Stanford Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cops Or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 5 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dimitri Epstein, Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epstein: Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute App COPS OR ROBBERS? HOW GEORGIA'S DEFENSE OF HABITATION STATUTE APPLIES TO NONO- KNOCK RAIDS BY POLICE Dimitri Epstein*Epstein * INTRODUCTION Late in the fall of 2006, the city of Atlanta exploded in outrage when Kathryn Johnston, a ninety-two-year old woman, died in a shoot-out with a police narcotics team.team.' 1 The police used a "no"no- knock" search warrant to break into Johnston's home unannounced.22 Unfortunately for everyone involved, Ms. Johnston kept an old revolver for self defense-not a bad strategy in a neighborhood with a thriving drug trade and where another elderly woman was recently raped.33 Probably thinking she was being robbed, Johnston managed to fire once before the police overwhelmed her with a "volley of thirty-nine" shots, five or six of which proved fatal.fata1.44 The raid and its aftermath appalled the nation, especially when a federal investigation exposed the lies and corruption leading to the incident. -

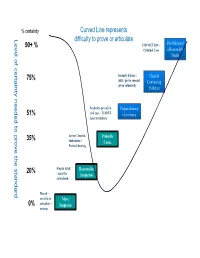

Level of Certainty Needed to Prove the Standard

% certainty Curved Line represents Level of certainty needed to prove the standard needed toprove of certainty Level difficulty to prove or articulate 90+ % CONVICTION – Proof Beyond Criminal Case a Reasonable Doubt 75% Insanity defense / Clear & alibi / prove consent Convincing given voluntarily Evidence Needed to prevail in Preponderance 51% civil case – LIABLE of evidence Asset Forfeiture 35% Arrest / Search / Probable Indictment / Cause Pretrial hearing 20% Stop & Frisk Reasonable – must be Suspicion articulated Hunch – not able to Mere 0% articulate / Suspicion no stop Mere Suspicion – This term is used by the courts to refer to a hunch or intuition. We all experience this in everyday life but it is NOT enough “legally” to act on. It does not mean than an officer cannot observe the activity or person further without making contact. Mere suspicion cannot be articulated using any reasonably accepted facts or experiences. An officer may always make a consensual contact with a citizen without any justification. The officer will however have not justification to stop or hold a person under this situation. One might say something like, “There is just something about him that I don’t trust”. “I can’t quit put my finger on what it is about her.” “He looks out of place.” Reasonable Suspicion – Stop, Frisk for Weapons, *(New) Search of vehicle incident to arrest under Arizona V. Gant. The landmark case for reasonable suspicion is Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) This level of proof is the justification police officers use to stop a person under suspicious circumstances (e.g. a person peaking in a car window at 2:00am). -

Ronald Cornish V. State of Maryland, No. 12, September Term, 2018

Ronald Cornish v. State of Maryland, No. 12, September Term, 2018. Opinion by Greene, J. CRIMINAL PROCEDURE – MARYLAND RULE 4-331 – NEWLY DISCOVERED EVIDENCE – PRIMA FACIE The Court of Appeals held that the facts alleged in Petitioner’s Motion for New Trial on the grounds of Newly Discovered Evidence established a prima facie basis for granting a new trial. CRIMINAL PROCEDURE – MARYLAND RULE 4-331 – NEWLY DISCOVERED EVIDENCE – RIGHT TO A HEARING The Court of Appeals held that the Circuit Court erred when it denied Petitioner a hearing on his Rule 4-331 Motion for New Trial based on Newly Discovered Evidence. Circuit Court for Baltimore City IN THE COURT OF APPEALS Case No. 115363026 Argued: September 12, 2018 OF MARYLAND No. 12 September Term, 2018 ______________________________________ RONALD CORNISH v. STATE OF MARYLAND Barbera, C.J. Greene, Adkins, McDonald, Watts, Hotten, Getty, JJ. ______________________________________ Opinion by Greene, J. ______________________________________ Filed: October 30, 2018 In this case, we consider under what circumstances a defendant has the right to a hearing upon filing a Maryland Rule 4-331(c) Motion for New Trial based on newly discovered evidence. More specifically, we must decide whether the trial judge was legally correct in denying Petitioner Ronald Cornish (“Mr. Cornish”) a hearing under the Rule. Petitioner was charged and convicted of first degree murder, use of a firearm in the commission of a crime of violence, and other related offenses. Thereafter, Mr. Cornish was sentenced to life imprisonment plus twenty years. Approximately two weeks after his sentencing, Mr. Cornish filed a Motion for a New Trial under Md. -

