The Dance Impermanence: an Artistic Inquiry Through Improvisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

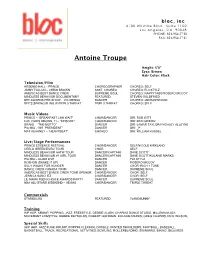

Antoine Troupe

bloc, inc. 6100 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90048 PHONE: 323-954-7730 FAX: 323-954-7731 Antoine Troupe Height: 5’8” Eyes: Brown Hair Color: Black Television/Film ARSENIO HALL - PRINCE CHOREOGRAPHER CHOREO: SELF JIMMY FALLON – CHRIS BROWN ASST. CHOREO CHOREO: FLII STYLZ AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW SUPREME SOUL CHOREO: NAPPYTABS/ROSERO MCCOY MINDLESS BEHAVIOR DOCUMENTARY FEATURED STEVEN GOLDFRIED BET AWARDS PRE-SHOW – VIC MENSA DANCER CHOREO: IAN EASTWOOD BET’S SPRING BLING W/TRIPL3 THREAT TRIPL3 THREAT CHOREO: SELF Music Videos PRINCE – “BREAKFAST CAN WAIT” CHOR/DANCER DIR: ROB WITT E40, CHRIS BROWN, TI – “EPISODE” CHOR/DANCER DIR: BEN GRIFFIN DRAKE – “THE MOTTO” DANCER DIR: LAMAR TAYLOR/HYGHLEY ALLEYNE PIA MIA - “MR. PRESIDENT” DANCER DIR: _P MAT KEARNEY – “HEARTBEAT” CHOREO DIR: WILLIAM RUSSEL Live/Stage Performances PRINCE ESSENCE FESTIVAL CHOR/DANCER SELF/NICOLE KIRKLAND CEELO GREEN EURO TOUR CHOR SELF MINDLESS BEHAVIOR AATW TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT MINDLESS BEHAVIOR #1 GIRL TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT/KOLANIE MARKS PIA MIA – GUAM LIVE DANCER FLII STYLZ ROSHON (SHAKE IT UP) DANCER ROSERO MCCOY SILLY WALKS FOR HUNGER DANCER CHOR: RICH + TONE DANCE CREW CANADA TOUR DANCER SUPREME SOUL AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW TOUR OPENER CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF JESSICA SANCHEZ CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF LIL MAMA TEEN CHOICE AWARDS PARTY DANCER SUPREME SOUL NBA ALL-STARS WEEKEND – VEGAS CHOR/DANCER TRIPLE THREAT Commercials STARBUCKS FEATURED 72ANDSUNNY Training HIP HOP, KRUMP, POPPING, JAZZ, FREESTYLE, DEBBIE ALLEN, CHAPKIS DANCE STUDIO, MILLENIUM, IDA, MOVEMENT LIFESTYLE, DEBBIE REYNOLDS, ROBERT HOFFMAN, KOLANIE MARKS, GREG CHAPKIS, NICK WILSON, Special Skills (HIP HOP, JAZZ FUNK, KRUMP, POPPIN, FLEXING), DOUBLE JOINTED SHOULDERS, FOOTBALL, BASEBALL, BASKETBALL, TRACK, RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES, BOWLING, ROLLERBLADING, SWIMMING, BIKING, BILLIARDS . -

Mindfulness and the Buddha's Noble Eightfold Path

Chapter 3 Mindfulness and the Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path Malcolm Huxter 3.1 Introduction In the late 1970s, Kabat-Zinn, an immunologist, was on a Buddhist meditation retreat practicing mindfulness meditation. Inspired by the personal benefits, he de- veloped a strong intention to share these skills with those who would not normally attend retreats or wish to practice meditation. Kabat-Zinn developed and began con- ducting mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in 1979. He defined mindful- ness as, “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment to moment” (Kabat-Zinn 2003, p. 145). Since the establishment of MBSR, thousands of individuals have reduced psychological and physical suffering by attending these programs (see www.unmassmed.edu/cfm/mbsr/). Furthermore, the research into and popularity of mindfulness and mindfulness-based programs in medical and psychological settings has grown exponentially (Kabat-Zinn 2009). Kabat-Zinn (1990) deliberately detached the language and practice of mind- fulness from its Buddhist origins so that it would be more readily acceptable in Western health settings (Kabat-Zinn 1990). Despite a lack of consensus about the finer details (Singh et al. 2008), Kabat-Zinn’s operational definition of mindfulness remains possibly the most referred to in the field. Dozens of empirically validated mindfulness-based programs have emerged in the past three decades. However, the most acknowledged approaches include: MBSR (Kabat-Zinn 1990), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Linehan 1993), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes et al. 1999), and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal et al. -

