SYON ABBEY SOCIETY Newsletter Issue 1, Fall 2010 Issue Editor: Laura Saetveit Miles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYON the Thames Landscape Strategy Review 3 3 7

REACH 11 SYON The Thames Landscape Strategy Review 3 3 7 Landscape Character Reach No. 11 SYON 4.11.1 Overview 1994-2012 • There has been encouraging progress in implementing Strategy aims with the two major estates that dominate this reach, Syon and Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. • Syon has re-established its visual connection with the river. • Kew’s master-planning initiatives since 2002 (when it became a World Heritage Site) have recognised the key importance of the historic landscape framework and its vistas, and the need to address the fact that Kew currently ‘turns its back on the river’. • The long stretch of towpath along the Old Deer Park is of concern as a fl ood risk for walkers, with limited access points to safe routes. • Development along the Great West Road is impacting long views from within Syon Park. • Syon House and grounds: major development plan, including re- instatement of Capability Brown landscape: re-connection of house with river (1997), opening vista to Kew Gardens (1996), re-instatement of lakehead in pleasure grounds, restoration of C18th carriage drive, landscaping of car park • Re-instatement of historic elements of Old Deer Park, including the Kew Meridian, 1997 • Kew Vision, launched, 2008 • Kew World Heritage Site Management Plan and Kew Gardens Landscape Masterplan 2012 • Willow spiling and tree management along the Kew Ha-ha • Invertebrate spiling and habitat creation works Kew Ha-ha. • Volunteer riverbank management Syon, Kew LANDSCAPE CHARACTER 4.11.2 The Syon Reach is bordered by two of the most signifi cant designed landscapes in Britain. Royal patronage at Richmond and Kew inspired some of the initial infl uential works of Bridgeman, Kent and Chambers. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early M

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Sara Victoria Torres 2014 © Copyright by Sara Victoria Torres 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia by Sara Victoria Torres Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Christine Chism, Co-chair Professor Lowell Gallagher, Co-chair My dissertation, “Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia,” traces the legacy of dynastic internationalism in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and early-seventeenth centuries. I argue that the situated tactics of courtly literature use genealogical and geographical paradigms to redefine national sovereignty. Before the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, before the divorce trials of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon in the 1530s, a rich and complex network of dynastic, economic, and political alliances existed between medieval England and the Iberian kingdoms. The marriages of John of Gaunt’s two daughters to the Castilian and Portuguese kings created a legacy of Anglo-Iberian cultural exchange ii that is evident in the literature and manuscript culture of both England and Iberia. Because England, Castile, and Portugal all saw the rise of new dynastic lines at the end of the fourteenth century, the subsequent literature produced at their courts is preoccupied with issues of genealogy, just rule, and political consent. Dynastic foundation narratives compensate for the uncertainties of succession by evoking the longue durée of national histories—of Trojan diaspora narratives, of Roman rule, of apostolic foundation—and situating them within universalizing historical modes. -

The Geoarchaeology of Past River Thames Channels at Syon Park, Brentford

THE GEOARCHAEOLOGY OF PAST RIVER THAMES CHANNELS AT SYON PARK, BRENTFORD Jane Corcoran, Mary Nicholls and Robert Cowie SUMMARY lakes created during the mid-18th century (discussed later). The western lake extends Geoarchaeological investigations in a shallow valley in from the Isleworth end of the park to the Syon Park identified two superimposed former channels main car park for both Syon House and the of the River Thames. The first formed during the Mid Hilton London Syon Park Hotel (hereafter Devensian c.50,000 bp. The second was narrower and the hotel site), while the other lies to the formed within the course of the first channel at the end north-east near the Brentford end of the of the Late Devensian. Both would have cut off part of park. The south-west and north-east ends the former floodplain, creating an island (now occupied of the arc are respectively centred on NGR by Syon House and part of its adjacent gardens and 516650 176370 and 517730 177050 (Fig 1). park). The later channel silted up early in the Holocene. In dry conditions part of the palaeochannel The valley left by both channels would have influenced may be seen from the air as a dark cropmark human land use in the area. During the Mesolithic the on the south-east side of the west lake and is valley floor gradually became dryer, although the area visible, for example, on an aerial photograph continued to be boggy and prone to localised flooding till taken in August 1944. modern times, leaving the ‘island’ as a distinct area of This article presents a summary of the geo- higher, dryer land. -

