Athenian Tetradrachm Coinage of the First Half of the Fourth Century Bc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics Title The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xh6g8nn Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics, 2(1) ISSN 2373-7115 Author Gavryushkina, Marina Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gavryushkina 1 The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013 Abstract: Hellenistic coinage is a popular topic in art historical research as it is an invaluable resource of information about the political relationship between Greek rulers and their subjects. However, most scholars have focused on the wealthier and more famous dynasties of the Ptolemies and the Seleucids. Thus, there have been considerably fewer studies done on the artistic styles of the coins of the smaller outlying Hellenistic kingdoms. This paper analyzes the numismatic portraiture of the kings of Pontus, a peripheral kingdom located in northern Anatolia along the shores of the Black Sea. In order to evaluate the degree of similarity or difference in the Pontic kings’ modes of representation in relation to the traditional royal Hellenistic style, their coinage is compared to the numismatic depictions of Alexander the Great of Macedon. A careful art historical analysis reveals that Pontic portrait styles correlate with the individual political motivations and historical circumstances of each king. Pontic rulers actively choose to diverge from or emulate the royal Hellenistic portrait style with the intention of either gaining support from their Anatolian and Persian subjects or being accepted as legitimate Greek sovereigns within the context of international politics. -

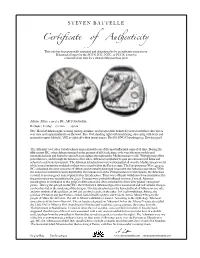

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

The Coinage of Akragas C

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Numismatica Upsaliensia 6:1 STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA 6:1 The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC Text and Plates ULLA WESTERMARK I STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA Editors: Harald Nilsson, Hendrik Mäkeler and Ragnar Hedlund 1. Uppsala University Coin Cabinet. Anglo-Saxon and later British Coins. By Elsa Lindberger. 2006. 2. Münzkabinett der Universität Uppsala. Deutsche Münzen der Wikingerzeit sowie des hohen und späten Mittelalters. By Peter Berghaus and Hendrik Mäkeler. 2006. 3. Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. Svenska vikingatida och medeltida mynt präglade på fastlandet. By Jonas Rundberg and Kjell Holmberg. 2008. 4. Opus mixtum. Uppsatser kring Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. 2009. 5. ”…achieved nothing worthy of memory”. Coinage and authority in the Roman empire c. AD 260–295. By Ragnar Hedlund. 2008. 6:1–2. The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC. By Ulla Westermark. 2018 7. Musik på medaljer, mynt och jetonger i Nils Uno Fornanders samling. By Eva Wiséhn. 2015. 8. Erik Wallers samling av medicinhistoriska medaljer. By Harald Nilsson. 2013. © Ulla Westermark, 2018 Database right Uppsala University ISSN 1652-7232 ISBN 978-91-513-0269-0 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876 (http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876) Typeset in Times New Roman by Elin Klingstedt and Magnus Wijk, Uppsala Printed in Sweden on acid-free paper by DanagårdLiTHO AB, Ödeshög 2018 Distributor: Uppsala University Library, Box 510, SE-751 20 Uppsala www.uu.se, [email protected] The publication of this volume has been assisted by generous grants from Uppsala University, Uppsala Sven Svenssons stiftelse för numismatik, Stockholm Gunnar Ekströms stiftelse för numismatisk forskning, Stockholm Faith and Fred Sandstrom, Haverford, PA, USA CONTENTS FOREWORDS ......................................................................................... -

