Temporary EU Labor Migrants and Housing Policy Challenges: Policy Differences Between Municipalities in Zuid-Holland and the Role of Private Actors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proces En Bestuurlijke Gesprekken Actualisatie Versie 19 Februari 2018

Proces en bestuurlijke gesprekken Actualisatie versie 19 februari 2018 Overleg Deelnemers Data Subregio Ambtenaren en medewerkers corporaties Week 5 Concept ABF subregio (overleg op ambtelijk niveau op maandag 5/2 of mail-consultatie) Gesprekken RIGO en verkenning Week 5 t/m week 13 gemeenten en corpo's handelingsperpectieven. Input concept ABF en informatieve tekst Week 6: Di 6 /2 (mits brief provincie dan binnen is) en concept agenda kick off Stuurgroep Wonen J. Versluijs (voorzitter - Vlaardingen) Week 6: Do 8/2 n Stelt ABF-rapport vast en A. van Tatenhove (Lansingerland) 15.00-17.00 uur informatieve tekst voor colleges J. de Leeuwe (Albrandswaard) Gemeente Vlaardingen zodat wethouders ruimte J.W. Mijnans (Nissewaard) B&W Kamer hebben voor accorderen R. Simons (Rotterdam) overdrachtsdocument en tk brief J. Blankenberg (Krimpen a.d. IJssel) gedeputeerde A. van Steenderen (Schiedam) Vaststellen als startdocumenten A. van Ettinger (Maaskoepel) om RIGO onderzoek op te E. van der Velden (projectleider) baseren: Peter Groeneweg (notulist) 1) Streefvoorraad totale voorraad en sociale voorraad conform midden doelgroep nu en straks 2) max spreidingsgerichte voorraad zonder dat er leegstand ontstaat 1e tussenrapportage RIGO Week 7: Di 13/2 (Mits (signalerend memo) subregionale trekkers allemaal voor de 12e gesproken zijn.) Bespreking signalerend memo (mits op Week 7: Di 13/2 tijd binnen) en ABF, informerende tekst voor colleges en brief gedeputeerde en — voorbereiding op kick off 22/2 Regiostaf Wonen (voorafgaand J. Versluijs (voorzitter - Vlaardingen) Week 7: Wo 14/2 aan de Regiotafel Wonen) P. Groeneweg (Rotterdam) 13.30-14.30 uur 1,0 uur E. van der Velden (projectleider) Gemeente Vlaardingen Kamer wethouder Versluijs Regiotafel Wonen Versluijs (voorzitter - Vlaardingen) Week 7: Wo 14/2 Tussenstap: Gedeputeerde Bom-Lemstra (eenmalig) 16.00-17.30 uur » Overheidsakkoord A. -

Ontwerp-Besluit

ONTWERP OMGEVINGSVERGUNNING VOOR DE ACTIVITEITEN UITVOEREN WERK OF WERKZAAMHEDEN, AFWIJKEN VAN HET BESTEMMINGSPLAN EN UITWEG Kenmerk: W20160091 Burgemeester en wethouders van de gemeente Kaag en Braassem; gelezen de op 31 maart 2016 ingekomen aanvraag van TenneT TSO B.V., Utrechtseweg 310, 6812 AR te Arnhem, voor een omgevingsvergunning voor de activiteiten uitvoeren werk of werkzaamheden, afwijken van het bestemmingsplan en uitweg, ten behoeve van het verplaatsen van een toegangsweg en een uitweg bij het realiseren van een hoogspanningsverbinding voor het Randstad 380 kV-project, op het perceel Provincialeweg 2 te Rijpwetering; gelet op het bepaalde in artikel 2.1, eerste lid, sub b en artikel 2.11 Wet algemene bepalingen omgevingsrecht (Wabo) (activiteit uitvoeren werk of werkzaamheden); gelet op het bepaalde in artikel 2.1, eerste lid, sub c en artikel 2.12, eerste lid, sub a, sublid 3° Wabo (activiteit afwijken); gelet op het bepaalde in artikel 2.2, eerste lid, sub e en artikel 2.18 Wabo juncto artikel 2.1.5.3 van de Algemene Plaatselijke Verordening Kaag en Braassem 2009 (APV) (activiteit uitweg); overwegende ten aanzien van de procedure en de termijnstelling: dat in artikel 20a, eerste lid, van de Elektriciteitswet 1998 is bepaald dat op de besluitvorming voor dit project de rijkscoördinatieregeling als bedoeld in artikel 3.35 van de Wet ruimtelijke ordening (Wro) van toepassing is; dat de besluiten die nodig zijn voor de hoogspanningsverbinding Randstad 380kV Beverwijk-Bleiswijk (Noordring) gezamenlijk worden voorbereid en deze -