Comments on Max Müller's Interpretation of the Buddhist

COMMENTS ON MAX MÜLLER'S INTERPRETATION OF THE BUDDHIST NIRVANA BY G. R. WELBON Rochester, U.S.A. Close, analytical study of ancient Indian religious terminology is a demanding discipline today engaged in by only a few scholars 1). Compounding the impressive difficulties encountered in such investiga- tions, it will be noticed, some of the terms have become incorporated into the vocabulary of contemporary non-Indians. Sanctified by several decades of inclusion in dictionaries of the various Western European languages, they have acquired an uncritical significance which makes it all the more difficult to assess their "original" and contextual signifi- cations in the Indian thought schemata. Among the terms most bedeviling in its complexity of nuance is that of nirvdna according to Buddhist usage. Recently, the distinguished Belgian scholars, Ludo and Rosane Rocher, have expressed some of the frustrations shared by many who have tried to analyse that term: Qu'on conqoive les bouddhistes comme les antagonistes conscients de l'hin- douisme ou comme les "freres des brahmanes des Upanishads", il n'en reste pas moins que le concept bouddhiste de nirvti1la a ete construit sur ou a r6agi contre des elements de 1'hindouisme plus ancien, et qu'a son tour l'hindouisme plus recent s'est enrichi de ou a r6agi contre des elements du nirvana. Nous ne traiterons pas du Nirvana dans la presente 6tude, tout d'abord, parce que le concept hindouiste de mok,?a pose à lui seul, un tel nombre de pro- blemes qu'ils ne pourront être discutés dans leur totalite, et ensuite parce que les bouddhologues, eux-memes, n'en ont resolu les problemes fondamen- 1) Among the most distinguished must be mentioned Louis Renou and Jan Gonda. -

Wedding Ringer -FULL SCRIPT W GREEN REVISIONS.Pdf

THE WEDDING RINGER FKA BEST MAN, Inc. / THE GOLDEN TUX by Jeremy Garelick & Jay Lavender GREEN REVISED - 10.22.13 YELLOW REVISED - 10.11.13 PINK REVISED - 10.1.13 BLUE REVISED - 9.17.13 WHITE SHOOTING SCRIPT - 8.27.13 Screen Gems Productions, Inc. 10202 W. Washington Blvd. Stage 6 Suite 4100 Culver City, CA 90232 GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 1 OVER BLACK A DIAL TONE...numbers DIALED...phone RINGING. SETH (V.O.) Hello? DOUG (V.O.) Oh hi, uh, Seth? SETH (V.O.) Yeah? DOUG (V.O.) It’s Doug. SETH (V.O.) Doug? Doug who? OPEN TIGHT ON DOUG Doug Harris... 30ish, on the slightly dweebier side of average. 1 REVEAL: INT. DOUG’S OFFICE - DAY 1 Organized clutter, stacks of paper cover the desk. Vintage posters/jerseys of Los Angeles sports legends adorn the walls- -ERIC DICKERSON, JIM PLUNKETT, KURT RAMBIS, STEVE GARVEY- DOUG You know, Doug Harris...Persian Rug Doug? SETH (OVER PHONE) Doug Harris! Of course. What’s up? DOUG (relieved) I know it’s been awhile, but I was calling because, I uh, have some good news...I’m getting married. SETH (OVER PHONE) That’s great. Congratulations. DOUG And, well, I was wondering if you might be interested in perhaps being my best man. GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 2 Dead silence. SETH (OVER PHONE) I have to be honest, Doug. This is kind of awkward. I mean, we don’t really know each other that well. DOUG Well...what about that weekend in Carlsbad Caverns? SETH (OVER PHONE) That was a ninth grade field trip, the whole class went. -