Art and Royalty in Sparta of the 3Rd Century B.C

HESPERIA 75 (2006) ART AND ROYALTY Pages 203?217 IN SPARTA OF THE 3RD CENTURY B.C. ABSTRACT a The aim of this paper is to demonstrate that revival of the arts in Sparta b.c. was during the 3rd century owed mainly to royal patronage, and that it was inspired by Alexander s successors, the Seleukids and the Ptolemies in particular. The tumultuous transition from the traditional Spartan dyarchy to a and to its dominance Hellenistic-style monarchy, Sparta's attempts regain in the P?loponn?se (lost since the battle of Leuktra in 371 b.c.), are reflected in the of the hero Herakles as a role model promotion pan-Peloponnesian at for the single king the expense of the Dioskouroi, who symbolized dual a kingship and had limited, regional appeal. INTRODUCTION was Spartan influence in the P?loponn?se dramatically reduced after the battle of Leuktra in 371 b.c.1 The history of Sparta in the 3rd century b.c. to ismarked by intermittent efforts reassert Lakedaimonian hegemony.2 A as a means to tendency toward absolutism that end intensified the latent power struggle between the Agiad and Eurypontid royal houses, leading to the virtual abolition of the traditional dyarchy in the reign of the Agiad Kleomenes III (ca. 235-222 b.c.), who appointed his brother Eukleides 1. For the battle of Leuktra and its am to and Ellen Millen 2005.1 grateful Graham Shipley Paul Cartledge and see me to am consequences, Cartledge 2002, and Ellen Millender for inviting der for historical advice. I also 251-259. -

Cult Statue of a Goddess

On July 31, 2007, the Italian Ministry of Culture and the Getty Trust reached an agreement to return forty objects from the Museum’s antiq uities collection to Italy. Among these is the Cult Statue of a Goddess. This agreement was formally signed in Rome on September 25, 2007. Under the terms of the agreement, the statue will remain on view at the Getty Villa until the end of 2010. Cult Statue of a Goddess Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at The Getty Villa May 9, 2007 i © 2007 The J. Paul Getty Trust Published on www.getty.edu in 2007 by The J. Paul Getty Museum Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 900491682 www.getty.edu Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Benedicte Gilman, Editor Diane Franco, Typography ISBN 9780892369287 This publication may be downloaded and printed in its entirety. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for noncommercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors. For any other uses, please refer to the J. Paul Getty Trust’s Terms of Use. ii Cult Statue of a Goddess Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at the Getty Villa, May 9, 2007 Schedule of Proceedings iii Introduction, Michael Brand 1 Acrolithic and Pseudoacrolithic Sculpture in Archaic and Classical Greece and the Provenance of the Getty Goddess Clemente Marconi 4 Observations on the Cult Statue Malcolm Bell, III 14 Petrographic and Micropalaeontological Data in Support of a Sicilian Origin for the Statue of Aphrodite Rosario Alaimo, Renato Giarrusso, Giuseppe Montana, and Patrick Quinn 23 Soil Residues Survey for the Getty Acrolithic Cult Statue of a Goddess John Twilley 29 Preliminary Pollen Analysis of a Soil Associated with the Cult Statue of a Goddess Pamela I. -

Mercenaries, Poleis, and Empires in the Fourth Century Bce

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts ALL THE KING’S GREEKS: MERCENARIES, POLEIS, AND EMPIRES IN THE FOURTH CENTURY BCE A Dissertation in History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies by Jeffrey Rop © 2013 Jeffrey Rop Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 ii The dissertation of Jeffrey Rop was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark Munn Professor of Ancient Greek History and Greek Archaeology, Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Gary N. Knoppers Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, Religious Studies, and Jewish Studies Garrett G. Fagan Professor of Ancient History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Kenneth Hirth Professor of Anthropology Carol Reardon George Winfree Professor of American History David Atwill Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Graduate Program Director for the Department of History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Greek mercenary service in the Near East from 401- 330 BCE. Traditionally, the employment of Greek soldiers by the Persian Achaemenid Empire and the Kingdom of Egypt during this period has been understood to indicate the military weakness of these polities and the superiority of Greek hoplites over their Near Eastern counterparts. I demonstrate that the purported superiority of Greek heavy infantry has been exaggerated by Greco-Roman authors. Furthermore, close examination of Greek mercenary service reveals that the recruitment of Greek soldiers was not the purpose of Achaemenid foreign policy in Greece and the Aegean, but was instead an indication of the political subordination of prominent Greek citizens and poleis, conducted through the social institution of xenia, to Persian satraps and kings. -

