Chapter Five Fission Before Fusion and the Rarity of Atoms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

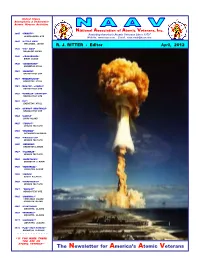

2012 04 Newsletter

United States Atmospheric & Underwater Atomic Weapon Activities National Association of Atomic Veterans, Inc. 1945 “TRINITY“ “Assisting America’s Atomic Veterans Since 1979” ALAMOGORDO, N. M. Website: www.naav.com E-mail: [email protected] 1945 “LITTLE BOY“ HIROSHIMA, JAPAN R. J. RITTER - Editor April, 2012 1945 “FAT MAN“ NAGASAKI, JAPAN 1946 “CROSSROADS“ BIKINI ISLAND 1948 “SANDSTONE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “RANGER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1951 “GREENHOUSE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “BUSTER – JANGLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “TUMBLER - SNAPPER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “IVY“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1953 “UPSHOT - KNOTHOLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1954 “CASTLE“ BIKINI ISLAND 1955 “TEAPOT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1955 “WIGWAM“ OFFSHORE SAN DIEGO 1955 “PROJECT 56“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1956 “REDWING“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1957 “PLUMBOB“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1958 “HARDTACK-I“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1958 “NEWSREEL“ JOHNSTON ISLAND 1958 “ARGUS“ SOUTH ATLANTIC 1958 “HARDTACK-II“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1961 “NOUGAT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1962 “DOMINIC-I“ CHRISTMAS ISLAND JOHNSTON ISLAND 1965 “FLINTLOCK“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1969 “MANDREL“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1971 “GROMMET“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1974 “POST TEST EVENTS“ ENEWETAK CLEANUP ------------ “ IF YOU WERE THERE, YOU ARE AN ATOMIC VETERAN “ The Newsletter for America’s Atomic Veterans COMMANDER’S COMMENTS knowing the seriousness of the situation, did not register any Outreach Update: First, let me extend our discomfort, or dissatisfaction on her part. As a matter of fact, it thanks to the membership and friends of NAAV was kind of nice to have some of those callers express their for supporting our “outreach” efforts over the thanks for her kind attention and assistance. We will continue past several years. It is that firm dedication to to insure that all inquires, along these lines, are fully and our Mission-Statement that has driven our adequately addressed. -

Nuclear Technology

Nuclear Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. GREENWOOD PRESS NUCLEAR TECHNOLOGY Sourcebooks in Modern Technology Space Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. Sourcebooks in Modern Technology Nuclear Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Angelo, Joseph A. Nuclear technology / Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. p. cm.—(Sourcebooks in modern technology) Includes index. ISBN 1–57356–336–6 (alk. paper) 1. Nuclear engineering. I. Title. II. Series. TK9145.A55 2004 621.48—dc22 2004011238 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2004 by Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2004011238 ISBN: 1–57356–336–6 First published in 2004 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 To my wife, Joan—a wonderful companion and soul mate Contents Preface ix Chapter 1. History of Nuclear Technology and Science 1 Chapter 2. Chronology of Nuclear Technology 65 Chapter 3. Profiles of Nuclear Technology Pioneers, Visionaries, and Advocates 95 Chapter 4. How Nuclear Technology Works 155 Chapter 5. Impact 315 Chapter 6. Issues 375 Chapter 7. The Future of Nuclear Technology 443 Chapter 8. Glossary of Terms Used in Nuclear Technology 485 Chapter 9. Associations 539 Chapter 10. -

Kimmo Mäkilä Tuhoa, Tehoa Ja Tuhlausta

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 84 Kimmo Mäkilä Tuhoa, tehoa ja tuhlausta Helsingin Sanomien ja New York Timesin ydinaseuutisoinnin tarkastelua diskurssianalyyttisesta näkökulmasta 1945–1998 Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Paulaharjun salissa joulukuun 15. päivänä 2007 kello 12. JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Tuhoa, tehoa ja tuhlausta Helsingin Sanomien ja New York Timesin ydinaseuutisoinnin tarkastelua diskurssianalyyttisesta näkökulmasta 1945–1998 JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 84 Kimmo Mäkilä Tuhoa, tehoa ja tuhlausta Helsingin Sanomien ja New York Timesin ydinaseuutisoinnin tarkastelua diskurssianalyyttisesta näkökulmasta 1945–1998 JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Raimo Salokangas Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä Pekka Olsbo, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä Cover Picture by Janne Ikonen ISBN 978-951-39-2988-6 ISSN 1459-4323 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä -

OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY Engineering Physics

oml ORNL-6868 OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY Engineering Physics LOCK H * M D NJA Jt rim Or" and Mathematics Division ^ Progress Report for Period Ending December 31,1994 R. F. Sincovec, Director MANAGED BY LOCKHEED MARTIN ENERGY SYSTEMS, INC. FOR THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY UCI*13673 {36 W5) This report has been reproduced directly from the ilabie copy. Available to DOE and DOE contractors from the Scientific and Techni- cal Information, P.O. Box 62, Oak Ridge, TN 37> s available from (615) 576-8401, FTS 626-8401. Available to the public from the National Teci rmation Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Rd.,; d, VA 22161. This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, com• pleteness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process dis• closed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily consti• tute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. ORNL-6868 Engineering Physics and Mathematics Division ENGINEERING PHYSICS AND MATHEMATICS DIVISION PROGRESS REPORT FOR PERIOD ENDING DECEMBER 31, 1994 R. -

“Dropping the A-Bomb on Cities Was Mistake”—Father of Health Physics (As Published in the Oak Ridger’S Historically Speaking Column the Week of June 29, 2020)

“Dropping the A-bomb on cities was mistake”—Father of Health Physics (As published in The Oak Ridger’s Historically Speaking column the week of June 29, 2020) A friend and fellow historian, Alex Wellerstein, has just written in his blog, Restricted Data, The Nuclear Secrecy Blog, an entry entitled, What journalists should know about the atomic bombings. In this blog entry he notes that as we approach the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki we will surely see increased emphasis in the news regarding the atomic bombs. This is understandable and especially so in Oak Ridge, Los Alamos and Hanford. While my focus on Oak Ridge history in Historically Speaking may vary from time to time, the atomic bombs and what has resulted from the nuclear age over the years is never far from my mind. In these articles researched and written by Carolyn Krause, I am attempting to bring Historically Speaking readers perspectives that might well not normally be expressed. Not that I intend to alter your thinking regarding the use of the atomic bombs, as generally each of us have made our decision already. However, seeing the issue from different perspectives is worthwhile. For example, this particular article features comments and perspectives of Karl Z. Morgan. Some of you may even have known him. If that is the case, you likely already know his opinions. If you are being introduced to him for the first time reading this, it will be good for you to appreciate his perspective, even if you disagree with his conclusions. -

Footnotes for ATOMIC ADVENTURES

Footnotes for ATOMIC ADVENTURES Secret Islands, Forgotten N-Rays, and Isotopic Murder - A Journey into the Wild World of Nuclear Science By James Mahaffey While writing ATOMIC ADVENTURES, I tried to be careful not to venture off into subplots, however interesting they seemed to me, and keep the story flowing and progressing at the right tempo. Some subjects were too fascinating to leave alone, and there were bits of further information that I just could not abandon. The result is many footnotes at the bottom of pages, available to the reader to absorb at his or her discretion. To get the full load of information from this book, one needs to read the footnotes. Some may seem trivia, but some are clarifying and instructive. This scheme works adequately for a printed book, but not so well with an otherwise expertly read audio version. Some footnotes are short enough to be inserted into the audio stream, but some are a rambling half page of dense information. I was very pleased when Blackstone Audio agreed wholeheartedly that we needed to include all of my footnotes in this version of ATOMIC ADVENTURES, and we came up with this added feature: All 231 footnotes in this included text, plus all the photos and explanatory diagrams that were included in the text. I hope you enjoy reading some footnotes while listening to Keith Sellon-Wright tell the stories in ATOMIC ADVENTURES. James Mahaffey April 2017 2 Author’s Note Stories Told at Night around the Glow of the Reactor Always striving to beat the Atlanta Theater over on Edgewood Avenue, the Forsyth Theater was pleased to snag a one-week engagement of the world famous Harry Houdini, extraordinary magician and escape artist, starting April 19, 1915.1 It was issued an operating license, no. -

