History of Social Dancing at Oregon State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAC Community Services Spring 2016 Final

SANTA ANA COLLEGE COMMUNITY SERVICES PROGRAM SPRING 2016 714-564-6594 www.sac.edu/cms Take action • Aim for success • Enroll now HOW TO REGISTER On-line Registration @ www.sac.edu/cms with your MasterCard, VISA, Discover, or American Express. FAX Registration with your credit card information. Complete the registration form on the inside back cover and FAX to (714) 564-6309. Phone Registration with your MasterCard, VISA, Discover, or American Express. Call (714) 564-6594. Mail-In Registration: Complete the registration form located on the inside back cover, include payment, and mail to: Santa Ana College Community Services Program 1530 W. 17th Street, S-203 Santa Ana, CA 92706 In-Person Registration @ Community Services Program office located in the Administration Building, room S-203. See map on page 28. Confirmation: Registration received by mail will be confirmed if you send a self-addressed stamped envelope. Registration received by phone and online will automatically receive a confirmation. If you do not receive a confirmation in 5 business days, call our office at (714) 564-6594. Non-receipt of confirmation does not warrant a refund. Refund & Transfer Policy for all events: Refund and transfer requests must be made (3) business days prior to the event less a $10 processing fee per person. Day Tours: may be cancelled up to 10 days prior to departure date less a $15 processing fee. A refund will only be issued if your space can be re-sold. You may send a substitute in place. Multi Day Tours: Travel Protection insurance is highly recommended. A refund will be issued less a $50 cancellation fee. -

April 2012 Compass

The Official Magazine of Sun City Lincoln Hills April 2012 Compass Chorus to Feature “Notable” Composers ... page 13 Strategic Advisory Committee Accepting Applications ... page 2 Limited Time Special Offer on Summer Concert Series ... page 5 Planning for Additional Pickleball Courts ... page 11 Association News In This Issue Board of Directors Report Activities News & Happenings ............................. 5 SCLH: A Different Kind of Wonderland Marcia VanWagner, Director, SCLH Board of Directors Advertisers’ Directory ......................................95 Association Contacts & Hours Directory ............ 94 Alice: Which way should I go? Once we know who Board of Directors Report................................... 2 Cat: That depends on where you are going. we are, then it’s on to Bucket List........................................................ 2 Alice: I don’t know where I’m going! envisioning our future. Cat: Then it doesn’t matter which way Bulletin Board ................................................. 37 What will we need to continue our finan- you go!! Lewis Carroll,1872 cial stability? How will we market our • You Are Invited ........................................... 37 Through the Looking Glass community to maintain home values in • LH Players Announce Auditions/”O’Leary’s” ..... 37 Sun City Lincoln Hills is a different this economy? How will emerging tech- Calendar of Events ..................................... 3 kind of Wonderland from Alice’s. Your nologies affect our future? How are we Chorus to Feature “Notable” Composers ........... 13 Board of Directors is committed to using our facilities and sports venues? knowing not only where we are go- Classes ............................................................ 59 The conclusions will include recommen- ing, but also how we will get there! It dations for a lifestyle appropriate for all. Club Advertisements ................................. 6-8 became clear during our election cam- The SAC will map the route, identifying Club News .................................................... -

DVIDA American Smooth Silver Syllabus Figures

Invigilation Guidance/ DVIDA/SYLLABUS/ Current'as'of'October'15,'2015' Extracted'from: Dance$Vision$International$Dancers$Association, Syllabus$Step$List$ Revised/May/2014 Invigilation Guidance/ AMERICAN)SMOOTH) / DVIDA American Smooth Bronze Syllabus Figures *Indicates figure is not allowable in NDCA Competitions. Revised January 2014. View current NDCA List Waltz Foxtrot Tango V. Waltz Bronze I 1A. Box Step 1. Basic 1A. Straight Basic 1. Balance Steps 1B. Box with Underarm Turn 2. Promenade 1B. Curving Basic 2A. Fifth Position Breaks 2. Progressive 3A. Rock Turn to Left 2A. Promenade Turning Left 2B. Fifth Position Breaks 3A. Left Turning Box 3B. Rock Turn to Right 2B. Promenade Turning Right with Underarm Turn 3B. Right Turning Box 3. Single Corté 4. Progressive Rocks Bronze II 4A. Balance Steps 4. Sway Step 5A. Open Fan 3. Reverse Turn 4B. Balance and Box 5A. Sway Underarm Turn 5B. Open Fan with 4. Closed Twinkle 5. Simple Twinkle 5B. Promenade Underarm Turn Underarm Turn 6. Two Way Underarm Turn 6A. Zig Zag in Line 6. Running Steps 7. Face to Face – Back to Back 6B. Zig Zag Outside Partner 7. Double Corté 7. Box Step 8A. Reverse Turn Bronze III 8A. Reverse Turn 8. Twinkle 8B. Reverse Turn with 5A. Crossbody Lead 8B. Reverse Turn with 9. Promenade Twinkles Outside Swivel 5B. Crossbody Lead with Underarm Turn 10A. Turning Twinkles to 9. Right Side Fans Underarm Turn 9A. Natural Turn Outside Partner 10. Contra Rocks 6. Hand to Hand 9B. Natural Turn with 10B. Turning Twinkles to Outside 11A. Change of Places 7A. Forward Progressive Underarm Turn Partner with Underarm Turn 11B. -

