Handle with Care: a Pedagogical Theory of Touch in Teaching Dance Technique Based on Four Case Studies a Dissertation Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

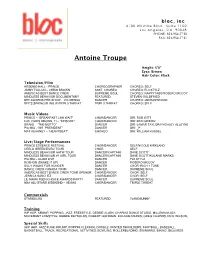

Antoine Troupe

bloc, inc. 6100 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90048 PHONE: 323-954-7730 FAX: 323-954-7731 Antoine Troupe Height: 5’8” Eyes: Brown Hair Color: Black Television/Film ARSENIO HALL - PRINCE CHOREOGRAPHER CHOREO: SELF JIMMY FALLON – CHRIS BROWN ASST. CHOREO CHOREO: FLII STYLZ AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW SUPREME SOUL CHOREO: NAPPYTABS/ROSERO MCCOY MINDLESS BEHAVIOR DOCUMENTARY FEATURED STEVEN GOLDFRIED BET AWARDS PRE-SHOW – VIC MENSA DANCER CHOREO: IAN EASTWOOD BET’S SPRING BLING W/TRIPL3 THREAT TRIPL3 THREAT CHOREO: SELF Music Videos PRINCE – “BREAKFAST CAN WAIT” CHOR/DANCER DIR: ROB WITT E40, CHRIS BROWN, TI – “EPISODE” CHOR/DANCER DIR: BEN GRIFFIN DRAKE – “THE MOTTO” DANCER DIR: LAMAR TAYLOR/HYGHLEY ALLEYNE PIA MIA - “MR. PRESIDENT” DANCER DIR: _P MAT KEARNEY – “HEARTBEAT” CHOREO DIR: WILLIAM RUSSEL Live/Stage Performances PRINCE ESSENCE FESTIVAL CHOR/DANCER SELF/NICOLE KIRKLAND CEELO GREEN EURO TOUR CHOR SELF MINDLESS BEHAVIOR AATW TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT MINDLESS BEHAVIOR #1 GIRL TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT/KOLANIE MARKS PIA MIA – GUAM LIVE DANCER FLII STYLZ ROSHON (SHAKE IT UP) DANCER ROSERO MCCOY SILLY WALKS FOR HUNGER DANCER CHOR: RICH + TONE DANCE CREW CANADA TOUR DANCER SUPREME SOUL AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW TOUR OPENER CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF JESSICA SANCHEZ CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF LIL MAMA TEEN CHOICE AWARDS PARTY DANCER SUPREME SOUL NBA ALL-STARS WEEKEND – VEGAS CHOR/DANCER TRIPLE THREAT Commercials STARBUCKS FEATURED 72ANDSUNNY Training HIP HOP, KRUMP, POPPING, JAZZ, FREESTYLE, DEBBIE ALLEN, CHAPKIS DANCE STUDIO, MILLENIUM, IDA, MOVEMENT LIFESTYLE, DEBBIE REYNOLDS, ROBERT HOFFMAN, KOLANIE MARKS, GREG CHAPKIS, NICK WILSON, Special Skills (HIP HOP, JAZZ FUNK, KRUMP, POPPIN, FLEXING), DOUBLE JOINTED SHOULDERS, FOOTBALL, BASEBALL, BASKETBALL, TRACK, RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES, BOWLING, ROLLERBLADING, SWIMMING, BIKING, BILLIARDS . -

Wedding Ringer -FULL SCRIPT W GREEN REVISIONS.Pdf

THE WEDDING RINGER FKA BEST MAN, Inc. / THE GOLDEN TUX by Jeremy Garelick & Jay Lavender GREEN REVISED - 10.22.13 YELLOW REVISED - 10.11.13 PINK REVISED - 10.1.13 BLUE REVISED - 9.17.13 WHITE SHOOTING SCRIPT - 8.27.13 Screen Gems Productions, Inc. 10202 W. Washington Blvd. Stage 6 Suite 4100 Culver City, CA 90232 GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 1 OVER BLACK A DIAL TONE...numbers DIALED...phone RINGING. SETH (V.O.) Hello? DOUG (V.O.) Oh hi, uh, Seth? SETH (V.O.) Yeah? DOUG (V.O.) It’s Doug. SETH (V.O.) Doug? Doug who? OPEN TIGHT ON DOUG Doug Harris... 30ish, on the slightly dweebier side of average. 1 REVEAL: INT. DOUG’S OFFICE - DAY 1 Organized clutter, stacks of paper cover the desk. Vintage posters/jerseys of Los Angeles sports legends adorn the walls- -ERIC DICKERSON, JIM PLUNKETT, KURT RAMBIS, STEVE GARVEY- DOUG You know, Doug Harris...Persian Rug Doug? SETH (OVER PHONE) Doug Harris! Of course. What’s up? DOUG (relieved) I know it’s been awhile, but I was calling because, I uh, have some good news...I’m getting married. SETH (OVER PHONE) That’s great. Congratulations. DOUG And, well, I was wondering if you might be interested in perhaps being my best man. GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 2 Dead silence. SETH (OVER PHONE) I have to be honest, Doug. This is kind of awkward. I mean, we don’t really know each other that well. DOUG Well...what about that weekend in Carlsbad Caverns? SETH (OVER PHONE) That was a ninth grade field trip, the whole class went. -