Indeling Van Nederland in 40 COROP-Gebieden Gemeentelijke Indeling Van Nederland Op 1 Januari 2019

Indeling van Nederland in 40 COROP-gebieden Gemeentelijke indeling van Nederland op 1 januari 2019 Legenda COROP-grens Het Hogeland Schiermonnikoog Gemeentegrens Ameland Woonkern Terschelling Het Hogeland 02 Noardeast-Fryslân Loppersum Appingedam Delfzijl Dantumadiel 03 Achtkarspelen Vlieland Waadhoeke 04 Westerkwartier GRONINGEN Midden-Groningen Oldambt Tytsjerksteradiel Harlingen LEEUWARDEN Smallingerland Veendam Westerwolde Noordenveld Tynaarlo Pekela Texel Opsterland Súdwest-Fryslân 01 06 Assen Aa en Hunze Stadskanaal Ooststellingwerf 05 07 Heerenveen Den Helder Borger-Odoorn De Fryske Marren Weststellingwerf Midden-Drenthe Hollands Westerveld Kroon Schagen 08 18 Steenwijkerland EMMEN 09 Coevorden Hoogeveen Medemblik Enkhuizen Opmeer Noordoostpolder Langedijk Stede Broec Meppel Heerhugowaard Bergen Drechterland Urk De Wolden Hoorn Koggenland 19 Staphorst Heiloo ALKMAAR Zwartewaterland Hardenberg Castricum Beemster Kampen 10 Edam- Volendam Uitgeest 40 ZWOLLE Ommen Heemskerk Dalfsen Wormerland Purmerend Dronten Beverwijk Lelystad 22 Hattem ZAANSTAD Twenterand 20 Oostzaan Waterland Oldebroek Velsen Landsmeer Tubbergen Bloemendaal Elburg Heerde Dinkelland Raalte 21 HAARLEM AMSTERDAM Zandvoort ALMERE Hellendoorn Almelo Heemstede Zeewolde Wierden 23 Diemen Harderwijk Nunspeet Olst- Wijhe 11 Losser Epe Borne HAARLEMMERMEER Gooise Oldenzaal Weesp Hillegom Meren Rijssen-Holten Ouder- Amstel Huizen Ermelo Amstelveen Blaricum Noordwijk Deventer 12 Hengelo Lisse Aalsmeer 24 Eemnes Laren Putten 25 Uithoorn Wijdemeren Bunschoten Hof van Voorst Teylingen -

De Beste Zorg Voor U, Thuis

Informatie over: ontdek. Thuiszorg De beste zorg voor u, thuis. Zo goed en zelfstandig mogelijk leven in uw eigen vertrouwde omgeving. Laurens biedt alle zorg die u hierbij nodig heeft. meer dan zorg Langer thuis wonen. De één redt het zelf, de ander met hulp van buitenaf. Heeft u professionele hulp nodig? Laurens geeft u de juiste zorg en ondersteuning aan huis. Wij zijn 24 uur per dag, 7 dagen per week, bereikbaar en zetten zorg in wanneer u dit wenst. Voor korte of langere tijd. Wij kennen uw buurt Laurens heeft ruim 100 thuiszorgteams in Rotterdam, Capelle aan den IJssel, Lansingerland, Barendrecht en Hoogvliet. Wij werken met kleine teams bestaande uit (wijk)verpleegkundigen en verzorgenden. Zo bent u verzekerd van vertrouwde gezichten. Onze teams zijn goed op de hoogte van de voorzieningen in uw wijk. Onze wijkverpleegkundige denkt met u en uw netwerk mee over oplossingen bij uw vragen over wonen, zorg en welzijn. Samen met onze zorgpartners Om u zo goed mogelijk te helpen, werkt uw thuiszorgteam nauw samen met huisartsen, specialisten, apothekers, vrijwilligers(organisaties) en andere maatschappelijke en gemeentelijke instanties. Mogelijkheden van zorg en ondersteuning bij u thuis Persoonlijke verzorging U krijgt ondersteuning bij dagelijkse handelingen zoals wassen en aan- en uitkleden. Waar mogelijk leert u bepaalde handelingen weer helemaal zelf te doen, met of zonder hulpmiddelen. Verpleging Als u verpleging thuis nodig heeft, dan zorgt de wijkverpleegkundige vanuit het thuiszorgteam hiervoor. Zij houdt uw gezondheid goed in de gaten en levert u de nodige zorg. Denk bijvoorbeeld aan het geven van injecties, het verzorgen van uw wond of het toedienen van sondevoeding. -

