NAS-Trinity-14July05 -Fina Copyl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the PHYSICAL SCIENCES

UNITED STATES ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION RESEARCH CONTRACTS in the PHYSICAL SCIENCES he JULY 1, 1969 DIVISION OF RESEARCH INDEX Page Introduction .................................. ....................... ......... 2 List of Federally Funded Research and Development Centers ..................... 5 Summary of Off-Site Contracts ................................................. 6 Summary of New Proposals Received and Actions Taken ........................... 7 Summary of Contracts by State ................................................. 8 Contract Listing: High Energy Physics .................................................. 13 Medium Energy Physics ................................................ 15 Low Energy Physics ................................................... 16 Mathematics and Computer Research .................................... 20 Chemistry ......... .............................................. 22 Metallurgy and Materials ............................................. 32 Controlled Thermonuclear Research .................................... 41 1 INTRODUCT ION The Physical Research Program is chiefly concerned with basic research investigations undertaken to discover new scientific knowledge and also includes some applied research investigations relevant to certain aspects of the practical utilization of nuclear energy. Research is conducted in the fields of high, medium, and low energy physics, mathematics and computers, chemistry, metallurgy and materials, and controlled thermonuclear reactions. Approximately three-fourths -

Center for History of Physics Newsletter, Spring 2008

One Physics Ellipse, College Park, MD 20740-3843, CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS NIELS BOHR LIBRARY & ARCHIVES Tel. 301-209-3165 Vol. XL, Number 1 Spring 2008 AAS Working Group Acts to Preserve Astronomical Heritage By Stephen McCluskey mong the physical sciences, astronomy has a long tradition A of constructing centers of teaching and research–in a word, observatories. The heritage of these centers survives in their physical structures and instruments; in the scientific data recorded in their observing logs, photographic plates, and instrumental records of various kinds; and more commonly in the published and unpublished records of astronomers and of the observatories at which they worked. These records have continuing value for both historical and scientific research. In January 2007 the American Astronomical Society (AAS) formed a working group to develop and disseminate procedures, criteria, and priorities for identifying, designating, and preserving structures, instruments, and records so that they will continue to be available for astronomical and historical research, for the teaching of astronomy, and for outreach to the general public. The scope of this charge is quite broad, encompassing astronomical structures ranging from archaeoastronomical sites to modern observatories; papers of individual astronomers, observatories and professional journals; observing records; and astronomical instruments themselves. Reflecting this wide scope, the members of the working group include historians of astronomy, practicing astronomers and observatory directors, and specialists Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Santa encounters tight security during in astronomical instruments, archives, and archaeology. a wartime visit to Oak Ridge. Many more images recently donated by the Digital Photo Archive, Department of Energy appear on page 13 and The first item on the working group’s agenda was to determine through out this newsletter. -

Trinity Transcript

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES Committee on International Security and Arms Control 60th Anniversary of Trinity: First Manmade Nuclear Explosion, July 16, 1945 PUBLIC SYMPOSIUM July 14, 2005 National Academy of Sciences Auditorium 2100 C Street, NW Washington, DC Proceedings By: CASET Associates, Ltd. 10201 Lee Highway, Suite 180 Fairfax, VA 22030 (703) 352-0091 CONTENTS PAGE Introductory Remarks Welcome: Ralph Cicerone, President, The National Academies (NAS) 1 Introduction: Raymond Jeanloz, Chair, Committee on International Security and Arms Control (CISAC) 3 Roundtable Discussion by Trinity Veterans Introduction: Wolfgang Panofsky, Chair 5 Individual Statements by Trinity Veterans: Harold Agnew 10 Hugh Bradner 13 Robert Christy 16 Val Fitch 20 Don Hornig 24 Lawrence Johnston 29 Arnold Kramish 31 Louis Rosen 35 Maurice Shapiro 38 Rubby Sherr 41 Harold Agnew (continued) 43 1 PROCEEDINGS 8:45 AM DR. JEANLOZ: My name is Raymond Jeanloz, and I am the Chair of the Committee on International Security and Arms Control that organized this morning’s symposium, recognizing the 60th anniversary of Trinity, the first manmade nuclear explosion. I will be the moderator for today’s event, and primarily will try to stay out of the way because we have many truly distinguished and notable speakers. In order to allow them the maximum amount of time, I will only give brief introductions and ask that you please turn to the biographical information that has been provided to you. To start with, it is my special honor to introduce Ralph Cicerone, the President of the National Academy of Sciences, who will open our meeting with introductory remarks. He is a distinguished researcher and scientific leader, recently serving as Chancellor of the University of California at Irvine, and his work in the area of climate change and pollution has had an important impact on policy. -