Kuml 2019 Kuml 2019

KUML 2019 KUML 2019 Årbog for Jysk Arkæologisk Selskab With summaries in English I kommission hos Aarhus Universitetsforlag 111737_kuml-2019_r1_.indd 3 25/10/2019 11.15 Afviklingen af de middelalderlige klostre i Danmark og Nordtyskland AF HANS KRONGAARD KRISTENSEN Fra dansk side har der indenfor klosterforskningen været stor interesse for grundlæggelsen af landets mange forskellige klostre. Mindre interesse har knyt- tet sig til deres afvikling. På én måde kan man naturligvis sige, at klosterlivet sluttede med Reformationen, men i det mindste forsvandt bygningerne ikke med et snuptag. Tværtimod er der en kompliceret afvikling, som på mange måder er individuel for de enkelte klostre.1 Afviklingen, nedlæggelsen og om- bygningerne af klosterbygningerne er dog uhyre væsentlig for mulighederne for gennem arkæologi og bygningsarkæologi at få kendskab til klostrenes ud- formning i middelalderen, hvor de var i brug. Nu hvor vi er begyndt at fejre 500-året for den lutherske Reformation, kunne dette være en anledning til at se på afviklingen af klostrene. Og i sammenhæng hermed kan det også være relevant at se på vilkårene uden for Danmark som i Nordtyskland, der nogen- lunde samtidig overgik til den luthersk evangeliske kirkestruktur uden klostre. Inden for klostervæsnet er det i grunden uhyre sjældent, at man drager sammenligninger mellem Danmark og Nordtyskland – her har man normalt kikket længere væk, hvilket igen hænger sammen med interessen for grund- læggelsestiden, hvor indflydelsen er kommet fra steder som England, Frankrig og Rhinområdet. Disse områder er dog ikke brugbare til sammenligninger om klostrene i forhold til Reformationen. I England skete der nemlig en voldsom forandring med The Suppression of the Monasteries fra 1536-40. -

Digheds Og Den Hellige Martyr Lucius' Kirke

b k 5 \ DET KONGELIGE BIBLIOTEK DA 1.-2.S 34 II 8° 1 1 34 2 8 02033 9 ft:-' W/' ; ■■ pr* r ! i L*•' i * •! 1 l* 1*. ..«/Y * ' * !■ k ; s, - r*r ' •t'; ;'r rf’ J ■{'ti i ir ; • , ' V. ■ - •'., ■ • xOxxvX: ■ yxxf xXvy.x :■ ■ -XV' xxXX VY, XXX YXYYYyØVø YY- afe ■ .v;X' p a V i %?'&ø :■" \ . ' :•!■• ,-,,r*-„f.>/r'. .. ‘m.;.;- • 7.- .; 7.. \ v ;»WV X '• • ø •'>; ^/■•.,:. i ■-/.. ,--.v ■,,'--- ;X:/. - V '-■■. <V;:S'. ■ V ;>:X.>. - . / : r- :. • • • v •'•<.•.'•„.'«;•••■ • : ø ø r - 0 0 ^ 0 ^ , ' . i* n ‘-:---yri ' *•1 Y v - ^ y ' xv • v^o^.1. •’". '.. ' ^ ^ - ■ ■ *: . ‘4 V • : Vi.'-* ' •• , -py » » r S * . ., v- - Y,■ x.: ■■■ '/ ■. '-^;-v•:■■'•:. I , /■ ... \ < y : - j _ _ ^ . '. • vV'V'-WC'/:i .. • .' - '■V ^ -V X X i ■:•*'• -fåk=, ’å«! r “\ > VéS' V: m;. ^ S -T 'l ' é Æ rs^l K»s£-^v;å8gSi;.:v ,V i: ,®%R m r t m •'. * ‘ • iW . - ' * •’ ' ''*- ’-' - - • • 7« ' - “'' ' ’ i ' l ø ^ i j : j I 0 - + ! f- .. i 1 v s . j.. •; ■''■ - - . ' • < •‘ . ( . :/Æ m .‘-\ ^ • • v ; ;-• ,ti , ’- É p Æ f s . - f./'T-i :\ . :■.:érijid \*| ^ i ? S \ ■!- X.-3 I M«i; .•• ./;,X $ii«M c '>^w xhr-.vX . - " ' . v - x ^ P 3X.V ,v '■'/■ :■ 1 ■'■■I ; /# 1'..: \ ; . ?.. >>■>. ;; !a - ; : i : ■ •■ vrd-^i.■■■: v .^ > ;', v \ . ; ^ .1. .,*.-• •-• — » . ‘ -,-\ ■'£ vV7 -u-' "*■- ;' ' v ' ;i'»1 '••-■^ .VV ’ i rr^— 7— -X r- ••r-’arjr . • 4 i.1-’ 1 ^ • — ^.ft ... <t ' i v - ^ '-» 1 ■ .■ ■ T* • \ > .• •■,.■ ;- : . ; . ^ ' ■ I M r^-^Tør^r- 0 "^: ør.:,ø^n>w^: ■■'^nw'<$:fi&rrTi A w ; :• v ' .:”. 1 i.- V V ' ' «‘v >»?•-•.-. ' -...■i iWl••••. ? .•”■ /•<. • ^ ■ •* ' '/■:■ , '■'/■ ,- ' . •> . ^ . ’ • ,v :■ ■?. • ;■ • . ‘ ' ' ' ' . •.i* L*4 V v’ f. * v-.-iV-, iU ' . -

