Notes to Proofer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Wars & Global Disorder

on the horizon: Dædalus Ending Civil Wars: Constraints & Possibilities edited by Karl Eikenberry & Stephen D. Krasner Francis Fukuyama, Tanisha M. Fazal, Stathis N. Kalyvas, Steven Heydemann, Chuck Call & Susanna P. Campbell, Sumit Ganguly, Clare Lockhart, Thomas Risse & Eric Stollenwerk, Tanja A. Börzel & Sonja Grimm, Seyoum Mesfi n & Abdeta Beyene, Lyse Doucet, Nancy Lindborg & Joseph Hewitt, Richard Gowan & Stephen John Stedman, and Jean-Marie Guéhenno & Global Disorder: Threats Opportunities 2017 Civil Wars Fall Dædalus Native Americans & Academia Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences edited by Ned Blackhawk, K. Tsianina Lomawaima, Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, Philip J. Deloria, Fall 2017 Loren Ghiglione, Douglas Medin, and Mark Trahant Anti-Corruption: Best Practices edited by Robert I. Rotberg Civil Wars & Global Disorder: Threats & Opportunities Karl Eikenberry & Stephen D. Krasner, guest editors with James D. Fearon Bruce D. Jones & Stephen John Stedman Stewart Patrick · Martha Crenshaw Paul H. Wise & Michele Barry Representing the intellectual community in its breadth Sarah Kenyon Lischer · Vanda Felbab-Brown and diversity, Dædalus explores the frontiers of Hendrik Spruyt · Stephen Biddle · William Reno knowledge and issues of public importance. Aila M. Matanock & Miguel García-Sánchez Barry R. Posen U.S. $15; www.amacad.org; @americanacad Civil War & the Current International System James D. Fearon Abstract: This essay sketches an explanation for the global spread of civil war up to the early 1990s and the partial -

The 'New Middle East,' Revised Edition

9/29/2014 Diplomatist BILATERAL NEWS: India and Brazil sign 3 agreements during Prime Minister's visit to Brazil CONTENTS PRINT VERSION SPECIAL REPORTS SUPPLEMENTS OUR PATRONS MEDIA SCRAPBOOK Home / September 2014 The ‘New Middle East,’ Revised Edition GLOBAL CENTRE STAGE In July 2014, President Obama sent the White House’s Coordinator for the Middle East, Philip Gordon, to address the ‘Israel Conference on Peace’ in Tel-Aviv. ‘How’ Gordon asked ‘will [Israel] have peace if it is unwilling to delineate a border, end the occupation and allow for Palestinian sovereignty, security, and dignity?’ This is a good question, but Dr Emmanuel Navon asks how Israel will achieve peace if it is willing to delineate a border, end the occupation and allow for Palestinian sovereignty, security, and dignity, especially when experience, logic and deduction suggest that the West Bank would turn into a larger and more lethal version of the Gaza Strip after the Israeli withdrawal During the last war between Israel and Hamas (which officially ended with a ceasefire on August 27, 2014), US Secretary of State John Kerry inadvertently created a common ground among rivals: Israel, the Palestinian Authority, Egypt and Jordan all agreed in July 2014 that Kerry had ruined the chances of a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas. Collaborating with Turkey DEFINITION and Qatar to reach a ceasefire was tantamount to calling the neighbourhood’s pyromaniac instead of the fire department to extinguish the fire. Qatar bankrolls Hamas and Turkey advocates on its behalf. While in Paris in July, Kerry was all smiles Diplomat + with Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu whose boss, Recep Erdogan, recently accused Israel of genocide and compared Netanyahu to Hitler. -

O'hanlon Gordon Indyk

Getting Serious About Iraq 1 Getting Serious About Iraq ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Philip H. Gordon, Martin Indyk and Michael E. O’Hanlon In his 29 January 2002 State of the Union address, US President George W. Bush put the world on notice that the United States would ‘not stand aside as the world’s most dangerous regimes develop the world’s most dangerous weapons’.1 Such statements, repeated since then in various forms by the president and some of his top advisers, have rightly been interpreted as a sign of the administration’s determination to overthrow Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein.2 Since the January declaration, however, attempts by the administration to put together a precise plan for Saddam’s overthrow have revealed what experience from previous administrations should have made obvious from the outset: overthrowing Saddam is easier said than done. Bush’s desire to get rid of the Iraqi dictator has so far been frustrated by the inherent difficulties of overthrowing an entrenched regime as well as a series of practical hurdles that conviction alone cannot overcome. The latter include the difficulties of organising the Iraqi opposition, resistance from Arab and European allies, joint chiefs’ concerns about the problems of over-stretched armed forces and intelligence assets and the complications caused by an upsurge in Israeli– Palestinian violence. Certainly, the United States has good reasons to want to get rid of Saddam Hussein. Saddam is a menace who has ordered the invasion of several of his neighbours, killed thousands of Kurds and Iranians with poison gas, turned his own country into a brutal police state and demonstrated an insatiable appetite for weapons of mass destruction. -

