Harvard Mountaineering 30

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

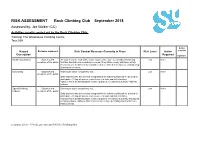

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018 Assessed by: Joe Walker (CC) Activities usually carried out by the Rock Climbing Club: Training: The Warehouse Climbing Centre Tour: N/A Action Hazard Persons exposed Risk Control Measures Currently in Place Risk Level Action complete Description Required signature Bouldering (Indoor) Students and All students of the club will be made aware of the safe use of indoor bouldering Low None members of the public facilities and will be immediately removed if they fail to comply with these safety measures or a member of the committee believe that their actions are endangering themselves or others. Auto-Belay Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay climbing indoors. Speed Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay and speed climbing indoors, ability to differentiate between speed climbing and normal auto belay systems. y:\sports\2018 - 19\risk assessments\UGSU Climbing RA Top Rope Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Med None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate in belaying - Fitting a harness, tying of a threaded figure of 8 knot, correct use of a belay device, correct belaying technique, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to top rope climbing indoors. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan GEOLOGY of the SCOTT GLACIER and WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA

This dissertation has been /»OOAOO m icrofilm ed exactly as received MINSHEW, Jr., Velon Haywood, 1939- GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTT GLACIER AND WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 Geology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTT GLACIER AND WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Velon Haywood Minshew, Jr. B.S., M.S, The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by -Adviser Department of Geology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report covers two field seasons in the central Trans- antarctic Mountains, During this time, the Mt, Weaver field party consisted of: George Doumani, leader and paleontologist; Larry Lackey, field assistant; Courtney Skinner, field assistant. The Wisconsin Range party was composed of: Gunter Faure, leader and geochronologist; John Mercer, glacial geologist; John Murtaugh, igneous petrclogist; James Teller, field assistant; Courtney Skinner, field assistant; Harry Gair, visiting strati- grapher. The author served as a stratigrapher with both expedi tions . Various members of the staff of the Department of Geology, The Ohio State University, as well as some specialists from the outside were consulted in the laboratory studies for the pre paration of this report. Dr. George E. Moore supervised the petrographic work and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr. J. M. Schopf examined the coal and plant fossils, and provided information concerning their age and environmental significance. Drs. Richard P. Goldthwait and Colin B. B. Bull spent time with the author discussing the late Paleozoic glacial deposits, and reviewed portions of the manuscript. -

Fall 12 Web Master.Txt

Student name Sex City County State Country Level High School Honor Roll Abbott, Logan M Wichita SG KS USA Junior Maize High School School of Pharmacy Abbott, Taylor F Lawrence DG KS USA Junior Lawrence High School College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Abdouch, Macrina F Omaha NE USA Senior Millard North High School School of Architecture, Design and Planning Abel, Hilary F Wakefield CY KS USA Freshman Junction City Senior High Sch College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Abi, Binu F Olathe JO KS USA Prof 1 Olathe South High School School of Pharmacy Ablah, George M Wichita SG KS USA Junior Andover High School College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Ablah, Patricia F Wichita SG KS USA Sophomore Andover High School School of Business Abraham, Christopher M Overland Park JO KS USA Freshman Blue Valley Northwest High Sch College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Abrahams, Brandi F Silver Lake SN KS USA Freshman Silver Lake Jr/Sr High School School of Business Absher, Cassie F Eudora DO KS USA Senior College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Abshire, Christopher M Overland Park JO KS USA Sophomore Blue Valley High School School of Engineering Acharya, Birat M Olathe JO KS USA Junior Olathe East High School College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Acosta Caballero, Andrea F Asuncion PRY Senior College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Adair, Sarah F Olathe JO KS USA Junior Olathe South High School College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Adams, Caitlin F Woodridge IL USA Freshman South HS in Downer's Grove College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Adams, Nancy F Lees Summit MO USA Senior Blue Springs -