BAIL JUMPING in the THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action Or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on Or After Sept

BAIL JUMPING IN THE THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on or after Sept. 8, 1983) The (specify) count is Bail Jumping in the Third Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of Bail Jumping in the Third Degree when by court order he or she has been released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty, either upon bail or upon his or her own recognizance, upon condition that he or she will subsequently appear personally in connection with a criminal action or proceeding1, and when he or she does not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. In order for you to find the defendant guilty of this crime, the People are required to prove, from all of the evidence in the case, beyond a reasonable doubt, both of the following two elements: 1. That the defendant, (defendant’s name) was, by court order, released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty upon bail [or upon his/her own recognizance] upon condition that he/she would subsequently appear personally on (date) in (county) in connection with a criminal action or proceeding; and 2. That the defendant did not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. Note: If the affirmative defense does not apply, conclude as follows: If you find the People have proven beyond a reasonable doubt both of those elements, you must find the defendant guilty 1 If in issue, define criminal action or criminal proceeding in accordance with CPL 1.20(16) and (18). -

Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial

William & Mary Law Review Volume 37 (1995-1996) Issue 1 Article 10 October 1995 Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial Alan L. Adlestein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Alan L. Adlestein, Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial, 37 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 199 (1995), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol37/iss1/10 Copyright c 1995 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr CONFLICT OF THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS WITH LESSER OFFENSES AT TRIAL ALAN L. ADLESTEIN I. INTRODUCTION ............................... 200 II. THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS AND LESSER OFFENSES-DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONFLICT ........ 206 A. Prelude: The Problem of JurisdictionalLabels ..... 206 B. The JurisdictionalLabel and the CriminalStatute of Limitations ................ 207 C. The JurisdictionalLabel and the Lesser Offense .... 209 D. Challenges to the Jurisdictional Label-In re Winship, Keeble v. United States, and United States v. Wild ..................... 211 E. Lesser Offenses and the Supreme Court's Capital Cases- Beck v. Alabama, Spaziano v. Florida, and Schad v. Arizona ........................... 217 1. Beck v. Alabama-LegislativePreclusion of Lesser Offenses ................................ 217 2. Spaziano v. Florida-Does the Due Process Clause Require Waivability? ....................... 222 3. Schad v. Arizona-The Single Non-Capital Option ....................... 228 F. The Conflict Illustrated in the Federal Circuits and the States ....................... 230 1. The Conflict in the Federal Circuits ........... 232 2. The Conflict in the States .................. 234 III. -

Reasonable Cause Exists When the Public Servant Has

ESCAPE IN THE SECOND DEGREE Penal Law § 205.10(2) (Escape from Custody by Defendant Arrested for, Charged with, or Convicted of Felony) (Committed on or after September 8, 1983) The (specify) count is Escape in the Second Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of escape in the second degree when, having been arrested for [or charged with] [or convicted of] a class C [or class D] [or class E] felony, he or she escapes from custody. The following terms used in that definition have a special meaning: CUSTODY means restraint by a public servant pursuant to an authorized arrest or an order of a court.1 "Public Servant" means any public officer or employee of the state or of any political subdivision thereof or of any governmental instrumentality within the state, [or any person exercising the functions of any such public officer or employee].2 [Add where appropriate: An arrest is authorized when the public servant making the arrest has reasonable cause to believe that the person being arrested has committed a crime. 3 Reasonable cause does not require proof that the crime was in fact committed. Reasonable cause exists when the public servant has 1 Penal Law §205.00(2). 2 Penal Law §10.00(15). 3 This portion of the charge assumes an arrest for a crime only as authorized by the provisions of CPL 140.10(1)(b). If the arrest was authorized pursuant to some other subdivision of CPL 140.10 or other law, substitute the applicable provision of law. knowledge of facts and circumstances sufficient to support a reasonable belief that a crime has been or is being committed.4 ] ESCAPE means to get away, break away, get free or get clear, with the conscious purpose to evade custody.5 (Specify the felony for which the defendant was arrested, charged or convicted) is a class C [or class D] [or class E] felony. -

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness" in Our Constitutional Jurisprudence: an Exercise in Legal History