A Brief History of Medieval Monasticism in Denmark (With Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia)

religions Article A Brief History of Medieval Monasticism in Denmark (with Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia) Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig Jakobsen Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics, University of Copenhagen, 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] Abstract: Monasticism was introduced to Denmark in the 11th century. Throughout the following five centuries, around 140 monastic houses (depending on how to count them) were established within the Kingdom of Denmark, the Duchy of Schleswig, the Principality of Rügen and the Duchy of Estonia. These houses represented twelve different monastic orders. While some houses were only short lived and others abandoned more or less voluntarily after some generations, the bulk of monastic institutions within Denmark and its related provinces was dissolved as part of the Lutheran Reformation from 1525 to 1537. This chapter provides an introduction to medieval monasticism in Denmark, Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia through presentations of each of the involved orders and their history within the Danish realm. In addition, two subchapters focus on the early introduction of monasticism to the region as well as on the dissolution at the time of the Reformation. Along with the historical presentations themselves, the main and most recent scholarly works on the individual orders and matters are listed. Keywords: monasticism; middle ages; Denmark Citation: Jakobsen, Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig. 2021. A Brief For half a millennium, monasticism was a very important feature in Denmark. From History of Medieval Monasticism in around the middle of the 11th century, when the first monastic-like institutions were Denmark (with Schleswig, Rügen and introduced, to the middle of the 16th century, when the last monasteries were dissolved Estonia). -

The 'Long Reformation' in Nordic Historical Research

1 The ‘long reformation’ in Nordic historical research Report to be discussed at the 28th Congress of Nordic Historians, Joensuu 14-17 August 2014 2 Preface This report is written by members of a working group called Nordic Reformation History Working Group, that was established as a result of a round table session on the reformation at the Congress of Nordic Historians in Tromsø in Norway in August 2011. The purpose of the report is to form the basis of discussions at a session on “The ‘long reformation’ in Nordic historical research” at the Congress of Nordic Historians in Joensuu in Finland in August 2014. Because of its preliminary character the report must not be circulated or cited. After the congress in Joensuu the authors intend to rework and expand the report into an anthology, so that it can be published by an international press as a contribution from the Nordic Reformation History Working Group to the preparations for the celebration in 2017 of the 500 years jubilee of the beginning of the reformation. Per Ingesman Head of the Nordic Reformation History Working Group 3 Table of contents Per Ingesman: The ’long reformation’ in Nordic historical research – Introduction – p. 4 Otfried Czaika: Research on Reformation and Confessionalization – Outlines of the International Discourse on Early Modern History during the last decades – p. 45 Rasmus Dreyer and Carsten Selch Jensen: Report on Denmark – p. 62 Paavo Alaja and Raisa Maria Toivo: Report on Finland – p. 102 Hjalti Hugason: Report on Iceland – (1) Church History – p. 138 Árni Daníel Júlíuson: Report on Iceland – (2) History – p. -

