Beaudry-2006Oncj59

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Is a Copy of Correspondence with Manitouwadge From: Edo

From: Tabatha LeBlanc To: Cathryn Moffett Subject: Manitouwadge group - letter of support Date: March 17, 2021 11:34:41 AM Attachments: <email address removed> Here is a copy of correspondence with Manitouwadge From: [email protected] <email address removed> Sent: October 28, 2020 11:00 AM To: Tabatha LeBlanc <email address removed> Cc: Owen Cranney <email address removed> ; Joleen Keough <email address removed> Subject: RE: PGM Hi Tabatha, This email is to confirm that the Township would be happy to host Generation Mining via Zoom for a 15 minute presentation to Council at 7:00 pm on Wednesday, November 11, 2020. The format will be 15 min for presentation and 10 min for Q&A. Can you please forward your presentation no later than Wednesday, November 4th to circulate to Council with their Agenda package. We will also promote the presentation online for members of the public to watch the live stream of the video through our YouTube channel. Member of the public may have questions or comments on the project so we will need to ensure that they know how and who to contact at Generation Mining. Please advise the names and positions of anyone from Generation Mining who will be present for the presentation. Please log in to the Zoom link a few minutes before 7 pm. You will be placed in a “waiting room” and staff will admit you prior to the meeting start time at 7:00 pm. Let me know if you have any questions. Thanks, Florence The Zoom meeting link is attached below: Township of Manitouwadge is inviting you to a scheduled Zoom meeting. -

Community Profiles for the Oneca Education And

FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 Political/Territorial Facts About This Community Phone Number First Nation and Address Nation and Region Organization or and Fax Number Affiliation (if any) • Census data from 2006 states Aamjiwnaang First that there are 706 residents. Nation • This is a Chippewa (Ojibwe) community located on the (Sarnia) (519) 336‐8410 Anishinabek Nation shores of the St. Clair River near SFNS Sarnia, Ontario. 978 Tashmoo Avenue (Fax) 336‐0382 • There are 253 private dwellings in this community. SARNIA, Ontario (Southwest Region) • The land base is 12.57 square kilometres. N7T 7H5 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 506 residents. Alderville First Nation • This community is located in South‐Central Ontario. It is 11696 Second Line (905) 352‐2011 Anishinabek Nation intersected by County Road 45, and is located on the south side P.O. Box 46 (Fax) 352‐3242 Ogemawahj of Rice Lake and is 30km north of Cobourg. ROSENEATH, Ontario (Southeast Region) • There are 237 private dwellings in this community. K0K 2X0 • The land base is 12.52 square kilometres. COPYRIGHT OF THE ONECA EDUCATION PARTNERSHIPS PROGRAM 1 FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 406 residents. • This Algonquin community Algonquins of called Pikwàkanagàn is situated Pikwakanagan First on the beautiful shores of the Nation (613) 625‐2800 Bonnechere River and Golden Anishinabek Nation Lake. It is located off of Highway P.O. Box 100 (Fax) 625‐1149 N/A 60 and is 1 1/2 hours west of Ottawa and 1 1/2 hours south of GOLDEN LAKE, Ontario Algonquin Park. -

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: an Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: An Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents Superior-Greenstone District School Board 2014 2 Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region Acknowledgements Superior-Greenstone District School Board David Tamblyn, Director of Education Nancy Petrick, Superintendent of Education Barb Willcocks, Aboriginal Education Student Success Lead The Native Education Advisory Committee Rachel A. Mishenene Consulting Curriculum Developer ~ Rachel Mishenene, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Edited by Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student and M.Ed. I would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their contribution in the development of this resource. Miigwetch. Dr. Cyndy Baskin, Ph.D. Heather Cameron, M.A. Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Martha Moon, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Brian Tucker and Cameron Burgess, The Métis Nation of Ontario Deb St. Amant, B.Ed., B.A. Photo Credits Ruthless Images © All photos (with the exception of two) were taken in the First Nations communities of the Superior-Greenstone region. Additional images that are referenced at the end of the book. © Copyright 2014 Superior-Greenstone District School Board All correspondence and inquiries should be directed to: Superior-Greenstone District School Board Office 12 Hemlo Drive, Postal Bag ‘A’, Marathon, ON P0T 2E0 Telephone: 807.229.0436 / Facsimile: 807.229.1471 / Webpage: www.sgdsb.on.ca Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region 3 Contents What’s Inside? Page Indian Power by Judy Wawia 6 About the Handbook 7 -