HD in 2020: Peacemaking in Perspective → Page 10 About HD → Page 6 HD Governance: the Board → Page 30

June 2021 EN About HD in 2020: HD governance: HD → page 6 Peacemaking in perspective → page 10 The Board → page 30 Annual Report 2020 mediation for peace www.hdcentre.org Trusted. Neutral. Independent. Connected. Effective. The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) mediates between governments, non-state armed groups and opposition parties to reduce conflict, limit the human suffering caused by war and develop opportunities for peaceful settlements. As a non-profit based in Switzerland, HD helps to build the path to stability and development for people, communities and countries through more than 50 peacemaking projects around the world. → Table of contents HD in 2020: Peacemaking in perspective → page 10 COVID in conflict zones → page 12 Social media and cyberspace → page 12 Supporting peace and inclusion → page 14 Middle East and North Africa → page 18 Francophone Africa → page 20 The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) is a private diplomacy organisation founded on the principles of humanity, Anglophone and Lusophone Africa → page 22 impartiality, neutrality and independence. Its mission is to help prevent, mitigate and resolve armed conflict through dialogue and mediation. Eurasia → page 24 Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) Asia → page 26 114 rue de Lausanne, 1202 – Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 (0)22 908 11 30 Email: [email protected] Latin America → page 28 Website: www.hdcentre.org Follow HD on Twitter and Linkedin: https://twitter.com/hdcentre https://www.linkedin.com/company/centreforhumanitariandialogue Design and layout: Hafenkrone © 2021 – Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue About HD governance: Investing Reproduction of all or part of this publication may be authorised only with written consent or acknowledgement of the source. -

America's Anxious Allies: Trip Report from Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel by Meghan O'sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, James Jeffrey

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2696 America's Anxious Allies: Trip Report from Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel by Meghan O'Sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, James Jeffrey Sep 28, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Meghan O'Sullivan Meghan O'Sullivan is the Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor of the Practice of International Affairs at Harvard University's Kennedy School. Philip Gordon Philip Gordon is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a former White House coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Gulf region. Dennis Ross Dennis Ross, a former special assistant to President Barack Obama, is the counselor and William Davidson Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute. James Jeffrey Ambassador is a former U.S. special representative for Syria engagement and former U.S. ambassador to Turkey and Iraq; from 2013-2018 he was the Philip Solondz Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute. He currently chairs the Wilson Center’s Middle East Program. Brief Analysis A bipartisan team of distinguished former officials share their insights from a recent tour of key regional capitals. On September 26, The Washington Institute held a Policy Forum with Meghan O'Sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, and James Jeffrey, who recently returned from a bipartisan tour of Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel. O'Sullivan is the Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor at Harvard's Kennedy School and former special assistant to the president for Iraq and Afghanistan. Gordon is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and former White House coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Gulf region. -

Seeking Stability at Sustainable Cost: Principles for a New U.S

Seeking Stability at Sustainable Cost: Principles for a New U.S. Strategy in the Middle East Report of the Task Force on Managing Disorder in the Middle East April 2017 Aaron Lobel Task Force Co-Chairs Founder and President, America Abroad Media Ambassador Eric Edelman Former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Mary Beth Long Former Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Jake Sullivan Affairs Former Director of Policy Planning, U.S. State Department Former National Security Advisor to the Vice President Alan Makovsky Former Senior Professional Staff Member, House Foreign Affairs Committee Task Force Members Ray Takeyh Ambassador Morton Abramowitz Former Senior Advisor on Iran, U.S. State Department Former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey General Charles Wald (ret., USAF) Henri Barkey Former Deputy Commander, U.S. European Command Director, Middle East Program, Woodrow Wilson International Center Former Commander, U.S. Central Command Air Forces Hal Brands Amberin Zaman Henry A. Kissinger Distinguished Professor of Global Affairs at the Columnist, Al-Monitor; Woodrow Wilson Center Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies Svante Cornell Staff Director, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program Blaise Misztal Director of National Security Ambassador Ryan Crocker Former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon Nicholas Danforth Senior Policy Analyst Ambassador Robert Ford Former Ambassador to Syria Jessica Michek Policy Analyst John Hannah Former Assistant for National Security Affairs to the Vice President Ambassador James Jeffrey Former Ambassador to Turkey and Iraq DISCLAIMER The findings and recommendations expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s founders or its board of directors. -

