Dispatches from the Straight Outta Fresno Archive by the Valley Public History Initiative: Preserving Our Stories Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internet Killed the B-Boy Star: a Study of B-Boying Through the Lens Of

Internet Killed the B-boy Star: A Study of B-boying Through the Lens of Contemporary Media Dehui Kong Senior Seminar in Dance Fall 2010 Thesis director: Professor L. Garafola © Dehui Kong 1 B-Boy Infinitives To suck until our lips turned blue the last drops of cool juice from a crumpled cup sopped with spit the first Italian Ice of summer To chase popsicle stick skiffs along the curb skimming stormwater from Woodbridge Ave to Old Post Road To be To B-boy To be boys who snuck into a garden to pluck a baseball from mud and shit To hop that old man's fence before he bust through his front door with a lame-bull limp charge and a fist the size of half a spade To be To B-boy To lace shell-toe Adidas To say Word to Kurtis Blow To laugh the afternoons someone's mama was so black when she stepped out the car B-boy… that’s what it is, that’s why when the public the oil light went on changed it to ‘break-dancing’ they were just giving a To count hairs sprouting professional name to it, but b-boy was the original name for it and whoever wants to keep it real would around our cocks To touch 1 ourselves To pick the half-smoked keep calling it b-boy. True Blues from my father's ash tray and cough the gray grit - JoJo, from Rock Steady Crew into my hands To run my tongue along the lips of a girl with crooked teeth To be To B-boy To be boys for the ten days an 8-foot gash of cardboard lasts after we dragged that cardboard seven blocks then slapped it on the cracked blacktop To spin on our hands and backs To bruise elbows wrists and hips To Bronx-Twist Jersey version beside the mid-day traffic To swipe To pop To lock freeze and drop dimes on the hot pavement – even if the girls stopped watching and the street lamps lit buzzed all night we danced like that and no one called us home - Patrick Rosal 1 The Freshest Kids , prod. -

By Patrick James Barry a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The

CONFIRMATION BIAS: STAGED STORYTELLING IN SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARINGS by Patrick James Barry A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Enoch Brater, Chair Associate Professor Martha Jones Professor Sidonie Smith Emeritus Professor James Boyd White TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 SITES OF THEATRICALITY 1 CHAPTER 2 SITES OF STORYTELLING 32 CHAPTER 3 THE TAUNTING OF AMERICA: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF ROBERT BORK 55 CHAPTER 4 POISON IN THE EAR: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF CLARENCE THOMAS 82 CHAPTER 5 THE WISE LATINA: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF SONIA SOTOMAYOR 112 CHAPTER 6 CONCLUSION: CONFIRMATION CRITIQUE 141 WORK CITED 166 ii CHAPTER 1 SITES OF THEATRICALITY The theater is a place where a nation thinks in public in front of itself. --Martin Esslin, An Anatomy of Drama (1977)1 The Supreme Court confirmation process—once a largely behind-the-scenes affair—has lately moved front-and-center onto the public stage. --Laurence Tribe, Advice and Consent (1992)2 I. In 1975 Milner Ball, then a law professor at the University of Georgia, published an article in the Stanford Law Review called “The Play’s the Thing: An Unscientific Reflection on Trials Under the Rubric of Theater.” In it, Ball argued that by looking at the actions that take place in a courtroom as a “type of theater,” we might better understand the nature of these actions and “thereby make a small contribution to an understanding of the role of law in our society.”3 At the time, Ball’s view that courtroom action had an important “theatrical quality”4 was a minority position, even a 1 Esslin, Martin. -

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Sexuality, Social Inequalities, and Sexual Vulnerability Among Low-Income Youth in the City of Ayacucho, Peru

SEXUALITY, SOCIAL INEQUALITIES, AND SEXUAL VULNERABILITY AMONG LOW-INCOME YOUTH IN THE CITY OF AYACUCHO, PERU CARMEN J. YON Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Carmen J. Yon All rights reserved ABSTRACT Sexuality, Social Inequalities, and Sexual Vulnerability among Low-Income Youth in the City of Ayacucho, Peru Carmen J. Yon This ethnographic study explores diverse ways in which sexuality and social hierarchies and inequalities interact in the lives of low-income youth who were trained as peer-educators and sexual health and rights advocates in Ayacucho, Peru. It examines three central questions: 1) How are meanings about sexuality related to social hierarchies and social prestige among these youth? 2) How do quotidian manifestations of social inequity shape vulnerability of youth to sexual abuse and sexual risks, and their sexual agency to face these situations? and 3) What are the possibilities and limitations of existent sexual rights educational programs to diminish sexual vulnerability of youth facing diverse forms of inequality, such as economic, gender, ethnic and inter-generational disparities? I analyze what may be termed as the political economy of sexual vulnerability among low-income youth, and show the concrete ways in which it operates in their everyday life. Likewise, this research studies sexuality as a domain of reproduction, resignification and critique of social inequality and social hierarchies. The context is an Andean city, which in recent decades has experienced incomplete processes of democratization, and also a greater penetration of consumerism and transnational ideas and images. -