Anishinabek-PS-Annual-Report-2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ANISHINABEK POLICE SERVICE Oo’deh’nah’wi…nongohm, waabung, maamawi! (Community…today, tomorrow, together!) TABLE OF CONTENTS Mission Statement 4 Organizational Charts 5 Map of APS Detachments 7 Chairperson Report 8 Chief of Police Report 9 Inspector Reports - North, Central, South 11 Major Crime - Investigative Support Unit 21 Recruitment 22 Professional Standards 23 Corporate Services 24 Financial 25 Financial Statements 26 Human Resources 29 Use of Force 31 Statistics 32 Information Technology 34 Training & Equipment 35 MISSION STATEMENT APS provides effective, efficient, proud, trustworthy and accountable service to ensure Anishinabek residents and visitors are safe and healthy while respecting traditional cultural values including the protection of inherent rights and freedoms on our traditional territory. VISION STATEMENT Safe and healthy Anishinabek communities. GOALS Foster healthy, safe and strong communities. Provide a strong, healthy, effective, efficient, proud and accountable organization. Clarify APS roles and responsibilities regarding First Nation jurisdiction for law enforcement. 4 APS ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE - BOARD STRUCTURE ANISHINABEK POLICE SERVICE POLICE COUNCIL POLICE GOVERNING AUTHORITY POLICE GOVERNING Garden River First Nation AUTHORITY COMMITEES Curve Lake First Nation Sagamok Anishnawbek First Nation Discipline Commitee Fort William First Nation Operations Commitee POLICE CHIEF Biigtigong Nishnaabeg Finance Commitee Netmizaaggaming Nishnaabeg Cultural Commitee Biinjitiwaabik Zaaging Anishinaabek -

Aroland First Nation

Ginoogaming First Nation Community Profile Road X Road – Winter X Air X Boat X Ginoogaming First Nation is located on the northeast shore of Long Lake, 1 km south of the town of Long Lac, with access through the town from Highway 11 Ginoogaming First Nation occupies an area of 70 sq. km or 26 sq. miles (17,280 acres). Ginoogaming First Nation Community Profile PTO: Nishnawbe-Aski Nation TC: Matawa First Nations Management Population: 718 On Reserve: 160 Off Reserve: 616 CONTACT INFORMATION Ginoogaming First Nation LANGUAGES P.O. Box 89 Longlac, ON P0T 2A0 Linguistic Affiliation: Ojibway / Oji-Cree Phone: 807-876-2249 Mother Tongue: English Toll Free: 1-888-570-8942 Fax: 807-876-2495 Traditional languages of Ojibway and Oji-Cree are spoken. Many young people are not fluent in their OVERVIEW language and English is most commonly used. GOVERNANCE Election System YES NO Electoral X Custom X Term of office: 2 years ELECTORAL RIDINGS (F) Thunder Bay - Superior North (P) Thunder Bay - Superior North CHIEF & COUNCIL ACCESSIBILITY TITLE Chief Accessible by YES NO Councilors 1 Ginoogaming First Nation Community Profile Councilors Transportation X Councilors Councilors Councilors Councilors Community Band Office Staff Recreation YES NO COMMENTS Facilities Phone: 807-876-2249 or 876-2242 Outdoor rink Toll Free: 1-888-570-8942 Real ice – Fax: 807-876-2495 Arena X needs improvement- TITLE TEL not useable Finance Department Calls to all Band Needs Bingo Manager Office staff are Community Hall X improvement Welfare Administrator referred through Playground -