The US Perspective on NATO Under Trump: Lessons of the Past and Prospects for the Future

The US perspective on NATO under Trump: lessons of the past and prospects for the future JOYCE P. KAUFMAN Setting the stage With a new and unpredictable administration taking the reins of power in Wash- ington, the United States’ future relationship with its European allies is unclear. The European allies are understandably concerned about what the change in the presidency will mean for the US relationship with NATO and the security guar- antees that have been in place for almost 70 years. These concerns are not without foundation, given some of the statements Trump made about NATO during the presidential campaign—and his description of NATO on 15 January 2017, just days before his inauguration, as ‘obsolete’. That comment, made in a joint interview with The Times of London and the German newspaper Bild, further exacerbated tensions between the United States and its closest European allies, although Trump did claim that the alliance is ‘very important to me’.1 The claim that it is obsolete rested on Trump’s incorrect assumption that the alliance has not been engaged in the fight against terrorism, a position belied by NATO’s support of the US conflict in Afghanistan. Among the most striking observations about Trump’s statements on NATO is that they are contradicted by comments made in confirmation hear- ings before the Senate by General James N. Mattis (retired), recently confirmed as Secretary of Defense, who described the alliance as ‘essential for Americans’ secu- rity’, and by Rex Tillerson, now the Secretary of State.2 It is important to note that the concerns about the future relationships between the United States and its NATO allies are not confined to European governments and policy analysts. -

Lessons-Encountered.Pdf

conflict, and unity of effort and command. essons Encountered: Learning from They stand alongside the lessons of other wars the Long War began as two questions and remind future senior officers that those from General Martin E. Dempsey, 18th who fail to learn from past mistakes are bound Excerpts from LChairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: What to repeat them. were the costs and benefits of the campaigns LESSONS ENCOUNTERED in Iraq and Afghanistan, and what were the LESSONS strategic lessons of these campaigns? The R Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University was tasked to answer these questions. The editors com- The Institute for National Strategic Studies posed a volume that assesses the war and (INSS) conducts research in support of the Henry Kissinger has reminded us that “the study of history offers no manual the Long Learning War from LESSONS ENCOUNTERED ENCOUNTERED analyzes the costs, using the Institute’s con- academic and leader development programs of instruction that can be applied automatically; history teaches by analogy, siderable in-house talent and the dedication at the National Defense University (NDU) in shedding light on the likely consequences of comparable situations.” At the of the NDU Press team. The audience for Washington, DC. It provides strategic sup- strategic level, there are no cookie-cutter lessons that can be pressed onto ev- Learning from the Long War this volume is senior officers, their staffs, and port to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman ery batch of future situational dough. The only safe posture is to know many the students in joint professional military of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and unified com- historical cases and to be constantly reexamining the strategic context, ques- education courses—the future leaders of the batant commands. -

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs March 1, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30588 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Summary During 2009, the Obama Administration addressed a deteriorating security environment in Afghanistan. Despite an increase in U.S. forces there during 2006-2008, insurgents were expanding their area and intensity of operations, resulting in higher levels of overall violence. There was substantial Afghan and international disillusionment with corruption in the government of Afghan President Hamid Karzai, and militants enjoyed a safe haven in parts of Pakistan. Building on assessments completed in the latter days of the Bush Administration, the Obama Administration conducted two “strategy reviews,” the results of which were announced on March 27, 2009, and on December 1, 2009, respectively. Each review included a decision to add combat troops, with the intent of creating the conditions to expand Afghan governance and economic development, rather than on hunting and defeating insurgents in successive operations. The new strategy has been propounded by Gen. Stanley McChrystal, who was appointed top U.S. and NATO commander in Afghanistan in May 2009. In his August 30, 2009, initial assessment of the situation, Gen. McChrystal recommended a fully resourced, comprehensive counter-insurgency strategy that could require about 40,000 additional forces (beyond 21,000 additional U.S. forces authorized in February 2009). On December 1, 2009, following the second high level policy review, President Obama announced the following: • The provision of 30,000 additional U.S. -