2017 Residents Langsingerland Bergschenhoek 30% 18,075 10.0% Berkel En Rodenrijs 50% 30,048 5.0% 100% 60,042

Health Center “Medisch Hart Bleiswijk “ Dorpstraat 3 in Bleiswijk (South Holland ) Muncipality “Lansingerland” The health center “Medische Hart Bleiswijk”, is Located in the city center of Bleiswijk situated in the former town hall (first stone laid in 1983). The "Bleiswijk Medical Heart" consists of a 12 room “Health Recovery” hotel approved by SNHZ (Association Dutch Recovery Hotel Standards and Requirements) “Stichting Nederlandse Herstellingsoorden en Zorghotels” , a service desk and a health center with the following specializations: Doctors Pratice “GGZ Delfland - GR1PP” Diet and sportadvice. Physiotherapy Practice for Lansingerland, Podotherapy Doctor Children physio therapy Child psychologist Natural Therapist Homecare organisation Skin Care Practice Homecare Shop Pharmacy Sport healthcare specialist Midwifery Center Lansingerland Demographics: The population between the ages of 35-55 years has grown sharply in recent years, but is now stabilizing. The number of age 65 plus has also risen steadily, and continues so that in the coming years there will be about 50% more in the age group 65 plus than now. %Population Polpulation Bleiswijk 20% 11,919 2017 Residents Langsingerland Bergschenhoek 30% 18,075 10.0% Berkel en Rodenrijs 50% 30,048 5.0% 100% 60,042 0.0% Copyright © 2017 Secerno All Rights Reserved Private and Confidential www.secerno-re.com Location Bleiswijk “district of Lansingerland”, is close to the cities of The Hague and Rotterdam. The "Bleiswijk Medical Heart" is located in the center of Bleiswijk, near supermarkets and public transport. There are 4 hospitals around Bleiswijk in the region. In the vicinity of the "MHB" is a “Laurens Woonzorg” location, that delivers long-term care for people from light to heavy ageing conditions relating to Alzheimers, Dementia, Physical/Phsychiatric conditions that may be due to old age or Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). -

Sociale Verschillen En Overeenkomsten in Zuid-Holland Stand Van Zaken, Trends En Ontwikkelingen

RIGO Research en Advies Woon- werk- en leefomgeving www.rigo.nl . Sociale verschillen en overeenkomsten in Zuid-Holland Stand van zaken, trends en ontwikkelingen De verantwoordelijkheid voor de inhoud berust bij RIGO. Het gebruik van cijfers en/of tek- sten als toelichting of ondersteuning in artikelen, scripties en boeken is toegestaan mits de bron duidelijk wordt vermeld. RIGO aanvaardt geen aansprakelijkheid voor drukfouten en/of andere onvolkomenheden. RIGO Research en Advies Woon- werk- leefomgeving www.rigo.nl . Sociale verschillen en overeenkomsten in Zuid-Holland Stand van zaken, trends en ontwikkelingen Opdrachtgever Contactpersoon M. Hekker Projectnummer P37370 Datum 21 september 2018 Auteurs André Buys; [email protected]; 020 522 11 73 Aafke Heringa; [email protected]; 020 522 11 25 . Sociale verschillen en overeenkomsten in Zuid-Holland Inhoud Samenvatting 7 Aanleiding en opzet van deze verkenning 10 Aanleiding en doel 10 Onderzoeksopzet en begrippenkader 10 Toelichting gebruikte figuren en indices 13 Sociale verschillen in Nederland 18 Historische scheidslijnen 18 Veranderende assen van verschil 19 Actuele verschillen in Nederland 21 Geografische en demografische context 26 Bevolkingsgroei 27 Bevolkingssamenstelling naar leeftijd 33 Bevolking naar migratieachtergrond 39 Grootte van het huishouden 43 Selectieve migratie 45 Sociaaleconomische verschillen 48 Inkomens 48 Bijstand en andere uitkeringen 51 Opleidingsniveau 54 Arbeidsparticipatie 59 Vermogen 61 Eigen woningbezit 63 Verschillen binnen gemeenten 69 Ontwikkeling -