Mexicans and World War II 45

Mexicans and World War II 45 Mexicans and World War II: Change and Continuity Matthew Lesh Third Year Undergraduate, University of Melbourne ‘They served us beer but not food [at the drive-in movie theatre]. They told us, ‘No, we don’t serve Mexicans’, World War II veteran Natividad Campos recalled, ‘I felt pretty bad because I felt I was just as American as anybody else’.1 Campos’ experience reflected that of thousands of Mexican Americans trying to belong in a world in which they were considered non-white and consequently plagued by discrimination.2 This challenge of belonging encapsulated the Mexican American wartime experience. On the home front Mexicans stood out as patriotic supporters of the war effort. They took up various jobs in war industry, migrated to America to work in agriculture, and raised money to buy war bonds. In the military, Mexican Americans excelled in various capacities, served in combat roles out of proportion to their numbers, and received more decorations for bravery than any other ethnic group.3 During the war, Mexican Americans experienced changes in treatment and an increase in opportunity. Nevertheless, discrimination continued in education, the workplace, restaurants, in public facilities, and in housing. World War II was a turning point in which Mexican Americans were invigorated to fight against this injustice following the clash of an increased sense of self-worth, created by the contribution to the war effort, and the ongoing experience of racism.4 This article investigates this turning point by exploring the experiences of Mexican Americans before, during, and after World War II. -

THE UNIVERSITY of ARIZONA PRESS Celebrating 60 Years

THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA PRESS FALL 2019 Celebrating 60 Years The University of Arizona Press is the premier publisher of academic, regional, and literary works in the state of Arizona. We disseminate ideas and knowledge of lasting value that enrich understanding, inspire curiosity, and enlighten readers. We advance the University of Arizona’s mission by connecting scholarship and creative expression to readers worldwide. CONTENTS AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES, 10 ANTHROPOLOGY, 18, 19, 21, 25, 26 ARCHAEOLOGY, 30 ARTS, 2–3 BORDER STUDIES, 9, 18, 19, 20, 29 ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY, 4–5 ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES, 24, 26, 27 ETHNOBIOLOGY, 27 HISTORY, 2–3, 9, 16, 20, 29 INDIGNEOUS STUDIES, 6, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, 25, 28 LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 28, 29 LATINX STUDIES, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15 LITERATURE, 7 POETRY, 6, 8 SOCIAL JUSTICE, 10, 13, 14, 15, 24 SPACE SCIENCE, 31 WATER, 4–5 RECENTLY PUBLISHED, 32–35 RECENT BEST SELLERS, 36–42 OPEN ARIZONA, 43 SALES INFORMATION, 44 CATALOG DESIGN BY LEIGH MCDONALD COVER PHOTO [FRONT] COMPOSITE BY LEIGH MCDONALD [INSIDE] BY NOSHA/FLICKR PRAISE FOR JAMES S. GRIFFITH TITLE OF THE BOOK SUBTITLE OF THE BOOK GOES HERE “Griffith recognizes the interdependence that has grown between the Tucsonese culture AUTHORand its folk NAME arts traditions.” —High Country News Keynote keynote keynote keynote keynote keynote keynote keynote Keynote keynote keynote keynote “Like a friend or relative who is eager to introduce visitors to the sights and sounds of his hometown, Griffith leads readers on a whirlwind tour celebrating Mexicano arts and crafts.” Repudant. -