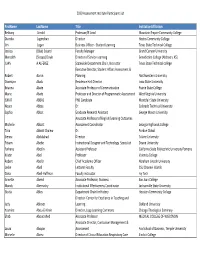

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List Firstname Lastname Title

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List FirstName LastName Title InstitutionAffiliation Bethany Arnold Professor/IE Lead Mountain Empire Community College Diandra Jugmohan Director Hostos Community College Jim Logan Business Officer ‐ Student Learning Texas State Technical College Jessica (Blair) Soland Faculty Manager Grand Canyon University Meredith (Stoops) Doyle Director of Service‐Learning Benedictine College (Atchison, KS) JUAN A ALFEREZ Statewide Department Chair, Instructor Texas State Technical college Executive Director, Student Affairs Assessment & Robert Aaron Planning Northwestern University Osomiyor Abalu Residence Hall Director Iowa State University Brianna Abate Associate Professor of Communication Prairie State College Marie Abate Professor and Director of Programmatic Assessment West Virginia University ISMAT ABBAS PhD Candidate Montclair State University Noura Abbas Dr. Colorado Technical University Sophia Abbot Graduate Research Assistant George Mason University Associate Professor of English/Learning Outcomes Michelle Abbott Assessment Coordinator Georgia Highlands College Talia Abbott Chalew Dr. Purdue Global Sienna Abdulahad Director Tulane University Fitsum Abebe Instructional Designer and Technology Specialist Doane University Farhana Abedin Assistant Professor California State Polytechnic University Pomona Kristin Abel Professor Valencia College Robert Abel Jr Chief Academic Officer Abraham Lincoln University Leslie Abell Lecturer Faculty CSU Channel Islands Dana Abell‐Huffman Faculty instructor Ivy Tech Annette -

Robert Dicke and the Naissance of Experimental Gravity Physics

Eur. Phys. J. H 42, 177–259 (2017) DOI: 10.1140/epjh/e2016-70034-0 THE EUROPEAN PHYSICAL JOURNAL H RobertDickeandthenaissance of experimental gravity physics, 1957–1967 Phillip James Edwin Peeblesa Joseph Henry Laboratories, Princeton University, Princeton NJ, USA Received 27 May 2016 / Received in final form 22 June 2016 Published online 6 October 2016 c The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract. The experimental study of gravity became much more active in the late 1950s, a change pronounced enough be termed the birth, or naissance, of experimental gravity physics. I present a review of devel- opments in this subject since 1915, through the broad range of new approaches that commenced in the late 1950s, and up to the transition of experimental gravity physics to what might be termed a normal and accepted part of physical science in the late 1960s. This review shows the importance of advances in technology, here as in all branches of nat- ural science. The role of contingency is illustrated by Robert Dicke’s decision in the mid-1950s to change directions in mid-career, to lead a research group dedicated to the experimental study of gravity. The re- view also shows the power of nonempirical evidence. Some in the 1950s felt that general relativity theory is so logically sound as to be scarcely worth the testing. But Dicke and others argued that a poorly tested theory is only that, and that other nonempirical arguments, based on Mach’s Principle and Dirac’s Large Numbers hypothesis, suggested it would be worth looking for a better theory of gravity. -

Nuclear Weapons FAQ (NWFAQ) Organization Back to Main Index

Nuclear Weapons FAQ (NWFAQ) Organization Back to Main Index This is a complete listing of the decimally numbered headings of the Nuclear Weapons Frequently Asked Questions, which provides a comprehensive view of the organization and contents of the document. Index 1.0 Types of Nuclear Weapons 1.1 Terminology 1.2 U.S. Nuclear Test Names 1.3 Units of Measurement 1.4 Pure Fission Weapons 1.5 Combined Fission/Fusion Weapons 1.5.1 Boosted Fission Weapons 1.5.2 Staged Radiation Implosion Weapons 1.5.3 The Alarm Clock/Sloika (Layer Cake) Design 1.5.4 Neutron Bombs 1.6 Cobalt Bombs 2.0 Introduction to Nuclear Weapon Physics and Design 2.1 Fission Weapon Physics 2.1.1 The Nature Of The Fission Process 2.1.2 Criticality 2.1.3 Time Scale of the Fission Reaction 2.1.4 Basic Principles of Fission Weapon Design 2.1.4.1 Assembly Techniques - Achieving Supercriticality 2.1.4.1.1 Implosion Assembly 2.1.4.1.2 Gun Assembly 2.1.4.2 Initiating Fission 2.1.4.3 Preventing Disassembly and Increasing Efficiency 2.2 Fusion Weapon Physics 2.2.1 Candidate Fusion Reactions 2.2.2 Basic Principles of Fusion Weapon Design 2.2.2.1 Designs Using the Deuterium+Tritium Reaction 2.2.2.2 Designs Using Other Fuels 3.0 Matter, Energy, and Radiation Hydrodynamics 3.1 Thermodynamics and the Properties of Gases 3.1.1 Kinetic Theory of Gases 3.1.2 Heat, Entropy, and Adiabatic Compression 3.1.3 Thermodynamic Equilibrium and Equipartition 3.1.4 Relaxation 3.1.5 The Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution Law 3.1.6 Specific Heats and the Thermodynamic Exponent 3.1.7 Properties of Blackbody -