Position Paper Greenport 2015-2018

Gemeente Lansingerland Position Paper Greenport 2015-2018 Auteur : Samir Amghar Afdeling: Team Economie, Onderwijs & Sport Datum : 24 maart 2015 Corsanummer : T14.19005 T14.18954 Inhoudsopgave 1. Inleiding 1.1 Aanleiding 3 1.2 Tweede glastuinbouwgemeente van Nederland 4 1.3 Lansingerlandse bedrijven aan de top 5 1.4 Leeswijzer 5 2. Uitdagingen sector 6 2.1 Inleiding 6 2.2 Mondialisering 6 2.3 Prijzen onder druk 6 2.4 Wetgeving 6 2.5 Energiekosten 7 2.6 Arbeid en imago: onbekend maakt onbemind 7 3. Speerpunten sector 8 3.1 Inleiding 8 3.2 Transitie naar een innovatieve Greenport 8 3.3 Krachten bundelen door samenwerking 8 3.4 Greenportsamenwerking nationaal speerpunt 9 3.5 Provincie Zuid-Holland 10 3.6 Regionale samenwerkingsverbanden 11 4. Actieprogramma Lansingerland 14 4.1 Inleiding 14 4.2 Economie & Ruimtelijke ontwikkeling 14 4.2.1 Internationale samenwerking 14 4.2.2 Bedrijven Investerings Zone 15 4.2.3 Stoppersnetwerk 15 4.2.4 Glastuinbouwbedrijvengebieden 15 4.2.5 Actielijst Economie & ruimtelijke ontwikkeling 17 4.3 Kennis, innovatie & scholing 18 4.3.1 Kennis & innovatie 18 4.3.2 Scholing 18 4.3.3 Actielijst kennis, innovatie & scholing 19 4.4 Milieu & duurzaamheid 21 4.4.1 Actielijst milieu & duurzaamheid 22 4.5 Bereikbaarheid & infrastructuur 23 4.5.1 Actielijst bereikbaarheid & infrastructuur 23 5. Aan de slag 24 Position Paper Greenport Pagina 2/24 T14.18954 1. Inleiding 1.1 Aanleiding Lansingerland behoort samen met de gemeenten Pijnacker-Nootdorp, Westland, Midden-Delfland, Leidschendam-Voorburg, Waddinxveen, Zuidplas en Barendrecht tot de Greenport 1 Westland-Oostland . -

2017 Zuid-Holland

lokale energie monitor 2017 ZUID-HOLLAND NAAR INHOUD COLOFON Uitgave april 2018 Inhoud Opdrachtgever: Provincie Zuid-Holland Onderzoeker: Anne Marieke Schwencke In opdracht van: HIER opgewekt 3 VOORWOORD De Lokale Energie Monitor is een initiatief 5 SAMENVATTING van Stichting HIER opgewekt. De monitor verschijnt jaarlijks en wordt in opdracht van HIER 6 1 INLEIDING opgewekt uitgevoerd door Anne Marieke Sch- wencke. Met ondersteuning van RVO en mede- 8 2 BURGERCOLLECTIEVEN werking van PBL, VNG en netbeheerders. 19 3 PRODUCTIE: COLLECTIEVE ZON Hiervoor o.a. is samengewerkt met regionale en landelijke partners: Siward Zomer (ODE 33 4 PRODUCTIE: COLLECTIEVE WIND Decentraal & REScoopNL, De Windvogel), Stichting Den Haag Duurzaam, Zuid-Hollandse 44 5 ENERGIEBESPARING, WARMTETRANSITIE coöperaties en bewonersinitiatieven. 55 6 LOKALE ENERGIE: MARKT 62 BIJLAGEN TERUG NAAR INHOUD Voorwoord Geachte lezer, Met gepaste trots bied ik u deze eerste monitor van de Zuid-Hollandse lokale energie-initiatieven aan. In onze Zuid-Hollandse energiestrategie is een van de onderdelen ‘samen aan de slag’. Wij kunnen vanachter ons bureau namelijk heel veel bedenken, maar het is altijd sterker als mensen in de wijk dat zelf doen. Dat ondersteunen we door een lerend netwerk in onze provincie op te richten en door de subsidieregeling “Lokale initiatieven”. Het doel van deze activiteiten is het vergroten van het draagvlak voor lokaal opgewekte en bespaarde energie. Deze eerste Zuid-Hollandse Lokale Energie Monitor laat goed zien hoeveel er al gaande is in onze provincie. Alleen al in Den Haag zijn meer dan 14 lokale initiatiefgroepen actief, waaronder 5 energie- coöperaties. We zijn trots op de windcoöperatie Deltawind, een van de grootste en oudste windcoöperaties van Nederland, die al bijna 40 jaar actief is in Zuid-Holland. -