Article Thermonuclear Bomb 5 7 12

1 Inexpensive Mini Thermonuclear Reactor By Alexander Bolonkin [email protected] New York, April 2012 2 Article Thermonuclear Reactor 1 26 13 Inexpensive Mini Thermonuclear Reactor By Alexander Bolonkin C&R Co., [email protected] Abstract This proposed design for a mini thermonuclear reactor uses a method based upon a series of important innovations. A cumulative explosion presses a capsule with nuclear fuel up to 100 thousands of atmospheres, the explosive electric generator heats the capsule/pellet up to 100 million degrees and a special capsule and a special cover which keeps these pressure and temperature in capsule up to 0.001 sec. which is sufficient for Lawson criteria for ignition of thermonuclear fuel. Major advantages of these reactors/bombs is its very low cost, dimension, weight and easy production, which does not require a complex industry. The mini thermonuclear bomb can be delivered as a shell by conventional gun (from 155 mm), small civil aircraft, boat or even by an individual. The same method may be used for thermonuclear engine for electric energy plants, ships, aircrafts, tracks and rockets. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- Key words: Thermonuclear mini bomb, thermonuclear reactor, nuclear energy, nuclear engine, nuclear space propulsion. Introduction It is common knowledge that thermonuclear bombs are extremely powerful but very expensive and difficult to produce as it requires a conventional nuclear bomb for ignition. In stark contrast, the Mini Thermonuclear Bomb is very inexpensive. Moreover, in contrast to conventional dangerous radioactive or neutron bombs which generates enormous power, the Mini Thermonuclear Bomb does not have gamma or neutron radiation which, in effect, makes it a ―clean‖ bomb having only the flash and shock wave of a conventional explosive but much more powerful (from 1 ton of TNT and more, for example 100 tons). -

B Reactor's 60Th Anniversary, by Richard Rhodes

WashingtonHistory.org HISTORY COMMENTARY Hanford and History: B Reactor's 60th Anniversary By Richard Rhodes COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History, Fall 2006: Vol. 20, No. 3 Many people know the history of the Hanford Engineer Works well; some have lived it. I know it as a historian. I wrote about it in my book, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, and would have written more, but I simply did not have room. I treated plutonium production as a black box, inadvertently contributing to the myth that the atomic bomb was the work of 30 theoretical physicists at Los Alamos. More recently I have reviewed volumes of primary sources to refresh my memory of the heroic work carried out there between 1943 and 1945, so I think I can speak with some authority about it. I may even be able to clear up a mystery or two. Scientists at the Metallurgical Laboratory of the University of Chicago selected the site where plutonium would be produced for the first atomic bombs. Thirty-three-year-old Army Corps of Engineers colonel Franklin T. Matthias, known to his friends as "Fritz," wrote them into his diary after a meeting at DuPont’s home offices in Wilmington, Delaware, on December 14, 1942. The site needed to be spacious enough to accommodate a manufacturing area of approximately 12 by 16 miles, with no public highway or railroad nearer than 10 miles, no town of greater than 1,000 population nearer than 20 miles, an available water supply of at least 25,000 gallons per minute and an electrical supply of at least 100,000 kilowatts. -

Bob Farquhar

1 2 Created by Bob Farquhar For and dedicated to my grandchildren, their children, and all humanity. This is Copyright material 3 Table of Contents Preface 4 Conclusions 6 Gadget 8 Making Bombs Tick 15 ‘Little Boy’ 25 ‘Fat Man’ 40 Effectiveness 49 Death By Radiation 52 Crossroads 55 Atomic Bomb Targets 66 Acheson–Lilienthal Report & Baruch Plan 68 The Tests 71 Guinea Pigs 92 Atomic Animals 96 Downwinders 100 The H-Bomb 109 Nukes in Space 119 Going Underground 124 Leaks and Vents 132 Turning Swords Into Plowshares 135 Nuclear Detonations by Other Countries 147 Cessation of Testing 159 Building Bombs 161 Delivering Bombs 178 Strategic Bombers 181 Nuclear Capable Tactical Aircraft 188 Missiles and MIRV’s 193 Naval Delivery 211 Stand-Off & Cruise Missiles 219 U.S. Nuclear Arsenal 229 Enduring Stockpile 246 Nuclear Treaties 251 Duck and Cover 255 Let’s Nuke Des Moines! 265 Conclusion 270 Lest We Forget 274 The Beginning or The End? 280 Update: 7/1/12 Copyright © 2012 rbf 4 Preface 5 Hey there, I’m Ralph. That’s my dog Spot over there. Welcome to the not-so-wonderful world of nuclear weaponry. This book is a journey from 1945 when the first atomic bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert to where we are today. It’s an interesting and sometimes bizarre journey. It can also be horribly frightening. Today, there are enough nuclear weapons to destroy the civilized world several times over. Over 23,000. “Enough to make the rubble bounce,” Winston Churchill said. The United States alone has over 10,000 warheads in what’s called the ‘enduring stockpile.’ In my time, we took care of things Mano-a-Mano. -

