Voices of New Music on National Public Radio: Radio Net, Radiovisions, and Maritime Rites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

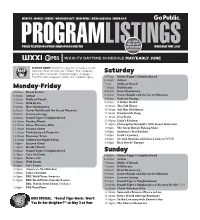

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

PARTNERS in Hope and Discovery Where the Power of Childhood Meets the Power of Research

PARTNERS in Hope and Discovery Where the power of childhood meets the power of research 2016 ANNUAL REPORT WHERE BREAKTHROUGHS HAPPEN The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the world’s premier biomedical research institution—and the breakthroughs that happen here are the first steps toward eradicating diseases, easing pain, and making better lives possible. None Inn residents of these medical advances would be participated possible without the people who drive them: children, families and caregivers, in 283 clinicians and staff—the community The CLINICAL Children’s Inn brings together. The Inn TRIALS provides relief, support, and strength to at the NIH these pioneers whose participation in in FY16 medical trials at the NIH can change the story for children around the world. Inn residents are a part of pediatric protocols in 15 of the 27 INSTITUTES and CENTERS at the NIH On the cover: Inn resident Reem, age 7 from Egypt, with her NIH physician, Dr. Neal Young. She is being treated for aplastic anemia at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. As partners in discovery and care, OUR VISION we strive for the day when no family endures the heartbreak of a seriously ill child. Letter from the Chair of the Board and Chief Executive Officer The Inn’s Board of Directors had an eventful We are so grateful to you: our donors, volunteers, year. We have worked diligently to restructure and friends, who help The Children’s Inn make a and prepare The Inn for the future, and recently profound impact on the lives of the NIH’s young- welcomed some talented new members to our est patients. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 116, 1996

The security of a trust, Fidelity service and expertise. A CLcuwLc Composition A conductor and his orchestra — together, they perform masterpieces. Fidelity Now Fidelity Personal Trust Services Pergonal can help you achieve the same harmony for your trust portfolio of Trudt $400,000 or more. Serviced You'll receive superior trust services through a dedicated trust officer, with the added benefit of Fidelity s renowned money management expertise. And because Fidelity is the largest privately owned financial services firm in the nation, you can rest assured that we will be there for the long term. Call Fidelity Personal Trust Serviced at 1-800-854-2829. You'll applaud our efforts. Trust Services offered by Fidelity Management Trust Company For more information, visit a Fidelity Investor Center near you: Boston - Back Bay • Boston - Financial District • Braintree, MA • Burlington, MA Fidelity Investments 17598.001 This should not be considered an offer to provide trust services in every state. Trust services vary by state. To determine whether Fidelity may provide trust services in your state, please call Fidelity at 1-800-854-2829. Investor Centers are branches of Fidelity Brokerage Services, Inc. Member NYSE, SIPC. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Sixteenth Season, 1996-97 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. R. Willis Leith, Jr., Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke. Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mrs. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson William M. Crozier, Jr. Julian T. -

Radiowaves Will Be Featuring Stories About WPR and WPT's History of Innovation and Impact on Public Broadcasting Nationally

ON AIR & ONLINE FEBRUARY 2017 Final Forte WPR at 100 Meet Alex Hall Centennial Events Internships & Fellowships Featured Photo Earlier this month, WPR's To the Best of Our Knowledge explored the relationship between love WPR Next" Initiative Explores New Program Ideas and evolution at a sold- out live show in Madison, We often get asked, "Where does WPR come up with ideas for its sponsored by the Center programs?" First and foremost, we're inspired by you, our listeners for Humans in Nature. and neighbors around the state. During our 100th year, we're looking Excerpts from the show, to create the public radio programs of the future with a new initiative which included storyteller called WPR Next. Dasha Kelly Hamilton (pictured), will be We're going to try out a few new show ideas focused on science, broadcast nationally on pop culture, life in Wisconsin, and more. You can help our producers the show later this month. develop these ideas by telling us what interests you about these topics. Sound Bites Do you love science? What interests you most ---- do you wonder about new research in genetics, life on other planets, or ice cover on Winter Pledge Drive the Great Lakes? What about pop culture? What makes a great Begins February 21 book, movie or piece of music, and who would you like to hear WPR's winter interviewed? How about life in Wisconsin? What do you want to membership drive is know about our state's culture and history? What other topics would February 21 through 25. -