The Rise of Guangchangwu in a Chinese Village

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4499–4522 1932–8036/20170005 Reading Movement in the Everyday: The Rise of Guangchangwu in a Chinese Village MAGGIE CHAO Simon Fraser University, Canada Communication University of China, China Over recent years, the practice of guangchangwu has captured the Chinese public’s attention due to its increasing popularity and ubiquity across China’s landscapes. Translated to English as “public square dancing,” guangchangwu describes the practice of group dancing in outdoor spaces among mostly middle-aged and older women. This article examines the practice in the context of guangchangwu practitioners in Heyang Village, Zhejiang Province. Complicating popular understandings of the phenomenon as a manifestation of a nostalgic yearning for Maoist collectivity, it reads guangchangwu through the lens of “jumping scale” to contextualize the practice within the evolving politics of gender in post-Mao China. In doing so, this article points to how guangchangwu can embody novel and potentially transgressive movements into different spaces from home to park, inside to outside, and across different scales from rural to urban, local to national. Keywords: square dancing, popular culture, spatial practice, scale, gender politics, China The time is 7:15 p.m., April 23, 2015, and I am sitting adjacent to a small, empty square tucked away from the main thoroughfare of a university campus in Beijing. As if on cue, Ms. Wu appears, toting a small loudspeaker on her hip.1 She sets it down on the stairs, surveying the scene before her: a small flat space, wedged in between a number of buildings, surrounded by some trees, evidence of a meager attempt at beautifying the area. -

The History of Square Dance

The History of Square Dance Swing your partner and do-si-do—November 29 is Square Dance Day in the United States. Didn’t know this folksy form of entertainment had a holiday all its own? Then it’s probably time you learned a few things about square dancing, a tradition that blossomed in the United States but has roots that stretch back to 15th-century Europe. Square dance aficionados trace the activity back to several European ancestors. In England around 1600, teams of six trained performers—all male, for propriety’s sake, and wearing bells for extra oomph—began presenting choreographed sequences known as the morris dance. This fad is thought to have inspired English country dance, in which couples lined up on village greens to practice weaving, circling and swinging moves reminiscent of modern-day square dancing. Over on the continent, meanwhile, 18th- century French couples were arranging themselves in squares for social dances such as the quadrille and the cotillion. Folk dances in Scotland, Scandinavia and Spain are also thought to have influenced square dancing. When Europeans began settling England’s 13 North American colonies, they brought both folk and popular dance traditions with them. French dancing styles in particular came into favor in the years following the American Revolution, when many former colonists snubbed all things British. A number of the terms used in modern square dancing come from France, including “promenade,” “allemande” and the indispensable “do-si-do”—a corruption of “dos-à-dos,” meaning “back-to-back.” As the United States grew and diversified, new generations stopped practicing the social dances their grandparents had enjoyed across the Atlantic. -

Be Square Caller’S Handbook

TAble of Contents Introduction p. 3 Caller’s Workshops and Weekends p. 4 Resources: Articles, Videos, etc p. 5 Bill Martin’s Teaching Tips p. 6 How to Start a Scene p. 8 American Set Dance Timeline of Trends p. 10 What to Call It p. 12 Where People Dance(d) p. 12 A Way to Begin an Evening p. 13 How to Choreograph an Evening (Programming) p. 14 Politics of Square Dance p. 15 Non-White Past, Present, Future p. 17 Squeer Danz p. 19 Patriarchy p. 20 Debby’s Downers p. 21 City Dance p. 22 Traveling, Money, & Venues p. 23 Old Time Music and Working with Bands p. 25 Square Dance Types and Terminology p. 26 Small Sets p. 27 Break Figures p. 42 Introduction Welcome to the Dare To Be Square Caller’s handbook. You may be curious about starting or resuscitating social music and dance culture in your area. Read this to gain some context about different types of square dancing, bits of history, and some ideas for it’s future. The main purpose of the book is to show basic figures, calling techniques, and dance event organizing tips to begin or further your journey as a caller. You may not be particularly interested in calling, you might just want to play dance music or dance more regularly. The hard truth is that if you want trad squares in your area, with few ex- ceptions, someone will have to learn to call. There are few active callers and even fewer surviving or revival square dances out there. -