History Newsletter CENTER for HISTORY of PHYSICS&NIELS BOHR LIBRARY & ARCHIVES Vol

History Newsletter CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS&NIELS BOHR LIBRARY & ARCHIVES Vol. 45, No. 2 • Winter 2013–2014 1,000+ Oral History Interviews Now Online Since June 2007, the Niels Bohr Library societies. Some of the interviews were Through this hard work, we have been & Archives (NBL&A) has been working conducted by staff of the Center for able to receive updated permissions to place its widely used oral history History of Physics (CHP) and many were and often hear from families that did interview collection online for its acquired from individual scholars who not know an interview existed and are researchers to easily access. With the were often helped by our Grant-in-Aid pleased to know that their relative’s work help of two National Endowment for the program. These interviews help tell will be remembered and available to Humanities (NEH) grants, we are proud the personal stories of these famous anyone interested. to announce that we have now placed over two- With the completion of thirds of our collection the grants, we have just online (http://www.aip.org/ over 1,025 of our over history/ohilist/transcripts. 1,500 transcripts online. html ). These transcripts include abstracts of the interview, The oral histories at photographs from ESVA NBL&A are one of our when available, and links most used collections, to the interview’s catalog second only to the record in our International photographs in the Emilio Catalog of Sources (ICOS). Segrè Visual Archives We have short audio clips (ESVA). They cover selected by our post- topics such as quantum doctoral historian of 75 physics, nuclear physics, physicists in a range of astronomy, cosmology, solid state physicists and allow the reader insight topics showing some of the interesting physics, lasers, geophysics, industrial into their lives, works, and personalities. -

University of Minnesota

THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Announces Its );tareft eommcllecmcllt 1963 NORTHROP MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM SATURDAY EVENING, MARCH 23 AT EIGHT THIRTY O'CLOCK Universitv of Minnesota THE BOARD OF REGENTS* Dr. O. Meredith Wilson, President Mr. Laurence R. Lunden, Secretary Mr. Clinton T. Johnson, Treasurer Mr. Sterling B. Garrison, Assistant Secretary The Honorable Charles W. Mayo, M.D., Rochester First Vice President and Chairman The Honorable Marjorie J. Howard (Mrs. C. Edward), Excelsior Second Vice President The Honorable Daniel C. Gainey, Owatonna The Honorable Richard L. Griggs, Duluth The Honorable Bjarne E. Grottum, Jackson The Honorable Robert E. Hess, White Bear Lake The Honorable Fred J. Hughes, St. Cloud The Honorable A. I. Johnson, Benson The Honorable Lester A. Malkerson, Minneapolis The Honorable A. J. Olson, Renville The Honorable Otto A. Silha, Minneapolis The Honorable Herman F. Skyberg, Fisher *As of March 12, 1963. SMOKING AND USE OF CAMERAS AND RECORDERS-It is requested, by action of the Board of Regents, that in Northrop Memorial Auditorium smoking be confined to the outer lobby on the main floor, to the gallery lobbies, and to the lounge rooms. The use of cameras or tape recorders in the auditorium by members of the audio ence is prohibited. ?:ltis /s V(Jllr Univcrsitg CHARTERED in February, 1851, by the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Minnesota, the University of Minnesota this year celebrated its one hundred and twelfth birthday. As one of the great Land-Grant universities in the nation, the University of Minnesota is dedicated to training the young people of today to become the leaders of tomorrow. -

Robert Dicke and the Naissance of Experimental Gravity Physics, 1957-1967

EPJ manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Robert Dicke and the naissance of experimental gravity physics, 1957-1967 P. J. E. Peeblesa Joseph Henry Laboratories Princeton University, Princeton NJ USA Abstract. The experimental study of gravity became much more active in the late 1950s, a change pronounced enough be termed the birth, or naissance, of experimental gravity physics. I present a review of devel- opments in this subject since 1915, through the broad range of new approaches that commenced in the late 1950s, and up to the transition of experimental gravity physics to what might be termed a normal and accepted part of physical science in the late 1960s. This review shows the importance of advances in technology, here as in all branches of nat- ural science. The role of contingency is illustrated by Robert Dicke's decision in the mid-1950s to change directions in mid-career, to lead a research group dedicated to the experimental study of gravity. The re- view also shows the power of nonempirical evidence. Some in the 1950s felt that general relativity theory is so logically sound as to be scarcely worth the testing. But Dicke and others argued that a poorly tested theory is only that, and that other nonempirical arguments, based on Mach's Principle and Dirac's Large Numbers hypothesis, suggested it would be worth looking for a better theory of gravity. I conclude by offering lessons from this history, some peculiar to the study of grav- ity physics during the naissance, some of more general relevance. The central lesson, which is familiar but not always well advertised, is that physical theories can be empirically established, sometimes with sur- prising results. -