01395 513340

Canon Paul Cummins The Presbytery, Radway, Sidmouth, EX10 8TW 01395 513340 Church of The Most Precious Blood Retired Priest: Fr Patrick Kilgarriff Exeter Hospital Chaplain: Canon John Deeny 01392 272815 [email protected] www.churchofthemostpreciousblood SIXTH WEEK OF EASTER C PSALTER 2 sidmouth.co.uk @SidmthRCParish Saturday 5:30pm Vigil Mass Sunday 10:30am Sixth Sunday of Easter People of the Parish Monday 10:00am Memorial Mass of St Athanasius Tuesday 6:00pm Feast of St Philip and St James the Apostles Rita Bradley RIP Wednesday 10:00am Feast of the English Martyrs Agnes Evans RIP Thursday 9:00am Memorial Mass of St Richard Reynolds Jane Rodgers RIP Friday 10:00am Easter Weekday Mass Confessions After weekday Mass or by appointment Let us keep in our prayers those who are sick and housebound in our parish including Margaret Perrigo, Joyce Long, Connie Loebell, Mary Wallace, Steven & Anne Rampersad, Peggy Smith, Rebecca Warren-Heys, Kay Evans, Joyce Prankard, Clifford Brown, Christopher Brown, Eileen Brown, Margaret & Ted Ford, Suzanne Hosker, George Mullen, Catherine Whister, Sister Bernadette and Bernie Coleman. Welcome to all our visitors. We hope you have a lovely stay in Sidmouth. Please join us in the hall after Sunday Mass where sherry, coffee, tea and biscuits will be served to celebrate the month of Mary. For children there will be ice-cream sodas and a special Children’s Cookie Corner. This week’s Sunday Service is being broadcast by BBC radio Devon from Our Lady and St Patrick’s school in Teignmouth. Featuring Fr Mark Skelton, the head teacher Sarah Baretto,and seven children from year six talking about why and how they pray. -

“Still More Glorifyed in His Saints and Spouses”: the English Convents in Exile and the Formation of an English Catholic Identity, 1600-1800 ______

“STILL MORE GLORIFYED IN HIS SAINTS AND SPOUSES”: THE ENGLISH CONVENTS IN EXILE AND THE FORMATION OF AN ENGLISH CATHOLIC IDENTITY, 1600-1800 ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History ____________________________________ By Michelle Meza Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Gayle K. Brunelle, Chair Professor Robert McLain, Department of History Professor Nancy Fitch, Department of History Summer, 2016 ABSTRACT The English convents in exile preserved, constructed, and maintained a solid English Catholic identity in three ways: first, they preserved the past through writing the history of their convents and remembering the hardships of the English martyrs; that maintained the nuns’ continuity with their English past. Furthermore, producing obituaries of deceased nuns eulogized God’s faithful friends and provided an example to their predecessors. Second, the English nuns cultivated the present through the translation of key texts of English Catholic spirituality for use within their cloisters as well as for circulation among the wider recusant community to promote Franciscan and Ignatian spirituality. English versions of the Rule aided beginners in the convents to faithfully adhere to monastic discipline and continue on with their mission to bring English Catholicism back to England. Finally, as the English nuns looked toward the future and anticipated future needs, they used letter-writing to establish and maintain patronage networks to attract novices to their convents, obtain monetary aid in times of disaster, to secure patronage for the community and family members, and finally to establish themselves back in England in the aftermath of the French Revolution and Reign of Terror. -

LF Katalog 2021 Web.Pdf

2021 Velkommen til Lolland-FalsterWelcome & Willkommen - De danske sydhavsøer DANSK | ENGLISH | DEUTSCH FOTO: MARIELYST STRAND MARIELYST FOTO: Content INDHOLD Inhalt Brian Lindorf Hansen Destinationschef/ Head of Tourism Visit Lolland-Falster Dodekalitten Gastronomi Maribo Gedser Gastronomy Gastronomie John Brædder Borgmester/Mayor/ Bürgermeister Guldborgsund Kommune Nysted Nykøbing Aktiv Naturens Falster ferie perler Active holiday Aktivurlaub Nature’s gems Øhop Holger Schou Rasmussen Die Perlen der Natur Borgmester/Mayor/ Bürgermeister Island hop Lolland Kommune Marielyst Sakskøbing Inselhopping Nakskov Stubbekøbing 2 visitlolland-falster.dk #LollandFalster 3 Enø ByEnø By j j 38 38 SmidSmstruidpstrup Skov Skov KirkehKiavrkehn avn BasnæsBasnæs Omø O- Smtiøgs-nSætigssnæs StoreStore PræsPrtøæs Fjtøor FjdordFeddetFeddet (50 m(i5n0) min) VesterVester RøttingRøttie nge ØREN ØREN KarrebKarrebæksmindeæksminde KYHOLMKYHOLM EgesboEgesrgborg HammHaermmer FrankeklFrinant keklint BroskoBrvoskov NordstNorardndstrand OmøOm By ø ByOMOMØ Ø BugtBugt HammHaermm- 265er- 265 STOREHSTOREHOLM OLM DybsDyø bsFjorø Fjdord TorupTorup EngelholEngemlhol209m 209 RingRing RisbyRisby BårsBårse e MADERNMAEDERNE Hov Hov NysøNysø Hou FyHor u Fyr RoneklinRonet klint DYBSDYØBSØ KostræKodestræde 39 39 PræsPrtøæstø VesterVesterØsterØster LundbyLund- by- BønsBøvignsvig PrisskProvisskov gaardgaard LohalsLohalsStigteSthaigvetehave AmbæAmk bæk ØsterØsUgteler bjUgerlegbjerg Gl. Gl. TubæTuk bæk JungJus- ngs- StigteSthaigvetehave SvinøSv Stinrandø Strand FaksinFageksingeHuseHuse -