Energy Storm Hits Jeju Shinhwa World

Issue 46 Jun 2018 Z Latest news from the world of amusement by ENERGY STORM HITS JEJU SHINHWA WORLD DISCOVERY’S SUCCESS ZAMPERLA RIDES SEVENTH PROJECT CONTINUES FOR WANDA GROUP WITH OCT GROUP THREE EXAMPLES OF CUSTOM DESIGNS CREATE MAJOR CHINESE GROUP ADDS POPULAR RIDE DEBUT IN 2018 UNIQUE ATTRACTIONS MORE FROM ZAMPERLA Latest news from the world of ISSUE 46 - JUNE 2018 2 amusement by Zamperla SpA Z Energy Storm hits Jeju Shinhwa World New addition joins existing Zamperla products A new customer for Zamperla in the Asia region (although previously a part of the Resort World Group) is Jeju Shinhwa World in South Korea, the theme for which is based on the experiences of the mascots of the French-South Korean computer animated TV series Oscar’s Oasis. The park first opened in the summer of 2017 and Zamperla was involved in both the first and second phases of the construction, supplying the venue with three highly themed attractions. One of these was a Magic Bikes, a popular, interactive family ride which sees participants use pedal power to make their vehicle soar into the sky. Also provided was a Disk’O Coaster, a ‘must have’ ride for every park and a best seller for Zamperla which combines thrills and speed to provide an adrenalin-filled experience. The third attraction was a Tea Cup, which incorporates triple action to create a fun and exciting experience, coupled to a high hourly capacity. And now Zamperla has also supplied an Energy Storm to the park, featuring five sweep arms which rotate upwards and flip riders upside down while also spinning. -

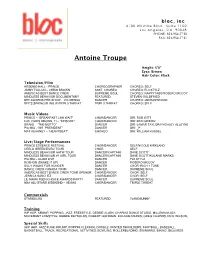

Antoine Troupe

bloc, inc. 6100 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90048 PHONE: 323-954-7730 FAX: 323-954-7731 Antoine Troupe Height: 5’8” Eyes: Brown Hair Color: Black Television/Film ARSENIO HALL - PRINCE CHOREOGRAPHER CHOREO: SELF JIMMY FALLON – CHRIS BROWN ASST. CHOREO CHOREO: FLII STYLZ AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW SUPREME SOUL CHOREO: NAPPYTABS/ROSERO MCCOY MINDLESS BEHAVIOR DOCUMENTARY FEATURED STEVEN GOLDFRIED BET AWARDS PRE-SHOW – VIC MENSA DANCER CHOREO: IAN EASTWOOD BET’S SPRING BLING W/TRIPL3 THREAT TRIPL3 THREAT CHOREO: SELF Music Videos PRINCE – “BREAKFAST CAN WAIT” CHOR/DANCER DIR: ROB WITT E40, CHRIS BROWN, TI – “EPISODE” CHOR/DANCER DIR: BEN GRIFFIN DRAKE – “THE MOTTO” DANCER DIR: LAMAR TAYLOR/HYGHLEY ALLEYNE PIA MIA - “MR. PRESIDENT” DANCER DIR: _P MAT KEARNEY – “HEARTBEAT” CHOREO DIR: WILLIAM RUSSEL Live/Stage Performances PRINCE ESSENCE FESTIVAL CHOR/DANCER SELF/NICOLE KIRKLAND CEELO GREEN EURO TOUR CHOR SELF MINDLESS BEHAVIOR AATW TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT MINDLESS BEHAVIOR #1 GIRL TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT/KOLANIE MARKS PIA MIA – GUAM LIVE DANCER FLII STYLZ ROSHON (SHAKE IT UP) DANCER ROSERO MCCOY SILLY WALKS FOR HUNGER DANCER CHOR: RICH + TONE DANCE CREW CANADA TOUR DANCER SUPREME SOUL AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW TOUR OPENER CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF JESSICA SANCHEZ CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF LIL MAMA TEEN CHOICE AWARDS PARTY DANCER SUPREME SOUL NBA ALL-STARS WEEKEND – VEGAS CHOR/DANCER TRIPLE THREAT Commercials STARBUCKS FEATURED 72ANDSUNNY Training HIP HOP, KRUMP, POPPING, JAZZ, FREESTYLE, DEBBIE ALLEN, CHAPKIS DANCE STUDIO, MILLENIUM, IDA, MOVEMENT LIFESTYLE, DEBBIE REYNOLDS, ROBERT HOFFMAN, KOLANIE MARKS, GREG CHAPKIS, NICK WILSON, Special Skills (HIP HOP, JAZZ FUNK, KRUMP, POPPIN, FLEXING), DOUBLE JOINTED SHOULDERS, FOOTBALL, BASEBALL, BASKETBALL, TRACK, RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES, BOWLING, ROLLERBLADING, SWIMMING, BIKING, BILLIARDS . -