Consumed by Corruption More Stories

THE AFGHANISTAN PAPERS Part 4: Consumed by corruption More stories THE AFGHANISTAN PAPERS A secret history of the war CONSUMED BY CORRUPTION The U.S. flooded the country with money — then turned a blind eye to the graft it fueled By Craig Whitlock Dec. 9, 2019 bout halfway into the 18-year war, Afghans stopped hiding how corrupt their country had become. THE AFGHANISTAN PAPERS Part 4: Consumed by corruption More stories A Dark money sloshed all around. Afghanistan’s largest bank liquefied into a cesspool of fraud. Travelers lugged suitcases loaded with $1 million, or THE AFGHANISTAN PAPERS Part 4: Consumed by corruptionmore, on flights leaving Kabul. More stories KABUL, 20122006 (Yuri(Gary Kozyrev/Noor) Knight/VII/Redux) Mansions known as “poppy palaces” rose from the rubble to house opium kingpins. THE AFGHANISTAN PAPERS Part 4: Consumed by corruptionPresident Hamid Karzai won reelection after cronies stuffed thousands of More stories ballot boxes. He later admitted the CIA had delivered bags of cash to his office for years, calling it “nothing unusual.” In public, as President Barack Obama escalated the war and Congress approved billions of additional dollars in support, the commander in chief and lawmakers promised to crack down on corruption and hold crooked Afghans accountable. In reality, U.S. officials backed off, looked away and let the thievery become more entrenched than ever, according to a trove of confidential government interviews obtained by The Washington Post. In the interviews, key figures in the war said Washington tolerated the worst offenders — warlords, drug traffickers, defense contractors — because they were allies of the United States. -

The U.S. Surge and Afghan Local Governance

UNITeD StateS INSTITUTe of Peace www.usip.org SPeCIAL RePoRT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Frances Z. Brown This report focuses on both the U.S. military’s localized governance, reconstruction, and development projects and U.S. civilian stabilization programming in Afghanistan from 2009 through 2012. Based on interviews with nearly sixty Afghan and international respondents in Kabul, Kandahar, Nangarhar, The U.S. Surge and and Washington, this report finds that the surge has not met its transformative objectives due to three U.S. assumptions that proved unrealistic. It also examines lessons from the U.S. surge’s impacts on local governance that can be applied toward Afghan Local Governance Afghanistan’s upcoming transition. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Lessons for Transition Frances Z. Brown is a 2011–12 International Affairs Fellow with the Council on Foreign Relations and an Afghanistan Fellow at the United States Institute of Peace. She has worked in and on Summary Afghanistan since 2004, and her previous jobs included roles with the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit and the • The U.S. military and civilian surge into Afghanistan starting in late 2009 aimed to stabilize United States Agency for International Development. She holds the country through interconnected security, governance, and development initiatives. an MA from Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International • Despite policymakers’ claims that their goals for Afghan governance were “modest,” the Studies and a BA from Yale University. The views in this report surge’s stated objectives amounted to a transformation of the subnational governance are solely her own and do not reflect the views of the U.S. -

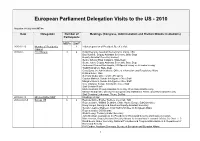

The Information Below Is Based on the Information Supplied to EPLO and Stored in Its Archives and May Differ from the Fina

European Parliament Delegation Visits to the US - 2010 Situation: 01 July 2010 MT/mt Date Delegation Number of Meetings (Congress, Administration and Bretton-Woods Institutions) Participants MEPs Staff* 2010-02-16 Member of President's 1 Initial preparation of President Buzek´s Visit Cabinet 2010-02- ECR Bureau 9 4 David Heyman, Assistant Secretary for Policy, TSA Dan Russell, Deputy Assistant Secretary ,State Dept Deputy Assistant Secretary Limbert, Senior Advisor Elisa Catalano, State Dept Stuart Jones, Deputy Assistant Secretary, State Dept Ambassor Richard Morningstar, US Special Envoy on Eurasian Energy Todd Holmstrom, State Dept Cass Sunstein, Administrator, Office of Information and Regulatory Affiars Kristina Kvien, NSC Sumona Guha, Office of Vice-President Gordon Matlock, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Margaret Evans, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Clee Johnson, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Staff Senator Risch Mark Koumans, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Dept Homeland Security Michael Scardeville, Director for European and Multilateral Affairs, Dept Homeland Security Staff Senators Lieberman, Thune, DeMint 2010-02-18 Mrs Lochbihler MEP 1 Meetings on Iran 2010-03-03-5 Bureau US 6 2 Representative Shelley Berkley, Co-Chair, TLD Representative William Delahunt, Chair, House Europe SubCommittee Doug Hengel, Energy and Sanctions Deputy Assistant Secretary Senator Jeanne Shaheen, Chair Subcommittee on European Affairs Representative Cliff Stearns Stuart Levey, Treasury Under Secretary John Brennan, Assistant to the President for