The Struggle for the Seleucid Succession, 94-92 BC : a New Tetradrachm of Antiochus XI and Philip I of Antioch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lara O'sullivan, Fighting with the Gods

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME TWENTY-EIGHT: 2014 NUMBERS 3-4 Edited by: Edward Anson ò David Hollander ò Timothy Howe Joseph Roisman ò John Vanderspoel ò Pat Wheatley ò Sabine Müller ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 28 (2014) Numbers 3-4 Edited by: Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume twenty-eight Numbers 3-4 82 Lara O’Sullivan, Fighting with the Gods: Divine Narratives and the Siege of Rhodes 99 Michael Champion, The Siege of Rhodes and the Ethics of War 112 Alexander K. Nefedkin, Once More on the Origin of Scythed Chariot 119 David Lunt, The Thrill of Victory and the Avoidance of Defeat: Alexander as a Sponsor of Athletic Contests NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Leuven), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel and Pat Wheatley. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics Title The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xh6g8nn Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics, 2(1) ISSN 2373-7115 Author Gavryushkina, Marina Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gavryushkina 1 The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013 Abstract: Hellenistic coinage is a popular topic in art historical research as it is an invaluable resource of information about the political relationship between Greek rulers and their subjects. However, most scholars have focused on the wealthier and more famous dynasties of the Ptolemies and the Seleucids. Thus, there have been considerably fewer studies done on the artistic styles of the coins of the smaller outlying Hellenistic kingdoms. This paper analyzes the numismatic portraiture of the kings of Pontus, a peripheral kingdom located in northern Anatolia along the shores of the Black Sea. In order to evaluate the degree of similarity or difference in the Pontic kings’ modes of representation in relation to the traditional royal Hellenistic style, their coinage is compared to the numismatic depictions of Alexander the Great of Macedon. A careful art historical analysis reveals that Pontic portrait styles correlate with the individual political motivations and historical circumstances of each king. Pontic rulers actively choose to diverge from or emulate the royal Hellenistic portrait style with the intention of either gaining support from their Anatolian and Persian subjects or being accepted as legitimate Greek sovereigns within the context of international politics. -

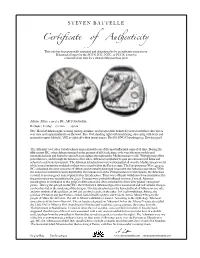

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

The Coinage of Akragas C

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Numismatica Upsaliensia 6:1 STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA 6:1 The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC Text and Plates ULLA WESTERMARK I STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA Editors: Harald Nilsson, Hendrik Mäkeler and Ragnar Hedlund 1. Uppsala University Coin Cabinet. Anglo-Saxon and later British Coins. By Elsa Lindberger. 2006. 2. Münzkabinett der Universität Uppsala. Deutsche Münzen der Wikingerzeit sowie des hohen und späten Mittelalters. By Peter Berghaus and Hendrik Mäkeler. 2006. 3. Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. Svenska vikingatida och medeltida mynt präglade på fastlandet. By Jonas Rundberg and Kjell Holmberg. 2008. 4. Opus mixtum. Uppsatser kring Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. 2009. 5. ”…achieved nothing worthy of memory”. Coinage and authority in the Roman empire c. AD 260–295. By Ragnar Hedlund. 2008. 6:1–2. The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC. By Ulla Westermark. 2018 7. Musik på medaljer, mynt och jetonger i Nils Uno Fornanders samling. By Eva Wiséhn. 2015. 8. Erik Wallers samling av medicinhistoriska medaljer. By Harald Nilsson. 2013. © Ulla Westermark, 2018 Database right Uppsala University ISSN 1652-7232 ISBN 978-91-513-0269-0 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876 (http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876) Typeset in Times New Roman by Elin Klingstedt and Magnus Wijk, Uppsala Printed in Sweden on acid-free paper by DanagårdLiTHO AB, Ödeshög 2018 Distributor: Uppsala University Library, Box 510, SE-751 20 Uppsala www.uu.se, [email protected] The publication of this volume has been assisted by generous grants from Uppsala University, Uppsala Sven Svenssons stiftelse för numismatik, Stockholm Gunnar Ekströms stiftelse för numismatisk forskning, Stockholm Faith and Fred Sandstrom, Haverford, PA, USA CONTENTS FOREWORDS ......................................................................................... -