Thesis a Uses and Gratification Study of Public Radio Audiences

THESIS A USES AND GRATIFICATION STUDY OF PUBLIC RADIO AUDIENCES Submitted by Scott D. Bluebond Speech and Theatre Arts Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring, 1982 COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY April 8, 1982 WE HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER OUR SUPERVISION BY Scott David Bluebond ENTITLED A USES AND GRATIFICATIONS STUDY OF PUBLIC RADIO AUDIENCES BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING IN PART REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts Committee on Graduate Work ABSTRACT OF THESIS A USES AND GRATIFICATION STUDY OF PUBLIC RADIO AUDIENCES This thesis sought to find out why people listen to public radio. The uses and gratifications data gathering approach was implemented for public radio audiences. Questionnaires were sent out to 389 listener/contrib utors of public radio in northern Colorado. KCSU-FM in Fort Collins and KUNC-FM in Greeley agreed to provide such lists of listener/contributors. One hundred ninety-two completed questionnaires were returned and provided the sample base for the study. The respondents indicated they used public radio primarily for its news, its special programming, and/or because it is entertaining. Her/his least likely reasons for using public radio are for diversion and/or to trans mit culture from one generation to the next. The remain ing uses and gratifications categories included in the study indicate moderate reasons for using public radio. Various limitations of the study possibly tempered the results. These included the sample used and the method used to analyze the data. Conducting the research necessary for completion of this study made evident the fact that more i i i research needs to be done to improve the uses and gratifica- tions approach to audience analysis. -

Edward R. Murrow

ABOUT AMERICA EDWARD R. MURROW JOURNALISM AT ITS BEST TABLE OF CONTENTS Edward R. Murrow: A Life.............................................................1 Freedom’s Watchdog: The Press in the U.S.....................................4 Murrow: Founder of American Broadcast Journalism....................7 Harnessing “New” Media for Quality Reporting .........................10 “See It Now”: Murrow vs. McCarthy ...........................................13 Murrow’s Legacy ..........................................................................16 Bibliography..................................................................................17 Photo Credits: University of Maryland; right, Digital Front cover: © CBS News Archive Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Page 1: CBS, Inc., AP/WWP. 12: Joe Barrentine, AP/WWP. 2: top left & right, Digital Collections and Archives, 13: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University; bottom, AP/WWP. Tufts University. 4: Louis Lanzano, AP/WWP. 14: top, Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 5 : left, North Wind Picture Archives; bottom, AP/WWP. right, Tim Roske, AP/WWP. 7: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Executive Editor: George Clack 8: top left, U.S. Information Agency, AP/WWP; Managing Editor: Mildred Solá Neely right, AP/WWP; bottom left, Digital Collections Art Director/Design: Min-Chih Yao and Archives, Tufts University. Contributing editors: Chris Larson, 10: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts Chandley McDonald University. Photo Research: Ann Monroe Jacobs 11: left, Library of American Broadcasting, Reference Specialist: Anita N. Green 1 EDWARD R. MURROW: A LIFE By MARK BETKA n a cool September evening somewhere Oin America in 1940, a family gathers around a vacuum- tube radio. As someone adjusts the tuning knob, a distinct and serious voice cuts through the airwaves: “This … is London.” And so begins a riveting first- hand account of the infamous “London Blitz,” the wholesale bombing of that city by the German air force in World War II. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site: Broadcasts by WNYC-FM (New York City) and KPFA-FM (Berkeley), 1991

CMYK 80811- 2 80817-2 [2 CDs] CHARLES AMIRKHANIAN (b. 1945) LOUDSPEAKERS CHARLES AMIRKHANIAN LOUDSPEAKERS DISC 1 [TT: 70:03] DISC 2 [TT: 61:30] Pianola (Pas de mains) (1997–2000) 39:51 1. Son of Metropolis 1. Corale Cattedrale 3:57 San Francisco (1997) 26:38 2. Pet Hop Solo 2:28 Loudspeakers 3. Valzer Provarollio 5:27 (for Morton Feldman) (1988–90) 34:32 4. Tochastic Music 2:18 2. Meyerbeer 4:35 5. Passaggio di Coltivadori 1:07 3. The Piece 5:26 6. Antheil Swoon 2:14 4. Voice Leading 6:51 7. Chaos of the Moderns (Presto) 4:24 5. Took Some Time 7:34 8. To a Nanka Rose 2:16 6. Such a Surface 3:33 9. A Rimsky Business 4:43 7. Pretty Pretty Macabre 3:08 10. Kiki Keys 10:39 8. Loudspeakers 3:24 11. Im Frühling (1989–90) 30:06 Im Frühling 1990, Son of Metropolis San Francisco ൿ 1997, Pianola ൿ 2000 A Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln Production New World Records, 20 Jay Street, Suite 1001, Brooklyn, NY 11201 Tel (212) 290-1680 Fax (646) 224-9638 [email protected] www.newworldrecords.org This compilation ൿ & © 2019 Anthology of Recorded Music, Inc. All rights reserved. Made in U.S.A. 21907.booklet.16 10/29/19 1:12 PM Page 2 HARLES AMIRKHANIAN (b. 1945) can be regarded as a central figure repetitive elements, but are more poetic, intuitive in their form and often in American music, and on several fronts. As a composer, he’s been impressionistic in their effect. -