![[New] Name? CENTER](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1229/new-name-center-6431229.webp)

[New] Name? CENTER

CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS NEWSLETTER Vol. XXXIX, Number 1 Spring 2007 One Physics Ellipse, College Park, MD 20740-3843, Tel. 301-209-3165 Publication of the Collected Works of Niels Bohr Completed by Finn Aaserud ith the publication of the twelfth and final volume of the W Niels Bohr Collected Works, one of the very greatest physicists of the twentieth century is brought before the public in one of the premier works of scholarship in modern history of science. Planning for the publication of the Collected Works began soon after Bohr’s death in 1962. The driving force behind the project was Bohr’s close collaborator, the Belgian physicist and historian of science Léon Rosenfeld, who was the first General Editor of the series. The first volume, covering the early years up to 1911, was published in 1972 with Jens Rud Nielsen (1894–1979) as editor. However, this was the only volume that Rosenfeld would see, for he died in 1974. The project, originally conceived as a ten-year effort, was not completed until well into the next century. After an interim period with Rud Nielsen doing the brunt of the work, Erik Rüdinger was named General Editor in 1977. Mary Calvert using the 12-inch refractor at Yerkes Observatory, Rüdinger had served as Bohr’s scientific assistant for a brief February 23, 1926. She was Edward E. Barnard’s niece, and after period near the end of Bohr’s life. In Volume 5 (published his death, co-editor of his book A Photographic Atlas of Selected 1985), the first under Rüdinger’s control, Rüdinger laid out the Regions of the Milky Way published in 1927 by the Carnegie general editorial policy and practice that have been followed Institution of Washington. -

History Newsletter

HISTORY NEWSLETTER One Physics Ellipse CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS NEWSLETTER Vol. XXXVII, Number 1 Spring 2005 College Park, MD 20740-3843 AIP Tel. 301-209-3165 National Park Service to Study Manhattan Project Sites by Cynthia C. Kelly, President, Atomic Heritage Foundation he National Park Service has been authorized to take the T first step in creating one or more National Park sites for the Manhattan Project, the top-secret effort to make an atomic bomb in World War II. With the support of the New Mexico, Tennessee and Washington delegations, the 108th Congress passed the “Manhattan Project National Historic Park Study Act” (S. 1687) that was signed by the President on October 18, 2004. The new legislation directs the Secretary of the Interior “to con- duct a study on the preservation and interpretation of the his- toric sites of the Manhattan Project for potential inclusion in the National Park System.” The law sets a deadline of two years after the date on which funds are made available to carry out the study. The expectation is that funds will be available through the Department of Energy for this purpose in FY 2005. The study will address the national significance, suitability, and feasibility of designating the Manhattan Project sites at Los Alamos, New Mexico; Hanford, Washington; and Oak Ridge, Tennessee; and possibly other sites associated with the Man- hattan Project, as units of the National Park System. The study will consider both Federal and non-Federal properties associ- Pouring optical glass in Germany at the turn of the 20th century, an ated with the Manhattan Project. -

May 23-26, 2014 • Hyatt Regency Santa Clara Contents Chairman’S Welcome to Baycon 2014

May 23-26, 2014 • Hyatt Regency Santa Clara Contents Chairman’s Welcome to BayCon 2014 ..........................................3 BayCon 2014 Variety Show ......................................................... 21 David Weber • Writer Guest of Honor .........................................5 BayCon DIY Room ...................................................................... 22 Ursula Vernon • Artist Guest of Honor ........................................6 Gofers • Convention Volunteers .................................................24 Sally Woerhle • Fan Guest of Honor .............................................8 Art Show ........................................................................................ 25 Tom Merritt • Toastmaster ..........................................................10 BayCon Marketplace • Dealers Room ....................................... 26 BayCon 2014 Charity ...................................................................13 Birds of a Feather ..........................................................................26 BayCon Staff ..................................................................................14 Charity Events ...............................................................................27 BayCon Harassment Policy .........................................................15 Play Pod ......................................................................................... 27 Hotel Information ........................................................................ 17 Teen