The Rochdale Pioneers and the Co-Operative Principles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heywood Distribution Park OL10 2TT, Greater Manchester

Heywood Distribution Park OL10 2TT, Greater Manchester TO LET - 148,856 SQ FT New self-contained production /distribution unit Award winning 24 hour on-site security, CCTV and gatehouse entry 60m service yard 11 dock and two drive in loading doors 1 mile from M66/J3 4 miles from M62/J18 www.heywoodpoint.co.uk Occupiers include: KUEHNE+NAGEL DPD Group Wincanton K&N DFS M66 / M62 Fowler Welch Krispy Kreme Footasylum Eddie Stobart Paul Hartmann 148,000 sq ft Argos AVAILABLE NOW Main Aramex Entrance Moran Logistics Iron Mountain 60m 11 DOCK LEVELLERS LEVEL ACCESS LEVEL ACCESS 148,856 sq ft self-contained distribution building Schedule of accommodation TWO STOREY OFFICES STOREY TWO Warehouse 13,080 sq m 140,790 sq ft Ground floor offices 375 sq m 4,033 sq ft 90.56m First floor offices 375 sq m 4,033 sq ft 148,000 sq ft Total 13,830 sq m 148,856 sq ft SPACES PARKING 135 CAR 147.65m Warehouse Offices External Areas 5 DOCK LEVELLERS 50m BREEAM “very good” 11 dock level access doors Fully finished to Cat A standard LEVEL ACCESS 60m service yardLEVEL ACCESS EPC “A” rating 2 level access doors 8 person lift 135 dedicated car parking spaces 12m clear height 745kVA electricity supply Heating and comfort cooling Covered cycle racks 50kN/sqm floor loading 15% roof lights 85.12m 72.81m TWO STOREY OFFICES 61 CAR PARKING SPACES M66 Rochdale Location maps Bury A58 Bolton A58 M62 A56 A666 South Heywood link road This will involve the construction of a new 1km road between the motorway junction and A58 M61 Oldham A new link road is proposed which will Hareshill Road, together with the widening M60 A576 M60 provide a direct link between Heywood and upgrading of Hareshill Road. -

Convenience Is Here with CO-OP Shared Branching!

Convenience is here with CO-OP Shared Branching! Personalized service is a major benefit of banking at Capstone Federal Credit Union, and you don’t have to sacrifice convenience to get it. Take advantage of Capstone FCU’s shared branching services through CO-OP Shared Branch. Access your account at any of the 5,100 credit union branches nationwide. The national CO-OP Shared Branch network links participating credit unions electronically, allowing credit union members to do “branch banking,” even when the branch near you doesn’t belong to Capstone FCU. This is a huge benefit to Capstone FCU members who travel, whose workplaces don’t coincide with our branch locations, or who simply enjoy Look for the CO- the convenience of expanded access. Wherever you are across the OP Shared Branch logo to find shared country, chances are good there’s a shared branch near you. branches near you. Shared branching is yet another example of credit union membership offering the best of both worlds—individualized attention and nationwide availability. The cooperative spirit of credit unions allows them to work with each other in ways that competing banks typically do not. Visit www.co-opsharedbranch.org or download the Shared Branch Locator app for iPhone or Android to find branches nearest you. You can also look for the “CO-OP Shared Branch” logo on the door of any credit union branch. At a CO-OP Shared Branch location, you can: . Make deposits and withdrawals . Make loan payments . Make credit card payments . Access VISA® or MasterCard® funds Many shared branches also offer transfers, statement histories, money orders, traveler’s checks and notary services. -

Financial Strength Connecting to a Stronger Future for Credit Unions

2012 Financial Strength Connecting to a Stronger Future for Credit Unions Born in 1935 out of the emerging credit union In 2012, we improved our financial strength, enhanced products movement, during the depths of the Great Depression, and services, and invested in CUNA Mutual Group endeavored to fulfill the vision the markets we serve and the communities in which we operate. of credit union pioneers. Driven by the belief that These results are a direct reflection of our insurance was as fundamental to the movement original mission. as savings and lending, CUNA Mutual Group would Jeff Post President & CEO become the leading provider of credit life insurance in the United States in just two years. Today, CUNA Mutual Group is a Fortune 1000 company, with assets of more than $17 billion. Our products have expanded to include Life Insurance, Annuities, Retirement Income and Investments. Our achievements are directly attributable to a single principle: an enduring commitment to the success of credit unions, their members and our policyholders. Total Revenue Total Revenue Operating Revenue by Product 2012 Results: Delivering on Our Commitment Total(in billions) Revenue Operating Revenue by Product (in billions) Operating Revenue by Product (in billions) 3.1 3.0 3.1 to Policyholders 3.0 3.1 2.8 3.0 2.7 2.8 2.6 2.7 2.8 The external challenges in 2012 remained formidable with 2.6 2.7 a sluggish national economy and the continuing struggle at 2.6 the federal level to address the fiscal issues. Severe weather events also presented difficult obstacles to overcome, from the drought in the Midwest’s Corn Belt to Superstorm Sandy that battered the East Coast. -