Taking Refuge in the Triple Gem and the 5 Lay Vows – Geshe Tenzin Zopa

Taking Refuge in the Triple Gem and the 5 Lay Vows – Geshe Tenzin Zopa Why take Refuge? If one wishes to optimise this human life, there is much benefit to taking Refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Holding Refuge vows is crucial to those inspired to follow the path of the Buddha. Whether one becomes a child of the Buddha and under the protection of the Buddha or not, is determined at the time when one receives the blessing of Refuge from Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Even though one’s family may follow the Buddha’s path and call themselves Buddhists, if one has not taken Refuge with the full understanding of what Refuge means and involves, one is not yet a Buddhist. Firstly, we need to know that we have obtained this precious human rebirth which has the 8 freedoms and the 10 Endowments which enable us to practice the Path. The Buddha has taught us that with such a precious human rebirth, we are able to embark on the 3 higher trainings namely, morality, concentration and cultivation of wisdom realising emptiness. These are critical if we wish to eradicate samsaric suffering, including that of birth, aging and death. In order to actualise the wisdom realising emptiness, one requires realisations in concentration; in order to gain realisations in concentration, one needs to live in and gain realisations of morality. Without these 3, there can be no antidote to samsara, let alone attaining enlightenment. In relation to the practice of morality, Refuge Vows forms the basis. Refuge Vows are also the foundation of all other vows such as individual liberation / pratimoksha vows, ordination vows, bodhisattva vows, tantric vows. -

The Buddhist Six-Worlds Model of Consciousness and Reality

THE BUDDHIST SIX-WORLDS MODEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS AND REALITY Ralph Metzner Sonoma, California Historically there have been two main metaphors for consciousness, one spatial or topographical, the other temporal or biographical (Metzner, 1989). The spatial meta phor is expressed in conceptions of consciousness as like a territory, a terrain, or a field, a state one can enter into or leave, or like empty space, as in the Buddhist notion of sunyata.We could speculate that people who unconsciously adhere to a spatial conception of consciousness would tend to a certain kind of fixity of perception and worldview. The "static" aspects of experience might be in the foreground of aware ness, and there could be a craving for stability and persistence. From this point of view, ordinary waking consciousness is the preferred state, and "altered states" are viewed with some anxiety and suspicion-as if an "altered" state is automatically abnormal or pathological in some way. This is close to the attitude of mainstream Western thought toward alterations of consciousness: even the rich diversity of dreamlife and the changed awareness possible with introspection, psychotherapy, or meditation is regarded with suspicion by the dominant extraverted worldview. The temporal metaphor for consciousness on the other hand, is seen in conceptions such as William James' "stream of thought," or the stream of awareness, or the "flow experience"; as well as in developmental theories of consciousness going through various stages. Historically and cross-culturally, we see the temporal metaphor emphasized in the thought of the pre-Socratic philosophers Thales and Heraclitus, in the Buddhist teachings of impermanence (anicca), and in the Taoist emphasis on the flows and eddies of water as the basic underlying pattern of all being. -

Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Handbook Version

Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Study material for your retreat at Tiratanaloka Page 1 of 43 Edited by Vandananjyoti, Version 2:1, July 2020 Table of Contents Introduction to the Handbook Study Area 1. Centrality of Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Study Area 2. Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Study Area 3. Opening of the Dharma Eye and Stream Entry Study Area 4. Going Forth Study Area 5. The Altruistic Dimension of Going for Refuge and Joining the Order Page 2 of 43 Edited by Vandananjyoti, Version 2:1, July 2020 Introduction to the Handbook The purpose of this handbook is to give you the opportunity to look in depth at the material that we will be studying on the Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels retreat at Tiratanaloka. In this handbook we give you material to study for each area we’ll be studying on the retreat. We will also have some talks on the retreat itself where the team will bring out their own personal reflections on the topics covered. As well as the study material in this handbook, it would be helpful if you could read Sangharakshita’s book ‘The History of My Going for Refuge’. You can buy this from Windhorse Publications. There is also some optional extra study material at the beginning of each section. Some of the optional material is in the form of talks that can be downloaded from the Free Buddhist Audio website at www.freebuddhistaudio.com. These aren’t by any means exhaustive - Free Buddhist Audio is growing and changing all the time so you may find other material equally relevant! For example, at the time of writing, Vessantara has just completed a series of talks called ‘Aspects of Going for Refuge’ (2016) at Cambridge Buddhist Centre. -