Newsletter 1

The Newsletter of the Dialogue: Oral History Section Volume 6, Issue 1 Winter 2010 Society of American Archivists FROM THE CHAIR Mark Cave, The Historic New Orleans Collection Our section meeting in Austin anniversary. She is planning for on-site interviews to was a great success. 100 people take place at the annual conference in Washington. enjoyed the live interview conducted by Jim Fogerty Thank you to those of you who replied to our query with David Gracy. Jim did a to the section membership in October. We received wonderful job in conducting the really helpful information related to the interests and interview, and it was such a great needs of the section membership. This information way to honor Mr. Gracy for his will be helpful in the creation of an online survey, contributions to our profession. which will be a part of our website, and continually Our next section meeting promises to be equally gather information about the section’s membership. engaging. It is being planned by Vice Chair/Chair Past Chair Al Stein along with Nominating Committee Elect Joel Minor and will be devoted to oral history members Doug Boyd and Herman Trojanowski will be and human rights. looking for candidates for Vice Chair and two Steering Committee members for our next election, and will Lauren Kata has been busy since the Austin meeting also be reviewing our current bylaws. developing our SAA 75th Anniversary Oral History Project. Lauren has been named as the section’s A special thanks to Jennifer Eidson for preparing this representative on the 75th Anniversary Task Force, issue of Dialogue and for maintaining the section’s which is coordinating all the events surrounding the website. -

NEA-Annual-Report-1980.Pdf

National Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. 20506 Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1980. Respectfully, Livingston L. Biddle, Jr. Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. February 1981 Contents Chairman’s Statement 2 The Agency and Its Functions 4 National Council on the Arts 5 Programs 6 Deputy Chairman’s Statement 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 32 Expansion Arts 52 Folk Arts 88 Inter-Arts 104 Literature 118 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 140 Museum 168 Music 200 Opera-Musical Theater 238 Program Coordination 252 Theater 256 Visual Arts 276 Policy and Planning 316 Deputy Chairman’s Statement 318 Challenge Grants 320 Endowment Fellows 331 Research 334 Special Constituencies 338 Office for Partnership 344 Artists in Education 346 Partnership Coordination 352 State Programs 358 Financial Summary 365 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 366 Chairman’s Statement The Dream... The Reality "The arts have a central, fundamental impor In the 15 years since 1965, the arts have begun tance to our daily lives." When those phrases to flourish all across our country, as the were presented to the Congress in 1963--the illustrations on the accompanying pages make year I came to Washington to work for Senator clear. In all of this the National Endowment Claiborne Pell and began preparing legislation serves as a vital catalyst, with states and to establish a federal arts program--they were communities, with great numbers of philanthro far more rhetorical than expressive of a national pic sources. -

University of California Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EXTENDED FROM WHAT?: TRACING THE CONSTRUCTION, FLEXIBLE MEANING, AND CULTURAL DISCOURSES OF “EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES” A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by Charissa Noble March 2019 The Dissertation of Charissa Noble is approved: Professor Leta Miller, chair Professor Amy C. Beal Professor Larry Polansky Lori Kletzer Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Charissa Noble 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures v Abstract vi Acknowledgements and Dedications viii Introduction to Extended Vocal Techniques: Concepts and Practices 1 Chapter One: Reading the Trace-History of “Extended Vocal Techniques” Introduction 13 The State of EVT 16 Before EVT: A Brief Note 18 History of a Construct: In Search of EVT 20 Ted Szántó (1977): EVT in the Experimental Tradition 21 István Anhalt’s Alternative Voices (1984): Collecting and Codifying EVT 28evt in Vocal Taxonomies: EVT Diversification 32 EVT in Journalism: From the Musical Fringe to the Mainstream 42 EVT and the Classical Music Framework 51 Chapter Two: Vocal Virtuosity and Score-Based EVT Composition: Cathy Berberian, Bethany Beardslee, and EVT in the Conservatory-Oriented Prestige Economy Introduction: EVT and the “Voice-as-Instrument” Concept 53 Formalism, Voice-as-Instrument, and Prestige: Understanding EVT in Avant- Garde Music 58 Cathy Berberian and Luciano Berio 62 Bethany Beardslee and Milton Babbitt 81 Conclusion: The Plight of EVT Singers in the Avant-Garde -