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 20 (2011-2012) Issue 2 Article 4 December 2011 Restoring "Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness" in Our Constitutional Jurisprudence: An Exercise in Legal History Patrick J. Charles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Legal History Commons Repository Citation Patrick J. Charles, Restoring "Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness" in Our Constitutional Jurisprudence: An Exercise in Legal History, 20 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 457 (2011), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol20/iss2/4 Copyright c 2011 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj RESTORING “LIFE, LIBERTY, AND THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS” IN OUR CONSTITUTIONAL JURISPRUDENCE: AN EXERCISE IN LEGAL HISTORY Patrick J. Charles* INTRODUCTION .................................................458 I. PLACING THE DECLARATION IN LEGAL AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT .....461 II. A BRIEF HISTORIOGRAPHY OF “LIFE, LIBERTY, AND THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS” AS A MATTER OF LEGAL THOUGHT, WITH A FOCUS ON “HAPPINESS” ...............................................470 III. PLACING THE INTERRELATIONSHIP OF “LIFE, LIBERTY, AND THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS” IN THE CONTEXT OF AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONALISM ...477 A. Restoring the True Meaning of the Preservation of “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness” in Constitutional Thought .............481 B. “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness” and the Embodiment of the Representative Government ..............................490 C. Eighteenth-Century Legal Thought and the Constitutional Theory Behind Preservation of “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness” ......502 IV. APPLYING THE PRESERVATION OF “LIFE, LIBERTY, AND THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS” TO MODERN CONSTITUTIONALISM .....................517 CONCLUSION—OUR HAPPY CONSTITUTION ...........................523 * Patrick J. -

Burden of Proof and 4Th Amendment

Burden of Proof and 4 th Amendment Burden of Proof Standards • Reasonable suspicion • Probable cause • Reasonable doubt Burden of proof • In the United States we enjoy a ‘presumption of innocence’. What does this mean? • This means, essentially, that you are innocent until proven guilty. But how do we prove guilt? • Law enforcement officers must have some basis for stopping or detaining an individual. • In order for an officer to stop and detain someone they must meet a standard of proof Reasonable Suspicion • Lowest standard • A belief or suspicion that • Officers cannot deprive a citizen of liberty unless the officer can point to specific facts and circumstances and inferences therefrom that would amount to a reasonable suspicion Probable Cause • More likely than not or probably true. • Probable cause- a reasonable amount of suspicion, supported by circumstances sufficiently strong to justify a prudent and cautious person’s belief that certain facts are probably true. • In other terms this could be understood as more likely than not of 51% likely. • This is the standard required to arrest someone and obtain a warrant. Reasonable Doubt • Beyond a reasonable doubt- This means that the notion being presented by the prosecution must be proven to the extent that there could be no "reasonable doubt" in the mind of a “reasonable person” that the defendant is guilty. There can still be a doubt, but only to the extent that it would not affect a reasonable person's belief regarding whether or not the defendant is guilty. 4th Amendment • Search -

The Reasonable Investor of Federal Securities Law

This article was originally published as: Amanda M. Rose The Reasonable Investor of Federal Securities Law 43 The Journal of Corporation Law 77 (2017) +(,121/,1( Citation: Amanda M. Rose, The Reasonable Investor of Federal Securities Law: Insights from Tort Law's Reasonable Person & Suggested Reforms, 43 J. Corp. L. 77 (2017) Provided by: Vanderbilt University Law School Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Tue Apr 3 17:02:15 2018 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device The "Reasonable Investor" of Federal Securities Law: Insights from Tort Law's "Reasonable Person" & Suggested Reforms Amanda M. Rose* Federalsecurities law defines the materiality ofcorporatedisclosures by reference to the views of a hypothetical "reasonableinvestor. " For decades the reasonable investor standardhas been aflashpointfor debate-with critics complaining of the uncertainty it generates and defenders warning of the under-inclusiveness of bright-line alternatives. This Article attempts to shed fresh light on the issue by considering how the reasonable investor differs from its common law antecedent, the reasonableperson of tort law. The differences identified suggest that the reasonableinvestor standardis more costly than tort, law's reasonableperson standard-theuncertainty it generates is both greater and more pernicious. But the analysis also reveals promising ways to mitigate these costs while retainingthe benefits of theflexible standard 1. -

Defamation Law - the Private Plaintiff Must Establish a New Element to Make a Prima Facie Showing: Philadelphia Newspapers, Inc