April 26, 2021 Sent by Email Debra Sikora, Panel Chair Joint Review

Ministry of Energy, Northern Development and Mines Ministère de l’Énergie, du Développement du Nord et des Mines April 26, 2021 Sent by email Debra Sikora, Panel Chair Joint Review Panel Marathon Palladium Project [email protected] Subject: Updated Crown list for consultation and information Dear Ms. Sikora: The Impact Assessment Agency’s (the Agency) Crown Consultation Operations Division (CCOD) would like to acknowledge receipt of the April 20, 2021 letter from the Joint Review Panel (the Panel) for the proposed Marathon Palladium Project (the Project). In this letter, the Panel has invited the CCOD to review the technical merit of the information contained in the Generation PGM Inc. Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) Addendum and supporting documents, as measured against the EIS Guidelines, related to the CCOD’s mandate and expertise. We would like to thank you for this opportunity to participate in the process. The Agency and Ontario’s consultation team (Crown consultation team), on behalf of the whole of government, are coordinating consultation activities, to the extent possible, to make best use of the environmental assessment process for the proposed Project and in order to assist the Crown in fulfilling its duty to consult with Indigenous peoples. In addition to the information received from Indigenous groups through consultation activities, the Crown consultation team will rely on the information collected by the Panel for the purpose of the environmental assessment in order to inform the Crown’s assessment of potential adverse impacts of the proposed Project on the potential or established Aboriginal or Treaty Rights. The Crown consultation team, on behalf of the whole of government, will also use the Agency’s Guidance: Assessment of Potential Impacts on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to inform its assessment. -

Ginoogaming First Nation Social Impact Assessment

` Ginoogaming First Nation Social Impact Assessment June 29, 2015 Submitted by Ginoogaming First Nation Social Impact Assessment ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A hearty ‘Migwach’ is needed for all those community members who participated in the engagement sessions with such enthusiasm and openness. Thus project could not have been completed without you, and your input is shown in the richness of the reports and annexes. Acknowledgement is also due for Chief and Council who on occasions went out of their way to meet for extended periods outside of regular hours, to ensure that input and guidance was available. No acknowledgements would be complete without highlighting the incredible assistance and talent of the GFN staff: Conrad Chapais who initiated the assessments, Erin Smythington- Armstrong who worked tirelessly to ensure the process ran smoothly, Calvin Taylor who helped guide the engagement, and Priscila Fisher and Marianna Echum, who were always available to assist, and even ran stations at the Open House on short notice. Also, a thank you is extended to Miller Dickson Blaise and Cornerstone Consulting, who worked in partnership with Beringia in many of the engagement sessions. Thank you to Jeff Cook and Glen Hearns from Beringia Community Planning. i June 29, 2015 June Ginoogaming First Nation Social Impact Assessment EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background Ginoogaming First Nation (GFN) is facing new resource development projects in its traditional territories, with the potential for significant impacts on the Nation and their land. The anticipated impacts could be positive in terms of increased jobs and economic development. However, there is also the risk of negative impacts such as environmental degradation, increased social and health problems associated with substance abuse, and continued erosion of traditional values. -

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE A WIN FOR MATAWA FIRST NATIONS CANADA AND CLIFFS LOSE DECISION ON MOTIONS IN LEGAL PROCEEDING Chiefs Reiterate Their Demand For An Immediate Halt to the Current Environmental Assessment Process THUNDER BAY, ON. MARCH 19, 2013. ‐ Matawa First Nations Chiefs welcome the decision by Madam Prothonotary Aronovitch of the Federal Court to deny motions filed by Canada and Cliffs in the Judicial Review (JR) proceeding that is examining the Environmental Assessment (EA) process in the Ring of Fire. The First Nations launched a legal challenge to the federal EA process for the Cliffs Chromite Project in early November 2011. Cliffs and Canada brought motions challenging some of the evidence of the First Nations in the case. On Friday March 15, 2013, Cliffs and Canada lost their motions on all counts. The Federal Court found that these motions caused "unnecessarily delay" in the proceeding. The court awarded costs to the First Nations, and set the case on an expedited schedule towards a hearing. “Cliffs needs to halt the current EA process and negotiate an appropriate process with our First Nations. We believe the Court will agree with us on that too.” said Chief Roger Wesley of Constance Lake First Nation. “What we have now is a paper-based EA process, run completely outside of the communities affected, with no meaningful involvement of First Nations, and is non-transparent. It needs to be made accessible, by holding hearings in the First Nations and using an independent panel. The First Nations have made it very clear that they are willing to negotiate the parameters for an effective EA process,” said Chief Sonny Gagnon of Aroland First Nation. -