1961 Climbers Outing in the Icefield Range of the St

the Mountaineer 1962 Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office in Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during March and December by THE MOUNTAINEERS, P. 0. Box 122, Seattle 11, Wash. Clubroom is at 523 Pike Street in Seattle. Subscription price is $3.00 per year. The Mountaineers To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of Northwest America; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfillment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of outdoor Zif e. EDITORIAL STAFF Nancy Miller, Editor, Marjorie Wilson, Betty Manning, Winifred Coleman The Mountaineers OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES Robert N. Latz, President Peggy Lawton, Secretary Arthur Bratsberg, Vice-President Edward H. Murray, Treasurer A. L. Crittenden Frank Fickeisen Peggy Lawton John Klos William Marzolf Nancy Miller Morris Moen Roy A. Snider Ira Spring Leon Uziel E. A. Robinson (Ex-Officio) James Geniesse (Everett) J. D. Cockrell (Tacoma) James Pennington (Jr. Representative) OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES : TACOMA BRANCH Nels Bjarke, Chairman Wilma Shannon, Treasurer Harry Connor, Vice Chairman Miles Johnson John Freeman (Ex-Officio) (Jr. Representative) Jack Gallagher James Henriot Edith Goodman George Munday Helen Sohlberg, Secretary OFFICERS: EVERETT BRANCH Jim Geniesse, Chairman Dorothy Philipp, Secretary Ralph Mackey, Treasurer COPYRIGHT 1962 BY THE MOUNTAINEERS The Mountaineer Climbing Code· A climbing party of three is the minimum, unless adequate support is available who have knowledge that the climb is in progress. -

Gear Brands List & Lexicon

Gear Brands List & Lexicon Mountain climbing is an equipment intensive activity. Having good equipment in the mountains increases safety and your comfort level and therefore your chance of having a successful climb. Alpine Ascents does not sell equipment nor do we receive any outside incentive to recommend a particular brand name over another. Our recommendations are based on quality, experience and performance with your best interest in mind. This lexicon represents years of in-field knowledge and experience by a multitude of guides, teachers and climbers. We have found that by being well-equipped on climbs and expeditions our climbers are able to succeed in conditions that force other teams back. No matter which trip you are considering you can trust the gear selection has been carefully thought out to every last detail. People new to the sport often find gear purchasing a daunting chore. We recommend you examine our suggested brands closely to assist in your purchasing decisions and consider renting gear whenever possible. Begin preparing for your trip as far in advance as possible so that you may find sale items. As always we highly recommend consulting our staff of experts prior to making major equipment purchases. A Word on Layering One of the most frequently asked questions regarding outdoor equipment relates to clothing, specifically (and most importantly for safety and comfort), proper layering. There are Four basic layers you will need on most of our trips, including our Mount Rainier programs. They are illustrated below: Underwear -

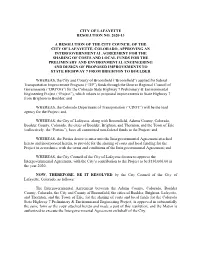

Resolution No. 2020-13

CITY OF LAFAYETTE RESOLUTION NO. 2020-13 A RESOLUTION OF THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF LAFAYETTE, COLORADO, APPROVING AN INTERGOVERNMENTAL AGREEMENT FOR THE SHARING OF COSTS AND LOCAL FUNDS FOR THE PRELIMINARY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN OF PROPOSED IMPROVEMENTS TO STATE HIGHWAY 7 FROM BRIGHTON TO BOULDER WHEREAS, the City and County of Broomfield (“Broomfield”) applied for federal Transportation Improvement Program (“TIP”) funds through the Denver Regional Council of Governments (“DRCOG”) for the Colorado State Highway 7 Preliminary & Environmental Engineering Project (“Project”), which relates to proposed improvements to State Highway 7 from Brighton to Boulder; and WHEREAS, the Colorado Department of Transportation (“CDOT”) will be the lead agency for the Project; and WHEREAS, the City of Lafayette, along with Broomfield, Adams County, Colorado, Boulder County, Colorado, the cities of Boulder, Brighton, and Thornton, and the Town of Erie (collectively, the “Parties”), have all committed non-federal funds to the Project; and WHEREAS, the Parties desire to enter into the Intergovernmental Agreement attached hereto and incorporated herein, to provide for the sharing of costs and local funding for the Project in accordance with the terms and conditions of the Intergovernmental Agreement; and WHEREAS, the City Council of the City of Lafayette desires to approve the Intergovernmental Agreement, with the City’s contribution to the Project to be $130,000.00 in the year 2020. NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED by the City Council -