Grades Prek - 12

For Teaching and Learning in Grades PreK - 12 New York City Department of Education New York City Department of Education • Joel I. Klein, Chancellor • Marcia V. Lyles, Deputy Chancellor for Teaching and Learning • Sharon Dunn, Senior Instructional Manager for Arts Education Dance Curriculum Development Contributing Writers Dance Organization Representatives and Reviewers Planning Co-Chairs Consultants New York City Department of Education All of the contributing writers, plus: Ann Biddle, Stories in Motion Joan Finkelstein, Director of Dance Programs, Andrew Buck, Arts Supervisor, Region 8 Leslee Asch, National Dance Institute Office of the Arts and Special Projects, Tina Curran, Language of Dance Center New York City Department of Education Eileen Goldblatt, Arts Supervisor, Region 9 Mary Barnett, Consultant Martha Hart Eddy, Center for Kinesthetic Education Mary Lisa Burns, Merce Cunningham Dance Company Jody Gottfried Arnhold, Founding Director, Kyle S. Haver, Instructional Specialist in Literacy and Humanities Mark DeGarmo, Mark DeGarmo and Dancers Dance Education Laboratory of the 92nd Street Y Barbara Gurr, Director of Visual Arts, New York City Paul King, Director of Theater Programs Daniel Gwirtzman, Daniel Gwirtzman Dance Company Department of Education Tina Ramirez, Artistic Director, Ballet Hispanico Eva Pataki, Arts Supervisor, Region 3 Joanne Robinson Hill, The Joyce Theater Laura Hymers, Trisha Brown Dance Company Leslie Hunt, Center for Arts Education Arlene Jordan, New York City Center New York City Department of Education -

B-Girl Like a B-Boy Marginalization of Women in Hip-Hop Dance a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Division of the University of H

B-GIRL LIKE A B-BOY MARGINALIZATION OF WOMEN IN HIP-HOP DANCE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN DANCE DECEMBER 2014 By Jenny Sky Fung Thesis Committee: Kara Miller, Chairperson Gregg Lizenbery Judy Van Zile ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give a big thanks to Jacquelyn Chappel, Desiree Seguritan, and Jill Dahlman for contributing their time and energy in helping me to edit my thesis. I’d also like to give a big mahalo to my thesis committee: Gregg Lizenbery, Judy Van Zile, and Kara Miller for all their help, support, and patience in pushing me to complete this thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………… 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 1 2. Literature Review………………………………………………………………… 6 3. Methodology……………………………………………………………………… 20 4. 4.1. Background History…………………………………………………………. 24 4.2. Tracing Female Dancers in Literature and Film……………………………... 37 4.3. Some History and Her-story About Hip-Hop Dance “Back in the Day”......... 42 4.4. Tracing Females Dancers in New York City………………………………... 49 4.5. B-Girl Like a B-Boy: What Makes Breaking Masculine and Male Dominant?....................................................................................................... 53 4.6. Generation 2000: The B-Boys, B-Girls, and Urban Street Dancers of Today………………...……………………………………………………… 59 5. Issues Women Experience…………………………………………………….… 66 5.1 The Physical Aspect of Breaking………………………………………….… 66 5.2. Women and the Cipher……………………………………………………… 73 5.3. The Token B-Girl…………………………………………………………… 80 6.1. Tackling Marginalization………………………………………………………… 86 6.2. Acknowledging Discrimination…………………………………………….. 86 6.3. Speaking Out and Establishing Presence…………………………………… 90 6.4. Working Around a Man’s World…………………………………………… 93 6.5. -