The Los Alamos Thermonuclear Weapon Project, 1942-1952

Igniting The Light Elements: The Los Alamos Thermonuclear Weapon Project, 1942-1952 by Anne Fitzpatrick Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY STUDIES Approved: Joseph C. Pitt, Chair Richard M. Burian Burton I. Kaufman Albert E. Moyer Richard Hirsh June 23, 1998 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Nuclear Weapons, Computing, Physics, Los Alamos National Laboratory Igniting the Light Elements: The Los Alamos Thermonuclear Weapon Project, 1942-1952 by Anne Fitzpatrick Committee Chairman: Joseph C. Pitt Science and Technology Studies (ABSTRACT) The American system of nuclear weapons research and development was conceived and developed not as a result of technological determinism, but by a number of individual architects who promoted the growth of this large technologically-based complex. While some of the technological artifacts of this system, such as the fission weapons used in World War II, have been the subject of many historical studies, their technical successors -- fusion (or hydrogen) devices -- are representative of the largely unstudied highly secret realms of nuclear weapons science and engineering. In the postwar period a small number of Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory’s staff and affiliates were responsible for theoretical work on fusion weapons, yet the program was subject to both the provisions and constraints of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission, of which Los Alamos was a part. The Commission leadership’s struggle to establish a mission for its network of laboratories, least of all to keep them operating, affected Los Alamos’s leaders’ decisions as to the course of weapons design and development projects. -

Starpower: the US and the International Quest for Fusion Energy

Appendix B Other Approaches to Fusion The main body of this report has discussed magnetic The issues addressed by inertial confinement fusion confinement fusion, the approach to controlled fusion research in the United States concern the individual that the worldwide programs emphasize most heav- targets containing the fusion fuel; the input energy ily. However, two other approaches to fusion are also sources, called drivers, that heat and compress these being investigated. All three approaches are based on targets; and the mechanism by which energy from the the same fundamental physical process, in which the driver is delivered–or coupled–into the target. Due nuclei of light isotopes, typically deuterium and tri- to the close relationship between inertial confinement tium, release energy by fusing together to form heav- fusion target design and thermonuclear weapon de- ier isotopes. Some of the technical issues are similar sign, inertial confinement fusion research is funded among all the fusion approaches, such as mechanisms by the nuclear weapons activities portion of the De- for recovering energy and breeding tritium fuel. How- partment of Energy’s (DOE’s) budget. Inertial confine- ever, compared to magnetic confinement, the two ap- ment research is conducted largely at nuclear weap- proaches discussed below create the conditions nec- ons laboratories; its near-term goals are dedicated essary for fusion to occur in very different ways, and largely to military, rather than energy applications, and some substantially different science and technology a substantial portion of this research is classified. issues emerge in each case. There are two near-term military applications of in- ertial confinement fusion—one actual and one not yet Inertial Confinement Fusion1 realized. -

Hoyt S. Vandenberg, the Life of a General N/A 5B

20050429 031 PAGE Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, igathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports 1(0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. t. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 2000 na/ 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Hoyt S. Vandenberg, the life of a general n/a 5b. GRANT NUMBER n/a 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER n/a 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Meilinger, Phillip S n/a 5e. TASK NUMBER n/a 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER n/a 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER Air Force History Support Office 3 Brookley Avenue Box 94 n/a Boiling AFB DC 20032-5000 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSOR/MONITOR'S ACRONYM(S) n/a n/a 11.