The Complete Script

Feb rua rg 1968 North Cascades Conservation Council P. 0. Box 156 Un ? ve rs i ty Stat i on Seattle, './n. 98 105 SCRIPT FOR NORTH CASCAOES SLIDE SHOW (75 SI Ides) I ntroduct Ion : The North Cascades fiountatn Range In the State of VJashington Is a great tangled chain of knotted peaks and spires, glaciers and rivers, lakes, forests, and meadov;s, stretching for a 150 miles - roughly from Pt. fiainier National Park north to the Canadian Border, The h undreds of sharp spiring mountain peaks, many of them still unnamed and relatively unexplored, rise from near sea level elevations to seven to ten thousand feet. On the flanks of the mountains are 519 glaciers, in 9 3 square mites of ice - three times as much living ice as in all the rest of the forty-eight states put together. The great river valleys contain the last remnants of the magnificent Pacific Northwest Rain Forest of immense Douglas Fir, cedar, and hemlock. f'oss and ferns carpet the forest floor, and wild• life abounds. The great rivers and thousands of streams and lakes run clear and pure still; the nine thousand foot deep trencli contain• ing 55 mile long Lake Chelan is one of tiie deepest canyons in the world, from lake bottom to mountain top, in 1937 Park Service Study Report declared that the North Cascades, if created into a National Park, would "outrank in scenic quality any existing National Park in the United States and any possibility for such a park." The seven iiiitlion acre area of the North Cascades is almost entirely Fedo rally owned, and managed by the United States Forest Service, an agency of the Department of Agriculture, The Forest Ser• vice operates under the policy of "multiple use", which permits log• ging, mining, grazing, hunting, wt Iderness, and alI forms of recrea• tional use, Hov/e ve r , the 1937 Park Study Report rec ornmen d ed the creation of a three million acre Ice Peaks National Park ombracing all of the great volcanos of the North Cascades and most of the rest of the superlative scenery. -

Saddlebrooke Hiking Club Hike Database 11-15-2020 Hike Location Hike Rating Hike Name Hike Description

SaddleBrooke Hiking Club Hike Database 11-15-2020 Hike Location Hike Rating Hike Name Hike Description AZ Trail B Arizona Trail: Alamo Canyon This passage begins at a point west of the White Canyon Wilderness on the Tonto (Passage 17) National Forest boundary about 0.6 miles due east of Ajax Peak. From here the trail heads west and north for about 1.5 miles, eventually dropping into a two- track road and drainage. Follow the drainage north for about 100 feet until it turns left (west) via the rocky drainage and follow this rocky two-track for approximately 150 feet. At this point there is new signage installed leading north (uphill) to a saddle. This is a newly constructed trail which passes through the saddle and leads downhill across a rugged and lush hillside, eventually arriving at FR4. After crossing FR4, the trail continues west and turns north as you work your way toward Picketpost Mountain. The trail will continue north and eventually wraps around to the west side of Picketpost and somewhat paralleling Alamo Canyon drainage until reaching the Picketpost Trailhead. Hike 13.6 miles; trailhead elevations 3471 feet south and 2399 feet north; net elevation change 1371 feet; accumulated gains 1214 northward and 2707 feet southward; RTD __ miles (dirt). AZ Trail A Arizona Trail: Babbitt Ranch This passage begins just east of the Cedar Ranch area where FR 417 and FR (Passage 35) 9008A intersect. From here the route follows a pipeline road north to the Tub Ranch Camp. The route continues towards the corrals (east of the buildings). -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