Explanations of Dukkha 383

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 21 • Number 2 • 1998 PIERRE ARfcNES Herm6neutique des tantra: 6tude de quelques usages du «sens cach6» 173 GEORGES DREYFUS The Shuk-den Affair: History and Nature of a Quarrel 227 ROBERT MAYER The Figure of MaheSvara/Rudra in the rNin-ma-pa Tantric Tradition 271 JOHN NEWMAN Islam in the Kalacakra Tantra 311 MAX NIHOM Vajravinaya and VajraSaunda: A 'Ghost' Goddess and her Syncretic Spouse 373 TILMANN VETTER Explanations of dukkha 383 Index to JIABS 11-21, by Torn TOMABECHI 389 English summary of the article by P. Arenes 409 TILMANN VETTER Explanations of dukkha The present contribution presents some philological observations and a historical assumption concerning the First Noble Truth. It is well-known to most buddhologists and many Buddhists that the explanations of the First Noble Truth in the First Sermon as found in the Mahavagga of the Vinayapitaka and in some other places conclude with a remark on the five upadanakkhandha, literally: 'branches of appro priation'. This remark is commonly understood as a summary. Practically unknown is the fact that in Hermann OLDENBERG's edition of the Mahavagga1 (= Vin I) this concluding remark contains the parti cle pi, like most of the preceding explanations of dukkha. The preceding explanations are: jati pi dukkha, jara pi dukkha, vyadhi pi dukkha, maranam pi dukkham, appiyehi sampayogo dukkho, piyehi vippayogo dukkho, yam p' iccham na labhati tarn2 pi dukkham (Vin I 10.26). Wherever pi here appears it obviously has the function of coordinating examples of events or processes that cause pain (not: are pain3): birth is causing pain, as well as decay, etc.4 1. -

Introduction to Nagarjuna's Middle View of Buddhism

Introduction to Nagarjuna’s Middle View of Buddhism by Thomas Tam, Ph.D., M.P.H June 6, 2003 Asian American / Asian Research Institute The City University of New York Nagarjuna is generally recognized as the founding father of Mahajuna Buddhism. Based on his work "Mulamadhyamika Karika," the discussion will focus on the original contribution of the Buddha, and Nagarjuna's elaboration of the middle way, and the relationship between Pratityasmautpada (inter- relatedness of everything) and Sunyata (emptiness). To provide a backdrop for my discussion tonight, I will show clips from two very popular movies—indeed, they are blockbusters that captured the hearts and minds of America in the past few years. The first is from Matrix, where Keanu Reeves, a computer programmer, who was introduced to the real world when he became aware of his existence in a totally simulated construction. (Show Matrix) The second is from MIB, or Men in Black, where aliens roamed around in New York, some from out of space. The scene you’ll see involves an extraterrestrial emperor who was murdered. The interesting thing is what lies behind the emperor. It is a graphic illustration of the existence of atman, or the self, that which directs how we behave in this world. (Show MIB) We can talk more about Tommy Lee Jones or the adventures of Trinity, Neo and Morpheus, but maybe we should get back to why we are here tonight, before we get too distracted. First of all, I want to emphasize that this is not a lecture on Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhymakakarika. -