For a List of All Advisors Please Click Here

Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries Ministry for Seniors and Accessibility Regional Services and Corporate Support Branch – Contact List Region and Office Staff Member Program Delivery Area Central Region Laura Lee Dam Not Applicable Toronto Office Manager 400 University Avenue, 2nd Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2R9 Email: [email protected] Phone: (519) 741-7785 Central Region Roya Gabriele Not Applicable Toronto Office Regional Coordinator 400 University Avenue, 2nd Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2R9 Email: [email protected] Phone: (647) 631-8951 Central Region Sherry Gupta Not Applicable Toronto Office Public Affairs and Program 400 University Avenue, 2nd Coordinator Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2R9 Email: [email protected] Phone: (647) 620-6348 Central Region Irina Khvashchevskaya Toronto West (west of Bathurst Street, north to Steeles Toronto Office Regional Development Advisor Avenue) and Etobicoke 400 University Avenue, 2nd Sport/Recreation, Culture/Heritage, Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2R9 Seniors and Accessibility Portfolios Email: [email protected] Phone: (647) 629-4498 Central Region, Bilingual Mohamed Bekkal Toronto East (east of Don Valley Parkway, north to Steeles Toronto Office Regional Development Advisor Avenue) and Scarborough 400 University Avenue, 2nd Sport/Recreation, Culture/Heritage, Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2R9 Seniors and Accessibility Portfolios Francophone Organizations in Toronto Email: [email protected] Phone: (416) 509-5461 Central Region Shannon Todd -

Understanding Our Food Systems SEPTEMBER - DECEMBER 2019

Understanding Our Food Systems SEPTEMBER - DECEMBER 2019 CREATING AND FOSTERING INDIGENOUS FOOD SOVEREIGNTY IN NORTHWESTERN ONTARIO This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health & Long-Term Care Acknowledgements The work and success of this project would not have been possible without the following individuals and organizations: FIRST NATION COMMUNITIES AND THEIR RESPECTIVE ORGANIZATIONS STAFF AND COMMUNITY MEMBERS: • Roots to Harvest • Animbiigoo Zaagi’igan Anishinaabek • Sustainable Food Systems Lab and Lakehead University • Aroland First Nation • Thunder Bay and Area Food Strategy • Biigtigong Nishnaabeg • EcoSuperior Thunder Bay • Biinjitiwaabik Zaaging Anishinaabek • Ingaged Creative Productions • Bingwi Neyaashi Anishinaabek • Thunder Bay Indigenous Friendship Centre • Fort William First Nation • Ka-Na-Chi-Hih Specialized Solvent Abuse Treatment Centre • Ginoogaming First Nation • Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek • Long Lake #58 First Nation OTHER SUPPORTING INDIVIDUALS • Namaygoosisagagun • Netmizaaggamig Nishnaabeg • Dr. Nancy Sandy • Rachel Portinga • Pawgwasheeng • Katie Akey • Michaela Bohunicky • Red Rock Indian Band • Rick Leblanc • Volker Kromm • Whitesand First Nation • Lee Sieswerda • Shannon Costigan • Rich Francis • Katie Berube PROJECT TEAM MEMBERS • Rachel Globensky • Dianne Cataldo • Jessica Mclaughlin • Jeordi Pierre • Margot Ross • Dr. Charles Levkoe • Vince Simon • Sharon Dempsey • Ivan Ho • Sarah Simon • Erin Beagle • Shelby Gagnon • Allan Bonazzo • Dr. Joseph Leblanc • Tyler Waboose • Kathy Loon • Norm Lamke • Brad Bannon • Brenda Marshall • James Yerxa • Beau Boucher • Hayley Lapalme • Courtney Strutt • Dorothy Rody • Victoria Pullia • Lynda Roberts • Karen Kerk • Dr. Janet DeMille • Silva Sawula • Charlene Baglien • Roseanna Hudson RESPECTED ELDERS • Tom Kane • Gene Nowegejick • Marcel Bananish • Marlene Tsun • Gerry Martin • Larry McDermott • William Yerxa • Florence Yerxa TO CITE THIS REPORT: McLaughlin, J., Levkoe, C.Z., and Ho, I. -