Art and Royalty in Sparta of the 3Rd Century B.C

HESPERIA 75 (2006) ART AND ROYALTY Pages 203?217 IN SPARTA OF THE 3RD CENTURY B.C. ABSTRACT a The aim of this paper is to demonstrate that revival of the arts in Sparta b.c. was during the 3rd century owed mainly to royal patronage, and that it was inspired by Alexander s successors, the Seleukids and the Ptolemies in particular. The tumultuous transition from the traditional Spartan dyarchy to a and to its dominance Hellenistic-style monarchy, Sparta's attempts regain in the P?loponn?se (lost since the battle of Leuktra in 371 b.c.), are reflected in the of the hero Herakles as a role model promotion pan-Peloponnesian at for the single king the expense of the Dioskouroi, who symbolized dual a kingship and had limited, regional appeal. INTRODUCTION was Spartan influence in the P?loponn?se dramatically reduced after the battle of Leuktra in 371 b.c.1 The history of Sparta in the 3rd century b.c. to ismarked by intermittent efforts reassert Lakedaimonian hegemony.2 A as a means to tendency toward absolutism that end intensified the latent power struggle between the Agiad and Eurypontid royal houses, leading to the virtual abolition of the traditional dyarchy in the reign of the Agiad Kleomenes III (ca. 235-222 b.c.), who appointed his brother Eukleides 1. For the battle of Leuktra and its am to and Ellen Millen 2005.1 grateful Graham Shipley Paul Cartledge and see me to am consequences, Cartledge 2002, and Ellen Millender for inviting der for historical advice. I also 251-259. -

Cult Statue of a Goddess

On July 31, 2007, the Italian Ministry of Culture and the Getty Trust reached an agreement to return forty objects from the Museum’s antiq uities collection to Italy. Among these is the Cult Statue of a Goddess. This agreement was formally signed in Rome on September 25, 2007. Under the terms of the agreement, the statue will remain on view at the Getty Villa until the end of 2010. Cult Statue of a Goddess Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at The Getty Villa May 9, 2007 i © 2007 The J. Paul Getty Trust Published on www.getty.edu in 2007 by The J. Paul Getty Museum Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 900491682 www.getty.edu Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Benedicte Gilman, Editor Diane Franco, Typography ISBN 9780892369287 This publication may be downloaded and printed in its entirety. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for noncommercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors. For any other uses, please refer to the J. Paul Getty Trust’s Terms of Use. ii Cult Statue of a Goddess Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at the Getty Villa, May 9, 2007 Schedule of Proceedings iii Introduction, Michael Brand 1 Acrolithic and Pseudoacrolithic Sculpture in Archaic and Classical Greece and the Provenance of the Getty Goddess Clemente Marconi 4 Observations on the Cult Statue Malcolm Bell, III 14 Petrographic and Micropalaeontological Data in Support of a Sicilian Origin for the Statue of Aphrodite Rosario Alaimo, Renato Giarrusso, Giuseppe Montana, and Patrick Quinn 23 Soil Residues Survey for the Getty Acrolithic Cult Statue of a Goddess John Twilley 29 Preliminary Pollen Analysis of a Soil Associated with the Cult Statue of a Goddess Pamela I. -