December Resume - 1 - 2450’ from N Line and 1150’ from W Line of S7

TO ALL PERSONS INTERESTED IN WATER APPLICATIONS IN WATER DIVISION 1: Pursuant to CRS, 37-92-302, you are hereby notified that the following pages comprise a resume of applications and amended applications filed in the office of the Water Clerk for Water Division No. 1 during the month of December, 2001. 2001CW248 CLARENCE AND GLADYS KUNZ, P.O. Box 1867, Silverthorn, CO 80498. Application for Change of Water Right, IN JEFFERSON COUNTY. Kunz Well No. 2 decreed 4/15/1974 in Case No. W-4792, Water Division 1. Decreed point of diversion: NW1/4NE1/4, S23, T6S, R71W, 6th P.M., at a point 428’ E and 124’ S of the N1/4 corner of said section 23. Source: Groundwater Appropriation: 5/1/1954 Amount: 0.02 cfs (9 gpm) Historic use: Decreed use is for domestic, fire protection, recreation, stockwatering and irrigation. Actual historic use has been for domestic at a maximum pumping rate of 7 gpm with an annual limit of one acre-foot under well permit No. 113216 and 113216A. Well permit and map attached to this application. Proposed change: Change of use: Abandon the recreation use of the well, permit No. 113216 and 113216A, originally decreed as Kunz Well No. 2 in case No. W-4792. Said permit allows a maximum of one acre foot. (2 pages) 2001CW249 JACOB KAMMERZELL, 25090 WCR 15, Johnstown, CO 80534. Application for Water Rights (Surface), IN WELD COUNTY. Adams Delta Seepage Ditch originates at the property located in S1/2SE1/4, S30, T5N, R67W, 6th P.M. It originates from a point of 1260+ or – from S30 East boundary line and on the S side of WCR 151/4. -

The K-Pop Wave: an Economic Analysis

The K-pop Wave: An Economic Analysis Patrick A. Messerlin1 Wonkyu Shin2 (new revision October 6, 2013) ABSTRACT This paper first shows the key role of the Korean entertainment firms in the K-pop wave: they have found the right niche in which to operate— the ‘dance-intensive’ segment—and worked out a very innovative mix of old and new technologies for developing the Korean comparative advantages in this segment. Secondly, the paper focuses on the most significant features of the Korean market which have contributed to the K-pop success in the world: the relative smallness of this market, its high level of competition, its lower prices than in any other large developed country, and its innovative ways to cope with intellectual property rights issues. Thirdly, the paper discusses the many ways the K-pop wave could ensure its sustainability, in particular by developing and channeling the huge pool of skills and resources of the current K- pop stars to new entertainment and art activities. Last but not least, the paper addresses the key issue of the ‘Koreanness’ of the K-pop wave: does K-pop send some deep messages from and about Korea to the world? It argues that it does. Keywords: Entertainment; Comparative advantages; Services; Trade in services; Internet; Digital music; Technologies; Intellectual Property Rights; Culture; Koreanness. JEL classification: L82, O33, O34, Z1 Acknowledgements: We thank Dukgeun Ahn, Jinwoo Choi, Keun Lee, Walter G. Park and the participants to the seminars at the Graduate School of International Studies of Seoul National University, Hanyang University and STEPI (Science and Technology Policy Institute). -

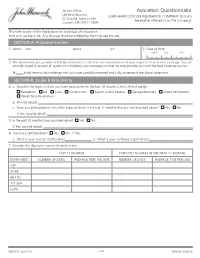

Avocation Questionnaire

Service Office: Avocation Questionnaire Life New Business JOHN HANCOCK LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY (U.S.A.) 30 Dan Rd, Suite 55765 (hereinafter referred to as The Company) Canton, MA 02021-2809 This form is part of the Application for Individual Life Insurance. Print and use black ink. Any changes must be initialed by the Proposed Insured. SECTION A: Proposed Insured 1. Name FIRST MIDDLE LAST 2. Date of Birth MONTH DAY YEAR 3. The information you provide in this Questionnaire is critical to our consideration of your request for insurance coverage. You are strongly urged to answer all questions completely and accurately so that we may provide you with the best coverage we can. X Initial here to acknowledge that you have carefully reviewed and fully understand the above statement. SECTION B: Scuba & Skin Diving 4. a. Describe the types of dives you have participated in the last 12 months (check all that apply): Recreation Ice Cave Construction Search and/or Rescue Salvage/Recovery Wreck Penetration Wreck Non-Penetration b. Provide details c. Have you participated in any other types of dives in the last 12 months that are not described above? Yes No If Yes, provide details 5. In the past 12 months, have you dived alone? Yes No If Yes, provide details 6. Are you a certified diver? Yes No If Yes, a. What is your level of certification? b. What is your certifying organization? 7. Describe the dives you have performed in the: LAST 12 MONTHS EXPECTED TO MAKE IN THE NEXT 12 MONTHS DEPTH (FEET) NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE <30 30-65 66-130 131-200 >200 NB5010FL (03/2016) 1 of 4 VERSION (03/2016) SECTION C: Automobile, Motorcycle and Power Boat Racing 8.