Name and Place

Vibeke Dalberg NAME AND PLACE Ten essays on the dynamics of place-names I Navnestudier udgivet af Afdeling for Navneforskning Nr. 40 II VIBEKE DALBERG III IV Vibeke Dalberg NAME AND PLACE Ten essays on the dynamics of place-names Edited and translated by Gillian Fellows-Jensen, Peder Gammeltoft, Bent Jørgensen and Berit Sandnes on the occasion of Vibeke Dalberg’s 70th birthday, August 22nd 2008 Department of Scandinavian Research Name Research Section Copenhagen 2008 V Fotografisk, mekanisk eller anden gengivelse af denne bog eller dele heraf er ikke tilladt ifølge gældende dansk lov om ophavsret. © Afdeling for Navneforskning, Nordisk Forskningsinstitut Det Humanistiske Fakultet Københavns Universitet Photo by Rob Rentenaar Freely available internet publication, the Faculty of Humanities, University of Copenhagen Copenhagen 2008 ISBN 978-87-992447-1-3 VI Foreword Vibeke Dalberg has been studying place-names and personal names throughout a long and active life of scholarly research. The material she has employed has generally been Danish but the perspective of the research and the scope of its results have normally been of rele- vance for the whole of the Germanic language area. Through her yearlong involvement in ICOS, Vibeke Dalberg has become well- known and highly respected as an onomastician. For those who do not read Danish, however, much of her work and some of her most significant papers have remained a closed book. To remedy this state of affairs, friends and colleagues at Vibeke’s former place of work, the Name Research Section at the University of Copenhagen, have wished to mark her 70th birthday by arranging for ten important papers to be translated into English. -

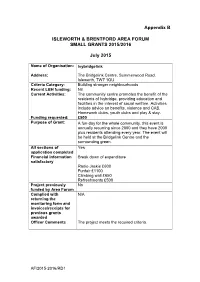

Small Grants Report

Appendix B ISLEWORTH & BRENTFORD AREA FORUM SMALL GRANTS 2015/2016 July 2015 Name of Organisation: Ivybridgelink Address: The Bridgelink Centre, Summerwood Road, Isleworth, TW7 1QU Criteria Category: Building stronger neighbourhoods Recent LBH funding: Nil Current Activities: The community centre promotes the benefit of the residents of Ivybridge, providing education and facilities in the interest of social welfare. Activities include advice on benefits, violence and CAB. Homework clubs, youth clubs and play & stay. Funding requested: £500 Purpose of Grant: A fun-day for the whole community, this event is annually recurring since 2000 and they have 2000 plus residents attending every year. The event will be held at the Bridgelink Centre and the surrounding green. All sections of Yes application completed Financial information Break down of expenditure satisfactory Radio Jackie £600 Funfair £1100 Climbing wall £650 Refreshments £500 Project previously No funded by Area Forum Complied with N/A returning the monitoring form and invoices/receipts for previous grants awarded Officer Comments The project meets the required criteria. AF/2015-2016/RD1 Name of Organisation: Our Lady of Sorrows and St Bridget’s Church Address: Memorial Square, 112 Twickenham Road, Isleworth TW7 6DL Criteria Category: Building stronger neighbourhoods Recent LBH funding: Nil Current Activities: Holding religious services such as christenings, funerals, marriages and baptisms. Hosting and helping to organise various weekly groups for disadvantaged people (including non-church members) e.g. older people, special needs, partially sighted, mental health drop-in. Funding requested: £500 Purpose of Grant: An open-air, ecumenical service of celebration and commemoration marking the 600th Anniversary of the Foundation of Syon Abbey for the Bridgettines, an order of religious people still existing today.