San Diego Dance Programs Available at Dance Motion Studios

San Diego Dance Programs Available at Dance Motion Studios Dance Styles Ballroom Dances Classic and elegant, Ballroom Dance is a timeless and beautiful art form, but don't expect this genre to stop at the Waltz. Try the passionate heat of the Tango, or the energetic Foxtrot. You¶ll be surprised at the range and variety of ballroom dances to suit any taste or style. Our accomplished ballroom dance instructors are experienced in teaching dancers of all ability levels. y Quickstep y Tango y Viennese Waltz y Waltz Latin Dances Free-spirited and sensual, Latin dances are fun and a great way to learn how to dance. Due to their passionate movements and intoxicating rhythms, these Latin American imports have a dedicated following. Make your way through our extensive range of Latin dance programs and discover your Latin flair. y Bolero y Cha-Cha y Jive y Mambo y Rumba y Samba Social Dances We offer a number of dance styles perfectly suited for dance clubs and parties. Develop the ability to spin and dip your partner with ease, or find the confidence to step onto the dance floor and move your body with poise and grace. Whatever your skill level and goals, we have programs suited for your needs and instructors who will help you develop into the social dancer you¶ve always wanted to be. y Argentine Tango y East Coast Swing y Hustle y Lindy Hop y Merengue y Nightclub Two-step y Salsa y West Coast Swing Private Lessons Private lessons are ABSOLUTELY the most effective and efficient way to learn ballroom dancing. -

Kickish: the Language of Line Dance

ILDSF KICKISH: THE LANGUAGE OF LINE DANCE A VOCABULARY AND FORMAT FOR STANDARDIZED LINE DANCE STEP SHEETS 4256 N. SVENSK LANE EAGAN, MN 55123 A VOCABULARY FOR LINE DANCERS Let's say you are a line dancer who is writing or reading line dance choreography. A. You have choreographed the perfect dance. It fits the music and your personality. It is interesting, creative, and a sure-fire hit. Now you want to write a clear description of the dance, which we call a step sheet. B. Perhaps English is not your native language, and you want to write a step sheet in English that makes sense to English-speaking people, without errors from computer-based translations. C. Perhaps you wonder why some step sheets are easier to read than others. You notice one portion of a step sheet is easy to read, while another portion of the same step sheet is unclear. Why does that happen? In this article we examine a few aspects of step sheets that affect readers' ability to understand what is written, and we will describe a small line dance language (vocabulary and format) that can be used for nearly all line dances ever written (so far). After looking over a list of language names like Spanish, Danish, Polish, Elvish, etc., and bearing in mind that this language is used extensively in the line dance archive at the Kickit website, we have decided to call this language Kickish: The Language of Line Dance. WHAT MAKES A STEP SH EET READABLE? Just as a sculpture, river, or person cannot be fully described in text, a step sheet can never fully describe a dance. -

Danc-Dance (Danc) 1

DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 DANC 1131. Introduction to Ballroom Dance DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 Credit (1) Introduction to ballroom dance for non dance majors. Students will learn DANC 1110G. Dance Appreciation basic ballroom technique and partnering work. May be repeated up to 2 3 Credits (3) credits. Restricted to Las Cruces campus only. This course introduces the student to the diverse elements that make up Learning Outcomes the world of dance, including a broad historic overview,roles of the dancer, 1. learn to dance Figures 1-7 in 3 American Style Ballroom dances choreographer and audience, and the evolution of the major genres. 2. develop rhythmic accuracy in movement Students will learn the fundamentals of dance technique, dance history, 3. develop the skills to adapt to a variety of dance partners and a variety of dance aesthetics. Restricted to: Main campus only. Learning Outcomes 4. develop adequate social and recreational dance skills 1. Explain a range of ideas about the place of dance in our society. 5. develop proper carriage, poise, and grace that pertain to Ballroom 2. Identify and apply critical analysis while looking at significant dance dance works in a range of styles. 6. learn to recognize Ballroom music and its application for the 3. Identify dance as an aesthetic and social practice and compare/ appropriate dances contrast dances across a range of historical periods and locations. 7. understand different possibilities for dance variations and their 4. Recognize dance as an embodied historical and cultural artifact, as applications to a variety of Ballroom dances well as a mode of nonverbal expression, within the human experience 8. -