Appendix 18-I: Socio-Economic Data Tables by Community

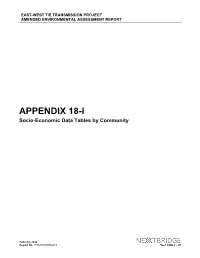

EAST-WEST TIE TRANSMISSION PROJECT AMENDED ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT REPORT APPENDIX 18-I Socio-Economic Data Tables by Community February 2018 Report No. 1536607/2000/2219 APPENDIX 18-I SOCIO-ECONOMIC DATA TABLES BY COMMUNITY LIST OF TABLES Table 18-I-1: Population ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Table 18-I-2: Labour Force Activity ...................................................................................................................... 2 Table 18-I-3: Employment by Sector, 2011 ......................................................................................................... 3 Table 18-I-4: Incomes and Earnings, 2011 .......................................................................................................... 5 Table 18-I-5: Educational Attainment, 2011 ........................................................................................................ 6 February 2018 Project No. 1536607/2000/2219 I APPENDIX 18-I SOCIO-ECONOMIC DATA TABLES BY COMMUNITY Table 18-I-1: Population Population 2001 2006 2011 % Change 2001–2011 City of Thunder Bay 109,016 109,140 108,359 -0.6 Municipality of Wawa 3,668 3,204 2,975 -18.9 Town of Marathon 4,416 3,863 3,353 -24.1 Township of Dorion 442 379 338 -23.5 Township of Nipigon 1,964 1,752 1,631 -17.0 Township of Red Rock 1,233 1,063 942 -23.6 Township of Schreiber 1,448 901 1,126 -22.2 Municipality of Shuniah 2,466 2,913 2,737 11.0 Township of Terrace Bay 1,950 -

Escribe Agenda Package

THUNDER BAY DISTRICT HEALTH UNIT BOARD OF HEALTH MEETING AGENDA 2020-11 November 18, 2020 1:00 PM Microsoft Teams Meeting Pages 1. CALL TO ORDER Chair: Mr. James McPherson 2. ATTENDANCE AND ANNOUNCEMENTS 3. DECLARATIONS OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST 4. AGENDA APPROVAL RES 1: THAT the Agenda for the Regular Board of Health Meeting to be held on November 18, 2020, be approved. 5. INFORMATION SESSION 1 6. MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS MEETINGS 6.1. Thunder Bay District Board of Health 7 The Minutes of the Thunder Bay District Board of Health (Regular and Closed Session) Meeting held on October 21, 2020, for approval. RES 2: THAT the Minutes of the Thunder Bay District Board of Health (Regular and Closed Session) Meeting held on October 21, 2020, be approved 7. MATTERS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES 8. BOARD OF HEALTH (CLOSED SESSION) MEETING RES 3a: THAT the Board of Health move into Closed Session to receive information relative to labour relations or employee negotiations. 9. DECISIONS OF THE BOARD 9.1. 2021 Mandatory Program Budgets 16 Report No. 37-2020 (Finance) relative to providing the Board of Health with the proposed 2021 Mandatory Program (Cost-Shared) Budgets. RES 4: THAT with respect to Report No. 37 – 2020 (Finance), we recommend that the: 1. 2021 Mandatory Core Program Budget (Cost-Shared) be approved at $15,724,603 including 40 net full time equivalent (FTE) positions, for submission to the Ministry of Health; 1. Municipal Levy be set at $3,213,543; 1. 100% Indigenous Communities: Indigenous Partnerships budget be approved at $99,500, with 1.0 FTE and submitted to the Ministry of Health; 1.