ARSC Journal, Vol

NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO ARTS AND PERFORMANCE PROGRAMS By Frederica Kushner Definition and Scope For those who may be more familiar with commercial than with non-commercial radio and television, it may help to know that National Public Radio (NPR) is a non commercial radio network funded in major part through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and through its member stations. NPR is not the direct recipient of government funds. Its staff are not government employees. NPR produces programming of its own and also uses programming supplied by member stations; by other non commercial networks outside the U.S., such as the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC); by independent producers, and occasionally by commercial networks. The NPR offices and studios are located on M Street in Washington, D.C. Programming is distributed via satellite. The radio programs included in the following listing are "arts and performance." These programs were produced or distributed by the Arts Programming Department of NPR. The majority of the other programming produced by NPR comes from the News and Information Department. The names of the departments may change from time to time, but there always has been a dichotomy between news and arts programs. This introduction is not the proper place for a detailed history of National Public Radio, thus further explanation of the structure of the network can be dispensed with here. What does interest us are the varied types of programming under the arts and performance umbrella. They include jazz festivals recorded live, orchestra concerts from Europe as well as the U.S., drama of all sorts, folk music concerts, bluegrass, chamber music, radio game shows, interviews with authors and composers, choral music, programs illustrating the history of jazz, of popular music, of gospel music, and much, much more. -

Schola Hungarica Gregorian Chants in a Village Church Mp3, Flac, Wma

Schola Hungarica Gregorian Chants In A Village Church mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Gregorian Chants In A Village Church Country: Hungary Released: 1994 Style: Medieval MP3 version RAR size: 1420 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1389 mb WMA version RAR size: 1483 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 870 Other Formats: ADX VQF MP1 WMA AHX MP2 AA Tracklist 1 Introit: Rorate Caeli 2 Kyrie: Sanctorum Lumen - Gloria 3 Alleluia: Virga Jesse 4 Sequence: Mittit Ad Virginem 5 Offertory: Ave Maria 6 Praefatio - Sanctus 7 Cantio: Ave Verum Corpus 8 Oremus - Pater Noster - Agnus Dei 9 Communion: Ecce Virgo Concipiet 10 Cantio: Idvozlegy Istennek Szent Anyja 11 Palm Sunday Procession 12 Antiphon: Ante Sex Dies 13 Antiphon: Cum Audisset Populus 14 Antiphon: Fulgentibus Palmis 15 Antiphon: Cum Appropinquaret Dominus Hymn: Gloria, Laus Et Honor - Pueri Hebraeorum Tollentes - Antiphons: Pueri Hebraeorum 16 Vestimenta - Scriptum Est Enim 17 Antiphon: Turba Multa 18 Lectio: Epistolae Beati Pauli Apostoli 19 Trope: Triumphat Dei Filius Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Schola Gregorian Chants In A SLPD 12742 Hungaroton SLPD 12742 Hungary 1986 Hungarica Village Church (LP, Album) Related Music albums to Gregorian Chants In A Village Church by Schola Hungarica Monks Of The Abbey Of St. Thomas - A Treasury Of Gregorian Chant - Vol. III Schola Antiqua, Blackley • Jones - Music For Holy Week Schola Hungarica - Vízkereszt - Magyar Gregorián Énekek = Epiphany - Gregorian Chants From Hungary Schola Of The Hofburgkapelle, Vienna , Director Hubert Dopf - Gregorian Chant Hildegard Von Bingen, Schola Der Benediktinerinnenabtei St. Hildegard, Eibingen, Johannes Berchmans Göschl , Sr. Christiane Rath Osb - "O Vis Aeternitatis" - Vesper In Der Abtei St.