San Diego Public Library New Additions September 2008

San Diego Public Library New Additions September 2008 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes Newspaper Room Audiovisual Materials Biographies Fiction Call # Author Title FIC/ABE Abé, Shana. The dream thief FIC/ABRAHAMS Abrahams, Peter, 1947- Delusion [SCI-FI] FIC/ADAMS Adams, Douglas, 1952- Dirk Gently's holistic detective agency FIC/ADAMSON Adamson, Gil, 1961- The outlander : a novel FIC/ADLER Adler, Elizabeth (Elizabeth A.) Meet me in Venice FIC/AHERN Ahern, Cecelia, 1981- There's no place like here FIC/ALAM Alam, Saher, 1973- The groom to have been FIC/ALEXANDER Alexander, Robert, 1952- The Romanov bride FIC/ALI Ali, Tariq. Shadows of the pomegranate tree FIC/ALLEN Allen, Preston L., 1964- All or nothing [SCI-FI] FIC/ALLSTON Allston, Aaron. Star wars : legacy of the force : betrayal [SCI-FI] FIC/ANDERSON Anderson, Kevin J. Darksaber FIC/ARCHER Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- A prisoner of birth FIC/ARCHER Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- A prisoner of birth FIC/ARCHER Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- Cat o'nine tales and other stories FIC/ASARO Asaro, Catherine. The night bird FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Emma FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Mansfield Park FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Minor works FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Northanger Abbey and Persuasion FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Sense and sensibility FIC/BAHAL Bahal, Aniruddha, 1967- Bunker 13 FIC/BALDACCI Baldacci, David. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

Curanderismo As Decolonization Therapy: the Acceptance of Mestizaje As a Remedio

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks NACCS Annual Conference Proceedings 2012: 39th Annual: NACCS@40 - Chicago, IL Mar 17th, 3:00 AM - 4:00 AM Curanderismo as Decolonization Therapy: The Acceptance of Mestizaje as a Remedio Ramon Del Castillo Metropolitan State University, [email protected] Adriann Wycoff Metropolitan State College of Denver, [email protected] Steven Cantu Metropolitan State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/naccs Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Del Castillo, Ramon; Wycoff, Adriann; and Cantu, Steven, "Curanderismo as Decolonization Therapy: The Acceptance of Mestizaje as a Remedio" (2012). NACCS Annual Conference Proceedings. 7. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/naccs/2012/Proceedings/7 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies Archive at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in NACCS Annual Conference Proceedings by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Curanderismo as Decolonization Therapy: The Acceptance of Mestizaje as a Remedio Dr. Ramon Del Castillo, Dr. Adriann Wycoff and Steven Cantu, M.A. Chicana/o Studies Department Metropolitan State College of Denver 1 March 2012 2 Abstract “Curanderismo as Decolonization Therapy: The Acceptance of Mestizaje as a Remedio” explores Chicana/o identity and its many manifestations that reflect -

Wedding Ringer -FULL SCRIPT W GREEN REVISIONS.Pdf

THE WEDDING RINGER FKA BEST MAN, Inc. / THE GOLDEN TUX by Jeremy Garelick & Jay Lavender GREEN REVISED - 10.22.13 YELLOW REVISED - 10.11.13 PINK REVISED - 10.1.13 BLUE REVISED - 9.17.13 WHITE SHOOTING SCRIPT - 8.27.13 Screen Gems Productions, Inc. 10202 W. Washington Blvd. Stage 6 Suite 4100 Culver City, CA 90232 GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 1 OVER BLACK A DIAL TONE...numbers DIALED...phone RINGING. SETH (V.O.) Hello? DOUG (V.O.) Oh hi, uh, Seth? SETH (V.O.) Yeah? DOUG (V.O.) It’s Doug. SETH (V.O.) Doug? Doug who? OPEN TIGHT ON DOUG Doug Harris... 30ish, on the slightly dweebier side of average. 1 REVEAL: INT. DOUG’S OFFICE - DAY 1 Organized clutter, stacks of paper cover the desk. Vintage posters/jerseys of Los Angeles sports legends adorn the walls- -ERIC DICKERSON, JIM PLUNKETT, KURT RAMBIS, STEVE GARVEY- DOUG You know, Doug Harris...Persian Rug Doug? SETH (OVER PHONE) Doug Harris! Of course. What’s up? DOUG (relieved) I know it’s been awhile, but I was calling because, I uh, have some good news...I’m getting married. SETH (OVER PHONE) That’s great. Congratulations. DOUG And, well, I was wondering if you might be interested in perhaps being my best man. GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 2 Dead silence. SETH (OVER PHONE) I have to be honest, Doug. This is kind of awkward. I mean, we don’t really know each other that well. DOUG Well...what about that weekend in Carlsbad Caverns? SETH (OVER PHONE) That was a ninth grade field trip, the whole class went.