Beijing's South China Sea Lawfare Strategy

Today’s News 15 May 2021 (Saturday) A. NAVY NEWS/COVID NEWS/PHOTOS Title Writer Newspaper Page 1 Missile boats boosting Navy capability D Tribune A3 2 Navy adapts, survives via virtual technology D Tribune B11 3 DOH rejects proposals to issue vaccine pass S Crisostomo P Star 6 B. NATIONAL HEADLINES Title Writer Newspaper Page 4 Phl to sign deal for 40M Pfizer doses J Clapano P Star 1 PNP Raps vs Red- N Semilla PDI A1 5 tagged ‘Lumad’ helpers junked C. NATIONAL SECURITY Title Writer Newspaper Page 6 Duterte won’t pul ul out PH vessels in K Calayag M Times A2 disputed sea 7 Chinese envoys says Phl, China ‘properly H Flores P Star 2 handled’ sea dispute 8 Signature drive asks Rody retract statement H Flores P Star 2 9 Only China to blame for PH loss of Panatag, C Avendano PDI A9 says ex-DFA chief 10 DU30: Opposition hot sea row but not L Salaverria PDI A2 helping vs virus 11 Duterte invites Enrile to shed light WPS M Bulletin 1 issue 12 Rody vows no Phl ship to leave WPS D Tribune 1 13 Pangilinan: WPS issue is no joking matter J Esmael M Times 1 14 Duterte won’t pull out PH vessels in disputed K Calayag M Times A1 sea 15 Ex-envoy: Stop ‘blame game’ start enforcing R Requejo M Standard A1 Hague ruling 16 Rody puts China on notice V Barcelo M Standard A1 17 ‘Roque’s WPS remarks don’t reflect PH M Standard A4 policy 18 Why Philippines is important to China E Banawis M Standard B1 19 Duterte ‘di paatrasin ang 2 barko kahit M Escudero Ngayon 2 patayin ng China 20 PDU30 sa Tsina: Barko ng Pinas ‘di ko M Escudero PM 2 iaatras, patayin mo man ako 21 Presidenteng ‘nakakapuwing’ at may pusong J Umali PM 3 David 22 WPS patrols P Tonight 4 23 Arbitral award, just a piece of paper? C Sorita P Tonight 4 24 Use of diplomacy on WPS issue urged P Tonight 10 25 ‘I won’t allow PH to join any war with US’: P Tonight 6 Duterte D. -

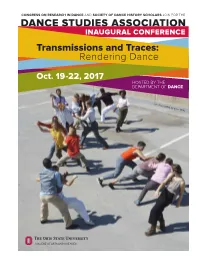

Transmissions and Traces: Rendering Dance

INAUGURAL CONFERENCE Transmissions and Traces: Rendering Dance Oct. 19-22, 2017 HOSTED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF DANCE Sel Fou! (2016) by Bebe Miller i MAKE YOUR MOVE GET YOUR MFA IN DANCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN We encourage deep engagement through the transformative experiences of dancing and dance making. Hone your creative voice and benefit from an extraordinary breadth of resources at a leading research university. Two-year MFA includes full tuition coverage, health insurance, and stipend. smtd.umich.edu/dance CORD program 2017.indd 1 ii 7/27/17 1:33 PM DEPARTMENT OF DANCE dance.osu.edu | (614) 292-7977 | NASD Accredited Congratulations CORD+SDHS on the merger into DSA PhD in Dance Studies MFA in Dance Emerging scholars motivated to Dance artists eager to commit to a study critical theory, history, and rigorous three-year program literature in dance THINKING BODIES / AGILE MINDS PhD, MFA, BFA, Minor Faculty Movement Practice, Performance, Improvisation Susan Hadley, Chair • Harmony Bench • Ann Sofie Choreography, Dance Film, Creative Technologies Clemmensen • Dave Covey • Melanye White Dixon Pedagogy, Movement Analysis Karen Eliot • Hannah Kosstrin • Crystal Michelle History, Theory, Literature Perkins • Susan Van Pelt Petry • Daniel Roberts Music, Production, Lighting Mitchell Rose • Eddie Taketa • Valarie Williams Norah Zuniga Shaw Application Deadline: November 15, 2017 iii DANCE STUDIES ASSOCIATION Thank You Dance Studies Association (DSA) We thank Hughes, Hubbard & Reed LLP would like to thank Volunteer for the professional and generous legal Lawyers for the Arts (NY) for the support they contributed to the merger of important services they provide to the Congress on Research in Dance and the artists and arts organizations. -