Eustathius of Antioch in Modern Research

VOX PATRUM 33 (2013) t. 59 Sophie CARTWRIGHT* EUSTATHIUS OF ANTIOCH IN MODERN RESEARCH Eustathius of Beroea/Antioch remains an elusive figure, though there is a growing recognition of his importance to the history of Christian theology, and particularly the early part of the so-called ‘Arian’ controversies. The re- cent publication of a fresh edition of his writings, including a newly-attributed epitome entitled Contra Ariomanitas et de anima, demands fresh considera- tion of Eustathius1. However, the previous scholarship on Eustathius is too little known for such an enterprise to take place. This article has two related tasks: firstly, to provide a comprehensive survey of the treatment of Eustathius in modern scholarship2; secondly, to assess the current state of research on Eustathius. With the exception of Eustathian exegesis, the work on Eustathi- us’s theology between the early twentieth century and the publication of the new epitome has been extremely limited. The scholarship that has followed this publication has yet to situate its observations within more recent histo- riographical developments in patristic theology and philosophy, but points to- wards several contours that must be fundamental to this endeavour. Firstly, Eustathius’s relationship to Origen must be closely considered in connection with his long-noted dependence on Irenaeus and other theologians from Asia Minor. Secondly, Aristotle, or ‘Aristotelianism’, suggests itself as an impor- tant resource for Eustathius – this resource must now be understood in light of recent discussions on the role of Aristotle’s thought, and its relation to Plato- nism, in antiquity. This can, in turn, help to elucidate the history of Irenaeus’s legacy, Origenism, and readings of Aristotle in the fourth century. -

Greetings and Thanksgiving the Salutation

Thessalonians 1 & 2 1 Thessalonian 1: Greetings and Thanksgiving The Salutation The salutation names three authors of the letter, Paul, Silvanus, also known by his nickname Silas, and Timothy. Both of Paul’s fellow workers played important roles in the development of his missionary activity. According to Acts 15:22, Silas was part of the delegation sent to Antioch to announce the results of the “apostolic council” in Jerusalem. Paul chose him as a companion in his missionary activity in Syria and Cilicia, his “first missionary journey” (Acts 15:40). It was during that journey, in Derbe and Lystra, where Paul encountered Timothy, son of a Jewish mother and Greek father (Acts 16:1), whom he recruited to his missionary team. Silas continued with Paul and was with him in prison in Philippi (Acts 16:19–40), and he was with Paul when the apostle initially worked in Thessalonica (Acts 17:4-9) and Beroea (Acts 17:10). Timothy apparently was part of the team as well, since he remained with Silas in Beroea when Paul was sent off (Acts 17:14). Silas and Timothy reunited with Paul in Athens (Acts 18:5), which was probably the location from which Paul sent Timothy on the mission to Thessalonica, a mission to which he refers later in 1 Thess 3:2. If the account in Acts is correct, Silas accompanied Timothy on the trip; and the two rejoined Paul in Corinth (Acts 18:5), providing the occasion for writing the letter. The presence of Silas and Timothy with Paul in Corinth when he first preached there is confirmed by Paul’s reminiscence of the start of his mission there in 2 Corinthians 1:19. -

Background for the Bible Passage Session !: God in Culture

BACKGROUND FOR THE BIBLE PASSAGE SESSION !: GOD IN CULTURE Life Question: How can I use culture to express my who, no doubt, lifted him up mightily in prayer would be an faith? encouragement to him as he faced an entirely new experience Biblical Truth: We can start where people are in their in Athens. cultures to explain to them the message Certainly Paul had heard much about Athens previously, but of Christ. we can only imagine that he was ill-prepared for what he found Focal Passage: Acts 17:16-34 as he entered the city through one of its massive gates. The wall surrounding Athens had a circumference of 5 to 6 miles. Most likely Paul was awed by architecture that greeted him, with the Ben Feldman moved to Central City High School when he was grandeur of this center of Greek culture. If Paul had entered the a junior. His father, a prominent neurosurgeon, had joined the city through one of the northeast gates, he probably saw first medical faculty at Central City’s large teaching hospital. The the Hephaesteum, a beautiful Doric temple built between 449- family had moved from upstate New York to the deep South, 444 B.C. and dedicated to the god Hephaestus and the goddess and more specifically to the Bible Belt. Ben’s family came from Athena. Across from the Hephaesteum was the Stoa of Attalus, an entirely different culture in which “religion” was little more a two-storied, colonnaded building which was given to Athens than a traditional heritage. Ben was a brilliant student who around A.D. -

Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian

Epidamnus S tr Byzantium ym THRACE on R Amphipolis A . NI PROPONTIS O Eion ED Thasos Cyzicus C Stagira Aegospotami A Acanthus CHALCIDICE M Lampsacus Dascylium Potidaea Cynossema Scione Troy AEOLIS LY Corcyra SA ES Ambracia H Lesbos T AEGEAN MYSIA AE SEA Anactorium TO Mytilene Sollium L Euboea Arginusae Islands L ACAR- IA YD Delphi IA NANIA Delium Sardes PHOCISThebes Chios Naupactus Gulf Oropus Erythrae of Corinth IONIA Plataea Decelea Chios Notium E ACHAEA Megara L A Athens I R Samos Ephesus Zacynthus S C Corinth Piraeus ATTICA A Argos Icaria Olympia D Laureum I Epidaurus Miletus A Aegina Messene Delos MESSENIA LACONIA Halicarnassus Pylos Sparta Melos Cythera Rhodes 100 miles 160 km Crete Map 1 Greece. xvii W h i t 50 km e D r i n I R. D rin L P A E O L N IA Y Bylazora R . B S la t R r c R y k A . m D I A ) o r x i N a ius n I n n ( Epidamnus O r V e ar G C d ( a A r A n ) L o ig Lychnidus E r E P .E . R o (Ochrid) R rd a ic s u Heraclea u s r ) ( S o s D Lyncestis d u U e c ev i oll) Pella h l Antipatria C c l Edessa a Amphipolis S YN E TI L . G (Berat) E ( AR R DASS Celetrum Mieza Koritsa E O O R Beroea R.Ao R D Aegae (Vergina) us E A S E on Methone T m I A c Olynthus S lia Pydna a A Thermaic . -

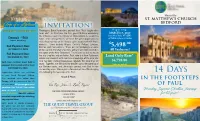

14 Days at Your Local Passport Office

Hosted By: JOIN US YOUR ST. MATTHEW’S CHURCH for a BEDFORD Trip of a Lifetime INVITATION! Departing: IMPORTANT INFORMATION Theologian, Ernst Kasemann, posited that: “Paul taught what Jesus did.” St. Paul was the first great Christian missionary. MARCH 15, 2020 from New York, NY (JFK) $ His influence upon the history of Christendom is second to Deposit - 500 none. This coming March, we have the great opportunity to on Turkish Airlines or similar (upon booking) visit a large number of the historic sights associated with Paul’s ministry. Stops include Athens, Corinth, Philippi, Ephesus, $ .00 2nd Payment Due: Patmos, and many others. These are the birthplaces of some 5,498 OCTOBER 17, 2019 of the earliest Christian churches, and are well documented in All Inclusive! the pages of the New Testament. The trip will be led by me, as Full Payment Due: the trip chaplain, and my father, Paul, who is a New Testament Land Only Rate* DECEMBER 31, 2019 scholar and classicist with extensive knowledge of the area, and who has been visiting these places regularly for more than 40 $4,798.00 Each tour member must hold a years. Together, we will certainly deepen our understanding of passport that is valid until at least *Airfare not included our Christian roots, and, ultimately, connect with God in new OCTOBER 15, 2020. and exciting ways. Please join us for what will be a life-changing Application forms are available trip, following the footsteps of St. Paul. 14 Days at your local Passport Office. Grace & Peace, Any required visas other than IN THE FOOTSTEPS Turkey, will be processed for US citizens only.