The Royal Oldham Hospital, OL1

The Royal Oldham Hospital, OL1 2JH Travel Choices Information – Patient and Visitor Version Details Notes and Links Site Map Site Map – Link to Pennine Acute website Bus Stops, Services Bus Stops are located on the roads alongside the hospital site and are letter and operators coded. The main bus stops are on Rochdale Road and main bus service is the 409 linking Rochdale, Oldham and Ashton under Lyne. Also, see further Bus Operators serving the hospital are; information First Greater Manchester or on Twitter following. Rosso Bus Stagecoach Manchester or on Twitter The Transport Authority and main source of transport information is; TfGM or on Twitter ; TfGM Bus Route Explorer (for direct bus routes); North West Public Transport Journey Planner Nearest Metrolink The nearest stops are at Oldham King Street or Westwood; Tram Stops Operator website, Metrolink or on Twitter Transport Ticketing Try the First mobile ticketing app for smartphones, register and buy daily, weekly, monthly or 10 trip bus tickets on your phone, click here for details. For all bus operator, tram and train tickets, visit www.systemonetravelcards.co.uk. Local Link – Users need to be registered in advance (online or by phone) and live within Demand Responsive the area of service operation. It can be a minimum of 2 hours from Door to Door registering to booking a journey. Check details for each relevant service transport (see leaflet files on website, split by borough). Local Link – Door to Door Transport (Hollinwood, Coppice & Werneth) Ring and Ride Door to door transport for those who find using conventional public transport difficult. -

786-1 Credit for Reinsurance Model Regulation

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—Summer 2019 CREDIT FOR REINSURANCE MODEL REGULATION Table of Contents Section 1. Authority Section 2. Purpose Section 3. Severability Section 4. Credit for Reinsurance—Reinsurer Licensed in this State Section 5. Credit for Reinsurance—Accredited Reinsurers Section 6. Credit for Reinsurance—Reinsurer Domiciled in Another State Section 7. Credit for Reinsurance—Reinsurers Maintaining Trust Funds Section 8. Credit for Reinsurance––Certified Reinsurers Section 9. Credit for Reinsurance—Reciprocal Jurisdictions Section 10. Credit for Reinsurance Required by Law Section 11. Asset or Reduction from Liability for Reinsurance Ceded to Unauthorized Assuming Insurer Not Meeting the Requirements of Sections 4 Through 10 Section 12. Trust Agreements Qualified Under Section 11 Section 13. Letters of Credit Qualified Under Section 11 Section 14. Other Security Section 15. Reinsurance Contract Section 16. Contracts Affected Form AR-1 Certificate of Assuming Insurer Form CR-1 Certificate of Certified Reinsurer Form RJ-1 Certificate of Reinsurer Domiciled in Reciprocal Jurisdiction Form CR-F Form CR-S Section 1. Authority This regulation is promulgated pursuant to the authority granted by Sections [insert applicable section number] and [insert applicable section number] of the Insurance Code. Section 2. Purpose The purpose of this regulation is to set forth rules and procedural requirements that the commissioner deems necessary to carry out the provisions of the [cite state law equivalent to the Credit for Reinsurance Model Law (#785)] (the Act). The actions and information required by this regulation are declared to be necessary and appropriate in the public interest and for the protection of the ceding insurers in this state. -