ALGEMENE TOELICHTING Sinds Medio 2012 Vormen De Gemeenten

ALGEMENE TOELICHTING Sinds medio 2012 vormen de gemeenten Leidschendam-Voorburg, Wassenaar, Voorschoten, Lansingerland, Pijnacker-Nootdorp en Zoetermeer de arbeidsmarktregio Zuid-Holland Centraal. Een van de doelstellingen van het Actieplan Zuid-Holland Centraal (ZHC) is het versterken en harmoniseren van de werkgeversdienstverlening. De zes gemeenten streven in dat kader onder andere naar het zoveel mogelijk op elkaar afstemmen van de re-integratie instrumenten. Binnen de managementgroep werkgeversbenadering van de ZHC-gemeenten is de wens uitgesproken om regionaal het palet aan instrumenten dat accountmanagers bij de werkgeversbenadering kunnen inzetten af te stemmen. Belangrijk onderdeel is afstemming van de voorwaarden voor en de hoogte van de loonkostensubsidies Wet werk en bijstand (WWB). Het vaststellen van het re-integratiebeleid dient lokaal plaats te vinden. Het regionale voorstel ten aanzien van de loonkostensubsidies wordt daarom in het beleid van Pijnacker-Nootdorp opgenomen door middel van het vaststellen van de eerste wijziging Uitvoeringsbesluit re-integratie 2012 gemeente Pijnacker-Nootdorp. Ten opzichte van het oorspronkelijk uitvoeringsbesluit re-integratie 2012 betekent dit concreet aanpassing van artikel 2, zevende lid van het uitvoeringsbesluit re-integratie. In het oorspronkelijke uitvoeringsbesluit re- integratie is een eenmalige loonkostensubsidie van € 4.500 opgenomen bij een dienstverband van minimaal 6 maanden. Met deze eerste wijziging wordt om dit gewijzigd in: - een eenmalige loonkostensubsidie van € 4.000 in de situatie van een halfjaarcontract - een eenmalige loonkostensubsidie van € 7.500 in de situatie van een jaarcontract of langer Het uniformeren van beleid ten aanzien van loonkostensubsidies draagt bij aan het verbeteren van de werkgeversdienstverlening in de regio. Een werkgever wil zo snel mogelijk een geschikte kandidaat vinden voor zijn vacature. -

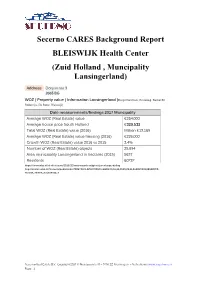

Secerno CARES Background Report BLEISWIJK Health Center (Zuid Holland , Muncipality Lansingerland)

Secerno CARES Background Report BLEISWIJK Health Center (Zuid Holland , Muncipality Lansingerland) Address Dorpstraat 3 2665 BG WOZ ( Property value ) Information Lansingerland (Bergschenhoek, Kruisweg, Berkel En Rodenrijs, De Rotte, Bleiswijk) Date measurements/findings 2017 Muncipality Average WOZ (Real Estate) value €264,000 Average house price South Holland €329.532 Total WOZ (Real Estate) value (2016) Million €13,169 Average WOZ (Real Estate) value housing (2016) €226,000 Growth WOZ (Real Estate) value 2016 vs 2015 3.4% Number of WOZ (Real Estate) objects 25,894 Area municipality Lansingerland in hectares (2015) 5637 Residents 60232 https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2016/32/woz-waarde-stijgt-na-jarenlange-daling http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLNL&PA=70262ned&D1=0,2,6,16,20,25,28,31,41&D2=418,685&D3=3- 7&HDR=T&STB=G1,G2&VW=T Secerno Real Estate B.V. Copyright 2017 © Nevelgaarde 40 – 3436 ZZ Nieuwegein – Netherlands www.secerno-re.nl Page : 1 Secerno Real Estate B.V. Copyright 2017 © Nevelgaarde 40 – 3436 ZZ Nieuwegein – Netherlands www.secerno-re.nl Page : 2 Population : 1 Jan 2017 Lansingerland %Population Population Bleiswijk 20% 11,919 Bergschenhoek 30% 18,075 Berkel en Rodenrijs 50% 30,048 100% 60,042 Secerno Real Estate B.V. Copyright 2017 © Nevelgaarde 40 – 3436 ZZ Nieuwegein – Netherlands www.secerno-re.nl Page : 3 Total Residents Lansingerland 0-5 5-10 15-20 15-20 20-25 25-30 30-35 35-40 40-45 45-50 50-55 55-60 60-65 65-70 70-75 75-80 80-85 85-90 90-95 90+ Total 2017 4077 4615 4426 3960 2708 2456 3317 4293 4727 -