Apollo Theater Presents Breakin' Convention Festival In

Apollo Theater Presents The Critically Acclaimed Global Hip-Hop Dance Theatre Festival Breakin’ Convention Festival In Collaboration with London’s Sadler’s Wells Theatre Headline programming includes groundbreaking works from internationally renowned dance crews, a special performance by popping icon Popin’ Pete, and appearance by Hip-Hop Legend and Co-Host Biz Markie Festival Expands to Week-long Celebration to Include: Artist Talks, Workshops, Dance Master Class with Jon Boogz and Lil Buck, a Unique Art Exhibition Created by Internationally Celebrated Sculptor/Painter Carlos “Mare139” Rodriguez, and Much More October 20 – 28, 2017 (Harlem, NY – October 12, 2017) – The Apollo Theater presents the return of London’s Sadler’s Wells’ critically acclaimed international hip-hop dance theatre festival—Breakin’ Convention, one of the world’s greatest celebrations of hip-hop culture. The festival, a collaboration with London’s Sadler’s Wells and now in its third year at the Apollo, provides a platform for the Theater to celebrate its hip-hop legacy and to highlight the global impact of contemporary hip-hop culture through both mainstream and experimental dance. This year’s festival will directly address several pressing issues that are part of America’s current sociopolitical landscape through performances and accompanying events, with highlights including an artist talk with dancers Jon Boogz and Lil Buck centered on dance as a tool for social justice and prison reform. Curated and hosted by nationally recognized U.K. hip-hop emcee and theater pioneer Jonzi D, Breakin’ Convention will take over the entire Apollo building and will include performances by world renowned dance companies and local crews. -

Technical, Artistic, and Pedagogical Analysis of Mark Morris' L'allegro, Il Penseroso Ed Il Moderato Mireille Radwan Dana University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 Technical, Artistic, and Pedagogical Analysis of Mark Morris' L'Allegro, Il Penseroso ed Il Moderato Mireille Radwan Dana University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Radwan Dana, Mireille, "Technical, Artistic, and Pedagogical Analysis of Mark Morris' L'Allegro, Il Penseroso ed Il Moderato" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1433. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1433 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TECHNICAL, ARTISTIC, AND PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MARK MORRIS’ L’ALLEGRO, IL PENSEROSO ED IL MODERATO by Mireille Radwan Dana A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Dance at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2017 ABSTRACT TECHNICAL, ARTISTIC, AND PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MARK MORRIS’ L’ALLEGRO, IL PENSEROSO ED IL MODERATO by Mireille Radwan Dana The University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Marcia R. Parsons Abstract This thesis analyzes Mark Morris' choreography for pedagogical purposes. It explores Morris' technique and style by investigating one of his most acclaimed works: L'Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato. Because this evening length piece offers a large selection of sections, a total of thirty-two, it provides many possibilities to investigate Morris' musicality, creative process, and style. -

Street Dance Fact File

Street Dance Fact File What is Street Dance? Key Facts Street dance is an umbrella term for various dance styles that originally • Street dance styles can be improvisational and social in nature, encouraging evolved outside of dance studios in spaces such as streets, parks, interaction and contact with other dancers and spectators and in direct playgrounds, and nightclubs and which form part of hip hop culture. relation to the rhythms and styles of the music. Street dance’s earliest styles were created largely by African Americans • There is normally a ‘battle’ element central to the dance styles – competitive and later Latinos, include breaking, which was created in The Bronx, New one-upmanship which can be informal or formalised competition. York in the 1970s, whilst popping and locking originated on the West Coast during the same decade. Several other subsequent styles fall under • Still relatively young as a dance style, street dance has heavily influenced the street dance umbrella including house, hip hop, krump, turfing and popular culture and can be seen on music videos and commercials. flexing. In London, breaking, popping and locking are dominant styles. • The UK has developed a vibrant hip-hop and street dance scene with many regular battles and events. What Is Happening in Street Dance Today? Successful hip hop theatre companies include: • ZooNation, who presented the award-winning ‘Into the Hoods’ in the West End. • Boy Blue Entertainment, who won an Olivier Award for ‘Pied Piper’ and ‘Avant Garde Dance.’ • Breakin’ Convention, an annual hip-hop dance theatre festival at Sadler’s Wells in London. -