By Barb Berggoetz Photography by Shannon Zahnle

Mary Hoedeman Caniaris and Tom Slater swing dance at a Panache Dance showcase. Photo by Annalese Poorman dAN e ero aNCE BY Barb Berggoetz PHOTOGRAPHY BY Shannon Zahnle The verve and exhilaration of dance attracts the fear of putting yourself out there, says people of all ages, as does the sense of Barbara Leininger, owner of Bloomington’s community, the sheer pleasure of moving to Arthur Murray Dance Studio. “That very first music, and the physical closeness. In the step of coming into the studio is sometimes a process, people learn more about themselves, frightening thing.” break down inhibitions, stimulate their Leininger has witnessed what learning to minds, and find new friends. dance can do for a bashful teenager; for a man This is what dance in Bloomington is who thinks he has two left feet; for empty all about. nesters searching for a new adventure. It is not about becoming Ginger Rogers or “It can change relationships,” she says. “It Fred Astaire. can help people overcome shyness and give “It’s getting out and enjoying dancing and people a new lease on life. People get healthier having a good time,” says Thuy Bogart, who physically, mentally, and emotionally. And teaches Argentine tango. “That’s so much they have a skill they can go out and have fun more important for us.” with and use for the rest of their lives.” The benefits of dancing on an individual level can be life altering — if you can get past 100 Bloom | April/May 2015 | magbloom.com magbloom.com | April/May 2015 | Bloom 101 Ballroom dancing “It’s really important to keep busy and keep the gears going,” says Meredith. -

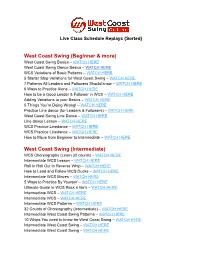

West Coast Swing (Beginner & More)

Live Class Schedule Replays {Sorted} West Coast Swing (Beginner & more) West Coast Swing Basics – W ATCH HERE West Coast Swing Dance Basics – W ATCH HERE WCS Variations of Basic Patterns – W ATCH HERE 5 Starter Step Variations for West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE 7 Patterns All Leaders and Followers Should know – W ATCH HERE 5 Ways to Practice Alone – WATCH HERE How to be a Good Leader & Follower in WCS – WATCH HERE Adding Variations to your Basics – W ATCH HERE 5 Things You’re Doing Wrong! – WATCH HERE Practice Line dance (for Leaders & Followers) – W ATCH HERE West Coast Swing Line Dance – WATCH HERE Line dance Lesson – W ATCH HERE WCS Practice Linedance – W ATCH HERE WCS Practice Linedance – W ATCH HERE How to Move from Beginner to Intermediate – WATCH HERE West Coast Swing (Intermediate) WCS Choreography (Learn 32 counts) – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Lesson – WATCH HERE Roll In Roll Out to Reverse Whip – WATCH HERE How to Lead and Follow WCS Ducks – W ATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Moves – WATCH HERE 5 Ways to Practice By Yourself – WATCH HERE Ultimate Guide to WCS Rock n Go’s – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Patterns – WATCH HERE 32 Counts of Choreography (Intermediate) – W ATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing Patterns – WATCH HERE 10 Whips You need to know for West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE West Coast Swing ( Advanced) Advanced WCS Moves – WATCH HERE -

The Thought on Square Dancing Heat in China

Frontiers in Art Research ISSN 2618-1568 Vol. 2, Issue 2: 28-32, DOI: 10.25236/FAR.2020.020208 The Thought on Square Dancing Heat in China Xia Li1, 2 1 School of Management, Shinawatra University, Bangkok 12160, Thailand 2 School of Engineering and Design, Hunan Normal University, Changsha 410081, China ABSTRACT. According to statistics, in 2017, there were about 100 million square dance enthusiasts in China. With the continuous development of the national fitness heat, square dance has become a social and cultural phenomenon and is becoming increasingly popular. It is loved by the majority of the elderly and spreads rapidly. The development of square dance is closely related to the social environment and cultural needs. It not only is beneficial to the physical fitness and entertainment, but also has a deeper meaning in maintaining social harmony and stability and improving the aesthetics of the entire people. This article attempts to elaborate on the square dance risen in the past ten years, and analyzes it from four levels, namely national policy support, the artistic feature of square dance, the impact on the physical and mental health of the elderly, and the impact on society. The author also gives advice on the current situation of square dance, and makes predictions to the development and changes of square dance. KEYWORDS: Square dance; Artistic feature; The elder dance 1. Introduction With the development of Chinese society, the government has given more space for the development of folk and community art activities, and the demand for cultural life has increased. Against this background, square dance has emerged as the times require, and the problems caused by the imperfect management of square dance are also emerging too.