Deposit Insurance

Information about your DEPOSIT INSURANCE American Share Insurance insures each and every account of an individual member up to $250,000 without any limitation as to the number of accounts held. Your Insured Funds* Member’s Accounts Amount Covered Savings/Regular Share $ 250,000 Checking/Share Draft $ 250,000 Money Market $ 250,000 CD/Share Certificate #1 $ 250,000 CD/Share Certificate #2 $ 250,000 IRA $ 250,000 TOTAL INSURED $ 1,500,000 *Example only AmericanShare.com 5656 Frantz Road | Dublin, OH 43017 800.521.6342 American Share Insurance is a member-owned non- federal deposit insurer. This institution is not federally insured, or insured by any state government. MEMBERS’ ACCOUNTS ARE NOT INSURED OR GUARANTEED BY ANY GOVERNMENT OR GOVERNMENT-SPONSORED AGENCY. Form 100 © 01/16 We are pleased to inform you American Share is selective as to whom that your deposit accounts it insures, and to qualify for its deposit in this credit union are insurance the credit union must comply with American Share’s rigid underwriting insured up to $250,000 per standards. Also, American Share’s insurance account by American Share policy requires that every quarter the credit Insurance. American Share is union submit financial statements in order to a credit union-owned private continue coverage. Individual policies are not organization whose only provided to members, and there is no direct business is to provide deposit cost to you for this coverage. It is important to note that deposit insurance is payable only insurance to credit unions. upon the failure and liquidation of the credit union. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Thursday Volume 513 15 July 2010 No. 33 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 15 July 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 1069 15 JULY 2010 1070 what can be done to speed up transactions. I know that House of Commons my right hon. Friend the Minister for Housing is looking at ways to speed up the introduction of e-conveyancing. Thursday 15 July 2010 Dr Alan Whitehead (Southampton, Test) (Lab): Why has the Secretary of State decided, alongside the abolition The House met at half-past Ten o’clock of HIPs, that energy performance certificates should no longer be required at the point when a house is initially viewed for purchase? Does he intend to downgrade the PRAYERS importance of those as well? [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Mr Pickles: Gracious, no—indeed, under our green deal, energy certificates will perform a much more important role. They will be about bringing the price of energy down and ensuring that somebody with a house Oral Answers to Questions that has a good energy certificate does well, because we want to get houses on to the market. We will insist that the energy certificate be commissioned and in place before the sale takes place. It is about speeding things COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT up—the hon. -

![Activity 6 [COOPERATIVES in the SCHOOLS]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3938/activity-6-cooperatives-in-the-schools-533938.webp)

Activity 6 [COOPERATIVES in the SCHOOLS]

Day 1 – Activity 6 [COOPERATIVES IN THE SCHOOLS] Activity 6 - Cooperative Facts Time: 20 minutes Objective: Students will learn some basic history and facts about cooperatives. Step 1: Instruct students to take out their handouts called “Cooperative Fact Sheets.” Give them 3-5 minutes to read them silently to themselves. Step 2: Tell students that they will play, “Find the Fact”. Have each material handler come up and get a white board for each cooperative. If the teacher does not have white boards, then have the reporter take out a notebook and a marker. Tell students that each group will get 30 seconds to find the answer to a fact question and write it on their whiteboard or notebook. At the end of the 30 seconds, each team will hold up their answers and accumulate points for each correct fact found. Team will use their “Cooperative Fact Sheet” to help them with this game. Step 3: Give an example so that students understand the game. “Who is the founding father that organized the first successful US cooperative in 1752?” After 30 seconds, call time and have students hold up their answers. For the teams who wrote, “Benjamin Franklin” say, these teams would have gotten one point. Write the team names on the board to keep track of points. Step 4: When teams understand the rules, begin the game. Below are sample questions/answers: 1. What year was the first cooperative in Wisconsin formed? A: 1841 2. What is the word that means, “The money left over after you pay all your expenses?” A: profit 3. -

Dr. William King and the Co-Operator, 1828-1830

Dr. William King AN!) THK ,Cp-operator i828^i83o I Edited by T. W. MERCER, nn-: CO-OPERATIVE UNWN Liv Hfornia MO!,VOAKE HOCSI', HANOV«R STRLl.T onal ity Dr. WILLIAM KING AND THE CO-OPERATOR 1828-1830 Dk. William King. From a Photoiiraph by his friend, Mons. L. Leuliette, i Frontispiece, Dr. WILLIAM KING AND THE CO-OPERATOR 1828-1830 With Introduction and Xotes by T. W. MERCER MANCHESTER: The Co-operative Union Limitku, Holvoake House. Hanover Street. 1922. "Co-operation is a voluntar}' act, and all the power in the world cannot make it compulsory ; nor is it desir- able that it should depend upon any power but its own." —The Co-operator, 1829. 1 C7S PREFATORY NOTE. Fifty-Fourth Annual \Y/HEN it was agreed that the Co-operative Congress should be held at Brighton of in June, 1922, the General Publications Committee the Co-operative Union decided that the time was " Co-operator," a small opportune to . reprint The co-operative periodical, first published in Brighton by Dr. William King nearly a century ago. In consequence of that decision, the present volume has been prepared. It includes a faithful reprint of " Co-operator a the twenty-eight numbers of The " ; sketch of Dr. King's Ufe and teaching, containing notes information not previously published ; and a few contributed by the present writer. Several letters written by Dr. King to other early co-operators are also here reprinted. In "The Co-operator" both spelling and punctuation have been left as they are in the original edition, but a few obvious printer's errors have been corrected. -