Volume 17 Issue 2 Summer 1987 Summer 1987 Defamation Law - The Private Plaintiff Must Establish a New Element to Make a Prima Facie Showing: Philadelphia Newspapers, Inc. v. Hepps Debra A. Hill Recommended Citation Debra A. Hill, Defamation Law - The Private Plaintiff Must Establish a New Element to Make a Prima Facie Showing: Philadelphia Newspapers, Inc. v. Hepps, 17 N.M. L. Rev. 363 (1987). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmlr/vol17/iss2/8 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by The University of New Mexico School of Law. For more information, please visit the New Mexico Law Review website: www.lawschool.unm.edu/nmlr DEFAMATION LAW-The Private Figure Plaintiff Must Establish a New Element to Make a Prima Facie Showing: Philadelphia Newspapers, Inc. v. Hepps I. INTRODUCTION The U.S. Supreme Court decision in Philadelphia Newspapers, Inc. v. Hepps' imposes a new element of proof on private figure plaintiffs2 in media defamation actions.' In Hepps, the Supreme Court held that where a newspaper publishes speech about matters of public interest, the plaintiff now bears the burden of showing that the defamatory statements4 are false.5 This decision abrogates the common law rule that the defendant bears the burden of proving the truth of the defamatory statements.' This Note first discusses the historical background of distinctions enun- ciated by the Court in making decisions in defamation cases: the status of the plaintiff, the contents of the defamatory speech, and the status of the defendant. The Note then reviews the U.S. -

Guide to Ny Evidence Article 3 Presumptions & Prima Facie Evidence

GUIDE TO NY EVIDENCE ARTICLE 3 PRESUMPTIONS & PRIMA FACIE EVIDENCE Table of Contents Presumptions 3.01 Presumptions in Civil Proceedings 3.03 Presumptions in Criminal Proceedings Accorded People 3.05 Presumptions in Criminal Proceedings Accorded Defendant Prima Facie Evidence 3.07 Certificates of Judgments of Conviction & Fingerprints (CPL 60.60) 3.10 Inspection Certificate of US Dept of Agriculture (CPLR 4529) 3.12 Ancient Filed Maps, Surveys & Real Property Records (CPLR 4522) 3.14 Conveyance of Real Property Without the State (CPLR 4524) 3.16 Death or Other Status of a Missing Person (CPLR 4527) 3.18 Marriage Certificate (CPLR 4526; DRL 14-A) 3.20 Affidavit of Service or Posting Notice by Person Unavailable at Trial (CPLR 4531) 3.22 Standard of Measurement Used by Surveyor (CPLR 4534) 3.24 Search by Title Insurance or Abstract Company (CPLR 4523) 3.26 Copies of Statements Under UCC Article 9 (CPLR 4525) 3.28 Weather Conditions (CPLR 4528) 3.01. Presumptions in Civil Proceedings (1) This rule applies in civil proceedings to a “presumption,” which as provided in subdivisions two and three is rebuttable; it does not apply to a “conclusive” presumption, that is, a “presumption” not subject to rebuttal, or to an “inference” which permits, but does not require, the trier of fact to draw a conclusion from a proven fact. (2) A presumption is created by statute or decisional law, and requires that if one fact (the “basic fact”) is established, the trier of fact must find that another fact (the “presumed fact”) is thereby established unless rebutted as provided in subdivision three. -

Criminal Law – Felony Murder – Limitation and Review of Convictions for 3 Children

SENATE BILL 395 E1, E2 1lr0736 HB 1338/20 – JUD CF HB 385 By: Senator Carter Introduced and read first time: January 15, 2021 Assigned to: Judicial Proceedings A BILL ENTITLED 1 AN ACT concerning 2 Criminal Law – Felony Murder – Limitation and Review of Convictions for 3 Children 4 FOR the purpose of altering provisions of law relating to murder in the first degree; 5 providing that a person who was a child at the time of the offense may not be found 6 to have committed murder in the first degree under certain provisions of law; 7 authorizing certain persons to file a motion for review of conviction under certain 8 circumstances; requiring a court to hold a certain hearing on the filing of a motion 9 for review of conviction under certain circumstances; requiring the court to take 10 certain actions under certain circumstances; requiring the court to notify the State’s 11 Attorney of the filing of a certain motion for review of conviction; and generally 12 relating to children and felony first–degree murder. 13 BY repealing and reenacting, with amendments, 14 Article – Criminal Law 15 Section 2–201 16 Annotated Code of Maryland 17 (2012 Replacement Volume and 2020 Supplement) 18 BY repealing and reenacting, without amendments, 19 Article – Criminal Law 20 Section 2–204 21 Annotated Code of Maryland 22 (2012 Replacement Volume and 2020 Supplement) 23 SECTION 1. BE IT ENACTED BY THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF MARYLAND, 24 That the Laws of Maryland read as follows: 25 Article – Criminal Law 26 2–201.