KARMA, CHARACTER, and CONSEQUENTIALISM Damien Keown

KARMA, CHARACTER, AND CONSEQUENTIALISM Damien Keown Note: This is an electronic version of an article first published in the Journal of Religious Ethics: 24 (1996): 329-350 and reproduced here by permission. Complete citation information for the final version of the paper, as published in the print edition of Journal of Religious Ethics is available on the Blackwell Synergy online delivery service, accessible via www.blackwell-synergy.com. KARMA, CHARACTER, AND CONSEQUENTIALISM Damien Keown ABSTRACT Karma is a central feature of Buddhist ethics, but the question of its classification in terms of ethical theory has so far received little attention. Granting that karma is foundational to Buddhist ethics and arguing that what is fundamental to the Buddhist understanding of karma is the saṃskāric modification of the agent, this article relates the doctrine of karma as understood in Theravāda Buddhism to Western ethical concepts and challenges the casual consensus that treats Buddhist ethics as a variety of consequentialism. The contrary argument, that Buddhist ethics is best understood in terms of virtue-mediated character transformation, is made dialectically through a critique of recent discussions of karma by Roy Perrett and Bruce Reichenbach and through an assessment of the plausibility of Philip Ivanhoe's concept of "character consequentialism." ANY SYSTEMATIC ACCOUNT OF BUDDHIST ETHICS must before long make reference to karma. Belief in karma is a constant which underlies the philosophical diversity of the many Buddhist schools, and it is one of the few basic tenets to have escaped major reinterpretation over the course of time.l There now exists a voluminous body of scholarly literature on karma, from both Hindu and Buddhist perspectives (for a bibliography, see Potter 1980), but surprisingly, in view of the frequent references to karma as an "ethical" doctrine, almost no attention has been paid to how karma is to be classified in terms of ethical theory. -

Shankara: a Hindu Revivalist Or a Crypto-Buddhist?

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Theses Department of Religious Studies 12-4-2006 Shankara: A Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist? Kencho Tenzin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Tenzin, Kencho, "Shankara: A Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses/4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHANKARA: A HINDU REVIVALIST OR A CRYPTO BUDDHIST? by KENCHO TENZIN Under The Direction of Kathryn McClymond ABSTRACT Shankara, the great Indian thinker, was known as the accurate expounder of the Upanishads. He is seen as a towering figure in the history of Indian philosophy and is credited with restoring the teachings of the Vedas to their pristine form. However, there are others who do not see such contributions from Shankara. They criticize his philosophy by calling it “crypto-Buddhism.” It is his unique philosophy of Advaita Vedanta that puts him at odds with other Hindu orthodox schools. Ironically, he is also criticized by Buddhists as a “born enemy of Buddhism” due to his relentless attacks on their tradition. This thesis, therefore, probes the question of how Shankara should best be regarded, “a Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?” To address this question, this thesis reviews the historical setting for Shakara’s work, the state of Indian philosophy as a dynamic conversation involving Hindu and Buddhist thinkers, and finally Shankara’s intellectual genealogy. -

A List of the Lists

A LIST OF THE LISTS Ones (1) Which one thing greatly helps? Diligence in wholesome states (appamādo kusalesu dhammesu). (2) Which one thing is to be cultivated? Mindfulness with regard to the body, accompanied by pleasure (kāya-gata sati sāta-sahagatā). (3) Which one thing is to be thoroughly known? Contact as a condition of the corruptions and of grasping (phasso sāsavo upādāniyo). (4) Which one thing is to be abandoned? Self-conceit (asmi-māna). Twos (1) Which two things greatly help? Mindfulness and clear awareness. (2) Which two things are to be developed? Calm and insight. (3) Which two things are to be thoroughly known? Mind and body. (4) Which two things are to be abandoned? Ignorance and craving for existence. Threes (1) Three unwholesome roots: greed, aversion and delusion. (lobho akusala-mūlaṃ, doso akusala-mūlaṃ, moho akusala-mūlaṃ). (2) Three wholesome roots: non-greed, non-aversion and non-delusion (alobho…). (3) Three kinds of wrong conduct: in body, speech and mind (kāya-duccaritaṁ, vacī-duccaritaṁ, mano-duccaritaṁ). (4) Three kinds of unwholesome thought (akusala vitakkā): of sensuality, of enmity, of cruelty (kāma-vitakko, vyāpāda-vitakko, vihiṁsa-vitakko). (5) Three kinds of wholesome thought: of renunciation (nekkhamma-vitakko), of non-enmity, of non-cruelty. (6) Three kinds of craving: sensual craving, craving for becoming, craving for extinction (kāma-taṇhā, bhava-taṇhā, vibhava-taṇhā). (7) Three more kinds of craving: craving for [the realm] of sense-desires, craving for [the realm] of form, craving for the formless [realm] (kāma-taṇhā, rūpa-taṇhā, arūpa-taṇhā). (8) Three fetters (saṁyojanāni): of personality belief, of doubt, of attachment to rites and rituals (sakkāya diṭṭhi, vicikicchā, sīlabbata-parāmāso).