Mapping: Key Figures National Report: United Kingdom Ica-Eu Partnership

MAPPING: KEY FIGURES NATIONAL REPORT: UNITED KINGDOM ICA-EU PARTNERSHIP TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT ........................................................................... 2 i. Historical background ........................................................................................... 2 ii. Public national statistics ....................................................................................... 4 iii. Research methodology......................................................................................... 5 II. KEY FIGURES ......................................................................................................... 6 iv. ICA member data ................................................................................................. 7 v. General overview .................................................................................................. 7 vi. Sector overview .................................................................................................... 8 III. GRAPHS................................................................................................................. 11 vii. Number of cooperatives by type of cooperative: ............................................... 11 viii. Number of memberships by type of cooperative: .............................................. 12 ix. Number of employees by type of cooperative: .................................................. 13 x. Turnover by type of cooperative in EUR: .......................................................... -

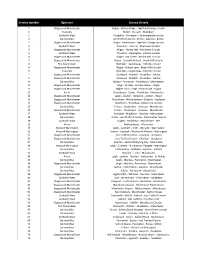

Sept 2020 All Local Registered Bus Services

Service number Operator Service Details 1 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Marus Bridge - Highfield Grange Circular 1 Transdev Bolton - Darwen - Blackburn 1 Go North West Piccadilly - Chinatown - Spinningfields circular 2 Diamond Bus intu Trafford Centre - Eccles - Swinton - Bolton 2 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Pemberton - Highfield Grange circular 2 Go North West Piccadilly - Victoria - Deansgate circular 3 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Norley Hall - Kitt Green Circular 3 Go North West Piccadilly - Deansgate - Victoria circular 4 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Kitt Green - Norley Hall Circular 5 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Springfield Road - Beech Hill Circular 6 First Manchester Rochdale - Queensway - Kirkholt circular 6 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Gidlow Lane - Beech Hill Circular 6 Transdev Rochdale - Queensway - Kirkholt circular 7 Stagecoach Manchester Stockport - Reddish - Droyslden - Ashton 7 Stagecoach Manchester Stockport - Reddish - Droylsden - Ashton 8 Diamond Bus Bolton - Farnworth - Pendlebury - Manchester 8 Stagecoach Manchester Leigh - Hindley - Hindley Green - Wigan 9 Stagecoach Manchester Higher Folds - Leigh - Platt Bridge - Wigan 10 Arriva Brookhouse - Eccles - Pendleton - Manchester 10 Stagecoach Manchester Leigh - Lowton - Golborne - Ashton - Wigan 11 Stagecoach Manchester Altrincham - Wythenshawe - Cheadle - Stockport 12 Stagecoach Manchester Middleton - Boarshaw - Moorclose circular 15 Diamond Bus Flixton - Davyhulme - Urmston - Manchester 15 Stagecoach Manchester Flixton - Davyhulme - Urmston - Manchester 17 -

17 Times Changed 17 17A

From 3 September Buses Replacement 17 Times changed 17 17A Easy access on all buses Rochdale Sudden Castleton Middleton Blackley Harpurhey Collyhurst Manchester From 3 September 2017 For public transport information phone 0161 244 1000 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays Operated by This timetable is available online at First Manchester www.tfgm.com PO Box 429, Manchester, M60 1HX ©Transport for Greater Manchester 17–1284–G17–7000–0817 Additional information Alternative format Operator details To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request First Manchester large print, Braille or recorded information Wallshaw Street, Oldham, OL1 3TR phone 0161 244 1000 or visit www.tfgm.com Telephone 0161 627 2929 Easy access on buses Travelshops Journeys run with low floor buses have no Manchester Piccadilly Gardens steps at the entrance, making getting on Mon to Sat 7am to 6pm and off easier. Where shown, low floor Sunday 10am to 6pm buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated Public hols 10am to 5.30pm space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the Manchester Shudehill Interchange bus. The bus operator will always try to provide Mon to Sat 7am to 7.30pm easy access services where these services are Sunday* 10am to 1.45pm and 2.30pm to 5.30pm scheduled to run. Middleton Bus Station Mon to Sat 8.30am to 1.15pm and 2pm to 4pm Using this timetable Sunday* Closed Timetables show the direction of travel, bus Rochdale Interchange numbers and the days of the week. Mon to Fri 7am to 5.30pm Main stops on the route are listed on the left.