A Collection of Exceptional Ancient Greek Coins

A Collection of Exceptional Ancient Greek Coins To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Book Room 34-35 New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Monday 24 October 2011 at 11.00 am Public viewing: Morton & Eden, 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Thursday 20 October 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Friday 21 October 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Sunday 23 October 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 51 Price £15 Enquiries: Tom Eden or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 160 (front); Lot 166 (back); Lot 126 (inside front and back covers) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Online Bidding Morton & Eden Ltd offer an online bidding service via www.the-saleroom.com. This is provided on the understanding that Morton & Eden Ltd shall not be responsible for errors or failures to execute internet bids for reasons including but not limited to: i) a loss of internet connection by either party; ii) a breakdown or other problems with the online bidding software; iii) a breakdown or other problems with your computer, system or internet connection. -

Celtic Coins and Their Archetypes

Celtic Coins and their Archetypes The Celts dominated vast parts of Europe from the beginning of the 5th century BC. On their campaigns they clashed with the Etruscans, the Romans and the Greeks, they fought as mercenaries under Philip II and Alexander the Great. On their campaigns the Celts encountered many exotic things – coins, for instance. From the beginning of the 3rd century, the Celts started to strike their own coins Initially, their issued were copies of Greek, Roman and other money. Soon, however, the Celts started to modify the Greek and Roman designs according to their own taste and fashion. By sheer abstraction they managed to transform foreign models into typically Celtic artworks, which are often almost modern looking. 1 von 27 www.sunflower.ch Kingdom of Macedon, Alexander III the Great (336-323 BC) in the Name of Philip II, Stater, c. 324 BC, Colophon Denomination: Stater Mint Authority: King Alexander III of Macedon Mint: Colophon Year of Issue: -324 Weight (g): 8.6 Diameter (mm): 19.0 Material: Gold Owner: Sunflower Foundation Through decades of warfare, King Philip II had turned Macedon into the leading power of the Greek world. In the summer of 336 BC he was assassinated, however, and succeeded by his son Alexander, who would later be known as "the Great." This coin was minted one year before Alexander's death. It bears a beautiful image of Apollo. The coin is a so-called Philip's stater, as Alexander's father Philip had already issued them for diplomatic purposes (bribery thus) and for the pay of his mercenaries. -

Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: a Socio-Cultural Perspective

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective Nicholas D. Cross The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1479 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INTERSTATE ALLIANCES IN THE FOURTH-CENTURY BCE GREEK WORLD: A SOCIO-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE by Nicholas D. Cross A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Nicholas D. Cross All Rights Reserved ii Interstate Alliances in the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ __________________________________________ Date Jennifer Roberts Chair of Examining Committee ______________ __________________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Joel Allen Liv Yarrow THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross Adviser: Professor Jennifer Roberts This dissertation offers a reassessment of interstate alliances (συµµαχία) in the fourth-century BCE Greek world from a socio-cultural perspective. -

Alexander the Great – the Father of the First International Currency

Alexander the Great – the Father of the First International Currency Alexander the Great is of big importance to the history of coinage. After his ascension to the throne following the assassination of his father Philip II, Alexander adopted the Attic coinage standard. From then on, he thus had his silver coins struck after the tetradrachms from Athens, the at that time most successful international trading currency. Wherever he went on his later campaigns, Alexander issued and circulated his own coins. They were of an until then unknown uniformity, despite some stylistic variations and although they were struck in hundreds of mints throughout Europe and Asia. Alexander's silver coins always bore the head of Heracles on the obverse, the mythical ancestor of the Argead dynasty, as the royal house of Macedon called itself. The gold pieces showed the head of the goddess Athena on the obverse and Nike, the goddess of Victory, on the reverse. 1 von 9 www.sunflower.ch Kingdom of Macedon, Alexander III the Great (336-323 BC), Stater, 330-320 BC, Amphipolis Denomination: Stater Mint Authority: King Alexander III of Macedon Mint: Amphipolis Year of Issue: -330 Weight (g): 9 Diameter (mm): 19.0 Material: Gold Owner: Sunflower Foundation This stater of Alexander the Great bears on the obverse the Greek goddess Athena and on the reverse Nike, the Greek personification of victory. Alexander was only 20 years of age when he assumed power in Macedon. In the thirteen years of his rule, he invaded and conquered enormous territories and created an empire from Greece to India.