SCC list (2-1-16) 1 I. General Concerns about SCC Determinations A. Use of Best Available Science Information Not Documented It is very concerning that there has been little to no attempt to connect the rationale for the proposed SCC designations to the sources. Although the spreadsheets provide lists of sources used, those sources are extremely scant and therefore insufficient to meet the BASI standard. -

Subject Index

Subject Index 1,2 dibromo 3 chloropropane 1658 adsorbed organic material: Agricultural ecosystems 37 17 beta estradiol 545 concentrated bacterial agricultural education 41, 514 2,4 D 177 substrate source 1618 agricultural effluent 613 21st Century 731 adsorbents 8 agricultural fields 897, 1348 3,5,6 trichloro 2 pyridinol 1397 adsorption 9, 439, 695, 1116, 1563, Agricultural & general applied abandoned land 215 1578 entomology 183, 387, 422, Abandoned mined lands Advanced treatment 1159 477, 506, 754, 761, 949, 1074, reclamation 631 Advanced Wastewater Treatment 1193, 1342, 1473, 1577, 1644, abandoned peatland 659 1159 1659, 1707 abatement cost 1758 adverse effects 834, 961, 1118, agricultural irrigation 487 abiotic factors 1352 1727 agricultural land 25, 43, 46, 52, 94, abiotic injuries 579 aeration 16, 186, 1185, 1266 107, 123, 153, 155, 212, 273, abiotic transformations 480 aeration zone 337 295, 320, 341, 428, 464, 533, aboveground biomass [AGBM] Aerial colonization 1635 538, 929, 976, 990, 1018, 1096, 812 aerial insects 691 1136, 1141, 1156, 1196, 1198, Abrasion 1461 aerial pesticide 366 1241, 1268, 1357, 1386, 1421, abscisic acid 1591 aerial photography 539, 1328 1424, 1457, 1501, 1502, 1538, absorption 671, 1202, 1376 Aerial photography in watershed 1571, 1622, 1718, 1759 Abundance 1101 management---United States agricultural land use 24 Acari 1342 1703 Agricultural lands 266 acaricides 747 aerobic sediments 1468 agricultural landscape 795 Accipiter gentilis 424, 1708 aerodynamic profile 916 Agricultural landscape Accumulation 1159 -

FEIS Citation Retrieval System Keywords

FEIS Citation Retrieval System Keywords 29,958 entries as KEYWORD (PARENT) Descriptive phrase AB (CANADA) Alberta ABEESC (PLANTS) Abelmoschus esculentus, okra ABEGRA (PLANTS) Abelia × grandiflora [chinensis × uniflora], glossy abelia ABERT'S SQUIRREL (MAMMALS) Sciurus alberti ABERT'S TOWHEE (BIRDS) Pipilo aberti ABIABI (BRYOPHYTES) Abietinella abietina, abietinella moss ABIALB (PLANTS) Abies alba, European silver fir ABIAMA (PLANTS) Abies amabilis, Pacific silver fir ABIBAL (PLANTS) Abies balsamea, balsam fir ABIBIF (PLANTS) Abies bifolia, subalpine fir ABIBRA (PLANTS) Abies bracteata, bristlecone fir ABICON (PLANTS) Abies concolor, white fir ABICONC (ABICON) Abies concolor var. concolor, white fir ABICONL (ABICON) Abies concolor var. lowiana, Rocky Mountain white fir ABIDUR (PLANTS) Abies durangensis, Coahuila fir ABIES SPP. (PLANTS) firs ABIETINELLA SPP. (BRYOPHYTES) Abietinella spp., mosses ABIFIR (PLANTS) Abies firma, Japanese fir ABIFRA (PLANTS) Abies fraseri, Fraser fir ABIGRA (PLANTS) Abies grandis, grand fir ABIHOL (PLANTS) Abies holophylla, Manchurian fir ABIHOM (PLANTS) Abies homolepis, Nikko fir ABILAS (PLANTS) Abies lasiocarpa, subalpine fir ABILASA (ABILAS) Abies lasiocarpa var. arizonica, corkbark fir ABILASB (ABILAS) Abies lasiocarpa var. bifolia, subalpine fir ABILASL (ABILAS) Abies lasiocarpa var. lasiocarpa, subalpine fir ABILOW (PLANTS) Abies lowiana, Rocky Mountain white fir ABIMAG (PLANTS) Abies magnifica, California red fir ABIMAGM (ABIMAG) Abies magnifica var. magnifica, California red fir ABIMAGS (ABIMAG) Abies -

Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service

Thursday, August 24, 2006 Part III Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 10 General Provisions; Revised List of Migratory Birds; Proposed Rule VerDate Aug<31>2005 17:46 Aug 23, 2006 Jkt 208001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\24AUP2.SGM 24AUP2 rwilkins on PROD1PC63 with PROPOSAL_2 50194 Federal Register / Vol. 71, No. 164 / Thursday, August 24, 2006 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 712), and the Fish and Wildlife Act of conform with accepted usage; (9) change 1956 (16 U.S.C. 742a–j). The MBTA the scientific names of 64 species to Fish and Wildlife Service implements treaties between the United conform with accepted usage; (10) States and four neighboring countries change the common and scientific 50 CFR Part 10 for the protection of migratory birds, as names of 7 species to conform with RIN 1018–AB72 follows: accepted usage; (11) change the (1) Canada: Convention for the scientific names of 4 species in the General Provisions; Revised List of Protection of Migratory Birds, August alphabetical list to conform with Migratory Birds 16, 1916, United States-Great Britain (on accepted usage and to correct behalf of Canada), 39 Stat. 1702, T.S. inconsistencies between the AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, No. 628; alphabetical and taxonomic lists; (12) Interior. (2) Mexico: Convention for the correct errors in the common (English) ACTION: Proposed rule. Protection of Migratory Birds and Game name of 2 species; (13) correct errors in Mammals, February 7, 1936, United the scientific names of 3 species in the SUMMARY: We, the U.S. -

Management of Western Forests and Grasslands

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. USE OF MONTANE MEADOWS BY BIRDS Fred B. Samson Assistant Leader Missouri Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service 112 Stephens Hall, University of Missouri Columbia, MO 65211 ABSTRACT Montane meadows comprise about 3.2 million ha under the jurisdiction of the U. S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and state and private ownership. Relatively few species of birds breed on montane meadows, but meadows serve as important foraging,areas for avian communities associated with nearby riparian or forest habitats. Recommendations for management of montane meadows include: (1) care should be exercised in grazing or other land-use prescriptions such as fire, considering their apparent accelerative effect on meadow succession; (2) information is needed on the effect of meadow size on the diversity of breeding and foraging birds to fully predict the effect of land use changes; and (3) detailed studies involving marked individuals rather than singing male counts are needed to ensure accurate estimates of densities and essential habitat needs of breeding birds. KEYWORDS: montane meadows, meadow succession, nongpme wildlife management, avian ecology. In successfully occupying higher elevations, birds have accommodated a complex of environmental conditions--extensive solar radiation particularly in the ultraviolet spectrum, reduced air and oxygen pressure, intense night cooling by reradiation of heat, low atmospheric humidity, persistent wind, and, in winter, deep snowpack (Brinck 1974). Thus, high montane avifaunas are generally poor in species; populations often are small, reflecting low primary productivity; and densities vary from locale to locale (Dorst 1974). -

Volume 2, Chapter 16-7: Bird Nests-Passeriformes, Part 2

Glime, J. M. 2017. Bird Nests – Passeriformes, part 2. Chapt. 16-7. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 2. Bryological 16-7-1 Interaction. eBook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 19 July 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology2/>. CHAPTER 16-7 BIRD NESTS – PASSERIFORMES, PART 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Passeriformes (cont.) Grallariidae ................................................................................................................................................ 16-7-2 Regulidae – Kinglets .................................................................................................................................. 16-7-2 Sylviidae – Old-World Warblers and Gnatcatchers ................................................................................... 16-7-3 Turdidae – Thrushes ................................................................................................................................... 16-7-3 Muscicapidae – Old World Flycatchers ..................................................................................................... 16-7-9 Petroicidae – Australian Robins ............................................................................................................... 16-7-10 Sturnidae – Starlings etc .......................................................................................................................... 16-7-10 Motacillidae – Wagtails and Pipits ......................................................................................................... -

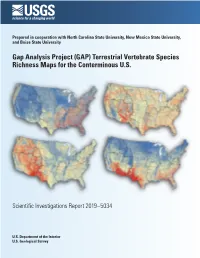

Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S

Prepared in cooperation with North Carolina State University, New Mexico State University, and Boise State University Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S. Scientific Investigations Report 2019–5034 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Mosaic of amphibian, bird, mammal, and reptile species richness maps derived from species’ habitat distribution models of the conterminous United States. Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S. By Kevin J. Gergely, Kenneth G. Boykin, Alexa J. McKerrow, Matthew J. Rubino, Nathan M. Tarr, and Steven G. Williams Prepared in cooperation with North Carolina State University, New Mexico State University, and Boise State University Scientific Investigations Report 2019–5034 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text.