1 Regional Population and Household Projections, 2011–2040

Regional population and household projections, 2011–2040: Marked regional differences Andries de Jong1 and Coen van Duin2 The regional population and household projections for 2011 to 2040 presents future developments in the population and number of households per municipality in the Netherlands. This article discusses five important future developments. First of all, the population of the Netherlands will continue to grow over the next 15 years. Growth will be particularly strong in the Randstad (meaning the urban conurbation of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht), but on the periphery of the country the population is expected to decline. Secondly, the number of households is also expected to continue to grow strongly throughout the Netherlands – only in north-east Groningen and Zeeuws-Vlaanderen will growth level off or even turn to decline. Thirdly, although the size of the potential labour force has increased continuously over the last few decades, it is expected to decline significantly in the near future. Decrease in the potential labour force, already a fact in many regions, will spread to almost all regions. Only in a strip that runs from The Hague Agglomeration, through Utrecht, Greater Amsterdam and Flevoland to north Overijssel will the potential labour force continue to grow over the coming 15 years. Fourthly, ageing of the population will accelerate in the coming decades as the post-war baby-boomers enter the over-65 age group. Although the number of people aged 65 and older will increase throughout the Netherlands, the increase will be stronger on the periphery of the country (where the strongest population decline is also expected) than in more urbanised areas, such as the Randstad. -

Besluitenlijst B&W Vergadering Wassenaar

Besluitenlijst B&W vergadering Wassenaar Datum 25-05-2021 Tijd 9:30 - 15:30 Locatie De Paauw, Raadzaal Voorzitter Dhr. L.A. de Lange Aanwezigen Burgemeester L. de Lange, wethouder C. Klaver-Bouman, wethouder I. Zweerts de Jong, wethouder H. Schokker, wethouder K. Wassenaar, wethouder Bloemendaal, gemeentesecretaris H. Oppatja, strategisch communicatieadviseur A. Oostermeijer (digitaal) en bestuursondersteuner S. Derr Toelichting 1 Opening 2 Openbare besluitenlijst 2021 Besluit 1. De openbare besluitenlijst van 18 mei vast te stellen. 3 Financiële tegemoetkoming voor de buurtcentra in Wassenaar Besluit 1. De buurtcentra in Wassenaar financieel met €5.500 per kwartaal, totaal € 11.000 (2 kwartalen), tegemoet te komen na inkomstenverlies door de Covid-19 (Corona) crisis, waardoor het mogelijk is om de huur te betalen. 2. Kennis te nemen van de daarvoor gestelde randvoorwaarden 3. Vooruitlopend op de besluitvorming van de voorjaarsnota direct € 11.000 beschikbaar te stellen voor het veiligstellen van het voortbestaan van de buurtcentra in Wassenaar. 4 Sociaal raadslid Besluit 1. Vooruitlopend op de besluitvorming van de voorjaarsnota € 20.625 beschikbaar te stellen voor het inzetten van de sociaal raadsvrouw, om de juridische kennis te borgen. 5 Jaarverslag leerplicht en Regionale Meld- en Coördinatiefunctie (RMC) schooljaar 2019-2020 Besluit 1. Het jaarverslag leerplicht en Regionale Meld- en Coördinatiefunctie (RMC) schooljaar 2019-2020 vast te stellen. 2. De raad met bijgevoegde raadsinformatiebrief over het jaarverslag leerplicht-RMC 2019 2020 te informeren 6 Beantwoording schriftelijke vragen DITdus! iz uitvoering participatiewet Besluit 1. De beantwoording van de schriftelijke vragen gesteld door DITdus! d.d. 30 april met betrekking tot Uitvoering Participatiewet art 36b, individuele studietoeslag vast te stellen 7 Samenwerkingsovereenkomst laaggeletterdheid / WEB 2021, Regio ZHC WS Besluit 1.