Hip Hop Dance Unit Vocabulary

Hip Hop Dance Unit Vocabulary Battles: any level of competition where break dancers, in an open space (typically a circle) participate in quick-paced, turn based routines, whether improvised or planned. Participants vary in number and can often include "crews" or teams. Winners are determined by who exhibits the most proficient combination of moves Break Dance: (b-boying/b-girling) is a combination of funk, martial arts, gymnastics. Break dancing is done to the "break" section of the music where percussion is the strongest. Freeze: (aka Stall)-stationary power move which focuses on a pose. Most skillful freezes require suspension off the floor using specific parts of the body. Two most popular are "chair freeze" and "baby freeze Flare: common floor element when spinning on hands, legs flare up and open as spin continues. Kip up: spring like action which initiates on your back, hips roll back towards head, then body springs forward and hips lift to end standing up. Krumping: Created on streets, aggressive style of hip hop that looks like fighting, a lot of hand gestures/pushing chest out/stomping feet, and was created as a way to express yourself. Locking: sharp transition between each of multiple freezes/poses like clicks associated with door bolts. Has the effect like locking the joints (moves called skeeters/Scooby doos/stop n'go/fancies) Popping: movement with elements of mime made by flexing the muscles and joints to the beat of the music. Done with locking to create movement/stop effect. Robot: precise, isolated movements and turns that lock into place before the next movement begins. -

Dispatches from the Straight Outta Fresno Archive by the Valley Public History Initiative: Preserving Our Stories Table of Contents

Dispatches from the archives Dispatches from the Straight Outta Fresno Archive By The Valley Public History Initiative: Preserving our Stories Table Of Contents Introduction This book belongs to the authors and the public Romeo Guzmán and Sean Slusser history project Straight Outta Fresno: From Popping to B-boying and B-girling. As a courtesy do not reproduce without the consent of both. Womb Geography Monique Quintana historiapublica On the Front Porch: Deborah McCoy and Fresno Streetdance FresnoStatePublicHistory Naomi M. Bragin Straight_Outta_Fresno_VPH Defying Gravity, Breakin’ Boundaries: Tropicsofmeta.com The Rise of Fresno’s Climax Crew Sean Slusser The book and project was made possible by funding from the President’s Commission on Human Relations and Equity, College of Social Sciences, the History Department, Sociology Department, the Cross Cultural UNDERGRADUATE and Gender Center, and a Humanities for All grant STUDENT ESSAYS from California Humanities, a partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Visit www.calhum.org A Blaxican’s Journey through Fresno’s Racial Landscape Raymond A. Rey It Started Here: Jean Vang’s Hip-Hop Journey Roger Espinosa INTRODUCTION Geography is central to hip-hop culture. Academics and artists alike have referenced the importance of physical spaces like “the block”; “the streets”; or “the hood” as incubators for hip-hop culture. It is in these intimate spaces that working class youth of color sift through the rubble of post- industrial neglect and repurpose it into new forms of visual art, music, and dance. Nearly fifty years after hip-hop’s emergence into the public imagination, these narratives of place have been mapped onto a distinct hip-hop cartography fixated on nostalgic references to “the Bronx”; “Compton”; and “Oakland.” Cities like Fresno are rarely included in this hip-hop cartography largely because they exist outside of institutional networks like university archives, cultural philanthropy, and the music industry. -

Dance History Timeline

Dance History Timeline By Erin Rivers Prehistoric Times Dance Style - Very easy to do and did not contain a lot of complex movements; arms were a huge factor and dances were used to represent many different everyday life aspects such as hunting, survival, marriage, death, ect. - “In harmony” and “out of harmony” dances were used to bring everyone together. New Forms/Elements & Description of Dance at this Time - Circle dance is the oldest formation in dance. Lines were very common as well. - Elements such as sticks, bones and handmade sounds were present during these times. - Dance was not always written down, but what was is still used in some elements of dance today. Influential People or Events & Specific New Developments - The Gods and Shaman were the main people and influential leaders/powers who led and inspired the dances. They were most important because they kept the community protected and safe from anything else while dancing which made them capable of becoming “one with the dance” and dancing freely and spiritually. Middle Ages & Ancient Times Styles/Types of Dance - The types and styles of dance were becoming more complex and dances now focused on the mind with natural and pronounced movements. New Forms/Elements & Description of Dance at this Time - To be able to dance, the dancers needed to be able to keep up with the music, remember the steps and have a sense of space. - Musical dance was becoming known. - Circle dance was still being used for performing Hymns. - Dance dramas were becoming popular. - Court dances were being introduced. Influential People or Events & Specific New Developments - The Queen was a big factor in dancing.